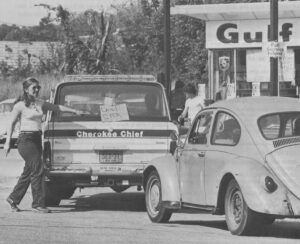

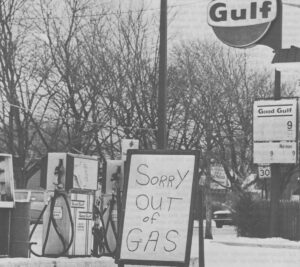

WASHINGTON, DC–While motorists waited in lines during the 1979 oil crisis, Mobil and Gulf made sharp cuts in gasoline allocations that were not consistent with their ample stocks of gasoline and crude oil, an unpublished government study shows.

WASHINGTON, DC–While motorists waited in lines during the 1979 oil crisis, Mobil and Gulf made sharp cuts in gasoline allocations that were not consistent with their ample stocks of gasoline and crude oil, an unpublished government study shows.

Department of Energy officials used a computer to analyze confidential company supply data and found that although Mobil and Gulf were not short of oil, they imposed gasoline allocation cutbacks similar to those of companies that were suffering shortages.

The study adds new information to the controversy over oil companies’ role in the crisis, which started with a temporary halt in Iranian oil exports and resulted in a doubling of world oil prices. Although the study does not impute motives to the companies, its findings add support to the arguments of critics who contend that industry actions during the crisis helped prolong the market panic that encouraged the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) to keep raising its prices.

Gulf and Mobil spokesmen criticized the study, calling it misleading. “It rehashes an old and discredited allegation that oil companies were withholding product,” a Mobil spokesman said.

A Gulf spokesman said: “We don’t think the study proves anything.”

Both companies said their overall gasoline sales for 1979 were higher than for the previous year, and they described their allocation cutbacks during the gas line months of May, June and July of 1979 as a prudent response to uncertain conditions.

The study was done in 1980 by DOE’s Office of Special Counsel, the office responsible for enforcing price and allocation rules. The study was not released, but a copy was obtained under the Freedom of Information Act.

During the crisis, Mobil and Gulf issued statements suggesting they were struggling to cope with reduced supplies. Gulf called its foreign crude supplies “tighter than hell–tighter than 1978.” Actually Gulf’s crude imports into the United States for the first half of 1979 were 23.5 per cent higher than for the same period in 1978.

During the crisis, Mobil and Gulf issued statements suggesting they were struggling to cope with reduced supplies. Gulf called its foreign crude supplies “tighter than hell–tighter than 1978.” Actually Gulf’s crude imports into the United States for the first half of 1979 were 23.5 per cent higher than for the same period in 1978.

Mobil’s statements during the crisis stressed the problems the company faced as a result of temporarily losing its Iranian oil. “The result was a nine per cent reduction in our crude supplies,” the company said. In fact, Mobil was among the most successful companies in covering its Iranian crude oil losses with extra oil from other countries. Mobil’s crude imports for the first half of 1979 were 18.9 per cent above those in the first half of 1978.

The main question the study raises–whether companies’ supply reductions were justified–has been debated before, with companies and their critics finding different meanings in the same facts. Government figures show that during the crisis the industry maintained crude oil stocks well above minimum levels and built up gasoline stockpiles, although gasoline stocks normally are drawn down during the summer driving season.

To companies, that represented sound, conservative inventory management consistent with the uncertainty of the time. But to critics, the industry’s failure to release available supplies added substantially to the upward pressure on prices.

Previous government reports have taken contradictory positions. The Justice Department’s report on the crisis said industry inventory management had “no significant role” in the crisis, while the Energy Department’s official report attributed two-thirds of the shortage to inventory management.

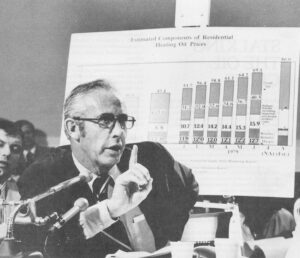

The allocation study is the first government analysis to become public that examines specific companies’ performance rather than using data for the whole industry. In a memo summing up the findings, then-DOE Special Counsel Paul Bloom, the agency’s chief enforcement official, said of Mobil and Gulf, “The analysis demonstrates that certain companies whose refinery activities were not significantly impacted by crude oil shortfalls nevertheless adjusted downward their allocation fractions in a manner similar to companies whose refinery activities were significantly impacted by crude oil shortfalls.

“The analysis does not thereby conclude that the former companies acted in violation of the regulations but does focus upon those companies whose actions warrant further investigation.”

Bloom sent the memo to then-Energy Secretary Charles Duncan, saying: “Because of the importance of this issue and its implications for enforcement actions, I think it appropriate to apprise you of the analysis and its results.”

Although Bloom would not comment and Duncan did not return calls, DOE sources said that Duncan did not answer the memo and that the “further investigation” recommended by Bloom never happened. The sources said Bloom, as an attorney in a prosecutorial job, held a more skeptical view of the companies than Duncan, a multimillionaire former corporation executive.

Mobil spokesman Allen Gray said: “I would expect that any prudent company, when a crisis hits, will tend to build inventories. Today it’s Iran shutting down–tomorrow it could be Saudi Arabia.”

Gulf spokesman Gerald Bradley acknowledged that the company had a good supply position during the crisis. “We were in pretty good shape,” he said. “We had ample crude, and we were running our refineries flat out.”

The computer analysis examined the gasoline allocation fractions used during 1979 by nine large oil companies. Companies used allocation fractions to calculate how much gasoline they made available each month to their gas stations.

After subtracting gasoline committed to state emergency reserves and government-designated hardship and priority users, the companies supplied their stations with a specified percentage of the gasoline supplied in the same month of the prior year. That percentage was called the allocation fraction. During May and June of 1979, the months of the worst gas lines, most companies had allocation fractions in the 75 to 85 per cent range.

The study used a statistical method called regression analysis to see whether companies’ allocation fractions were related to changes in inventories of gasoline and crude oil, the raw material from which gasoline is refined. In most cases, Bloom wrote, “each company that experienced significant crude oil shortfalls had an allocation fraction which was significantly and positively correlated with motor gasoline inventory.”

“In other words, the allocation fraction tended to increase when the motor gasoline inventory increased and tended to decrease when the motor gasoline inventory decreased. This relationship makes sound economic sense.”

Referring to Mobil and Gulf, Bloom wrote: “Two companies whose refinery activities were not significantly impacted by crude oil shortfalls had allocation fraction levels which correlated significantly and strongly with the companies that experienced crude oil shortfalls. For these two companies…allocation fractions were not significantly correlated with any economic variable evaluated.” The explanation, he wrote, “cannot be developed on the basis of the data evaluated.”

Although Mobil and Gulf stressed problems and uncertainties in their statements during the crisis, they spoke of the period in more positive terms in their annual reports, which are read mainly by investors. Both companies’ reports emphasized that their total gasoline sales for 1979 exceeded those of 1978, and spokesmen repeated those statistics in their rebuttals of the Bloom report.

“The real story is that rather than squirreling product away, Mobil, despite suffering major losses in its worldwide crude position, did an outstanding job in 1979 by actually increasing product distribution in the U.S. compared to 1978,” said Gray of Mobil. The company also stressed that clumsy federal allocation rules had aggravated the gas lines, a point on which analysts generally agree. Gulf’s spokesman, Bradley, said the company decided in April to cut its allocation fraction because company officials worried that otherwise gasoline inventories could drop to “dangerously low” levels by summer because of high demand.

Although both companies’ total gasoline sales for 1979 were higher than those in 1978, they cut back sales during the period of the gas lines in May, June and July. Mobil’s allocation fraction dropped from 95 per cent in April to 80 for May and June, then rose to 85 for July. Gulf’s was at 100 per cent through April, then dropped to 90 in May and 75 in June and July.

The study discloses new information about various companies’ supply positions during the crisis. To distinguish between companies with comfortable supplies and those that were short, the study compared their 1979 inventory levels and imports to the average of their 1977 and 1978 figures so that any “significant distortions in the data of either year would be smoothed out.”

The comparison found that for Mobil, the nation’s second largest oil company, both crude imports and stocks for the first half of 1979 were comparable to those of the base period. Gulf, the sixth largest, held significantly higher crude inventories in both the first and second quarters. Shell, Texaco and Union (which sells the 76 brand), however, had significantly lower crude inventories during the first quarter. In the second quarter the companies with lower crude inventories were Chevron, Exxon and Shell.

The study also reported that Chevron and Texaco were particularly hard hit in the first half of 1979 by cutbacks in imports from Indonesia, one of the world’s major oil exporters. Chevron lost 38,000 barrels a day in the first quarter and 74,000 in the second. Texaco’s shortfalls from Indonesia were 27,000 in the first quarter and 67,000 in the second. The study does not explain why that happened, but other oil analysts say that Japan panicked because of its almost total dependence on oil imports, adopted an “oil at any price” strategy and succeeded in outbidding American companies for Indonesian oil that otherwise would have gone mostly to California–the first state to have gas lines.

©1982 Brian Donovan

Brian Donovan concludes his fellowship investigation of U.S. petroleum policies with this issue.