Some people call Larry Sutton “The Reverend of Rent To-Own.”

Sutton preaches the blessings of the rent-to-own business with the enthusiasm of a true believer.

He owns a growing number of Champion Rent-to-own stores in Florida and Georgia: more than 20 so far. They offer televisions, stereos, furniture, washers, you name it, at weekly or monthly rates. If they pay long enough, customers can someday own these things. If they can’t, the store picks the merchandise up and rents it to someone else.

Sutton likes to think of renting-to-own as something like a marriage, with the same mutual debts and duties. The hardest part of the relationship, Sutton once told a seminar of rental dealers, is getting money from customers who are squeezing by from one paycheck or welfare grant to the next. “I had one guy tell me the best close he ever used was: ‘If you don’t pay, the s- – – don’t stay.'”

Sutton frowns on that approach. Rent-to-own stores have a duty to take care of their customers. “More than anything else,” he said, “they are paying us to manage their money.”

Advocates for the poor don’t see rent-to-own quite so benevolently. They say the industry’s phenomenal growth in the past decade has come by exploiting low-income people who have few choices and little political clout. According to the industry’s own figures, only about one-fourth of its customers achieve their goal of ownership.

Rent-to-own customers routinely pay two, three, and four times what merchandise would cost if they could afford to pay cash. For example: A Rent-A-Center store in Roanoke, Virginia, recently offered a 20-inch Zenith TV for $14.99 a week for 74 weeks-or $1,109.26. Across town at Sears, the same TV was on sale for $329.99. Putting aside $15 a week, it would take just 22 weeks to save enough to buy it retail.

Iris Green has lived for 20 years in public housing in Paterson, N.J. She has no car and has never shopped outside Paterson. She paid Continental Rentals nearly $4,000 toward the purchase of a stereo, a freezer, a washer and other furnishings that had a cash price of less than $2,800. Then she got sick and the paychecks from her job as a nursing home aide stopped coming. She fell behind, and Continental came and took everything. Now she’s suing the company.

“My opinion, I thought they was my friends,” Green said. I felt betrayed. I felt disgusted. I felt lonely. “She told her sons to stop bringing their girlfriends over, ‘They had nowhere to sit.’”

Rent-to-own is an example of an age-old principle that has gained new attention since the inner city uprisings in Los Angeles and other places: The poor pay more. They pay more for groceries, loans, second mortgages, check cashing and consumer goods. The businesses that do operate in poor areas say they must charge more because of credit risks and theft.

Continental Rentals and other rent-to-own dealers say they offer fair prices and exceptional service to consumers who otherwise couldn’t afford to own quality appliances or furniture.

From a business standpoint, the rent-to-own industry has been a success story of the past decade, growing from about 2,000 stores nationwide in 1982 to about 7,000 now. Estimated revenues climbed from $2 billion in 1988 to $3.6 billion in 1991.

“How can we do that by ripping off our customers?” asks Bill Keese, who directs the industry’s national trade association, “The rapid growth proves the industry treats its customers fairly”, he said.

The industry’s rise is a story of demographics and salesmanship-and lawsuits and lobbying. Legal Aid lawyers who represent the poor have fought to rein in rent-to-own, but the industry has succeeded in getting laws passed in 30 states that protect it from most legal attacks.

Rent-to-own has prospered in the marketplace by targeting the bottom third of the economic ladder. “Most of our customers are the throwbacks from the retailers that will not deal with them,” Continental Rentals owner Michael Schecter said in a court deposition. They have limited incomes and they simply can’t save money.

The industry got its start during the 1960s. State and federal governments were passing laws to control ghetto merchants who used retail installment contracts to fleece poor people. The rent-to-own industry was born during this time “as a result of the tightening of consumer credit and burgeoning federal consumer protection legislation,” its trade group, the Association of Progressive Rental Organizations says.

Rent-to-own and retail credit are essentially the same transaction: selling merchandise on time. But rent-to-own dealers have generally managed to escape state and federal credit laws because of one difference: Rent-to-own customers can bring their merchandise back any time with no obligation for the rest of the payments.

The added cost of buying on time from a traditional retailer-the difference between the cash price and the total installment price-is a finance charge regulated by state usury laws. In New,Jersey, for example, retailers can charge no more than 30 percent interest each year.

Rent-to-own dealers say they are exempt front usury laws because they do not charge interest. They say the extra price Of buying on time from them is a service charge covering their higher costs of doing business, such as making free repairs.

Avoiding retail credit limits has allowed rental dealers to charge much higher prices than retailers. Rent-to-own customers often pay markups that are equal to interest rates of 100 to 200 percent a year. A survey by the New Jersey Public Advocate, a state agency, turned tip a store that was selling a microwave with a markup equal to 440 percent interest.

Such price advantages helped rent-to-own grow steadily in the 1970s and then boom during the uninhibited capitalism of the 1980s, when the industry produced many millionaires and prompted corporate buyouts. In 1987, Thorn EMI, a British conglomerate that owned half the United Kingdom’s rental market, purchased the Wichita based Rent-A-Center chain for $594 million. The American company now has more than 1,200 stores nationwide. It claims, along with its, parent, to be the largest buyer of consumer electronics in the world.

Industry officials say the bulk of their customers are working-class families and, increasingly, soldiers and professionals who move front town to town and want only short-term rentals. “The term rent-to-own, in a nutshell, is a marketing concept more than a description of the business,” Champion’s Sutton said in an interview.

Still, among themselves at least, rent-to-own dealers concede that in any of their customers usually struggle to get by.

Sutton told dealers at one how-to seminar that rent to-own stores should try to work with slow paying customers but you can’t run a business by letting them get too far behind. You’ve got to get four payments every month, he advised dealers.

“We can be good friendly Joes and we can work with ‘em till heck freezes over,” Sutton said. “But I tell you what, if we’re getting three-for-four, sooner or later you’ll be out of business. Trust me.”

Getting four-for-four takes nurturing, just like a good marriage, he said. You’ve got to make repairs when the customer asks and keep all your other promises.

“You’ve got to somehow convince him that you’re different than all the rest,” Sutton said. “Because John’s Finance Company called him about money. Fred from the car company called him about money. Jackson Brown from the, clothing store called him about money. You don’t want money. You’ve just got to get an agreement renewed.”

Debra Dillard has a great relationship with the manager at the Prime Time Rentals near tier home in Trenton, N.J. She’s even become his son’s godmother. Dillard, who runs a day-care business in her home, could shop elsewhere. But she prefers Prime Time’s friendliness and convenience. “I pick up the phone. If I have a problem, they’re there. It’s solved, whether it’s a repair or replacement, or I forget how to program my VCR.”

She likes the idea of not getting stuck in contracts she can’t escape. Also, she doesn’t have to lay things away or come tip with a big down payment. “That makes it easier for you to have the things you want in life.”

Other customers have fewer choices. Dee Burnett is raising five children and grandchildren on welfare and food stamps in Roanoke, Va. For more than a year, she has been paying, $220 a month to Magic Rentals for a freezer, refrigerator, stove and bunk beds. Burnett knows she paying more than she would retail, but her divorce left tier broke and ruined her credit. Once she pays Magic off, she says, she’ll never go back. “From now on, if there’s something I want, I don’t need it right away. I’ll lay it away and pay when I can.”

In New Jersey, the Consumers League Education Fund has produced an anti-rent-to-own rap song that’s getting some radio airplay as a public-service announcement: “With rent-to-own, your money’s blown/You keep on paying till you turn to stone. “

Critics say high prices are only part of the problem. Legal Aid lawyers charge that some unscrupulous dealers sell used goods as new, break into people’s homes to repossess merchandise, charge exorbitant insurance and late fees, and use the threat of criminal charges to intimidate late-paying customers. A West Virginia rent-to-own company recently settled lawsuits by four customers who had been jailed on theft charges that were filed by the dealer but later thrown out of court. In Minnesota, Legal Aid lawyers have accused Rent-A-Center stores of usury and racketeering in a class-action lawsuit involving 10,000 or more customers.

Still, the industry has beaten back most lawsuits-either by winning favorable court rulings or by silencing unhappy Customers with confidential cash settlements. This March, in Minnesota, the industry defeated its toughest legal challenge to date: a class-action lawsuit filed by Legal Aid and private attorney’s charging Rent A-Center with usury and racketeering against more than 10,000 customers. A legal team from Shook, Hardy & Bacon-a Kansas City firm known for its invincibility as a defender of tobacco companies-convinced a federal jury that rent-to-own transactions are not covered under Minnesota’s retail credit act.The jury took just 90 minutes to return with a verdict for Rent-A-Center.

At the same time they’ve been winning in court, rent-to-own dealers have sideswiped their opponents with an effective legislative strategy: pushing through industry-written laws that provide some state regulation but allow dealers to avoid retail credit limits.

These laws require dealers to reveal basic information such as the total cost of an item and whether it is used. But critics say such laws allow rental dealers to continue charging outrageous prices. “Disclose and anything goes,” some Legal Aid attorneys call it.

The industry’s trade association has pushed its agenda with well-financed lobbying.

In North Carolina, state Rep. Jeanne Fenner proposed a law in 1983 that would have treated rent-to-own deals like retail sales. The bill eventually was gutted, but the industry took revenge when Fenner came up for reelection two years, later. Rent to-own dealers as far away as Texas gave more, than $6,000 to her Republican challenger-accounting for half of his campaign donations. Fenner, who spent $2,000, lost the election. When she ran for the state senate the next year, the industry gave her opponent $15,000. Fenner lost again.

Since then, attempts to regulate rent-to-own prices in North Carolina have failed.

Thirty states have passed laws that require price disclosures but give the industry safe harbor from retail credit regulations. In five of those states, consumer activists managed to win sonic limits on the total markup that rent-to-own dealers can charge. In Connecticut, for example, the limit is twice the cash price.

The industry has lost outright in only one state. Pennsylvania passed a law in 1989 that defines rent-to-own deals as retail sales and sets an interest limit of 18 percent a year. Pennsylvania’s rent-to-own dealers claimed the new law would put them out of business, but many found a way to skirt it. They offer straight rentals-with the promise of a rebate that the customer call use to purchase the item at the end of tile contract.

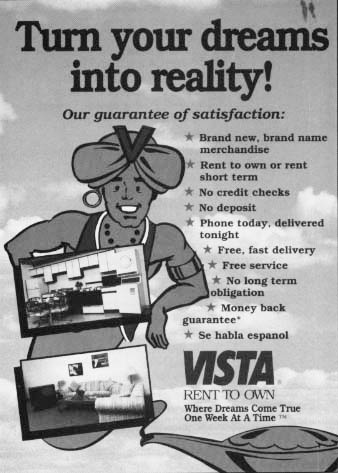

Nationally, rental dealers are pushing Congress to pass a national version of the industry-written state laws. Their trade association also is planning a public-relations campaign that pushes rent-to-own as “an alternative way to get a piece of the American Dream.”

Many dealers are diversifying their product lines, offering jewelry and even automobiles. Sutton’s Champion stores have been heading upscale, offering personal computers, fax machines and beeper’s.

All that’s fine for business, Sutton says, but you won’t make money if all you’re doing is peddling merchandise to a faceless public.

In August, at a seminar in New Orleans for fellow dealer, Sutton told a story about one of his store managers, a country boy with little education who also happens to be Sutton’s top money maker.

One day, a customer tried to turn in his portable TV and VCR. He had decided to get something from the Rent-A-Center down the street. The manager, who’d gone out of his way in the past to help the customer, blew up.

He ordered the customer to take his, TV and VCR home, and pay his back payments right away.

“Now, two more things”, the manager said. “One: Don’t never, ever let me catch you taking that TV and VCR out of your room again. No. 2: Don’t ever let me hear about you going into Rent A Center store again. You got it?”

The customer meekly apologized for momentarily straying.

Sutton wouldn’t recommend teaching store managers to jump up and down like jealous boyfriends. But he said his manager did teach him an important lesson about dealing with people: “He doesn’t rent televisions. He doesn’t rent washers. He doesn’t sell anything. He develops relationships with people.”

©1993 Michael Hudson

Michael Hudson, on leave from the Roanoke Times & World News, is investigating businesses that target low-income Americans.