Michael Hudson

- 1992

Fellowship Title:

- Business That Target Low-Income Americans

Fellowship Year:

- 1992

Fringe Banking

Banks don’t want her business. So when Pacquin Davis needed to cash her welfare check one recent Tuesday evening, she went to the Shopper’s Market around the corner from her apartment in an Atlanta public housing complex. The grocer charged her $3 to cash the $390 check. Davis pays her rent with money orders. They usually cost 69 or 75 cents. When she needs a small loan around Christmastime, she pawns her air conditioner at Fulton Loan Office. The pawn shop charges interest of 20 percent a month on its loans — which equals an annual rate of 240 percent. Davis and her five children — like an estimated 20 million families — are part of America’s growing non-bank economy. Thousands of new pawn shops and check-cashing outlets — sometimes called “fringe banks” by economists — have sprung up across the country to serve them. Since 1987, the number of check-cashing outlets has jumped from about 2,000 to about 5,000 — a figure that doesn’t include the thousands of inner city grocers, liquor stores and

The Costly “Banks” That Welcome The Poor

Ask Jack Daugherty how many pawn shops he owns in the United States, and he has to put down the phone for a minute to check. “It’s kinda a moving target,” he apologizes. “I have to ask somebody every week.” The correct answer: 225. For now, at least. A decade ago Daugherty owned just one, in Irving, Texas. But in 1983, after years as an absentee owner dabbling in night clubs and dry oil wells, Daugherty had an idea. His pawn shop was surpassing more established competitors. He thought the reason was a simple ethic of customer service: Give ’em self-esteem. Make sure things look nice and the employees are friendly and fair, so people won’t have to feel like they have to slink into a pawn shop. Daugherty turned that idea into an empire of Cash America pawn shops that stretches across the Southeast and into Ohio and Colorado-and has designs on every state in the union. Cash America is one of a new breed of businesses that has sprung up on urban street

“Rent-to-Own”: The Slick Cousin of Paying on Time

Some people call Larry Sutton “The Reverend of Rent To-Own.” Sutton preaches the blessings of the rent-to-own business with the enthusiasm of a true believer. He owns a growing number of Champion Rent-to-own stores in Florida and Georgia: more than 20 so far. They offer televisions, stereos, furniture, washers, you name it, at weekly or monthly rates. If they pay long enough, customers can someday own these things. If they can’t, the store picks the merchandise up and rents it to someone else. Sutton likes to think of renting-to-own as something like a marriage, with the same mutual debts and duties. The hardest part of the relationship, Sutton once told a seminar of rental dealers, is getting money from customers who are squeezing by from one paycheck or welfare grant to the next. “I had one guy tell me the best close he ever used was: ‘If you don’t pay, the s- – – don’t stay.’” Sutton frowns on that approach. Rent-to-own stores have a duty to take care of their customers. “More than anything

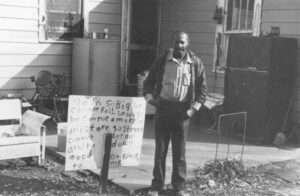

Loan Scams

Some days it seems like the phone at Annie Ruth Bennett’s house in southwest Atlanta won’t ever stop ringing. The callers want to sell her storm windows, debt–consolidation loans, burial plots. Her attorney says it’s all a scheme: They want to steal a piece of her home by getting her to take out a loan against its value. But now she knows better. She and her husband Frank, 73, are already struggling to pay $469 a month of their tiny incomes to pay off a loan from Fleet Finance, a giant national mortgage company. The Bennetts say they took out the loan after a home repair contractor knocked on their door and offered to fix up their small frame house. He arranged an 18.5-percent second mortgage. Then he took nearly $10,000 to pay himself for work that an appraiser later valued at $1,245. James Hogan’s problems started in 1989 when he borrowed and then paid $6,200 to a home-repair contractor in Atlanta to fix his roof and do other work. His attorney says an independent