It was a homecoming, of sorts, for Mabel Searles.

As a teenager in the 1940s, she had lived for several years in Richard Allen Homes, the sprawling public housing project in North Philadelphia. The new garden-apartment development was considered a showplace in those days, a shining example of what government could do with an urban slum, and Searles’ memories of Richard Alluit WCIC Uf nuatly-Uhnniud lawin and blooming flower gardens and residents who gathered regularly in the auditorium for plays by the Allen drama club or talent shows starring the tenants.

Still, when the Philadelphia Housing Authority reassigned her to Allen Homes as the project’s manager two years ago, Searles had no illusions. She recognized that much had changed at Allen over the past four decades, just as it had in many other inner-city neighborhoods and housing projects. In fact, Allen had become known as one of the toughest of Philadelphia’s projects, a place where drug dealing and its related violence were everyday happenings. Searles knew all about that reputation. But she also knew that most of Allen’s tenants were dedicated to improving their community, and she wanted to show her willingness to work with them. So her first week on the job, she came to Allen on a Saturday, her day off, to join in a block cleanup and barbeque.

The cleanup had ended, and Searles was relaxing in a lawn chair and chatting with the tenants, when suddenly she heard loud popping noises from the next courtyard. She turned and saw two young men, pistols in their hands, facing each other as they circled the pavement and exchanged gunfire. She sat frozen with fear for a moment, before she realized that the chairs around her were empty and the courtyard deserted. At the first sound of gunshots, the tenants had instinctively grabbed the children and run for cover.

“They’d been through this so many times before that they knew not to wait around to see what was happening,” Searles said. “It’s another world down here, and the people who live here know what they have to do in order to survive.”

Surviving. It is a description of life in Richard Allen Homes that is used with frightening frequency by the people who live there. Indeed, living in Allen is a struggle for survival. To survive, one must learn to avoid the violence that is routinely perpetrated by drug pushers who flock to the project because they know its maze of courtyards and hallways make for an easy getaway. To survive, one must learn to cope with an overloaded, antiquated plumbing system that at times causes raw sewage to back up through sinks and bathtubs and pour onto the floor. To survive, one must learn to live with an outmoded electrical system that fails to meet minimal safety standards and frequently causes blackouts that can last for days.

And perhaps most of all, to survive in Allen Homes, one must deal with a sense of living apart, separated from the rest of the city not by bars or fences but by something far more insidious-a frame of mind. For what emerges after more than two months of extensive interviews and conservations with Allen residents are portraits of people who feel cut off from the surrounding community and have little hope of ever leaving a decaying housing project that they fear has been abandoned by the federal and city governments.

It is a frame of mind that is all too common among residents of the nation’s federally-subsidized, lowincome housing system. Not that Richard Allen can be called typical; even for a big-city housing project, it problems are more severe than most. But it is hardly unique. Among the 43 public housing projects operated by the Philadelphia Housing Authority, of which Allen Homes is the largest, at least a dozen have problems comparable to Allen’s. And those problems are not very different from those found in public housing in cities from Detroit to Dallas, from Newark to New Orleans.

In the case of Allen Homes, named for the former slave who founded the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the residents’ sense of separateness is reinforced by a physical isolation. The 1,324-unit development consists of a patchwork of asphalt courtyards and redand-tan brick buildings of three and four stories, all concentrated in an area of eight square blocks. When it was built in 1942, Allen Homes was planned as part of a slum rehabilitation project that was never completed. Today, a hodgepodge of vacant lots and abandoned houses dominate the North Philadelphia neighborhood surrounding Allen. The only remaining stores in the immediate area are a couple of mom-and-pop groceries-their windows boarded up, their doors covered with bars. For many tenants, the weekly ten-block trek to the supermarket uptown is one of the few times they go beyond the project’s boundaries.

It is not uncommon to find three-and sometimes even four-generations of the same family living in Allen, with the last two generations never having lived anywhere else. And in part because of the isolated nature of the project, a host of cottage industries have flourished, with apartments being used as speakeasies that sell liquor and beer or as snack shops that offer ice cream and potato chips. The minimal income generated by such enterprises is sorely needed in a place like Allen where, according to housing authority statistics, more than two-thirds of the families are dependent on welfare and only one in every 14 households has even one family member employed. Of the estimated 5,500 people who live in Allen, nearly all are black.

Certainly, problems such as chronic unemployment, welfare dependency and violent crime exist not only in public housing projects like Allen Homes, but in many poor, inner-city neighborhoods. Yet there is an intensity to these problems in Allen, heightened by the isolated, institutional quality of project life, that fosters a sense of despair that can be seen even among those residents struggling to make Richard Allen a better place to live.

“Richard Allen is really the deepest part of the ghetto,” said Shirley Hill, 37, an active tenant leader. “It’s not that the things that go on here don’t happen on the outside. It’s just that everything is so much more concentrated here.”

“This is a city within a city,” Larry Wyatt, 30, remarked as he sat on the steps outside his Allen apartment. “They shouldn’t call it Richard Allen Homes or Richard Allen project. They should call it Richard Allen province, because this is a separate province of North Philadelphia . . . This really is another world down here, man, a whole other world.”

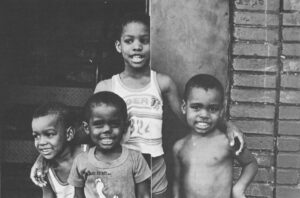

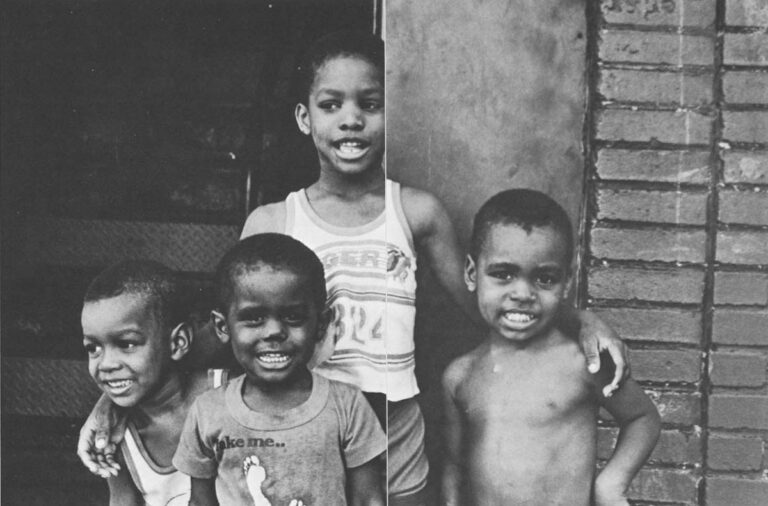

It was the kind of hot, sticky summer afternoon when the courtyards of Richard Allen Homes teem with life. On the crumbling asphalt, girls played jump rope using a strip of torn clothesline, while boys shot baskets against a backboard fashioned from wood they had torn from the window of a vacant apartment and then nailed to tree. Through the maze of children, a man in a white T-shirt and khaki shorts pushed a shopping cart filled with cooked crabs he was hawking as he called out in a deep baritone, “Crab man, crab man.” Out of one doorway came a young man clutching a quart of beer he had just purchased at a speakeasy upstairs. A few doors down, teenage boys whose faces could not yet sprout whiskers were huddled over the steps in the heat of a craps game, waiting for the next roll of the dice.

In a corner of the courtyard, in the shade of a towering beech tree, Bob Wells and Dave Taylor had gathered with a half-dozen friends who were seeking some relief from the heat. It already had been a tough day for Wells and Taylor, both of whom are 41 years old and have lived in Allen Homes nearly half their lives. Wells has not had a steady job in more than seven years; Taylor has been without work for almost two years. This morning, Wells had arisen at 5 a.m. and taken the trolley to a construction site where he had heard that laborers were being hired for the day. After waiting in line more than an hour, Wells was told he did not have the necessary union card and so could not work. Taylor, meanwhile, had made yet another fruitless trip to the state unemployment office, only to learn again that he lacked the skills for any available jobs.

“I can see them saying if you’re able-bodied, you shouldn’t get welfare,” said Taylor, a soft-spoken man whose daughter and granddaughter also live in Allen. “But they tell you this and then they never tell you about any jobs. I’m able-bodied, but I can’t be too able if I can’t get work.”

The mood grew even more sour as the talk turned to life in Allen Homes. Ben Clark shifted in his folding chair and scowled. “This place reminds me of a prison,” he said. Everywhere you look there’s nothing but brick walls and pavement, just walls and pavement. It’s all so closed in, like there’s no way out of here.”

Bob Wells, who was sitting on a fence railing a few feet away, shook his head in disgust. It was not the first time he had heard Allen Homes likened to a jail; in fact, that image is used with disturbing regularity by the people who live there. Such talk bothers Wells, who had been president of the tenant organization a few years ago and had found it to be an extremely frustrating experience.

“The disrepair the housing authority keeps this community in, I think it begins to psychologically affect the tenants,” said Wells, a stocky man with dark-rimmed glasses and a goatee. “If you see the city letting narcotics flourish in your community, if your toilet doesn’t flush because they won’t come fix it, if your lights don’t work, if your trash isn’t collected-all that starts to make people unconsciously believe that they don’t deserve any better.

“It’s what I call the project mentality. Mentally, it’s not really home, it’s not really a community. It’s just a place for me to live until I can get someplace else.” Wells paused, then added, “Of course, most of the people here never get any place else.”

Wells has lived in Allen Homes since 1968, when he moved into a three-bedroom apartment there with his wife and five children. For the Wells family, as for many longtime residents of the project, coming to Allen Homes had been a step up. The Wells’ had been living in ramshackle buildings in South Philadelphia-first in a dilapidated house that had a gaping hole in the living room floor and that was finally condemned; and later in a cramped, three-room apartment with the bathroom down the hall and rats so big that Bob Wells used to shoot them with a pistol. Indeed, with Wells unable to find work, the apartment that the family obtained at Allen Homes for a rent of $59 a month was a godsend. Though the rent has since risen to $106 a month, it is still far less than they would have to pay even for slum housing on the private market.

The Allen Homes that the Wells family first encountered 16 years ago was vastly different from the project that exists today. Like other prospective tenants, the Wells’ were screened and their previous residence was inspected to make sure they would maintain a decent home. Such screenings and inspections have since been discontinued, following the court decisions ruling that these practices violated an individual’s civil rights. For more than two decades, Allen Homes, like other inner-city housing projects, has been steadily losing the working-class families that once helped provide stability and a dependable rental revenue. That process was accelerated during the 1970s, as cutbacks in federal funding and city services led to a drastic reduction in the project’s maintenance staff and security force. As a result, Allen Homes, which once provided decent housing for low-income families, has now become the housing of last resort for the dire poor.

“What’s missing in Richard Allen is the sense of community that was still here when I first got here,” Wells observed. “Somewhere between the 1940s and today, that project mentality started seeping into the people who live here, so they stopped seeing Richard Allen as Richard Allen Homes and started seeing it as Richard Allen projects.”

While the others were talking, Taylor had gone to fetch a set of metal horseshoes and posts. Now, he rounded up Wells and a couple of other fellows, and they all headed for a game of horseshoes at the city playground that borders the project on Poplar Street. Once, this playground had boasted well-kept baseball and football fields where teams from Allen Homes competed with those from other housing projects. But seven years ago, the city gave up a large chunk of the playground because it lay in the path of a proposed commuter railroad overpass. Without that land, the playground could no longer sustain ball fields, and today, all that remains is a basketball court, a toddlers’ play area and a small clearing covered with knee-high grass. It was on the edge of that clearing in the shadow of the overpass, that the men set up their horseshoes game. They played until dusk, with the occasional rumble overhead of the trains that carried the commuters home to the suburbs.

“They took away our ball field, a place for our kids to play, just to build this,” Wells said, pointing up at the overpass “It’s another example of the city telling the people of Richard Allen that your community’s not worth a damned thing.”

They call her Miss Pearl. It is a title she earned not only by virture of her age, for Pearl Holland is 73, but also because of the deep respect her neighbors feel for her. She has been the community leader in her coutryard at Allen Homes since moving there more than 20 years aloo-organizing Saturday cleanups and group barbeques, volunteering as a cook for youth programs and helping troubled neighbors who need someone to watch the kids or go to the store.

On this particular morning, Miss Pearl was out in the courtyard, with broom in hand, sweeping up bits of broken glass and paper that had accumulated in recent days. She had been outside, anyway, Miss Pearl explained, because her husband John had set off a can of poisonous vapor in their apartment to rid the place of roaches. The bugs had been infesting their tidy, three-bedroom unit for months, she said, ever since the woman upstairs started leaving trash in the hall. When it came to pest extermination, the housing authority was considered extremely unreliable, and so John Holland, who had become something of an expert in killing roaches over the years, had taken matters into his own hands. Miss Pearl said she was enjoying sweeping the courtyard far more than she would enjoy sweeping up the hundreds of dead roaches she would find on the floor when she went back inside.

The bugs were not the only problem bothering Miss Pearl. She told of how the housing authority had repeatedly failed to deal with two hazardous situations plaguing her courtyard. In one entryway, four of the six apartments had been vacant and had fallen prey to vagrants and junkies who hung out in the hall and slept in the abandoned units. The stench of urine permeated the hall, and in one of the empty apartments, two broken syringes were plainly visible amid the trash scattered on the floor. The neighbors had been asking for weeks to have the vacant units sealed and the hallway locked, she said, but so far, the housing authority had done nothing. The authority also had not taken steps to repair a busted sewage pipe in a nearby basement, even though the problem had been reported months ago and the cellar had been routinely flooded with raw sewage ever since.

“It’s not that the people who live here don’t care about Richard Allen,” Miss Pearl said. “It’s just when people have to live with things like this, it makes them discouraged-mighty discouraged. And a lot of them just give up.”

Not Pearl Holland. In the small plot of dirt outside her apartment she had planted grass and an immaculate flower garden of sparkling marigolds and stately lillies of the valley. This afternoon, after she had finished sweeping the courtyard and the dead roaches inside, she planned to turn over some fresh dirt to make way for a patch of cabbage and collard greens.

“People say to me, ‘Miss Pearl, why you fixing up so nice? This is just a project, it’s not your home.’ ” She bent down to pick up some litter that had blown into her garden, then looked up. “Well, this may be just a project, but as long as I’m living here, it is my home.”

Eloise Johnson had also made a home for herself and her three children at Richard Allen. She had moved there five years ago, afer she had separated from her husband and had found herself with no income but welfare and with no place to live. With painstaking care and great pride, Johnson, 40, had set about changing her dingy, two-bedroom apartment into a lovely home. At her own expense, she had painted the entire apartment, installed carpeting, hung flowery wallpaper and sleek wood paneling and decorated one living room wall with mirrored tile. Using the $45 she earned each week from a part-time job as a health-care aide, she had been able to purchase a red velveteen couch on credit from the furniture store uptown. Even housing authority officials said the Johnson place was among the finest in all of Richard Allen. But that was before the flooding began last year.

The first incident occurred last September when a pipe under the kitchen sink burst and hot water began pouring onto the floor. By the time the gushing had stopped, the apartment was flooded with more than a foot of scalding water, and the Johnsons had to wait until the next morning to return and try to salvage their belongings. When the next flood occurred three months later, however, there was far less left to salvage. This time, the sewer main became clogged, causing raw sewage to back up and overflow from the toilet, the bathtub and the sinks. It kept overflowing until the place was filled with nearly two feet of brackish water and filth, creating a sight so disgusting that Eloise Johnson is still embarrassed to describe it.

“Each time the people in this row used their bathrooms, I had it in here,” recalled Johnson, a frail woman with tired eyes. “One minute we’d have urine coming out here, the next minute we’d have human waste and the next minute we’d have bubbles and some kind of perfume smell from somebody taking a shower.”

Housing authority officials are well aware of the severe maintenance problems that exist at Allen Homes. But they point to the project’s aging, decaying plumbing and electrical systems and to two major realities they must face-lack of funds and shortage of manpower. Because of budget cuts, Allen’s maintenance crew, which totaled more than 50 people only 12 years ago, has now been reduced to 17. And the authority has little hope of obtaining the millions of dollars that would be required for a badly-needed reconstruction of Allen’s major utility systems, which have not received an overhaul since the project was built 42 years ago.

As for Eloise Johnson, she now desperately wants out of Allen Homes. The flooding sewage ruined her carpeting, her wallpaper and most of her furniture, and she has no money left to replace any of it. “I had one of the nicest places in here until this happened,” she said, her voice choked wtih emotion. “Now, I want to be any place but Richard Allen. Just let me have a decent place for me and my children, that’s all I’m asking.”

Across from the Johnson place, Jennette Walker operates a candy store from the window of her firstfloor apartment. What began last year as a way to earn some cash has blossomed into a full-scale enterprise, complete with a freezer chest for ice cream and ices and a display rack for chips and snack food. On summer nights, the Walkers’ store is a regular stop for the children of Allen Homes.

One recent evening, Valencia Williams, an eight-yearold girl with braided hair and a fetching smile, came to the Walkers’ window, quarter in hand, to buy a cup of grape ice. Valencia had earned quite a reputation in Allen Homes for her wonderful singing voice, which had been displayed at the project’s talent show and at the neighborhood Baptist church. A few adults who had been chatting nearby paused to tell Valencia how beautifully she sang. The girl simply smiled shyly and looked down at the pavement.

Suddenly, yelling was heard from outside the next entryway. A teenage brother and sister were arguing, apparently because the brother had stained her shoes when he sprayed their apartment with roach poison. The girl hurled vicious insults at her brother, who finally responded by smacking her in the side of the head. When she persisted, he kept swinging at her and chased her until he wrestled her to the ground and began to pummel her with his fists. At this point, the teenagers’ mother, a haggard-looking woman who had obviously been drinking, came charging across the courtyard and tried to break up the fight. Her son kept pushing her away, and the mother reached into her pants pocket and pulled out a folding knife. She opened the long blade and loudly warned her son to stop hitting the girl. When he refused, the mother lunged forward and stabbed her son in the arm.

Valencia’s face had shown no expression as she had watched the fight unfold. A visitor, disturbed by what the child had witnessed, tried to distract the girl from the grim scene across the courtyard. Does she ever get a chance to practice her singing at home, the child was asked?

Valencia looked up, and her eyes were clouded with tears. “No,” she said softly. “There’s no real place to sing around here. But in my mind, I sing. In my mind, I sing to myself all the time.”

©1984 Roger Cohn

Roger Cohn, reporter on leave from the Philadelphia Inquirer, is investigating public housing in America.