Susan Jacoby

- 1974

Fellowship Title:

- The New Americans: Immigration into the U.S.

Fellowship Year:

- 1974

Immigrants And Schools (Part II)

A Success Story

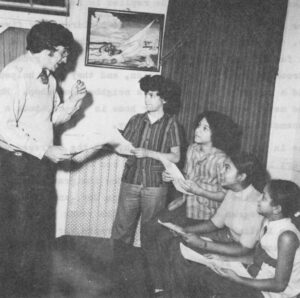

“What do you like to touch?” the teacher asked Meletais Dagres. “I like to touch…money,” he replied in halting English. Dagres left Greece with his wife and children only five months ago. Friends who were already in the United States helped the family find a small apartment above a dry goods store in Brooklyn’s Park Slope section, and they also helped Dagres find a job as a carpenter in a neighborhood shop. Mrs. Dagres, who never worked outside her home in Greece, took a job as a seamstress in a garment factory. No one in the family spoke English, but the Dagreses were able to start learning as soon as their son Costas began attending Brooklyn’s John Jay High School. New immigrants make up more than half of the student body at John Jay, and the school has an unusual program designed to help the young people by teaching them English along with their parents, brothers and sisters, and any other relatives who happen to be living nearby. Teachers visit their students’ homes in the

Immigrants and Schools (Part I)

Old Myths and Modern Realities

Johnny Lo is 16, and he has already been working for three years as a waiter in New York City’s Chinatown. His parents left Hong Kong in 1970 so that their children could receive a free high school education in the United States, but Johnny is not likely to graduate. His restaurant shift begins at two in the afternoon, and he frequently cuts classes in the morning because he is too tired to do his homework when he returns to his apartment after midnight. His English is poor, and he is ashamed because he is two years older than most of his classmates. Lourdes Alfonso was 11 when she left Cuba for Miami with her mother and older brother. After five years in the Miami public schools, she speaks near-perfect English. She wants to go to college and study music after graduating from high school, but she has not made any definite decisions about her future. She is disturbed because a school official has advised her that she would be better off if she looked

The Cubans

MIAMI, Fla. — “The American melting pot is no longer a melting pot,” says Rolando Amador, “but a stew in which you can taste all of the ingredients.” Amador, a Cuban refugee in his mid-forties, runs a neighborhood evening school in the heart of Miami’s Little Havana section. “Little” Havana now sprawls across more than 600 square blocks, and it is only one of the communities dominated by several hundred thousand Cubans who live in Miami and its surrounding suburbs. In many ways, Amador’s school typifies the two-way process of cultural accommodation that has developed in southern Florida during the 15 years of a massive refugee exodus from Fidel Castro’s Cuba. Cubans come to the school to acquire many of the skills they need to survive and prosper in the United States. Women who have put in a full day’s work in garment factories arrive for English lessons after they fix dinner for their husbands and children. Blue-collar workers come for special courses in which they learn how to pass the Dade County licensing examinations

Immigrant Women

The history of American immigration, like most history, has generally been written by and about men. The immigrant woman tends to appear in two guises: the totally ethnocentric mainstay of the family, fighting any outside influences that might weaken her hold on her only domain, and the exploited working girl forced by cruel economic hardship to toil in ways unsuited to “feminine nature.” Popular history and literature provide only sporadic glimpses of the special bravery of women who ventured into a strange land at a time when the vast majority of immigrants were men. They were women who displayed as much courage in dangerous factory jobs as they did in the dangerous childbirth of the poor, and their struggles have not been described adequately. The Italian mill women who carried banners proclaiming “We Want Bread and Roses Too” in the bitter Lawrence (Mass.) textile strike of 1912 have occupied a smaller space in the national consciousness than immigrant girls who were forced into brothels to make a living. In reading the popular press from the