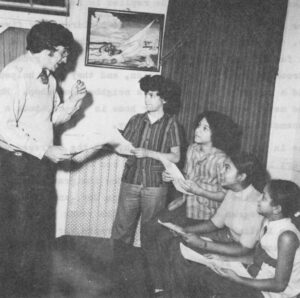

“What do you like to touch?” the teacher asked Meletais Dagres.

“I like to touch…money,” he replied in halting English.

Dagres left Greece with his wife and children only five months ago. Friends who were already in the United States helped the family find a small apartment above a dry goods store in Brooklyn’s Park Slope section, and they also helped Dagres find a job as a carpenter in a neighborhood shop. Mrs. Dagres, who never worked outside her home in Greece, took a job as a seamstress in a garment factory.

No one in the family spoke English, but the Dagreses were able to start learning as soon as their son Costas began attending Brooklyn’s John Jay High School. New immigrants make up more than half of the student body at John Jay, and the school has an unusual program designed to help the young people by teaching them English along with their parents, brothers and sisters, and any other relatives who happen to be living nearby. Teachers visit their students’ homes in the evening for English lessons that are usually conducted around the kitchen table. The Dagreses’ teacher is Rose Schlossberg, who works with Greek and Spanish-speaking families. Mrs. Schlossberg does not speak Greek, but she is teamed with a young interpreter whose family “graduated” from the same program a year ago. The use of former students to work with newer immigrant families is an important part of the project’s effectiveness.

John Jay draws its students from several Brooklyn neighborhoods that have been profoundly affected by the increase in immigration since 1965. It is a multi-racial, multi-ethnic, polyglot school with Italians, Arabs, Haitians, Jamaicans, Dominicans, Greeks and a smattering of Chinese as well as American-born students. Of the 2000 to 2500 pupils who are children of new immigrants, a substantial number have serious difficulties with the English language. Maureen Sloan, director of the John Jay Family Language Program, says there are at least 400 students in the school who do not speak any English. “These are the kids who come to us straight off the plane. Because there are so many of them speaking so many different languages — and with such different backgrounds — you have to develop something of an individual approach. Things would be a lot easier if a big majority of the students spoke one language, the way they do in some Chinese and Puerto Rican neighborhoods.”

The family language program was developed in 1970 partly because John Jay’s principal — whose own parents were immigrants — was unhappy that his mother never learned to speak English well. “We decided the best thing to do was to go to the people instead of trying to get them to come to us,” says Mrs. Sloan. “When I investigated the various English programs for adults around the city, one thing I found was that people tended to drop out after a few weeks. Either they were too tired to take a bus or subway trip to a school at night, or they were afraid of crime if they didn’t know the neighborhood well, or they just felt embarrassed about not knowing English. Having the teachers go into the homes cuts down on all those problems. It’s especially good because so many immigrant parents have exhausting jobs with long hours. When a man and woman have both been working an eight- or ten- or twelve-hour day, neither of them feels like spending an hour commuting to an English class.”

Despite its emphasis on the home, the basic aim of the program is not to teach adults perfect English but to keep the children in school. For parents, the weekly lesson may mean that they learn how to ask for directions on a bus or to buy meat from the neighborhood butcher. For children, the individual attention can provide the extra boost they need to overcome their language handicaps and succeed in school.

And the program makes parents feel the school cares about them and their children — something they frequently doubt because of negative experiences with the educational systems in their native lands. Many immigrant parents of students at John Jay (and at other public schools) say they feel American teachers have more respect for “working people” than teachers did in the countries they left behind. “A teacher will speak to an ordinary person with respect here,” says Mrs. Anna Banca, whose daughter Domenica is an outstanding student at John Jay. “It doesn’t matter that the father isn’t a doctor or a lawyer, only that the child works hard and behaves well in school. A teacher would not come to a working person’s home in Italy. This different attitude is one thing I like about this country.”

The John Jay program is important because it has produced solid evidence of success with students — more success than many highly touted programs billed as “bilingual education” or “English as a second language.” 1 Only 11 per cent of students who enter the school with no knowledge of English make it to graduation. Of students in the family language program — none of whom spoke any English at the start — more than 75 per cent have graduated during the past four years.

Last year, the program reached 350 people in 60 family groups. The total budget for teachers’ and interpreters’ salaries was $62,000 — approximately $1000 per family or $190 per person. Despite the positive results and the relatively modest cost, the John Jay program has been eliminated from the city school budget for next year. The project was financed through the State of New York’s urban education program, but it lost its funding when the state turned over control of the money to the city. The school system’s explanation for the action is that its budgetary procedures do not permit a program that deals with people of different ages at the same time.

For families like the Dagreses, the end of the family language program may mean slower academic progress for the children and no progress at all for the parents. Mr. Dagres has only limited exposure to English because he is usually busy at his workbench. Mrs. Dagres has no opportunity to absorb English in her daily life, because most of the other women in the garment factory where she works are also immigrants who do not know the language. Like all of the families in the program, the Dagreses volunteered when Costas was approached by a teacher and asked if his family would like to learn English at home.

The Dagreses are typical of new immigrant families in one important respect: education was one of the most significant factors in their decision to leave their own country. Speaking through an interpreter — a high school senior who had also been a student in the family language program — Mr. Dagres explained why he left Greece. “I am a carpenter,” he said. “My father was also a carpenter. My wife has no education. I don’t want this life for my children. That tells you everything about why we came to this country (the United States). In Greece, I made it my business to inquire about possibilities for the education of my children. Did you know that last year, 54,000 Greek students passed the examinations to qualify for the university, but there are places for only 10 per cent of them? When you get your high school diploma in Greece, it is written down right on the paper that your father is a carpenter.

“Why should that be? A diploma should tell what kind of a student you are, not what your father does. With places for only 10 per cent of the students, who do you think gets into a university — the son of a government official, a doctor or a carpenter? If a poor student is smarter than a rich one, they will give the place to the rich one anyway. This is why everyone I know left for America. We hoped that our children would have a better possibility to go to school here, and that the lack of education of the parents would not prevent the children from going farther.”

The Dagres family had made considerable progress in English after only three months of visits from a teacher. Both Costas and his younger sister Vicky were able to carry on short conversations in English. Mr. Dagres, who barely knew any words in May, was able to complete short sentences by the end of June; Mrs. Dagres, who has less formal education than anyone in the family, was also able to remember essential household and shopping words. When Rose Schlossberg arrived for the Dagreses’ last lesson in June, they pleaded with her to come back in September. She told them there was no money to pay the teachers and interpreters but promised she would be back if the school could scrape up some new funds. “I don’t do so well,” said Mrs. Dagres sadly, “and this is my only chance to hear English.”

The John Jay program is especially helpful to immigrant the women, because they seldom have the opportunity to learn English in their everyday lives. Many of them work to increase the family income, but they tend to find jobs near their homes in small shops and garment factories staffed by other immigrant women. In their own countries, they generally received less education than their husbands. In the United States, the men are much more likely to find jobs that bring them in contact with Americans (and immigrants from other countries).

Alex Dahab, for instance, works in a bookbinding factory that employs immigrants from half a dozen countries. “We have Greeks, Yugoslavs, Israelis, Arabs — everything. You have to use English sometimes because it’s the only language everyone speaks,” Mr. and Mrs. Dahab and their two sons are among the many success stories of the family language program at John Jay. They are unusual because both parents already knew some English when they arrived in the United States. The Dahabs are Greeks who grew up in Palestine; Mr. Dahab studied in British schools before the 1948 partition establishing the states of Israel and Jordan. He settled in Egypt after partition, but he and his wife decided to leave because they felt there was little economic opportunity for Christians in Cairo. Their two sons, George and Tony, spoke fluent Greek and Arabic but no English when they arrived in New York.

“I don’t know if I would have made it to graduation without the teacher coming once a week,” says 19year-old Tony Dahab. “It was very hard for me at first. I was older than most of the students in the high school, and I didn’t understand any English at all. It was easier for my younger brother. People don’t realize — it’s almost as hard for a teenager to learn a new language as it is for our parents. I already had my education in Egypt. You feel stupid coming into a school and not being able to express yourself about the simplest things. Maybe you were a good student in another language, but it doesn’t matter.” The Dahabs all became so proficient in English that they were “overqualified” for the family language program. Tony, who needed more practice, worked in the program as an interpreter before graduation in June.

The project is frequently as useful to the teachers as it is to the families because it gives them more insight into the cultural background of their students. “We learn things from being in the homes that we could never learn in school,” says Rose Schlossberg, who taught both the Dahab and Dagres families. “And it shows us as human beings to the families. They see that we aren’t monsters from some other planet.” Mrs. Schlossberg established a close personal relationship with the Dahab family; when her husband burned himself in an accident, the Dahabs drove her to the hospital and stayed with her until her own relatives arrived.

The program does not, of course, succeed with every family. In some cases, the parents drop out or listen politely without trying to learn. Herb Teicher, a social studies teacher who volunteered for the program because he is interested in immigrants, described a Dominican family in which the children and mother wanted to learn English but the father did not. “He worked in a restaurant where Spanish was spoken, he watched Spanish TV, he associated only with Dominican people. He was very polite, but he made it clear that he just didn’t care about learning English. On the other hand, I’ve had families in which the people were so interested that they went out and bought extra books and eventually found more advanced classes they could attend. These kind of people will become quite fluent in English in less than a year; they’ll use what they’ve gotten from us as a springboard to a high school equivalency diploma or a better-paying job that requires spoken English. I think the effort of sending teachers into the homes would be worth it even if only half of the people responded — and we get a lot better response than that.”

The elimination of the program from the school budget seems to be rooted in a general apathy and ignorance about the educational problems of new immigrants. Even though some school officials believe immigrants may account for one-fifth of New York’s 1.1 million pupils, the basic attitude seems to be that the new arrivals can take care of themselves. “The immigrants come from all over so they can’t exert any concentrated pressure,” says Maureen Sloan. “No one knows how many of them there are or what they need. Some day we’re going to look back on the 1970’s as a smaller version of what happened with immigrants 100 years ago. But no one seems to know it right now, except the teacher who steps into a classroom in September and hears the kids speaking ten different languages.”

Endnotes

1. “Bilingual education” and “English as a second language (ESL)” both fall under the heading of educational jargon and frequently confuse the educators themselves. ESL classes are available in many urban school systems for blacks, Puerto Ricans, Chicanos and other native Americans with language difficulties, as well as for foreign-born students. They are supposed to use a specific method of teaching English as a foreign language and there has been considerable controversy over the value of such classes for native English-speakers whose speech patterns deviate from standard English. Bilingual education is a more ambitious concept under which students are supposed to be taught all subjects in their native languages until they are able to handle themselves easily in English. Only a handful of American schools have a comprehensive bilingual education program; come school officials refer to any English class for foreign-born students as “bilingual education.”

Received in N.Y. on July 10, 1974.

©1974 Susan Jacoby

Susan Jacoby, a freelance writer, is an Alicia Patterson fellow supported by the Rockefeller Foundation. This article may be published with credit to Ms. Jacoby, the Alicia Patterson Foundation and the Rockefeller Foundation.