Roger Clawson

- 1989

Fellowship Title:

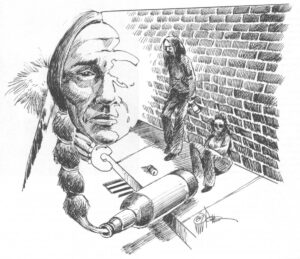

- Alcohol Abuse by Indians

Fellowship Year:

- 1989

The Alarming Increase in Alcohol-Damaged Children

Malvina is a million dollar baby. Malvina has fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS). Her mother, a young Indian woman from Alaska who drank heavily while angrily denying her pregnancy, sought medical assistance only after the first labor pains signaled Malvina’s imminent arrival. During her time in the womb, Malvina wallowed in alcohol as often as her mother drank. The placenta allowed free passage of alcohol consumed by the woman into the baby’s bloodstream. Her mother left the hospital and was back on Skid Row while Malvina’s medical bills soared past $100,000. Just ten years ago, most low birth weight babies with severe problems died at birth. Today newborn intensive care saves four of five. When doctors deem her strong enough, Malvina will need surgery for cleft palate at a cost of $75,000. If she survives, she can look forward to almost certain rehospitalization for pneumonia, failure to thrive, hip dysplasia and other problems at a cost of $15,000. Heart, dental, kidney and spinal problems may appear later. In addition to foster care, Malvina will need a

Beating Alcohol Through Tribal Self-Help

A giant of an Indian knocked at a door in Custer, Montana on a sultry afternoon in the late 1940s. The big man wore three braids under a flat-brimmed, dome-crowned hat. He asked for my father and Dad joined him on the front lawn where they sat cross-legged, smoked and talked the sun down. When it was safely dark, my father drove downtown to buy whiskey. Bootlegging suffered but did not die in 1953 when Congress repealed statutes prohibiting sale of liquor to native Americans, ending an era of prohibition that began in 1645 when the Connecticut Colony outlawed sale of alcohol to local tribes. Newspaper articles from 1953 mention civil rights, but some Indians saw lifting of the ban as yet another white assault on their people. Many agreed with an elderly Crow woman who said, “They’re just trying to kill more Indians.” On August 16, the first day of the new era, Crow and Cheyenne men loitered in the morning sun along Hardin, Montana’s Center Street, waiting for a bar to open. At

Death By Drink: The Sad Battle of America’s Indians

Vernon Kills On Top’s new home is his sanctuary. Within the quiet refuge of death row at Montana State Prison he will outlive many of his friends. “This is a safe place,” Kills On Top said recently. “My friends are out there dying.” Kills On Top and his brother, Lester, await execution for the murder of John “Marty” Etchemendy, a white man from a white community. Appeals are expected to consume the next 10 years. While the brothers wait in the safety of their cells, alcohol, the leading killer in Indian country, stalks their friends. “They’ll die in car wrecks and alley fights. Some will kill themselves and others will kill their livers. Alcohol will get them all,” Vernon Kills On Top said. Alcohol is no stranger to the Kills On Top brothers, either, and found them early. “When I was five, my parents put me to sleep with booze so they could go out drinking,” Lester remembers. Now together on death row, these Cheyenne brothers spent most of their lives apart. Lester was shuffled