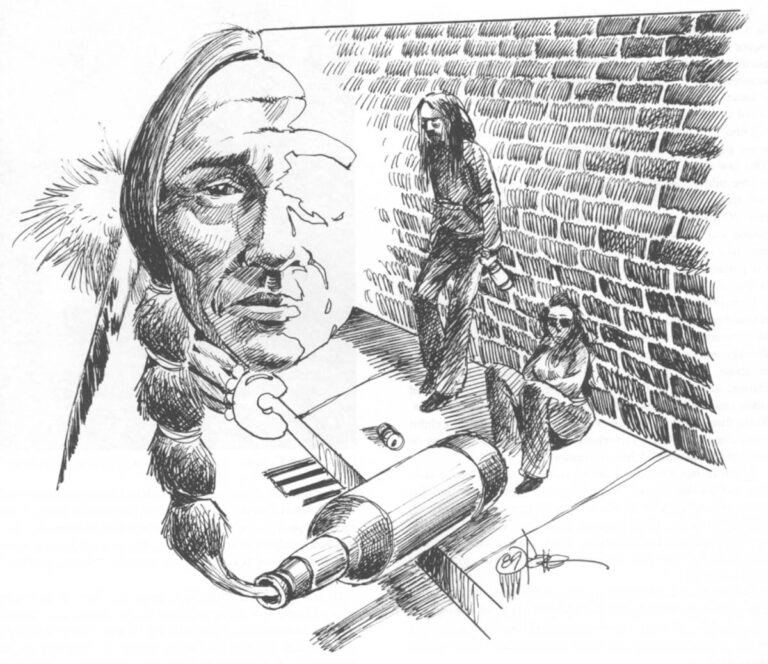

Vernon Kills On Top’s new home is his sanctuary. Within the quiet refuge of death row at Montana State Prison he will outlive many of his friends.

“This is a safe place,” Kills On Top said recently. “My friends are out there dying.”

Kills On Top and his brother, Lester, await execution for the murder of John “Marty” Etchemendy, a white man from a white community. Appeals are expected to consume the next 10 years.

While the brothers wait in the safety of their cells, alcohol, the leading killer in Indian country, stalks their friends. “They’ll die in car wrecks and alley fights. Some will kill themselves and others will kill their livers. Alcohol will get them all,” Vernon Kills On Top said.

Alcohol is no stranger to the Kills On Top brothers, either, and found them early. “When I was five, my parents put me to sleep with booze so they could go out drinking,” Lester remembers.

Now together on death row, these Cheyenne brothers spent most of their lives apart. Lester was shuffled from one home to another until he assaulted his foster father and battered two white students.

Alcohol is a unifying factor among many imprisoned Indian men.

Peter Sand Crane Jr., another Cheyenne, has returned to the safety of Montana State Prison. Sand Crane was first exposed to alcohol in the womb. His mother drank heavily while carrying him. Because the placenta is transparent to alcohol, he wallowed in alcohol in the womb months before birth. “I think my mother wanted to kill me,” Sand Crane said. “I was born an alcoholic.”

Alcohol would orphan Sand Crane before he was 13. His father shot himself after a long drinking bout and his mother was too drunk to walk when she froze to death outside her home.

Sand Crane first clashed with the law when he was five. “I was jailed for sniffing glue,” he said. In the absence of de-tox centers, anyone found intoxicated, even children, is likely to be jailed. Stealing, drinking and fighting, he was trouble off and on until he was sent to prison for slashing a man in a drunken brawl. The wound was not life threatening, but Sand Crane served 12 years. Montana’s Board of Pardons did not consider him a good risk for parole.

The board was right. Discharged at the end of his term, Sand Crane hit the street with $200 and itches to be scratched. Less than 48 hours and a large quantity of beer, whiskey, pot and speed later, Sand Crane was arrested in Billings for the brutal death of a Crow woman, Alfredine Old Crane.

In the violent milieu of Indian alcohol abuse it is sometimes difficult to sort the victims from the perpetrators. Alfredine met Sand Crane on a drinking binge that began when she read in the newspaper that her son had died. The child was born with Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS), a complex of birth defects caused by drinking during pregnancy. In foster care since his birth, the youngster was not expected to live, but no one told Alfredine her 3-year-old had died.

Alfredine died within a few blocks of the Billings parking garage where the nude body of her sister, Almeda, was found with a bullet in the chest. She died within a few blocks of the intersection where her sister April stumbled drunk into the street to be struck down by a drunken driver, the son of a white policeman. Such multitudes of tragedies are not uncommon among Indian families and again, alcohol was the ever-present influence.

It is uncommon for health and police authorities to be able to do anything to prevent the damage from alcohol. An exception came last year, when a young Sioux woman who gave birth to four FAS children was jailed by tribal authorities at Pine Ridge, S. D. when she continued to abuse alcohol during the pregnancy of the fifth. The policemen who locked up the pregnant alcoholic are reluctant to speak for the record. One confided, “If the ACLU gets wind of this, we may be in trouble.”

No one wanted to violate the woman’s civil rights, he said. They were only trying to guarantee an unborn Sioux a “safe place.”

Add alcohol related suicides, homicides, highway fatalities, and death from alcohol induced or alcohol aggravated illness and the terror of this plague in Indian country is rivaled only by the genocide of the last century’s Indian wars.

The U.S. Indian Health Service estimates that significant drinking problems are experienced by half the population on some reservations. The federal government declares alcoholism and alcohol abuse the reservations’ number one problem.

Drinking is a factor in 75 percent of Indian deaths and 80 percent of suicides, according to the IHS.

Of the 10 leading causes of death among Indians, alcohol is directly implicated in four: cirrhosis, homicide, suicide and accidents.

In 1986, alcohol abuse was directly related to 52 deaths per 100,000 Indians, compared to 7.8 deaths for non-Indians and 13 deaths for other non-whites.

Alcohol related mortality is consistently higher on reservations than for the total U.S. Indian population. Highly assimilated eastern Indians recently added to the data base have diluted the aggregated figure. In several IHS regions, the death rate is much higher than the national rate; 8 times as high in Tucson, Arizona; 7 times as high in Aberdeen, South Dakota; 6 times as high in Albuquerque, New Mexico; 6 times as high in Portland, Oregon and 11 times as high in Billings, Montana.

IHS measures the severity of the problem in terms of years of productive life lost between birth and age 65. The YPLL (years of productive life lost) scale gives greater weight to the loss of a younger life. A 60-year-old alcoholic who dies of cirrhosis loses 5 years by this gauge. When 16-year-old Stanford Rides Horse died after wandering outside from a drinking party last winter, 49 years of productive life were lost.

A cross section of 100,000 Americans will lose 151 years annually to alcohol related deaths.

The Billings, Montana IHS area, which includes seven reservations in Montana and one in Wyoming, has the highest death rate in the nation. The YPLL rate is an annual 1,725.7 years.

Among Indian women, one in every four deaths is caused by cirrhosis, 37 times the rate in white women. Homicide is three times the national average.

Indian alcoholism and alcohol abuse is not a new problem. In 1786 Bernardo de Galvex, viceroy of Spain, urged that liquor be heavily traded among the Apaches and tribes of the north for profit and to make the hostile Apaches easier to manipulate and more dependent upon the Spanish. Early tragic colonial experience sparked legislation prohibiting sale of alcohol to Indians in Connecticut in 1645.

Other colonies followed Connecticut’s lead. In 1832, Congress passed a law prohibiting sale to all American Indians. This law remained in force until 1953.

One bibliography lists 1,000 references to Indians and alcohol, most from medical and anthropological journals from the past 30 years. A large body of this literature attacks, perpetuates or discredits the “Drunken Indian Myth.” The notion that Indians can’t hold their liquor gained credibility when early researchers demonstrated that Indians were slow to metabolize alcohol.

Convinced of the Indian intolerance for alcohol, medical researchers found “proof” in hospital emergency rooms, as they measured the metabolism of skidrow drunks with liver damage whose tolerance to alcohol had been broken by years of abuse. Other investigators defended Indians against these claims, noting that the drinking style most easily and most often observed among Indians is binge drinking with friends. Since these drinkers do not drink alone, drink daily or exhibit other classic “white” symptoms of alcohol, they must not be addicted to alcohol, defenders reasoned.

Much of the literature quibbles over definitions of alcoholism and alcohol abuse. Some theorists contend that Indians drink like white college students who party excessively on their first escape from parental authority. College students usually moderate their drinking upon graduation to assume responsibility of a job, compete for promotions, marry and raise a family.

Indians start drinking at a younger age and, with no job, promise of promotion and few external cultural controls to cause them to moderate, continue to drink heavily until age 35 to 40 when drinking declines dramatically among this population.

Jill Plumage’s last drunk was a Lysol and perfume binge that ended in delirium tremens. She was banned from her own reservation and had lost her children. She alternated long stays in alcohol treatment units and detoxification centers with binges on skidrow from San Francisco to Wolf Point, Montana.

Today, there are few recovering alcoholics on the reservations of Montana and Wyoming who haven’t heard of this beautiful Gros Ventre-Assiniboine woman. Plumage was one of three founders of the Intertribal Alcoholism Campout, a three-day celebration of sobriety that drew 2,500 recovering Indian alcoholics to Ethete, Wyoming this year.

Recently she celebrated her 11th year of sobriety in a sweat lodge ceremony on a creek beneath the Pryor Mountains. “I’m only one drink away from my old life,” she says. “I am an alcoholic.”

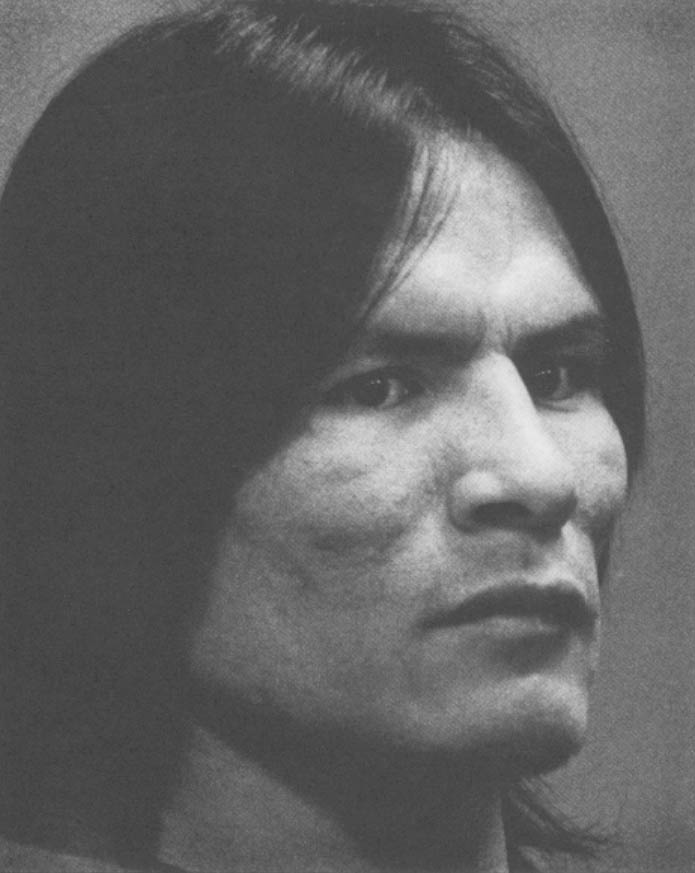

Another now-famous Indian remembers the precise time and place of his last drink.

“It was 3 p.m. on New Year’s Eve in 1969,” said Dennis Banks, founder of the American Indian Movement and a well-known activist in the 1960s. “I was playing the jukebox and shooting pool in Joe’s Bar on East Franklin in Minneapolis. I had heart palpitations and a flash, like you get from a jolt of caffeine. I set my beer on the bar and said, “Percy, give me a 7-Up.”

Banks, who was building a buzz for New Year’s Eve, walked home that night and into the headlines and network news as leader of the militants at the Siege of Wounded Knee. Banks drank heavily for twelve years, the last two on the seamy side of Minneapolis. But while members of Alcoholics Anonymous profess to be “powerless over alcohol” Banks says he is not.

“I quit the first time I tried. I have an inner strength.”

Arguments that Indians have a deficient ability to metabolize or process alcohol were put to rest in the mid 1970s by studies with controls on important variables of body weight and drinking experience. These investigations found no difference. More recent studies may give Indians an edge.

No researcher in this field is more respected nor more quoted than Professor Philip May, Ph.D., of the University of New Mexico. May contends there are many varieties of Indian drinking, but binge drinking is the most visible and discussed.

Indians who are acculturated generally drink like the segment of modern society with which they identify, he says. Indian professionals and bureaucrats generally drink like other professionals and bureaucrats. Indian laborers drink like other laborers.

When all the scholarly dust settles, Indians prove much like other peoples newly introduced to alcohol. But researchers do believe that something can be done to speed acculturation to liquor. May is only one of a number of concerned experts and laymen who note that alcohol laws represent a variable that tribes can manipulate.

In 1953, Congress gave tribes the power to legalize the sale of alcohol on reservations. In the 35 years since, 69 percent of the reservations still forbid the sale of alcohol.

Just as it did among Canadians and white Americans in the 1920s, prohibition on reservations generates heavy drinking among Indians. May and others argue that prohibiting alcohol discourages moderate social drinking and encourages binge drinking. Unable to buy alcohol on the reservation, Indians tend to imbibe heavily when they have the opportunity, drinking until they pass out, run out of money, are hurt in a fight or arrested.

Ozzie Williamson, a Blackfeet who spent time in jails from Seattle to New Orleans before becoming a pioneer in the Indian sobriety movement, remembers: “No one quit drinking while there was still booze or money to buy more.”

Studying reservations in Montana, May found there were long term effects of legalization, namely 18 to 47 percent lower mortality rates from cirrhosis, motor vehicle accidents, suicide and homicide.

The overall alcohol-related death rate is 8.8 percent lower for wet tribes than dry.

In some comparisons of similar reservations, wet tribes had 12 percent fewer alcohol-related deaths and 25 percent fewer alcohol-related fatal auto accidents.

But the benefits aren’t immediate and tribal politicians and their constituents aren’t excited by the prospect of saner alcohol use 15 or 20 years from now. May found that the short term effect of legalization–documented on one reservation–was an immediate doubling of alcohol-related deaths.

Legalization may not be politically practical, but if anything is to be done, there is a strong argument for quick action. More than half of the Indians who drink are in school today. Also, new generation Indian Americans are more acculturated than their parents and more receptive to a message from the dominant culture.

Time may be running out. The second phase of the problem is raging among Indian adolescents. Alcohol use begins early among reservation youth. In one survey, 68 percent said they began by the age of 13.

In a survey of seven reservations, 33 percent of juveniles ages nine to twelve were regular drinkers. The grim statistics continue–use of all drugs is 24 times the national average among Indian adolescents and Indian youths are six times as apt to use marijuana as non-Indian teens.

Drinking is the main reason one of every two Indian students does not finish high school. The suicide rate up to 10 times as high for Indians ages 15 to 19.

The drug and alcohol plague afflicting Indian country may be only a prelude to the epidemic that is coming in the third phase. Currently, one in three alcoholics in the U.S. is female. But the devastation is much, much worse among Indian women. Three of every seven teenage Indian alcohol abusers are female, according to the IHS.

The over-burdened nurses, social workers and foster parents trying to help alcohol-damaged children point to the depressing figures with the horror of knowing how much worse the situation can get. More than 60 percent of the 1 million Indians and Alaskan natives are under 30 and the birth rate is 83 percent higher among this population than the U.S. rate.

It is a medical fact that one of every four drinking mothers will give birth to a FAS baby. An alarming number of Indian children are born with FAS or some FAS effects. These children often are retarded in growth, have abnormal looking faces and are deficient mentally.

Too often, the misery is compounded. Twenty five percent of Indian mothers who have one FAS child have another.

The incarceration of the young Sioux woman came too late. Jeaneen Grey Eagle, director of Project Recovery in Pine Ridge, reports that the woman’s fifth child also was “born FAS.”

FAS children, because they almost always require foster care, extensive medical care and special education, cost the state an annual $30,000 each. With an average IQ of 68, many require institutional care at a cost of more than $60,0000 per year.

Just that one woman’s five children could cost the state $150,000 to $300,000 per year.

The epidemic too many fear is coming will dwarf the $50 to S60 million the IHS spends on alcoholism programs.

In the meantime, there are scattered efforts by tribal councils to cope, control and defeat alcohol’s deadly grip.

The day after Alfredine Old Crane’s murder, Larry Hopkins, president of the Billings American Indian Council, wrote to the Billings Gazette:

“Alfredine Old Crane was the victim of more than a murder. She was brutalized by the system.

“Tuesday evening, Alfredine’s body, stripped of its dignity and most of its clothing was on the 5:30 and 10 p.m. news. Both channels 8 and 2 led their evening newscasts with the story. Wednesday morning, the same view of Alfredine’s brutalized corpse appeared on the front page of the Billings Gazette.”

At a news conference, Hopkins said of Alfredine’s indignity, “it wouldn’t have happened to a white woman.”

A few days later, a social worker in the same city, Grey Eagle, is captive of the telephone in a desperate attempt to find an opening for a young woman seeking drug and alcohol treatment.

“We’re understaffed and underfunded,” she said. “Ask the IHS why it spends less than 2 percent of its budget on what it calls its number one problem.”

Grey Eagle fields a call from a treatment center. Bad news. There were no beds available. “This young woman is ready for help. We could lose her if she doesn’t find it,” she says.

The plague sweeping Indian country angers and frustrates professionals like Grey Eagle. Justified or not, the blame is quick to be placed at the feet of the federal government. “The U.S. wouldn’t let this happen to white people,” she says.

Her attitude is common, as those picking up the broken lives of alcohol’s prey look to those in power to deliver them from their heart-breaking labors.

©1989 Roger Clawson

Roger Clawson, on leave from the Billings (MT.) Gazette, is writing about alcohol abuse by Indians.