BROOKLYN, N.Y. — Natale and Rosa Maria DeCarolis, both in their mid-forties, uprooted their family two years ago to immigrate to the United States. Ton years before, they had left their native Mola di Bari for an industrial town north of Genoa. They finally decided to emigrate from Italy in hopes of obtaining a higher education for their three children — nineteen-year-old Mario, eighteen-year-old Caterina and ten-year-old Franco. Mario and Caterina, who spoke no English when they arrived in 1972, are already fulfilling the family dream at the City University of New York. The DeCarolises are new immigrants, but they are the products of a long immigrant tradition.

MOLA DI BARI, Italy — Signora Columba DeLiso has a house and a lifetime of memories in Mola, but her three children live in Brooklyn. Rosa Maria DeCarolis in her only daughter. “I grew up in an age when mothers kept the children — especially the daughters — very close to home,” says Signora DeLiso. “But I am not surprised that my children have ended up in the United States. There is a better life for them there. But, even though I have visited my sons and daughter in America, I cannot bring myself to leave the town where I have spent my whole life.”

| Signora Columba DeLiso of Mola |

More than forty years ago, Columba DeLiso rejected her husband’s repeated appeals to join him in the United States. The money he made as a fisherman off the Alaska coast was fabulous by Mola standards, but he did not want to be alone and Signora DeLiso did not want to leave her home. In 1932, he returned to Mola to be with his wife. “I suppose I was afraid of the unknown,” she says. “It is strange, especially because I have always felt our family was bound to America by the years my husband spent there. That’s why it doesn’t seem strange to me, that my children should have ended up as Americans.”

At 78, Signora DeLiso still possesses a worn beauty that cannot be captured in ordinary photographs. Her graceful, erect carriage, lively smile and snapping brown eyes have survived hardships that her children and grandchildren have never known. When she talks about subjects that are important to her, her face takes on a determined expression resembling that of her granddaughter Caterina, “I think I would be just the same as my grandchildren in America if I had gone to school when I was a girl,” she says. If I had been born today, instead of almost eighty years ago, I would go off to college too.”

Columba was the oldest of three children, and her mother died when she was nine years old. Her father was disabled, and she assumed the responsibility of running the household. “It was expected, at that time, that the oldest daughter would take over if anything happened to the mother.” When Columba became a teenager — a young woman of marriageable age by the standards of the day — she moved in with an aunt. She looks back on the way her marriage was arranged without bitterness or sentimentality.

“Marriages were arranged by the family — that was accepted. A member of the boy’s family, an older woman, would come to your family and say that the boy was looking for a wife. Often you didn’t know the boy until you became engaged. I did not know my husband, because he had already been a fisherman in America for many years when he returned to Mola to look for a wife. I used to do some sewing in a house near the house of his sisters. One day, his sister came and asked if any of the sewing girls would make a good wife for her brother. My name was mentioned. That was how it happened.

“I was only seventeen, and you can imagine that I was very frightened. He was thirteen years older than I, and he had no education. I had a little schooling, and I wanted a man with more education — I always thought of school as being very valuable. If my mother had been alive, I would have gone to her and told her I preferred to wait for another man. But I couldn’t say that to my relatives. They were feeding me, and they told me it was necessary for me to get married soon. So I really had no choice.”

Francesco DeLiso returned to America to make money after he married Columba. Like many Mola men, he migrated back and forth across the ocean between his family in the old world and his job in the new, Columba was alone most of the time: an experience shared by many Mola women of her generation, “It was very hard to be alone, to bring up children alone,” she remembers. “Women couldn’t go out of the house alone if their husbands were gone, or people would think they were bad. Wives wouldn’t see their husbands in America for years at a time. But that was the only way of keeping the family together when you couldn’t make any money here. And keeping the family was the most important thing to all of us, men and women.

The entire time my husband was in America, it didn’t seem real to me that I was married. We were almost stranger — she was someone who returned from time to time. It wasn’t until after the war, when young people started getting more education, that they started demanding the right to choose their own husbands and wives.”

Francesco DeLiso asked his wife to join him in the United States many times, but she always refused. “My husband wrote me over and over again to come, but I always said no. We argued constantly, in our letters. It’s hard to explain today why I didn’t come. We had a different view of marriage here. With so many men off at sea, it didn’t seen so strange for a husband and wife to be separated. Most of the women my age were at home, and none of them went alone to join their husbands. Finally, though, I wrote my husband that I would come home to America if he would come home and get me. He never got the letter, because he was on his way home with his savings. So we stayed here. I may have been wrong not to go. Our children would have had a much easier life in America. For one thing, we wouldn’t have lived through the war here. But everyone has his own destiny.” The DeLisos were better off than many Mola families because of the money Francesco saved in America, but their economic Position was destroyed by the war. “After the war,” Columba remembers, “everyone talked of immigration again. But my husband felt he was too old to start over, and, besides, it was almost impossible to get a visa.”

In 1958, Columba DeLiso’s oldest son jumped ship and entered the United States illegally. Under the old quota system, he had no chance of enter legally because the family had no immediate relatives in the United States. “My son wanted to make more money,” says Signora DeLiso, “but he was always worried about his illegal status. So he wrote me that he was coming home, he couldn’t stand the worry anymore. I was very happy because I had been worried about him. I painted the house. Then — eight days before I expected him — I received a letter saying he had married an American girl. I was astonished. I threw the letter across the floor. I wondered whether she was a good girl or not. Of course, since then I have been to America and seen that she is a good wife and mother and that she loves my son. But it was so sudden, I could hardly adjust to it.” (Marrying an American citizen is one sure way for an illegal immigrant to legalize his status. Wives and husbands of American citizens have an automatic right to remain in the United States, regardless of how they entered the country.)

Senora DeLiso’s younger son followed his brother to the United States. Rosa DeCarolis was the only one of her children who left for northern Italy before she immigrated to the United States.

“I am not sorry my children went to America,” says Signora DeLiso. “My sons weren’t poor, but if they made one dollar here, they made two in America. The house I live in was built with American money. And the education my grandchildren are getting — well, that just isn’t possible here, even today. My grandchildren would have gone to high school here, but not to college the way they will in New York. And, you know, I believe a woman should have an education as well as a man. When I was a girl, even the priests would say a girl shouldn’t go to school, because it will make her a bad girl. But I am happy my granddaughters will go to school. And when I think that both Mario and Catya are in college — well, that is a great happiness to me. My husband died in 1971, and it would have been a happiness to him too.

“Somehow, I think I always expected the children would leave. My husband liked the United States very much, and he was always telling them stories about America. Immigration was not a strange idea in this family. But my children will not come back the way people of my husband’s generation did. My second son married a Mola girl, and he took his wife with him. My grandchildren all speak English, and their future is certainly in America. I love my own town very much, but I think for the young people there is a better life in America. When my husband asked me to come to him in America, I would have gone if I had known what I know now. For my children and grandchildren, I am content.”

Natale DeCarolis comes from a poorer Mola family than his wife. The men in his family have been fishermen for many generations; they never emigrated and made the large American salaries that have contributed to the support of so many families in Mola. The DeCarolises are the kind of proud, poor people whom the wealthier citizens of Mola describe as “povera, ma una buona famiglia (poor, but a good family).” The accent in on “good,” meaning that the family members took care of each other in spite of poverty and never violated the social codes of the Mezzogiorno by accepting charity from outsiders. The southern Italian attitude toward poverty bears little resemblance to American attitudes. In the Mezzogiorno — even in a relatively well-off town like Mola — poverty has long been the rule rather than the exception. It is regarded more as a somewhat inevitable natural catastrophe than as the result of shiftlessness or laziness. “The DeCarolis children were very, very poor when we were growing up,” recalls one matriarch who can recite nearly everyone’s family history. “I can remember that they didn’t have shoes, and that wasn’t in the bad time after the war* It doesn’t surprise me that they’ve worked very hard in America — I’m sure they wanted to give their children all the things they never had themselves.”

Natale DeCarolis’s parents are dead. His sister, Nicola Lacerignola, is the oldest member of the family living in Mola. He has one brother in the United States and a sister who in about to emigrate with her husband. Natale’s nieces and nephews are all considering emigration in order to make a better living.

Nicola Lacerignola is in her fifties; her husband, a bricklayer, was disabled in an accident. She says she frequently thinks about leaving for America in spite of her age. “Natale didn’t know if he would like the United States,” she remembers, “because he and Rona were very happy in the north of Italy. He wasn’t happy here though. He was always too…ambitious for his family to be satisfied in Mola. When he talked about leaving, he always talked about the education of his children. When he and Rosa write about their children being in college, it’s like a dream for us. None of us could even think of finishing high school when we were growing ups” Signora Lacerignola has two daughters and three sons, and she says she would not be surprised if all of her sons left Mola. One is already working in the Fiat factory in Turin and is engaged to an Italian-American girl in the United States.

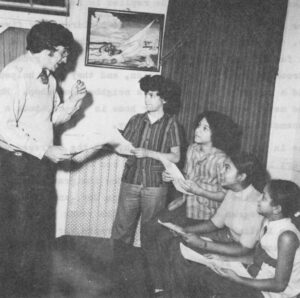

| Another Mola family (Nicola Lacerignola, center) |

While I was in Mola, Signora Lacerignola’s son wrote his mother that he planned to leave for the United States within the next few months. “I’m trying to hold him back because he’s only 22,” she said with a sigh. “But I doubt that I can, especially since he’s seen how well his uncles have done. And, of course, immigration is best for the young. If Natale is happy in America at his age, it will be even easier for a young man starting out.”

Nicola Lacerignola’s youngest song Giuseppe, is about to begin his service in the Italian army. I asked if he ever thought of emigrating. “Emigration?” he asked with a laugh, “Of course. No one with any ambition talks of anything else.”

Author’s note: Part III will examine the life of the DeCarolis family in Brooklyn.

Received in New York on October 16, 1974.

©1974 Susan Jacoby

Susan Jacoby, a freelance writer, is an Alicia Patterson follow supported by the Rockefeller Foundation. This article may be published with credit to Ms. Jacoby, the Alicia Patterson Foundation and the Rockefeller Foundation.