Theo Emery

- 2015

Fellowship Title:

- The Birth of the U.S. Chemical Warfare Service

Fellowship Year:

- 2015

The House Over Hades

In June of 1996, Kathi Loughlin’s phone rang at work. It was her child’s nanny, and she was frantic. “Something is going on here, you need to come home,” the nanny said, a note of panic in her voice. Loughlin had trouble understanding what exactly was happening on their quiet street in Washington’s Spring Valley neighborhood. “Men in space suits,” the nanny said. “I’m just going to get out of here, I’m going to take the baby out of here.” “Just stay home,” Loughlin told her. “I’ll come home right now.” She sped to the house in her car. When she turned onto Glenbrook Road and drove up to her family’s brick colonial home, she was stunned at the sight that greeted her. Trucks clogged the street, and about a half-dozen figures in white suits, gloves and boots teemed around her driveway. Breathing through masks, they were unloading equipment and putting up street barriers to prepare for some kind of work at their neighbor’s house, the residence for the president of nearby American University. Loughlin

The Scientists Who Created America’s War Gases

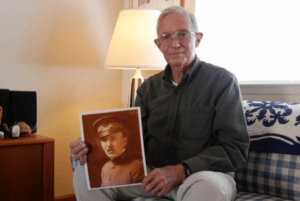

SONORA, Calif. — In a back room of L. Philip Reiss’ condominium, the retired chemical engineer has covered the walls and filled his drawers with mementos of a long life in science. In one corner, he’s hung keepsakes from years volunteering with a Boy Scout troop. In a small wooden cabinet, he keeps his grandfather’s collection of semi-precious stones. And in a drawer under his computer desk, he keeps baggies filled with vials of chemicals. Crystals and powders filled the carefully marked samples. One vial contains a single, fat crystal labeled “Pydrin,” a keepsake from his years of developing pesticides at Shell Chemical Company. Another contains yellow sulfur crystals, resembling lemon-colored sugar. Not every batch of chemicals from his laboratory is among the jumble of vials in his office. About 30 years ago, one of Reiss’ colleagues cooked up a small sample of an arsenic-based compound called lewisite, a combination of arsenic trichloride and acetylene. This wasn’t just any compound — it was an extremely toxic chemical weapon agent dating from World War I. Nicknamed

“History is Repeating Itself:” A Century of Chemical Warfare

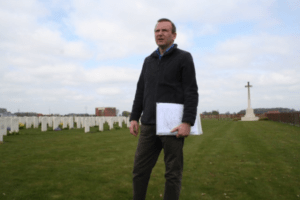

IEPER, Belgium — The breeze blew in from the east as Simon Jones crossed a newly mowed field in Flanders. It was a brisk April morning. He followed a green ribbon of grass that stretched across the pasture and ended at a marble archway. On the other side of a hedge lay rows of marble headstones. At Jones’ back, the long blades of wind turbines turned slowly in the distance, the towers rising beside a canal not far from where the German lines lay in December of 1915, when clouds of phosgene, an industrial chemical, blew downwind into the British trenches and bunkers where soldiers lay sleeping. Jones stopped short of the cemetery, one of almost 200 British graveyards from World War I near Ieper, where the Germans battled the allied armies back and forth for four years. Turning to face into the wind, Jones told me that some of the first soldiers ever killed by phosgene were buried here. Military Historian Simon Jones in Dozinghem Cemetery outside Ieper, Belgium. Some of the first mustard

Downrange in D.C.: What Happens When a Neighborhood is Sitting on Old Chemical Weapons?

The ordnance team had been downrange about 20 minutes when the artillery round surfaced. Inside a hanger-sized tent in the Washington, D.C. neighborhood of Spring Valley, an excavator swiveled slowly back and forth, the bucket scooping soil from one pile at the tent’s rear and depositing it in another mound closer to the roll-off container that would haul the dirt away. Sensors sipped the air, testing for traces of chemical weapons agents. Reina Wunschel stood to one side in her Tyvek hazmat suit, watching the soil cascade from the bucket. Toward the back of the tent, another ordnance technician watched the other pile. A third crew member worked the bucket on the excavator. In their suits and masks, it was difficult to tell them apart until Wunschel’s voice crackled over her radio, calling up the hill to the command center. “Can you zoom in?” she said. Outside the tent, it was a crisp March morning, with a forecast for afternoon snow. Inside the command trailer, Reina Wunschel’s husband Scott, the site manager for the Army’s