Victoria Pope

- 1989

Fellowship Title:

- Eastern Europe in the Era of Gorbachev

Fellowship Year:

- 1989

Gypsy Liberation In Hungary

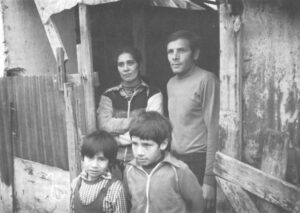

Text and Photos by Victoria Pope MISKOLC, Hungary–On streets without names, collapsed sheds circle the slag-heaps of the metal factory. Pigeons coo among the refuse. When dawn breaks, the wake-up sounds of coughing and coal-shoveling echo through the treeless hinterland. The gypsy community of Miskolc is waking up. Eva Gulyas is already dressed and combing her daughter’s hair when the two men arrive at her door. It is 7 am, but she offers the visitors shots of Barack, an Hungarian peach brandy. The men toss down the drink and Gulyas starts putting boots on her three year-old daughter. The boots are the right size for a child twice as big as the black-haired girl dangling her feet from a settee covered with torn cotton batting. A snow jacket goes on next. Its sleeves stop at the child’s elbows, and it is too small to zip up. “They say I need to pay a fine,” says Gulyas, pulling a dog-eared paper from the pocket of her parka. The men huddle over her and read it, taking

Little Food, Bad Water: The Tatters of Poland’s Rural Life

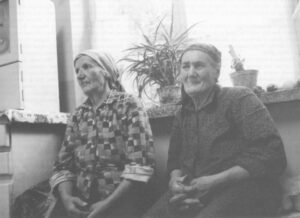

Text and Photos by Victoria Pope BOJARY, Poland–in this cluster of small villages near Bialystok, Poland, there is a funeral every month and a wedding every two years. The planting cycle, like the life cycle, is out of kilter. Though it’s harvest time, fields aren’t cut. Others tracts left fallow are overrun with wildflowers. Roads that should be abuzz with tractors are silent. Most all the local farmers are wasting their day in the gasoline line trying to buy fuel for their idle machines. Bojary’s main street is empty. The only immediate sign of life is the clothesline. It tells a story of poverty and old-age on the Polish farm. The clothes–rags really–are tatty and limp as they wag in the hot summer wind. Not even the blazing sun can bring form to them. Flesh-colored stockings with lead-colored streaks hang next to patched overalls, checkered handkerchiefs and black shirtwaists threadbare to a flat grey. There’s nothing frivolous, nothing new, and nothing for the young. About 40 percent of the Polish population still live in villages

Growing Up: Solidarity’s Turbulent Times

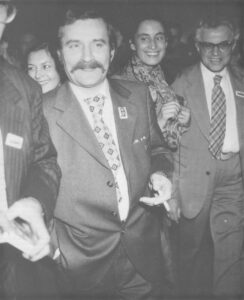

May 15-20, 1989: A week of highs and lows for Lech Walesa. In Strasbourg, France, the Council of Europe honors him with a human-rights award. In ceremonies there, he is accorded the protocol usually reserved for heads of state. Before Mass at the Strasbourg cathedral, the archbishop warmly greets the Solidarity trade union chief at the door. Then Walesa proceeds to Brussels, and meets with King Baudouin of Belgium. The talk barely gets underway when the awe-struck translator, a distinguished Polish intellectual, breaks down in tears. By the weekend Walesa is back in Poland, visiting the provincial city of Bydgoszcz. He leads a rally to bolster support for the local Solidarity candidates competing in Poland’s first partly free elections since World War II. Walesa meets with Solidarity members for a pep session. He enters the meeting hall of Bydgoszcz’s cable-manufacturing plant to the welcoming chant of “Lechu! Lechu!” But in the left-front corner of the room, a low rumble of voices turns into high-pitched cries of “Rulewski! Rulewski!” Clearly, Walesa hears the name of

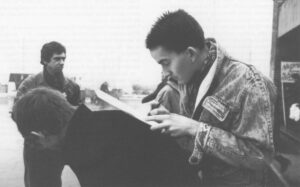

A Dam on the Danube: The Greening of Hungarian Politics

ESZTERGOM, Hungary–For more than 20 years, Istvan Horvath sifted and searched for Hungary’s buried treasures: ancient gold coins, altars, arches and urns. Were it not for the bulldozers on the banks of the Danube, he would have gone on digging peacefully for another two decades. Instead, he has excavated against a deadline to try and compress a century-load of work into five years. Those hovering bulldozers, and their role in building a hydroelectric dam on the Danube River at Nagymaros, near Esztergom, propelled the soft-spoken Horvath into opposition politics. The archaeologist and museum director pinned the blue and white button of the Danube Circle environmentalists to his coat lapel. On the double-height, Hapsburg-period door leading to his office he tacked up a poster declaring: “Stop Nagymaros.” Off-hours, Horvath wrote letters and essays repeating that conviction. Istvan Horvath. Not long ago, such partisan activities would have been out of the question for an employee of Hungary’s communist state bureaucracy. But over the last year, the authorities have espoused a new openness which has eased press censorship