Roger Cohn

- 1984

Fellowship Title:

- Public Housing in America

Fellowship Year:

- 1984

The Plight of Public Housing

It was surely intended as a paean to the dreams of public housing. There, on the walls of the community building lobby at Richard Allen Homes in Philadelphia, the artist had depicted what the New Deal planners had hoped life would be like in one of the first of the city’s public housing projects: a smiling mother, her baby in her arms, waving goodbye to her husband as he heads off to work, lunch box in hand; a woman sitting on the front steps reading a book while children play on the lawn with model airplanes and popguns; sleek youths in athletic uniforms, playing hard at baseball, football and basketball. The mural has long ago faded. The paint has peeled off in huge chunks, leaving gaping holes in the human figures. What remains is a sadly ironic reminder of a dream that bears little resemblance to current life at Richard Allen Homes. These days, the only athletic facilities on the project’s grounds are the milk crates the kids have nailed to trees as makeshift hoops

The Kenilworth Estates

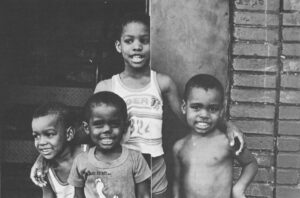

It was, Kimi Gray remembers, simply a matter of recognizing that things could not get any worse. Conditions at the Kenilworth Parkside public housing project in the District of Columbia had become abominable–dozens of apartments had been vacant for so long that desperate junkies just broke in and set up camp, dealing drugs openly on the street and terrorizing residents; overflowing trash dumpsters were emptied so infrequently that they became feeding grounds for rats so huge that mothers were afraid to let their youngsters play outside, and the heating system broke down so routinely that residents planned on spending the coldest winter days huddled around open oven doors. Kimi Gray (in foreground) and two friends at Kenilworth. So in 1979, Gray, an active tenant leader, approached district housing officials with a proposition. She had heard of successful programs in St. Louis and Boston where tenants were managing their own public housing developments. Why not give the residents of Kenilworth a chance to take control of their project? “I told them, ‘Let’s face it, Things have

High-Rise Hell

Take a drive up State Street on Chicago’s South Side and you will begin to get an idea of what went wrong with high-rise public housing in urban America. Start at 54th Street at Robert Taylor Homes, the largest public housing project in the world–28 consecutive buildings of 16 stories each, all of identical concrete and brick construction, with fenced-in, cage-like walkways along the outside of each floor. Then continue north, and on the west side of the street, virtually the only thing you will see for the next four miles is high-rise public housing–five housing projects, all built between 1950 and 1966, each with its own uniform construction mold stamped from the architects’ cookie cutter. By the time you approach the glittering skyscrapers of downtown Chicago, you will have passed 65 buildings containing 8,162 units which house more than 35,000 people, roughly a quarter of the city’s public housing population. If you venture into one of those buildings, you are likely to find conditions that defy the worst stereotypes of public housing. The elevators

The Art of Survival in the Richard Allen Homes

It was a homecoming, of sorts, for Mabel Searles. As a teenager in the 1940s, she had lived for several years in Richard Allen Homes, the sprawling public housing project in North Philadelphia. The new garden-apartment development was considered a showplace in those days, a shining example of what government could do with an urban slum, and Searles’ memories of Richard Alluit WCIC Uf nuatly-Uhnniud lawin and blooming flower gardens and residents who gathered regularly in the auditorium for plays by the Allen drama club or talent shows starring the tenants. Still, when the Philadelphia Housing Authority reassigned her to Allen Homes as the project’s manager two years ago, Searles had no illusions. She recognized that much had changed at Allen over the past four decades, just as it had in many other inner-city neighborhoods and housing projects. In fact, Allen had become known as one of the toughest of Philadelphia’s projects, a place where drug dealing and its related violence were everyday happenings. Searles knew all about that reputation. But she also knew that