Text and photos by Donna DeCesare

“The weak one is the one society thinks is good, but that’s the one that is going to end up dead.”

–Angel, Latina gang member

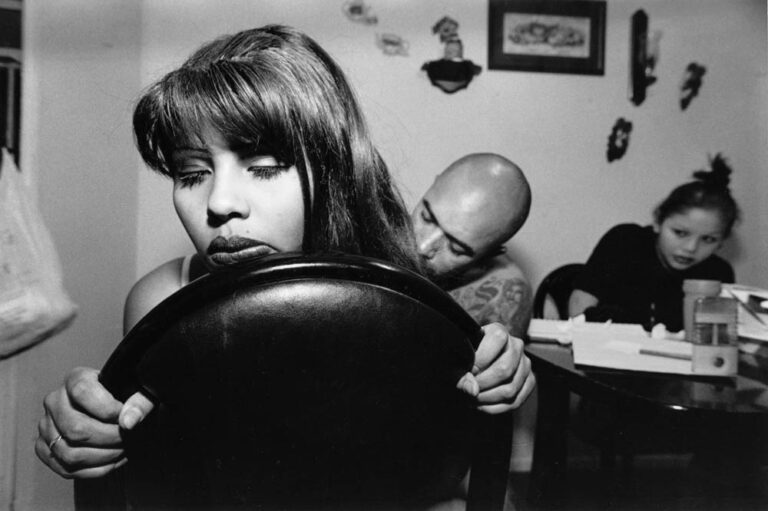

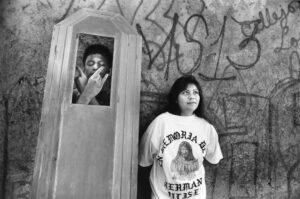

Los Angeles — “Call me Angel,” she said evenly, meeting my gaze. A faint scent of wet Pampers clings to her knit top after she places her toddler, Tonio, in blankets on the floor. Sinking heavily into a black Naugahyde couch, she begins. “It was supposed to be a kickback for us homegirls, a slumber party.” I watch her “fangs” — those gravity-defying teased bangs favored by Latinas of a certain age — casting bird nest shadows on the mildew-stained wall as she speaks. Angel remembers waiting at the house with Dreamer while the other homegirls made a beer run. “There was a knock at the door. I got up thinking — ‘gotta be the homegirls,’ but before I know what’s up, my best friend Dreamer is yelling at me: ‘Look, I’m the oldest, you get under the bed and stay there.’ So I did it,” Angel continues

From her hiding place, heart pounding, eyes tightly shut, she could hear a familiar girl’s voice screaming, “You bitch,” then a blast of gunfire followed by a terrible silence. “I was thinking, ‘Oh no, she’s not dead. This ain’t real,’” Angel trembles, rocking herself. “When I felt it was safe to come out, I found my best friend. You couldn’t even see her face. You know, it was like they shooted her so much you couldn’t even describe how she was.”

When police arrived, Angel told them about the girl who’d been sending Dreamer messages on loose leaf paper with the number 187 written in blood. (A ‘187’ is L.A. police code for a homicide; in gang parlance it’s a death threat.) Angel hadn’t glimpsed the murderer’s face, but she felt certain it was the same girl — a rival gang member who’d been jilted by one of her own homeboys and turned jealous when he began dating Dreamer. “My friend Dreamer kept saying she was going to die,” she told the cops, sobbing. “I didn’t believe her.”

The cops on the case didn’t believe Angel would make a credible witness. Unable to talk about her feelings with her angry and terrified mom or with anyone besides her homeboys, Angel came to a bitter conclusion: “ The cops weren’t going to make that girl pay for the murder of my best friend. The way I saw it, the only person who was going to make her pay — it was me. My homeboys were telling me: ‘Don’t do it. Let us do it. You’re twelve. That’s too young.’ But I was like, ‘ No, that was my best friend. She’s going to pay and I’m going to take her badge.

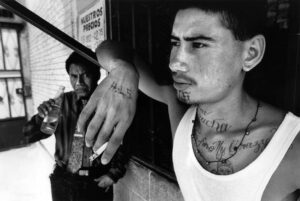

The conclusion of this story is grim, not unusual. Even as homicide rates have fallen nationally, the proportion of L.A. homicides that are gang related has doubled since 1980, now accounting for 40 per cent of all murders. That California’s skyrocketing incarceration rates, which are now the nation’s second highest, have had no apparent effect is especially alarming. Young Californians live in a state with 18 times as many gun stores as McDonalds restaurants — and in a nation with fewer federal safety regulations for guns than for teddy bears.

In the brutal world of LA gangs, youths view justice as a “do-it-yourself” project. Most of the mayhem occurs among teenagers over turf, status or revenge. Kids like Angel, from the housing projects, or kids from poor residential tracts, are growing up alone. They are neglected, feared or shunned by their fragmented communities and their own troubled parents. No one tried to stop Angel as she plotted the payback — no parent, no counselor, no teacher. Left to the company of her peers and the vigilante code of streets, where guns are readily available, Angel disguised herself as a boy and got away with murder.

Holding her head in her hands, nearly a decade later, Angel’s voice grows quiet.

“Even though I did it in a good cause — killing her because she killed my best friend — It wasn’t on me to let her pay for it. I should of let God take care of it.” She looks up, wiping her tear-streaked face. “Now I think about that girl’s mom or whoever was with her. I think about how they are…I’m scared. I still have to deal with it every day of my life. When you take somebody’s life you can’t pay it. Even if you kill yourself, you can’t pay it. It’s not possible.”

Media outlets have recently developed a fascination with girl gangsters who kill. But this fascination has more to do with our society’s fear of violent crime and its need to justify current crackdown policies, than with the realities of gang girl’s lives, according to Dr. Meda Chesney-Lind, a sociologist who has been studying girls in the criminal justice system for more than 20 years. The fearsome image of marauding girls swelling the ranks of the 150,000 gun-toting gang members, roaming L.A. streets and shopping malls, ever ready to steal, kill and die for their gang, remains as ubiquitous as it is inaccurate. For Chesney-Lind, it amounts to a criminal version of the madonna/whore complex. “We either ignore women’s violence entirely or we demonize it,” she said.

Chesney-Lind admits that girls may be more numerous and that FBI data indicate a significant increase in the number of girls arrested for violent crimes. However, she argues such facts are largely irrelevant to the question of whether girls are becoming more violent. Chesney-Lind points out that FBI data show that roughly 10 per cent of youth arrested for violent crime are girls, and that this percentage has been constant for decades. Motivating factors for girls joining gangs are similar to those who become runaways or street kids. “It’s still abuse, sexual abuse, and economic marginalization,” she said.

Criminologists know that that the criminal careers of most youthful offenders last only one year and that more than 80 per cent of those who commit a violent offense during adolescence mature out of such behavior by age 21. Girls age out of gangs faster than boys in part because of motherhood, according to Chesney-Lind. “Having a child forces you to change your relationships, expectations and responsibilities,” she notes.

Chesney-Lind sees a selfishness in the baby boomer generation’s policies toward youth. An assessment of youth oriented anti-crime programs conducted for the American Youth Policy Forum concludes that programs that provide individual attention from caring adults significantly reduce youth violence. “We know what kids need, yet we’re dismantling family courts and trying juvenile offenders as adults. Girls face a society that is getting meaner,” she said.

Most of the homegirls I met recently in L.A. seemed more vulnerable than mean. The tendency toward absolute judgment and vengeful remedies are hallmarks of adolescence that are enshrined in gang culture. But a combination of motherhood, maturation and supportive programs helped many of those I’ve talked with. Jessica Diaz, Mirna Solorzano and Herika Hernandez each followed a different path toward change.

I first met Jessica Diaz three years ago at the Ventura Training School, the only juvenile correctional facility in California that holds girls.

At fourteen, addled by an addiction to crack, she’d been persuaded to help her drug dealer rob a bank. “He said with the money, we could go away somewhere else. I hated my life. I wanted to escape as far away as I could, ” Jessica said, smiling at her foolhardiness.

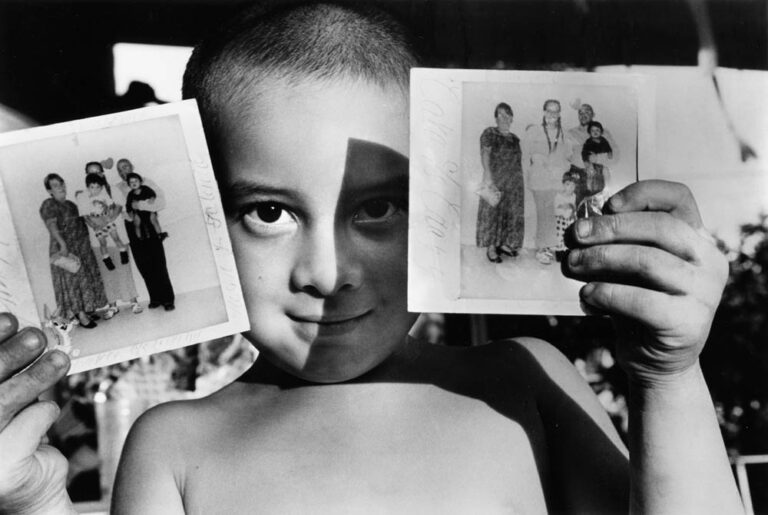

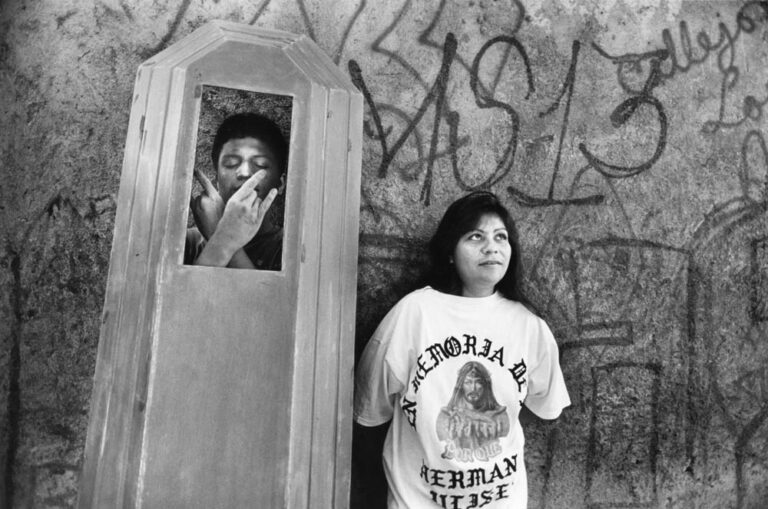

As I learned more about her early life, such folly became understandable. From the window of their tiny house in El Salvador, three year old Jessica had watched as government soldiers took her father outside and shot him in the head. Years later in L.A., she and her brothers, Victor and Ulises, would run horrified as a gun battle with the Eighteenth Street gang mowed down their friends. That the three Diaz kids became Mara Salvatrucha gang members seems as unsurprising as the tragic fact that Jessica’s brothers are now dead.

“I hated being locked up, but for me in a way it was like going away to college.” Jessica said, remembering Ventura. She devoured books while she was there, thrillers, mysteries, romances. Her favorites were books by Sandra Cisneros and Luis Rodriguez — books about people like her. “I had a good psychology teacher who taught us parenting classes. It made me think a lot about me and my mom, about my family, and about how I wanted to raise my kids. I didn’t want to keep repeating the same negative patterns over and over, you know. And damn, suddenly I could see it when I did something I didn’t really want to do.”

But parole, at first, was a road of rejection. Her son Carlos, born just before her arrest, had bonded with her mother during her absence and refused to accept Jessica as his mother. She found looking for work demoralizing and humiliating. “Not many people want to give ex-cons a job,” she said, adding: “For a month I went back to the pipe…[crack].” But after locking her up for a few weeks to make a point, her parole officer helped her get a job at the Los Angeles Conservation Corp.

LACC is a visionary program that combines high school equivalency education and therapy with paid work on conservation or community improvement projects. For many former gang members, it creates a bond that replace their gang ties as well as providing their first experience of work. Her nine months at LACC were the bridge Jessica needed.

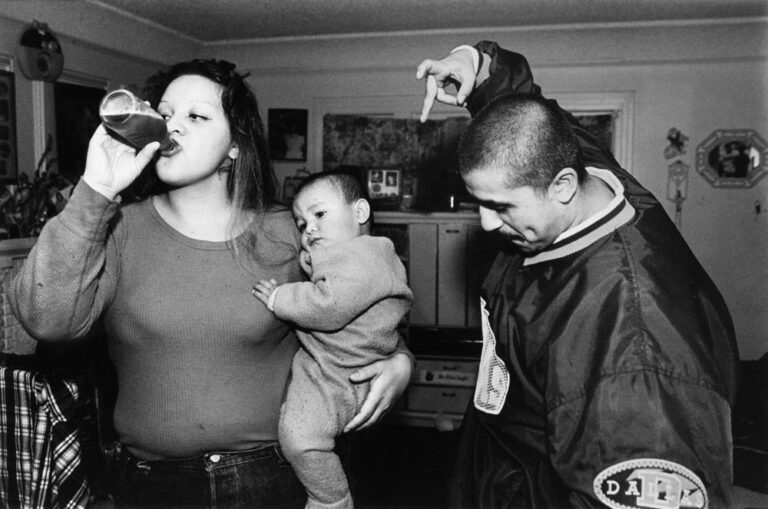

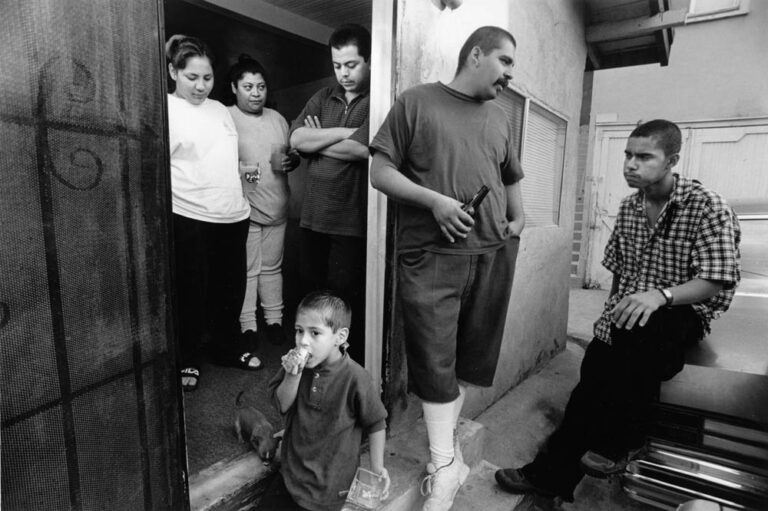

Since LACC, Jessica has become a wife and a mother again. For the moment, she is content being a homemaker in the working class enclave of Huntington Park, bonding with her daughter, Cassandra, that she missed with her son. She and Danny would like Carlos to live with them, but Jessica recognizes that building a relationship will take time. Gazing at her son’s photograph on the wall she said, “Carlos is all my mom has besides me, now that my brothers are gone. We can work it out.”

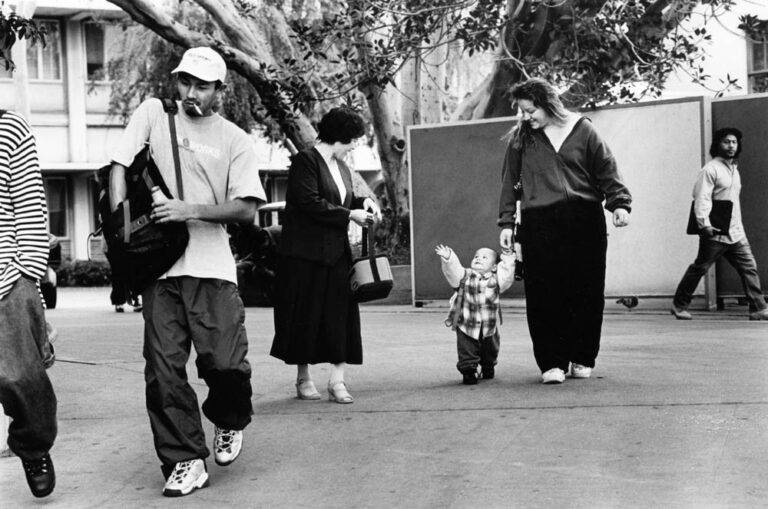

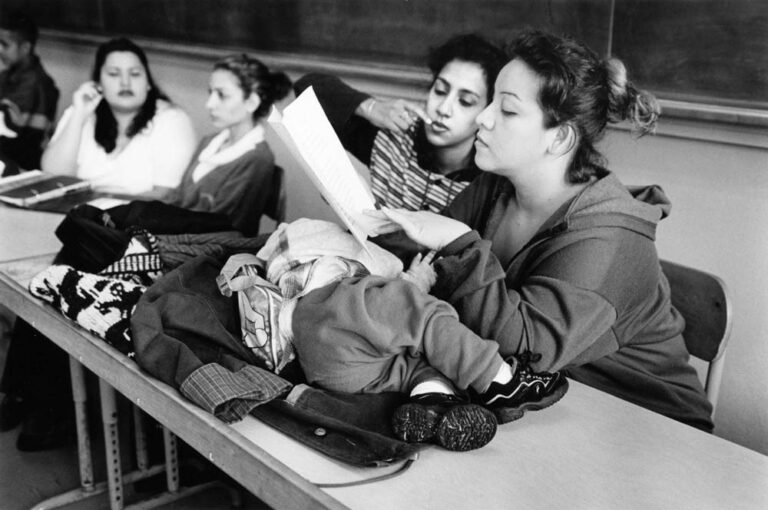

At 7:00 a.m., Mirna Solorzano rises and prepares her son, Edwin, for their daily trek from South Central Los Angeles to L.A. Community College.

While Mirna sits in English Lit. class, Edwin attends a special kindergarten enrichment program on campus. When she can afford it, two year old Nathan stays with a babysitter. By half past seven, the babysitter still hasn’t arrived. “We’d better go now,” Mirna said, throwing one last nervous glance at the clock. She slings her book bag over one shoulder, cradles Nathan on her hip and reaches for Edwin’s hand with her free hand, while closing the heavily grilled front door with her foot. The three will spend the next hour and a half snaking their way by bus through LA’s commuter traffic.

It’s a short journey compared to the one Mirna has traveled to become a student again. Her childhood home life had the intensity of a political movement. Mirna’s father was a trade union leader who’d fled death squads in El Salvador. From age five, when her family arrived in LA, she went to political rallies. “My parents were fighting to be free, for El Salvador to be free and all that, but it got to such an extreme that I hated the guerrillas they supported. I felt, ‘Why do I always have to be later on, later on,’” she said, gesturing her parents’ presumed dismissal of her with her hands. “ I wanted to go out, have fun.“

The “cause” eventually strained her parents’ fragile marriage. Mirna’s mother began an affair with a family friend who years later became Mirna’s stepfather. But when her mother was absent, the man made sexual advances. “I hated him and I hated my mother for believing him and not me,” she said heatedly, remembering what happened when she tried to tell mother about how he’d touched her. By fourteen, she was running away from home and attempting suicide.

Eighteenth Street gang crash pads became her refuge, and gangsters her guerrilla fighters. “My homeboys tried to kill him once because of what he did to me,” she said, referring to her stepfather.

It took a nervous breakdown and hospitalization at 18 to change Mirna’s course. Mirna credits her therapist and social worker for the transformation that has sent her back to school, helped her begin a reconcilation with her mother, and to develop a respectful relationship with her father. A recent NPR radio report about Homies Unidos, a youth program which is helping gang members in El Salvador, caught her attention. “I’m going to contact them about starting something like that here in LA.” Squeezing her son Edwin’s hand she adds, “But I won’t make the same mistake my parents made with me. My kids come before any program. I want them always to feel they can tell me the truth and can ask for what they need.”

At first glance, Herika Hernandez seems to have almost nothing in common with either Jessica Diaz or Mirna Solorzano except perhaps for her Salvadoran heritage. The poised tenth grader from Beverly Hills High has made honor roll consistently, was class president of her middle school and has her sights fixed on a career in law. But being so gifted can be a lonely experience for a teenager growing up in a housing project.

For years, Herika watched helplessly as her father humiliated and beat her mother when he came home in a drunken rage. Before her mother finally got the courage to leave, Herika began staying away from home. Her friends from school and the projects all had older brothers and sisters in gangs. By age eleven, Herika was wearing baggy pants and hanging with the Culver City gang. She knew that the gang would only bring trouble, but she was lonely, bored and desperate to escape tensions at home.

One of her teachers recognized what was happening and told her about the Fulfillment Fund mentoring program. The Fund is designed to help immigrant or poor kids of average or higher academic ability complete high school and set their sights on college. It makes a 10 year commitment to kids who join.

At first, Herika was worried about having a mentor. What could she talk about with someone so much older? But she liked Barbara Joy Laffy’s warm humor immediately. With Barbara Joy, Herika has been able to explore a cultural world far away from the projects where she lives, without the accustomed alienation she feels at home. “I love classical music,” Herika said after one of their outings. “It takes you places you’ve never been. My friends would think it’s weird if I told them. Someday they’ll understand.”

Or perhaps not. Last spring, as Herika’s fourteen year-old brother and three friends walked home from school, a car of gang members drove up and began blasting at them. The boys ran into an alley but one boy was killed and another injured. “My brother’s friend had just been jumped in [initiated into] the Culver City gang. The guys that shot were looking for him, but they killed another kid who wasn’t in the gang,” Herika recalled. Remembering how hard her mother took the news and the tensions it raised at home between her siblings, she added, “My mentor is like a second mother to me.”

In addition to Barbara Joy’s bimonthly outings with Herika, nurturing from the Fulfillment Fund staff and Herika’s own volunteer activities have been an anchor during her first difficult year at Beverly Hills High. Most of the student body are privileged, and Herika has found it hard to make friends. “If I say where I live they can see me as low class, like their maid’s daughter, like some alley cat that wandered into their house,” she said, frowning. “They might even be immigrants themselves — Persian or Asian or Lebanese — but they use the word as if it means Latinos.”

Now in her second year at the school, Herika has organized a tight group among the handful of Latino students. The collection of ninth through twelfth graders who gather for lunch each day are as diverse as a meeting of the Organization of American States. The daughter of a French diplomat, born in Peru, jokes with a handsome Guatemalan boy. They are greeted by a Mexican, a Salvadoran and an Ecuadoran. Over sandwiches, Taco Bell burritos and Cokes, with Herika holding court, they plot to form a Latino club on campus. The talk moves on to college plans, the Air Force and other future dreams.

I leave L.A. uncertain what the future will bring for Angel, Jessica, Mirna and Herika. Each in her own way is charting a future, each is trying to overcome the pitfalls of her past grief and turmoil. Each is trying to avoid the mistakes of her parent’s generation. All four will have to map their journey. But it is just as clear that for many girls, counselors, teachers, mentors, and job programs can be lifesavers in the storm of adolescence in the barrio.

© 1998 Donna DeCesare

Donna DeCesare, a New York freelance photographer, is investigating gang violence in the Americas.

![At the Haitian National Penitentiary, Touchè Caman does outreach for Chans Altenativ. looking for deportees among the inmates. “I never thought I’d be going back into a prison after the last time,” he tells me laughing. “It’s a lot different on the other side [of the bars]. “Maybe Chans Altenativ can help a few of them when they get out.”](https://aliciapatterson.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/DeCesare_Haiti01-300x204.jpg)