Gamal Rasmi slumped into his chair and glanced about the dance floor, his fingers tapping a nervous beat on the table top. The Playboy Disco, one of Cairo’s most popular night spots, was nearly full but he recognized not a soul. “I used to know everyone here, absolutely everyone,” he said with a sigh, signaling the waiter for a German beer. The waiter didn’t see him and hurried by to fill another order. The music grew louder. Gamal’s fingers moved faster. “This getting married in Cairo, it may be a very stupid thing I am about to do,” he said. “I may never be able to dance again.”

Until recently, Gamal had come to the Playboy almost every evening to dance and drink a beer or two, acting out his fantasy that he was John Travolta in the movie, “Saturday Night Fever.” Then trauma entered his life: He got engaged. His fiancée Manell was a plump, silent woman who spent her time watching TV. She was also a born-again Muslim who recently had started “veiling” and she did not approve of dancing or alcoholic beverages. Gamal, a 28-year-old college graduate, was a bit nervous about this turn of events but as an unspoken concession to Manell, he had begun praying five times a day, for the first time in his life.

What particularly worried Gamal about getting married was the cost involved, for the $175 he earned a month as a driver for an American company didn’t give him much margin as it was. First he could not marry, or even spend time alone with Manell, until he had a fully furnished condominium. Then he would have to make a substantial payment in gold to her parents. And finally, there was the lesson of his father, who divided his time between Egypt and Saudi Arabia as a car salesman and was supporting four wives, an acceptable arrangement in Islam as long as he remained financially responsible for them all. Gamal swore that he intended to have only one wife, but just to cover himself, he had written into his marriage contract that if he ever divorced Manell, he would owe her only twenty cents.

Gamal, still wanting his beer, signaled for the waiter again. The club was dark and the light of candles on each small table bounced off the faces of young Egyptian couples. They wore smart Western attire and their conversations slipped easily in and out of Arabic, English and French. The disco music had reached torture levels of intensity, and Gamal could stand it no more. “Do you want to see me dance?” he asked, and without waiting for a reply, he was up and strutting across the dance floor, alone, arms pumping, head back, lost in the flashing lights and memories of his fading bachelor days. He was a man torn, like the Arab world itself, between two forces–the traditional, conservative Islamic values passed down through the centuries and the modern, liberal temptations of Western ways imported from an alien culture thousands of miles away.

The resultant clash of cultures is hardly a new phenomenon in the developing world, yet few people have found it more unsettling than the Arabs. For them, far more than for most, the future is rooted in the past–in their own unique and rich heritage, in their belief that what Mohammed the Prophet taught 13 centuries ago is a precise guide for today’s life–and when their children would rather watch Dallas than go to the mosque, when Nike sneakers and a greed for material things become as important as prayer beads and a need for spiritual fulfillment, then the very foundation of their Arabness is challenged and shaken.

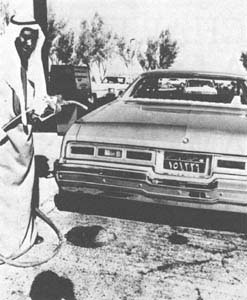

“Nobody was ready for all the money that descended on us during the oil boom of the ’70s,” Bahrain’s minister of development, Youssef Shirawi, told me as we sipped sweet tea in his office. “In having to choose, we accepted the manifestations of a modern, Western civilization, but refused its rulings. We accepted technology, for instance, but not science. People became confused, and they ran away to find comfort in Islam.”

What the Arabs wanted to do with their petrodollars was to import Western technology without sacrificing their Eastern culture. But Western technology brings with it Western culture, and the accumulation of wealth and possessions can become a religion in itself. The Arabs saw their world changing, and it scared them. They responded as have so many others in times of crisis: They turned to religion, heeding the muezzins’ call that summoned the multitudes with a promise of hope:

God is great.

I testify that there is no God but one God.

I testify that Mohammed is His Prophet.

Come to prayers.

Come to success.

God is great.

No God but one God.

The call to prayer offered a return to simpler, less threatening times, Those who abided strictly by the revelations Mohammed received while in a trance from the angel Gabriel, would be rewarded with a “perfect” life. There would be no need to question. Every event, every turn of one’s life, would be determined by God. Inshallah. If Allah wills it. Tell an Arab friend that you will see him tomorrow or wish him a safe journey or say that you hope his business meeting goes well, and the reply is always the same–inshallah.

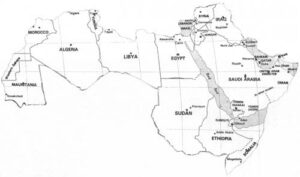

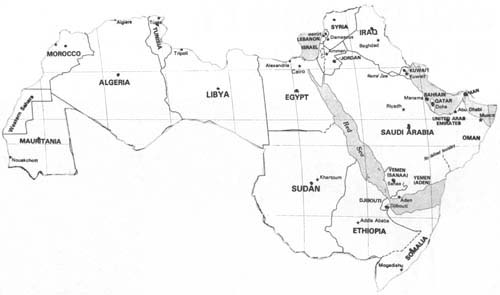

In many ways, the Arab world today is a religious empire. It encompasses eighteen countries and 4.6 million square miles, an area 25 percent larger than the United States. The largest country, Sudan, is more than three times the size of Texas; the smallest, Bahrain would fit neatly inside the boundaries of New York City. Except for a dying generation of Jews and a relative handful of Christians, virtually all the 167 million people in the Arab world are Muslims.

Many Westerners tend to think of the Arabs as a cohesive unit, and linguistically, culturally and religiously, they are to a large extent. Yet in political and human terms, their empire is a fractured and diverse one. The Saudis and Moroccans, for instance, are separated at the extreme by 4,500 miles and speak dialects that are mutually incomprehensible. The Tunisians eat cous cous (steamed semolina with meat and vegetables), the Egyptians prefer rice. In Iraq, 70 percent of the people are literate; in North Yemen, 88 percent are illiterate. A South Yemeni has a per capita income of $310 a year, a Qatari of $42,000. A Libyan lives in Africa, an Omani in Asia.

But the Arab believes these are superficial differences. He even views the bitter rivalries that divide the Arab nations into so-called moderate and radical camps as merely a temporary obstacle on the road to eventual Arab unity. Culture is a greater force than politics, he believes, and the strength of being Arab is in the heart. It is a sense of oneness among brethren, a bond born in the sharing of a desert history that goes back to the earliest days of mankind.

For the clan–or for the collection of clans that joined in the Arabian Peninsula many centuries ago to become tribes–desert survival was a daily challenge, and the character of today’s Arabs still carries the imprint of that challenge. The Arab needed to be tough to endure his environment and both strong and cunning to hold off raiding parties from other clans that preyed on the vulnerable. Unity was essential and so was the concept of strength in numbers. Conformity counted more than individuality. The desert–and the men who wandered there–were both feared and respected, and from the nomadic Bedouin came the roots of today’s Arab hospitality; any man, friend or foe, who had the courage and strength to cross the desert and appear at another’s tent was embraced as a brother for three days and given water, food, lodging. On the fourth day, he was on his own. The line between the kiss and the sword was a fine one.

“I shall always remember how I was humbled by those illiterate herdsmen who possessed, in so much greater measure than I, generosity and courage, endurance, patience and light-hearted gallantry,” wrote Wilfred Thesiger after journeying across Saudi Arabia’s Empty Quarter in the 1940s. “Among no other people have I felt the same sense of personal inferiority.”

At the, core of being Arab is the language itself. Indeed, the most accepted definition of Arab to day is one who speaks Arabic. None other seems to work. The real Arab comes from the thirteen tribes of the Arabian Peninsula, but what of the millions who don’t? Most Arabs are Muslim, but what of the six million Egyptian Coptic Christians? A European lives in Europe, an Asian in Asia, but does an Arab live in Arabia? So after decades of fruitless debate among the Arabs themselves, Middle East scholars generally agree that an Arab is one who speaks Arabic, a Semitic language related to Hebrew.

Unlike romance languages, there is an almost complete lack of cognates, or words derived from recognizable roots, in Arabic. The sounds, scripts, numerals, twenty-eight-letter alphabet and vowel system are different, the tenses imprecise. Although more than 600 English words–including algebra, admiral (from amir al bahr, or prince of the sea), alcohol, assassin, cotton, magazine, traffic, tariff–have an Arabic derivation, Westerners usually have a frightful time mastering the language.

Consider the trouble they have just agreeing on the name of the Libyan leader, Moammar Kadafi. The Los Angeles Times spells it Kadafi, Newsweek doubles the “d” to spell Kaddafi; the New York Times substitutes “Q” for “K” and adds an “h” to make it Qadhafi; the U.S. government slips in another “a” to get Qadhaafi; the Christian Science Monitor drops the “h” and one “a” for Qaddafi; the Washington Post prefers Gadhafi, the Associated Press Khadafy. To set the record straight, in classical Arabic, it should be Qathafi.

Classical Arabic is the language of the Koran, the Muslim Holy Book, and thus is the word of God. And because it is divine, it can not change. It is already perfect. Every thought, every word man needs to deal with the 20th Century, is already there, recorded from Allah’s revelations to the illiterate merchant Mohammed in 610 AD.

The French not withstanding, no one attaches more importance to his language than the Arab. For him Arabic is more than a medium of conversation. It is an object of worship, an almost metaphysical force that draws man closer to God. In many schools children are taught not to reason and question but only to memorize, to file away the Koran verse by verse as though the mind were a computer floppy disc. Master Arabic, they are told, and the wisdom of the Koran is unlocked. Protect the purity of Arabic and God’s word remains forever unsullied. But if Arabic is allowed to develop, to become more contemporary, religious scholars fear that the Koran’s meaning will become blurred, that into the black-and-white Koranic interpretation of life will seep some gray.

Today these scholars have cause for concern. The pressures of modernity, of scientific discoveries, of Western culture are confronting Arabic’s ability to absorb and grow as a living language. How, for instance should Arabic accommodate the word sandwich, something that wasn’t around in Mohammed’s time? How about television, automobile and the thousands of scientific, medical and mathematical terms that have crept into contemporary vocabularies of every language? Libya’s Kadafi has confronted the problem by banning all words that do not have an Arabic derivation. No one, for example, calls a Peugeot a Peugeot in Libya anymore; they call the French-made car a hamman, the Arabic word for pigeon.

In colloquial Arabic, which the classical purists dismiss as a low-level spoken language without fixed rules, the media and the public have adopted foreign words.

Sandwich in Egypt is sandawitshat, television is tilivizyoon, bus is autubiis, radio is radio. To the purists this is another nettlesome encroachment of Western culture, and the fifty-four scholars at the Egyptian Language Academy have worked long hours in recent years to find words in the Koran that describe all that has changed in 1,300 years. For sandwich, they came up with a term that translated as “a divider and a divided thing together with something fresh inside.” For automobile, their alternative was “that which goes by itself,” because self-propelled is a construction that does not exist in Arabic.

Predictably, no one says that he is taking a “that which goes by itself” to find a cheese “divider and a divided thing together with something fresh inside.” He gets into an autubiis and buys a cheese sandawitshat. The offerings of the academy, which at first were ridiculed, are now simply ignored. Its members are making such slow progress that only now are they searching for words to define medical and scientific discoveries and innovations made by the West in 1970.

No one suggests that classical Arabic, so rich in imagery and vocabulary, will join Latin in the graveyard of dead languages–the importance of the Koran in daily life negates that possibility–but the pace of the academy’s work does seem to indicate that classical Arabic, like the very heart of Arabia, will remain married to the past, useful primarily as a medium for religious and intellectual discussions.

“The theory of knowledge for Arab Muslims is different than that in the West,” Hussein Amin, an Egyptian writer on Islamic affairs told me. “With you, knowledge is the means to conquer the unknown. With us, it is a collection of material embodied in books which you can possess by reading-and the older the books, the better. True Muslims believe that what Mohammed left is perfect for all countries and all times, so developing Islam is out of the question. It’s a concept the people in the West have a hard time understanding.”

The prevailing Western perception of the Arab was captured not long ago in a political cartoon in a Boston newspaper. It showed a Muslim kneeling in prayer and over his head, in heavy black letters, was a single word: HATE! Once Jews, blacks and other minorities were subjected to similar degradation; today only the Arabs are still fair game, primarily, I think, because unlike most other peoples of the developing world, they have refused to fully assimilate Western ways or capitulate to Western values. Thus they are seen as a threat and, armed with oil and the ability to make war or peace with Israel, they are in a position to translate that threat into actions that affect Americans and Europeans. The West feels comfortable with Israel because Israelis are perceived to be Europeans; it accepts the African or Indian who dresses, thinks and acts like a Westerner. But the Arab remains always the Arab, a man held hostage by religion and culturally obsessed with identity.

His faith is more than a religion; it is a complete way of life, for Islam and the forces of society are in constant interplay. Islam is politics, law, social behavior and so exacting in detail that Mohammed even offers the proper positions for sexual intercourse. Allah is reached through knowledge and faith, intellect and will, and every man communicates directly with his God, rather than using priests as intermediaries. Says Libya’s Kadafi, “The solution to all human problems is Islam.”

Taken to the extreme–as almost everything is in the Middle East–I found this widely shared sentiment troublesome. It can be a detriment to progress because for the orthodox, coping with modernity does not require intellectual development or imaginative solutions. Only faith is necessary. Inshallah. Indeed, in Islamic institutions, the very word innovation in heresy, because nothing can be new; all knowledge is already in the Koran. To follow the familiar path is best. (The practices of Mohammed are known as the Sunna, meaning “the road.”) Even modern science is viewed as something of an atheistic tool, which perhaps helps explain why some of Saudi Arabia’s old-time religious leaders still insist the world is flat.

New ideas, though, eventually become a powerful force in themselves, perhaps a greater force than organized religion. Whether it is in the United States or the Arab world, the strength of the Moral Majority ebbs and flows, the attraction of religion swings like a pendulum. One may cling tenaciously to the past, but change becomes inevitable and the smell of it in the wind is irresistible, especially to the young. Just consider that less than a generation ago, Saudi Arabia’s school enrollment totaled 30,000. Now there are 2 million Saudis in schools and universities.

It is easy to forget how far many Arabs have already traveled in three decades, moving from illiteracy to video in a single step, from a primitive Bedouin society in the Arabian Peninsula to one that has sent a 29-year-old Saudi prince into space on the U.S. shuttle Discovery as the first Arab astronaut. However disturbing it is to some traditionalists, the clash of cultures from East and West is slowly becoming a marriage of cultures in the Arab world, and young, educated Arabs are nudging their countries into the mainstream of the world community.

“We can see a future role for ourselves in the world,” says Saudi’s astronaut-prince, Sultan iban Salman al Saud. “Not to compete, but to contribute.”

©1986 David Lamb

David Lamb, a reporter on leave from The Los Angeles Times, is chronicling the Arabs today.