Russell Clemings

- 1989

Fellowship Title:

- Salt, Selenium and the Future of Irrigated Agriculture in the West

Fellowship Year:

- 1989

“The Gift of the Indus”

If any one place deserves to be called the birthplace of modern irrigation, that place is the Punjab, a sandy triangle of pancake-flat alluvium where India’s British rulers built the first of their 46 “canal colonies” in 1849. The first colony consisted of only a few thousand Sikh soldiers dispossessed by the British invaders. But today, half a century after India’s four western provinces–including most of the Punjab–were torn off by fleeing colonialists and transformed into what is now Pakistan, 100 million people are coaxing sustenance out of the man-watered soils of the Indus River basin. No other nation has so many people who are so utterly dependent on artificial rain; four-fifths of Pakistan’s food comes from the irrigated Indus plains. No other nation has more to lose if its farms are poisoned by the inevitable build up of natural salts from irrigation, and no other nation is trying harder to avoid that fate. Heroic drainage projects area tradition in Pakistan, and since the early 1950s, a dozen developed nations have sent plane loads of

“A Flood From Below”: The Downfall of Irrigation

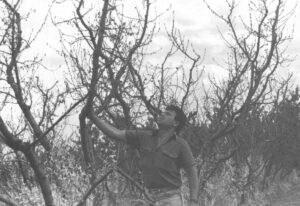

SHEPPARTON, Victoria, Australia–When spring came to the Riverine Plain of northern Victoria in September 1989, Peter Avram’s peach orchard slowly awakened and burst into leaf, just as it always had before. Peter Avram, a peach grower in Victoria, examines trees killed by rising groundwater at his orchard near Shepparton. (Photo by APF Fellow Russell Clemings) Avram expected a good crop, one that might bring $40,000 in sales once the fruit was picked and packed. But two months later he had nothing but a forest of dead wood. More than 2,000 trees, most of them in the prime of their productive lives, got a fatal case of root rot. They were killed by a flood from below, drowned in an unseen tide of rising groundwater caused by 150 years of over-irrigation and deforestation. For a century and a half, Australians like Avram have farmed the low inland plains along the River Murray. They cut down forests of eucalyptus trees to bring in the sun, and laced the countryside with canals to bring in the water. In

Death Traps

Gary Zahm remembers it as just a feeling, a vague impression that something was wrong at the Kesterson National Wildlife Refuge, which he had just been put in charge of. Mostly, it was the smell. “I’ve worked in alkaline marshes all my career,” Zahm said. “And this was an alkaline marsh, but it didn’t smell right. It was like nothing I’d ever smelled before.” There were other signs of trouble: The tips of the cattails were turning brown. Huge mats of algae were floating in the water. And, eeriest of all, the place was utterly quiet. The noises a person would normally expect to hear in a marsh–the croaking of frogs, the splashing of muskrats–were noticeably absent from Kesterson. “It just wasn’t a healthy place,” Zahm said. “There were things missing that should have been there.” That was in October 1980, and as things turned out, it was only the beginning. During the next four summers, prodded by Zahm’s observations and the curiosity of two of its biologists, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service uncovered

Mirage

LOST HILLS, Calif.–On a recent May afternoon when the temperature was toying with triple digits, Dr. Joseph Skorupa, a federal wildlife biologist looking for bird eggs, walked a low earthen levee between two vast pools of shallow water. With light-colored clothing and a broad-brimmed hat, Skorupa was dressed for the desert appropriately, because this place, where the mind-numbing heat can evaporate a year’s worth of rainfall in a couple of weeks, is exactly that, climatologically speaking: A desert. But if this is a desert, then why was Skorupa surrounded by water, more than a solid square mile of water in all? Why, on the plains beyond the pools, were there manicured squares of green and gold crops, instead of the usual desert hues of brown or gray or rust? The answer lies in the one thing that makes the western United States the relative paradise it is today, instead of the moonscape it used to be–its far-flung system of plumbing. Hundreds of reservoirs; thousands of miles of canals and pipelines; countless pumps–all delicately choreographed to