Lael Morgan

- 1972

Fellowship Title:

- Alaskan Eskimos, Aleuts and Indians in Transition

Fellowship Year:

- 1972

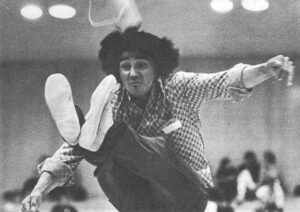

Eskimo Olympics

Fairbanks, Alaska August 9, 1972 A crowd of 1,500 watches silently. The air is hot and tacky, heavy with the strain of concentration. Reggie Joule, a young Alaskan Eskimo from Kotzebue, studies the high kick target which dangles almost two feet above his head. Twice he has failed to kick it in a style acceptable to the judges. If he fails again he is sure the Eskimo Olympic title will go to a Canadian. Watching quietly nearby is Mickey Gordon, a 27-year-old athlete from the raw tundra of Inuvik on the MacKenzie River Delta. Back in Canada he holds the high kick record. He has jumped against Joule before and won. But something has happened to the Alaskan in the five months since the competed at the Canadian Winter Games. His style is better. He has knocked off some awkward edges. Joule springs with bullet-like speed, feet above his head, sends the target flying and makes a balanced landing. The judges shake their heads. His two feet did not hit the floor at the

The Tyonek Indian Tycoons Learning the Hard Way

Tyonek, Alaska August 4, 1972 In 1963 the Tyonek Indians, an impoverished, tribe of 200 Athabascans on the shores of Alaska’s Cook Inlet, collected a windfall of $11,671,675. in oil lease revenues. Despite the fact that few among them had much formal education and their individual incomes had previously averaged at best about $1,000 per annum, the Tyoneks fought vigorously for release from the stewardship of the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the right to manage their own future. They won, laid a careful foundation for preservation of their prosperity and were soon being hailed by Time, Life Magazine and the Wall Street Journal as the “Tyonek tycoons.” They built a modern village to replace the random sampling of shacks and tattered log cabins they had previously called home. They established an impressive education program for any Tyonek who expressed interest in self-improvement. They loaned $100,000 to the Alaska Federation of Natives, without which the state’s Indians and Eskimos could probably not have fought for and won their billion dollar federal land claims settlement.

Indian Artists Versus Artists Who Are Indians

Anchorage, Alaska July 17, 1972 For well over two centuries the artistic accomplishment of the Indians of the Pacific Northwest Coast has astonished all who have experienced it. Russians, Englishmen, Frenchmen, Spaniards and Yankee merchant mariners visited Alaska and the adjacent coastal islands to explore and trade among these unusual people. All of the visitors who were sufficiently literate to record their experience registered also their intellectual and emotional responses to the all-prevading creative production of this unique coastal culture…. The white man discovered Alaska and the coast at a period when the culture of the Indian flourished. He watched it come to full flower, and in his way, plucked the seed to see the culture diminish. Today the art expressions of the culture are scattered over the world and only in recent years have become desirable items for art collectors and museums of art. Through the process of acculturation, the vigor of the native is being redirected. During this period of transition the emotional and personal stimuli to continue the traditional arts have died.

Tundra Times: A Survival Story

Photos by Frank Murphy Fairbanks, Alaska July 15, 1972 One of the most astonishing survival stories of the Far North is that of the Tundra Times. This fall the little Eskimo-Indian newspaper celebrates its 10th year of publication, flourishing in the financial wasteland of the Arctic on an erratic circulation that wavers between 1,500 and 5,000. More remarkable is the influence exerted by this hardy weekly and its Eskimo editor, Howard Rock. Working with one reporter, or often just a part-time staffer, Rock has shaken high offices in Washington, D.C., with the force of seismic seizure and helped change the face of Alaska. Perhaps more than anyone else, he helped weld together the frontier state’s 55,000 natives for their successful, years-long fight to win the largest aboriginal land-claims settlement in American history,” notes Stanton H. Patty, veteran Alaskan observer for the Seattle Times. “He was their voice, at times about the only calm voice when crescendos of invective threatened to tear Alaska apart.” Howard Rock – Eskimo editor of the Tundra Times,

Galena – How To Win A Flood?

Galena, Alaska June 27, 1972 Today the Athabascan Indian village of Galena is the goingest, growingest village on the Yukon. Its residents enjoy a unique prosperity gained through plentiful fishing and hunting and high employment opportunity. The future looks brighter still, and it’s hard to believe that just a year ago Galena nearly came off the map. In the spring of 1971 the thawing Yukon River ran wild. Below Galena it jammed, backed up and rushed its banks, inundating the little settlement with 13 feet of water and smashing blocks of ice. A neighboring Air Force Base sat low but dry behind a 136 foot dike that excludes the village. The commander, unsure of the holding power of his World War II vintage earth rampart, evacuated 266 servicemen and any villagers who wanted to go. The majority of Indians declined. They knew from past experience that evacuation can be a one way trip. Someone usually turns up to rescue imperiled natives but sometimes evacuees without resources are left to find their own way home.