NEW BRUNSWICK, N.J.–New Jersey had a problem. A cancer-causing, radioactive substance was widespread in homes throughout the state, threatening the health of thousands of residents. While state officials initially worried that publicity could cause public panic, just the opposite has happened.

Two years later, they are confronting a surprisingly different problem–apathy. Many New Jersey residents have ignored a major health risk that is literally in their own backyards: radon gas that occurs naturally in uranium-containing rocks and soils and seeps into basements.

Public hysteria did erupt, however, when state officials tried to dispose of dirt containing radon-emitting industrial waste from an old luminescent paint factory. A government plan to mix the contaminated soil with regular dirt and dump it in an abandoned quarry near rural Vernon, N.J. drew threats of civil disobedience. Angry citizens successfully blocked the action.

Why did the public ignore government warnings about the dangers of high levels of natural radon, while panicking about what state experts saw as the insignificant threat of soil laced with low-level radioactive waste?

Understanding why experts and the public fail so frequently to agree on the nature of health risks is of growing concern to government officials, industry executives, academics, environmental activists and the news media.

Efforts to bridge the gap–studying how the public perceives risk and how best to explain it–have made risk communication a growing new field.

“The core of the problem is that the risks that kill people are often not the same as the risks that frighten and anger people,” said Dr. Peter Sandman, head of the Rutgers University environmental communication research program here. “Risk for the experts means how many people will die, but risk for the public means that plus a great deal more. Is it fair or unfair? Is it voluntary or coerced? Is it familiar or high-tech and exotic?”

“Geological radon has no villain. It’s God’s radon. It strikes people in their homes, traditionally safe turf,” said Sandman, whose group is studying differing reactions to the radon threats. “’The landfill radon problem was very different. There was a readily identified villain which the community felt was unfairly imposing a risk without even telling it, much less asking its permission.”

Not surprisingly, the motives and means of the parties involved in communicating risk can generate their own debate.

The interest in risk communication is propelled, in part, by highly publicized incidents over the past two decades that have fueled public fears about the risks posed by modern technology, from pesticides in ground water to toxic waste dumps.

During this time, scientific instruments made it possible to detect ever smaller amounts of chemicals in the water or air, but scientific uncertainty made it difficult to interpret what risk these levels posed. Meanwhile, the increasing prominence of lawsuits has often framed environmental risk questions in terms of guilt and innocence and led to the pursuit of black-and-white answers.

While many risk assessment experts believe the world today is safer than ever before, they say American society is being changed by a Chicken Little-type mentality. The American public has grown more concerned about risk, less willing to assume it, and less trusting in public and private institutions. Many blame the news media.

“How extraordinary! The richest, longest lived, best protected, most resourceful civilization, with the highest degree of insight into its own technology, is on its way to becoming the most frightened,” lamented political scientist Aaron Wildavsky in a 1979 article on public perception of risk.

More recently, Milton Russell, a former EPA assistant administrator, called for better efforts in risk communication, saying “real people are suffering and dying because they don’t know when to worry and when to calm down. They don’t know when to demand action to reduce risk and when to relax because the health risks are trivial or simply not there.”

But some environmentalists are highly skeptical of the new field. Ellen Silbergeld, a scientist with the Environmental Defense Fund, considers all the talk about improving risk communication merely a “shield for inaction”’ by regulators and polluters.

“One person’s risk communication may be another person’s propaganda. It’s a tough call,”’ said William W. Lowrance, director of the life science and public policy program at Rockefeller University and author of one of the first books on risk.

“It certainly is an effective legal device. Industry may put money into risk communication to dissolve community fury,” said Marcel LaFollette. a Massachusetts Institute of Technology journalism and science policy professor. But, she added, the pressure for better risk communication “came from the grassroots. My sense is that this has bubbled up from below.”’

Ideally, says Rutgers’ Sandman, risk communication includes the “effort to alert people to risks they are not taking seriously enough, the effort to reassure people over risks they are overreacting to” and the effort to open up discussions between different parties in risk controversies.

In practice, he and other academic proponents admit, there is a “bigger market for expertise in how to calm down the public. Some of that market is driven by the sense the public is inappropriately alarmed. Some is driven by the desire to get the public inappropriately reassured. Both are happening.”

Risk communication has prompted:

- A National Academy of Sciences panel on risk perception and communication that is expected to report later this year.

- An array of federal studies, including three dozen projects at the Environmental Protection Agency and research at the National Science Foundation. The interagency task force on cancer, heart and lung disease, a 14-agency panel chaired by EPA, has a working group on the role of government in risk communication.

- An abundance of publications including several books, the Journal of Communication, and MIT and Harvard University’s quarterly, Science, Technology, and Human Values.

- An academic growth industry. A new center for risk communication at Columbia University includes a network of 35 public and private groups. Carnegie-Mellon University received a $1.3 million federal grant in 1987 to set up a risk perception and communication research program. Rutgers’ environmental communication program began in 1986. A group at Tufts University is conducting case studies on environmental risk communication.

- Scrutiny of the media’s role in communicating risk. Georgetown University’s Institute for Health Policy Analysis has sponsored a half dozen workshops for scientists and the media on subjects from radon to AIDS.

- Interest among Washington-based environmental think-tanks. The Conservation Foundation has sponsored symposia and publications on risk communication. Resources for the Future has a new Center for Risk Management.

- Attempts to prepare for a number of federal and state occupational and community right-to-know laws that require the release of unprecedented amounts of complex data. A key deadline comes July 1 when federal Superfund legislation orders that detailed information be made available on chemical emissions from plants around the country. California is attempting to implement Proposition 65, a massive new law requiring warning labels on all products containing chemicals that pose a significant risk of cancer or reproductive problems.

- Global activities. Disasters like the 1986 Chernobyl nuclear power accident led the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development to sponsor a recent symposium in Paris on radiation risk communication. The Canadian government held a risk communication meeting in Ottawa last December.

Traditionally, the scientific and technical community has tended to view risk in concrete terms: how many people will die or become ill because of a given activity?

Some frustrated technical experts have taken the view that if the public and policy makers could just be made to understand risk numbers the way they do, more rational management of risk would result. They have sought to make risk more understandable to the public by comparing rare and often little understood risks of manmade activities like radiation and industrial chemicals to more common risks of everyday life.

“Comparisons can be useful. We are not born with an instinctive feeling for what a risk of one in a million per lifetime means,” argued Richard Wilson and E.A.C. Crouch of the Energy and Environmental Policy Center of Harvard University.

The comparative risk approach was adopted by the nuclear industry in the mid-1970’s in an effort to convince the public that nuclear power was safe.

A controversial reactor safety study published by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission in 1975 estimated, for example, that an individual’s chance per year of dying in a motor vehicle accident was 1 in 4,000, while that of being hit by lightning was 1 in 2 million and of being killed by a nuclear reactor accident, 1 in 5 billion.

Wilson, a physicist, has proposed several risk comparison approaches. In 1979. he compared various risks estimated to pose one chance in a million of death in any one year: smoking 1.4 cigarettes; spending 3 hours in a coal mine; one chest x-ray; living 5 years at site boundary of a typical nuclear power plant or 150 years within 20 miles; eating 100 charcoal-broiled steaks.

Last year, Wilson and Crouch published a new listing of commonplace risks in Science magazine that, roughly translated, estimated that the annual risk of death from smoking one pack a day of cigarettes was 1 in 300; of a motor vehicle accident, 1 in 4,100; of exposure to air pollution in the eastern U.S., 1 in 5,000; of drinking water with the EPA limit of a controversial cancer-causing chemical trichloroethylene, 1 in 500 million.

Some comparisons have focused on specific areas, such as food. A widely publicized 1987 risk comparison by Dr. Bruce Ames, a University of California biochemist, showed that the cancer-causing potential of chemicals naturally found in foods (such as aflatoxin in peanut butter) may be far more hazardous than industrial chemicals, such as the trace amounts in drinking water.

Risk comparisons tend to make similar points: that the common risks such as driving a car or sitting in the sun often are more dangerous than feared technologies; that natural hazards are often worse than manmade ones; and that some of the most controversial new technologies are safer than others already in place.

But critics have attacked some risk comparisons as simplistic and sometimes unscientific. They charge that comparisons often measure apples and oranges, selectively use information (the NRC study came under criticism for calculating only risk from immediate fatalities not delayed ones), fail to convey the degree of uncertainty involved and generally ignore other factors important to the public in comparing risk, such as the degree of choice involved.

The Environmental Defense Fund’s Silbergeld sees risk comparisons as an attempt to “market unacceptable risk.” She cites a New York judge’s remarks, after settling complicated Agent Orange liability cases in 1984, that juries in Brooklyn didn’t have any trouble understanding probability because they go to the race track frequently. “Usually the public is not in a state of confusion…,” she said.

Dr. Vincent Covello, who recently left the National Science Foundation’s risk assessment program to head the new Columbia center, said that “many of these attempts to compare a risk in question with the risk of daily life are a form of attempting to manipulate public opinion.”

In contrast to the numerical approach, social scientists study how society and individuals perceive risk. “If you want to communicate with the public, you have to take the public’s concerns seriously,” said Baruch Fischhoff, a member of the National Academy panel who recently joined the new risk center at Carnegie-Mellon.

He is one of a small group of researchers who over the past decade have explored what factors contribute to the public’s perception of risk. Earlier working with a private firm, Decision Research in Eugene, Ore., Fischhoff and colleagues Paul Slovic and Sarah Lichtenstein compared perceived risk for 30 activities and technologies among four groups.

While nuclear power was ranked riskiest by the League of Women Voters and college student participants, it ranked eighth among businessmen and number 20 by technical experts. All four groups ranked motor vehicles, handguns and smoking in their top five.

A later study on over 80 diverse hazards found that they could be grouped into dread and unknown risks. Those that were most dreaded (nuclear weapons and nuclear power scored highest) were characterized by perceived lack of control, catastrophic potential, fatal consequences, and inequitable risks and benefits. In the “unknown risk” category (chemical technologies scored highest here), hazards were generally unobservable and new, with the potential harmful effects delayed in time.

The Decision Research group found that the more dread or unknown the risk, the more the public wanted to see the risk reduced and subject to strict regulation.

Others, including Covello and Sandman, have expanded this work to include a laundry list of nearly two dozen factors used by the public in defining and evaluating risk. This includes:

Magnitude. People are more concerned about major accidents involving fatalities and injuries at one time, such as airline crashes, than the same number scattered over a longer time period, such as car accidents. They are more concerned about irreversible hazards, such as nuclear war, than reversible ones, such as smoking. Risk to future generations, such as genetic damage, increases concern.

Evidence. Concern increases if a risk is poorly understood, scientifically unknown, uncertain or delayed in its effects, such as the development of cancer following exposure to low doses of chemical. Human evidence is more persuasive than animal studies.

Personal choice. Voluntary risks are far more acceptable than imposed ones. Smoking began to move from acceptable to unacceptable in public places once there was evidence that sidestream smoke could be harmful to others. Risks under an individual’s direct control are less threatening. Drivers may recognize the general risks of an accident but believe that they can avoid one.

Not in my backyard. A risk that is closer to home, threatening one’s family, is more upsetting than more widespread risks shared by the world. The public questions activities that appear to offer an unfair distribution of risks and benefits; those living next to a nuclear waste site may not be the ones who originally benefited from the nuclear power, for example. When those at risk also benefit, the activity may be more acceptable.

Publicity. Media attention heightens concern, regardless of the numbers involved. News coverage often focuses on new health risks rather than old but important ones. A single major, well-publicized accident, like Chernobyl or Bhopal, has a permanent impact. Television makes the risk even more real and imbues some images, like the cooling towers at Three Mile Island, with powerful symbolism long after the accident occurs. People are more concerned if media coverage makes the victims identifiable, such as workers trapped in a mine, than about statistical, but unknown, victims. If children are specifically at risk, concern rises.

Who’s in charge? People are more concerned about situations where the risk managers are seen to lack trust and credibility than those where the institutions are well regarded. Manmade hazards are less acceptable than those caused by acts of nature or God. There has not been a mass exodus from California because of the threat of earthquakes. People don’t hold rallies to fight floods.

Rutgers’ Sandman defines risk as “the sum of hazard and outrage. The public pays too little attention to hazard; the experts pay absolutely no attention to outrage. Not surprisingly, they rank risks differently.”

National leadership on environmental risk communication is generally credited to William Ruckleshaus upon his return to Washington in 1983 for a second tour of duty as head of the EPA. The agency was in a shambles, suffering from serious problems brought on by early Reagan administration appointees.

Ruckleshaus separated EPA’s mandate into three aspects of risk: defining what is hazardous (risk assessment), deciding how to deal with it (risk management) and explaining the process to the concerned public (risk communication).

Ruckleshaus’ interest in risk and risk communication took hold among both political and career officials at EPA. His successor, Lee Thomas, commissioned an internal study by about 75 career EPA officials that ranked 31 environmental problems according to their cancer risk, non-cancer health risks, ecological effects and welfare effects, such as economic damage.

The study, released last year, showed major discrepancies between what the task force experts rated as major risks and the major program priorities at EPA. Instead, EPA’s efforts, largely dictated by Congress, seem more closely linked to public opinion.

A recent comparison of the study with public polls done by the Roper Organization suggested that the greatest differences involved hazardous waste and chemical plant accidents. They ranked medium to low in the EPA task force’s view but high in public opinion (and high as an EPA program under the Superfund legislation).

And while the experts ranked pesticides, radon and indoor air pollution, consumer product exposure, worker exposure to chemicals and global warming (ozone depletion) relatively high in risk, these areas appeared to be of medium/low public concern.

Hazardous waste provided the most dramatic example, noted Frederick Allen, associate director of EPA’s Office of Policy Analysis. The task force said that in certain areas hazardous waste does pose a very serious risk, but relatively few people live near enough to be directly affected. But there has been a groundswell of national concern about hazardous waste.

“It’s a real challenge to try and sort out whether we ought to do what the experts say is the most important or what people say is most important. What’s the balance?” said Allen.

In addition to government interest in risk communication, industry–also troubled by credibility problems–has seen its need.

Public mistrust literally can wipe out an industry. In many ways, the demise of the nuclear industry in the United States is a case of poor risk communication by a paternalistic–some would say arrogant–industry that sought to reassure the public that nuclear power was safe by publicly stating that an accident was impossible. Then the impossible happened.

The 1978 accident at Pennsylvania’s Three Mile Island turned out to be more of a public relations disaster than a health problem. Students of the TMI accident note that it was a classic case in which the industry handled everything wrong–the government, the media and the public.

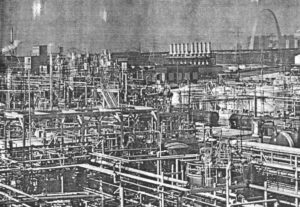

The chemical industry now is dealing with many of the problems faced earlier by the nuclear industry. A major challenge will come when new Superfund reporting requirements under the Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act of 1986 go into effect.

“During the next two years, a tidal wave of new information on hazardous chemicals will wash over thousands of communities across the United States,” warned Charles L. Elkins, director of EPA’s Office of Toxic Substances, in a recent EPA Journal. “The ‘wave’ will consist of reports to the public on the amount of hazardous chemicals stored in and released to the air, water and soil of those communities.” The first annual emissions reports from more than one million facilities must be submitted to EPA by July 1, 1988.

“How prepared are America’s communities to receive, understand, and act on this unprecedented deluge of information about hazardous chemicals?” asked Elkins. The answer, unfortunately, seems to be: Not very.”

A key question is how the chemical industry will handle it.

With the experiences of the nuclear industry in mind, many industry leaders “understand the consequences if they do not take it seriously,” said Covello.

There are worries that some companies will dump an abundance of information in the hope the public will throw up its hands, trying to meet their legal obligation in the least helpful way possible.

But the Chemical Manufacturers Association, a trade group, is conducting seminars for plant managers in preparation for Superfund. Included is a new manual by outside risk experts that cautions “risk communication, when properly done, is always better than stonewalling.”

The real testing ground for risk communication is at the local level. EPA has attempted a variety of risk communication experiments, starting under Ruckleshaus with an arsenic-emitting copper smelter in Tacoma, Washington in 1983 and more recently in California’s silicon valley, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Denver.

The agency is funding risk communication research to alert the public about the serious health risks associated with indoor radon, an environmental problem for which EPA has no legal authority so solutions are largely dependent on individual action rather than regulatory efforts.

In New Jersey, a state still suffering from its reputation as a chemical cancer alley, government officials are struggling to put environmental risk–both natural and manmade–in perspective. They have set up a risk communication unit and asked for outside advice.

Rutger’s Billie Jo Hance, Caron Chess and Sandman have just completed for the N.J. Department of Environmental Protection an 80-page manual for government called “Improving Dialogue with Communities.”

The Rutgers’ advice: “Pay as much attention to outrage factors, and to the community’s concerns, as to scientific variables. At the same time, don’t underestimate the public’s ability to understand the science.”

In the case of radon, environmental officials across the nation face the challenge of alerting the public to a risk that they must do something about. EPA’s Ann Fisher said that a variety of federal and state radon risk communication projects had already been undertaken in New York, Maryland, Maine, Florida, Pennsylvania, Colorado and New Jersey.

Radon is a big environmental health threat. Federal government estimates suggest that 5 to 20,000 lung cancer deaths may result each year in the United States from long-term exposure to geological radon. In northern N.J. alone, perhaps one in three homes has elevated radon levels sufficient to warrant remedial action under EPA guidelines.

Yet, it requires personal initiative to get one’s home tested to see if there is indeed a problem. And then, it requires further action–and money–to seek professional help in lowering the radon levels in the affected home.

Two 1986 surveys by Rutgers psychologist Neil Weinstein and Sandman for the state found, said Sandman, “that the majority of the people, including those in high-risk areas, were aware of radon, knew what the risk was and were not inclined to do anything about it. We did not find ignorance. We found apathy.”

The surveys found unwarranted optimism among individuals that downplayed their own risk from radon. And even among those who did have their homes tested, there was not a strong relationship between how much radon they found and how likely the homeowners were to take remedial action.

“We’re looking for ways to explain radon levels more effectively so that those with high levels decide to take action and those with low numbers relax,” said Sandman.

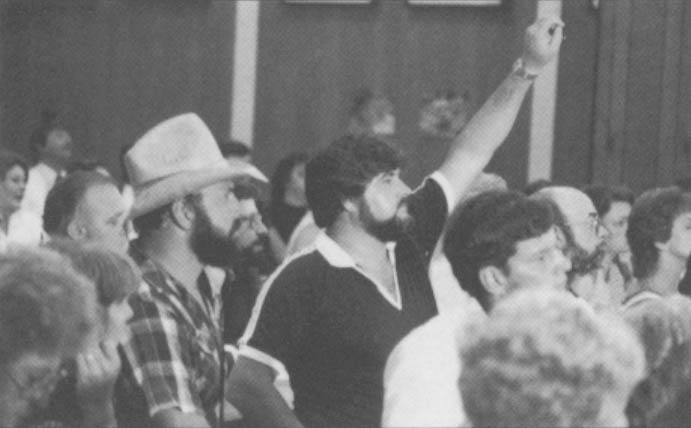

A recent case study by Rutgers’ Chess and Hance for the EPA compared different reactions to natural and manmade radon in three communities: Boyertown, Pa., which in December, 1984 became the first highly publicized geological radon hot spot in the country; Clinton, N.J., the first major geological radon hot spot in N.J. in 1986; and Vernon, N.J., where residents fought the state in 1986 against dumping low levels of radon from industrial waste.

“The real irony in Vernon is that residents protesting the disposal of manmade radon were potentially at higher risk from naturally occurring radon in their homes. It’s extremely likely the majority of protesters had not taken action to test for natural radon. So the obvious question is why?” asked Chess.

Her study suggests, once again, that the public viewed manmade risks differently than natural ones and that the state officials handled the situations very differently. They worked closely, and successfully, with Clinton town officials and citizens in dealing with natural radon, where they agreed there was a potentially serious health risk.

But the white hats they wore in Clinton became black hats in Vernon. Because the state viewed the risk of the radon-contaminated landfill as negligible, it did not take the community concerns seriously or involve them in the decision, said Chess. Predictably, “the result was a government nightmare, precipitating a public meeting of about 3,000 people, a rally of 10,000, a demonstration at the governor’s mansion and civil disobedience training,” she said.

New Jersey “is ahead of the federal government and any other state government in taking risk communication seriously,” Sandman said. But, he cautioned, “I also think it’s dragging its heels.” To listen to the public is “a very difficult transition for a government agency to make.”

©1988 Cristine Russell

Cristine Russell, on leave from The Washington Post, is reporting on the risks of lifestyle, work and environment.