Text and photos by Donna DeCesare

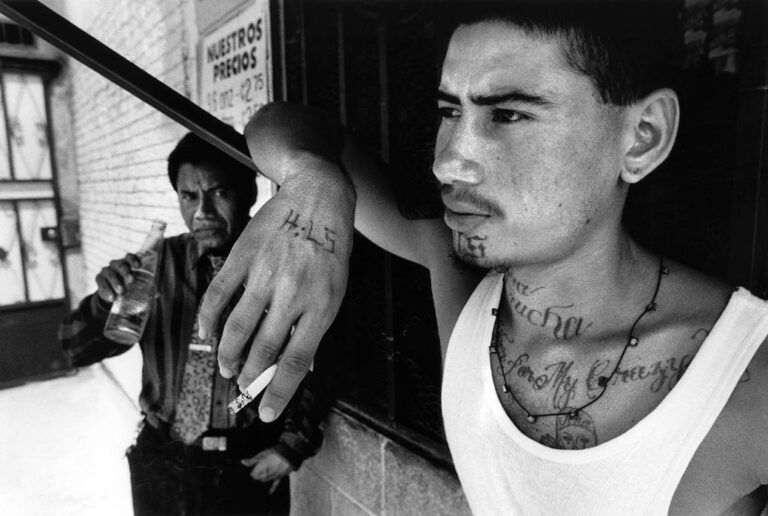

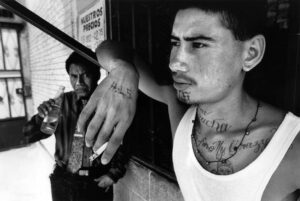

Soyapango, El Salvador — During pre-dusk hours when school children in crumpled uniforms race home, past the maquila factory workers wearily descending from buses, Shy Boy and his friends emerge alert and ready for business. They scatter in clusters around their cul-de-sac. Several move towards a grocery store, displaying their crop of gold chains and other “hot” items for interested buyers

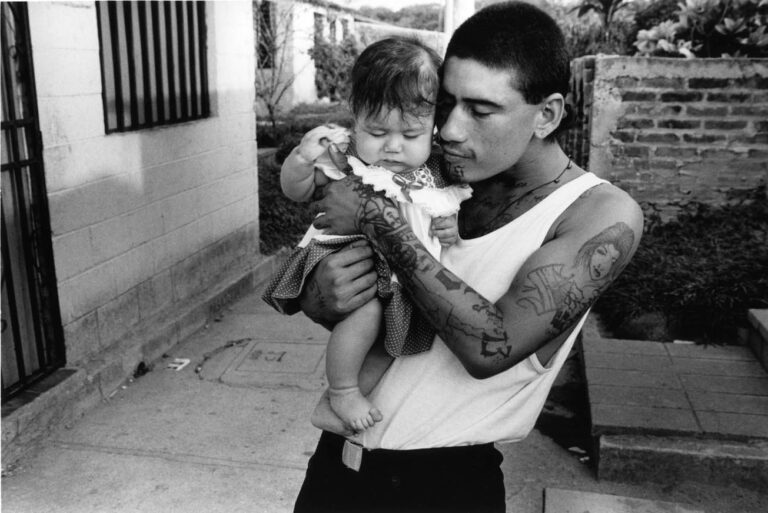

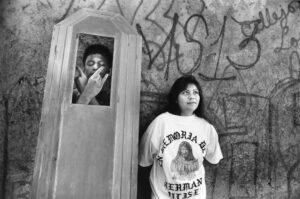

A middle-aged woman, with stern Indian features, balances a basket of fruit on her head as she glides past graffiti-sprayed walls. Three not-so-muscular youths in tight muscle shirts wave their tattooed arms wildly, throwing gang hand signs and flirting to grab her attention. Finally, she cracks a smile.

Wiping her hands on her stained, ruffled apron, she lowers her basket. The boys laugh as mango juice escapes from their lips. She laughs with them.

Shy Boy, aloof and elusive, takes in the scene. “People here think I’m the gang leader because I used to live in Los Angeles,” he says, almost wistfully. “But we don’t have leaders. I have respect from the homeboys, but I don’t tell other people what to do.”

This corner and the surrounding streets of this working class enclave are Big Gangsta Locos territory. About 30 youths belong to BGLS, a subgroup of the infamous Mara Salvatrucha, MS, gang of Los Angeles. Most of the youths are fifteen or sixteen-years-old. A few, like Shy Boy, who will soon turn nineteen, are older. While Shy Boy may not be the leader, it is clear from the way the others approach and quietly confer with him that his opinions are valued.

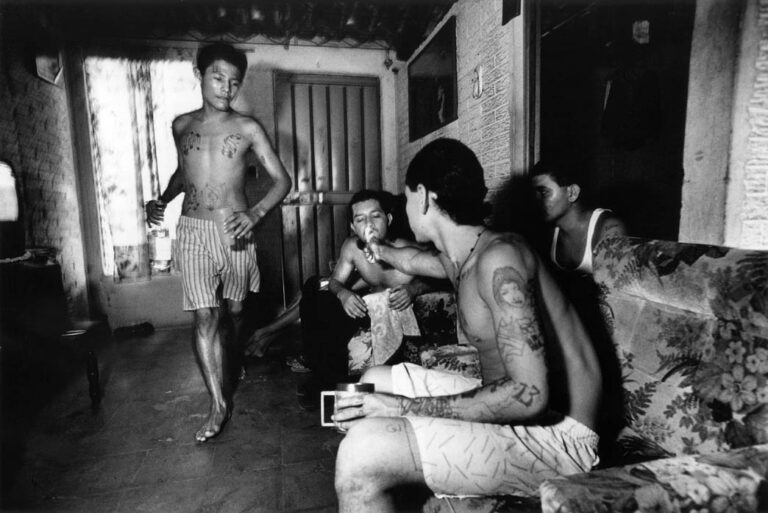

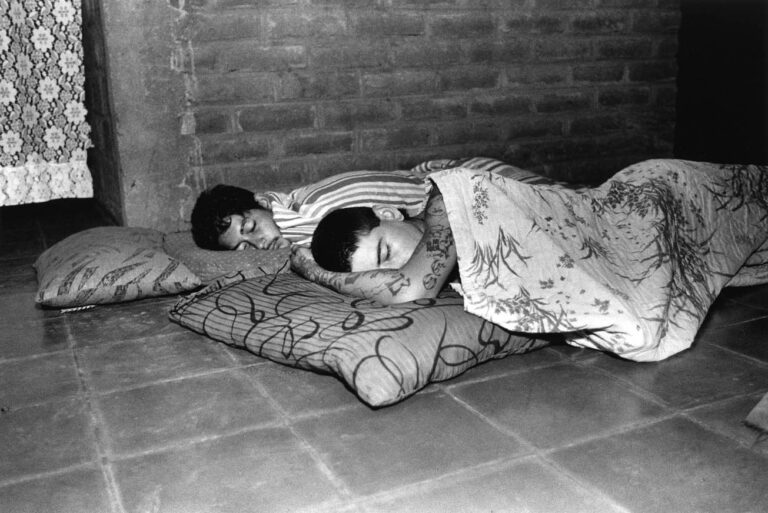

Tonight is a good night for the BGLS. Flash sold a couple of gold chains. Other homeboys add enough money to buy a round of pupusas, small corn pancakes stuffed with cheese and beans, now sizzling on an outdoor grill. The homeboys eat hungrily and the cook, a woman from the barrio, is happy to have made such a big sale so quickly.

As darkness falls, the homeboys begin to make their rounds, setting off in groups of twos or threes to check out who is on their turf. “We protect the people here from enemy gangs and thieves that would rob them,” Shy Boy says proudly. “We never steal from our own barrio. That is why we get along with people here.”

It is true that many people stop to chat or joke with the youths as they saunter along. But just as many tense or clutch their children, not daring to look at the tattooed faces as they hurry past. More than one resentful gaze from a small group of men follow them as the youths progress down a lane.

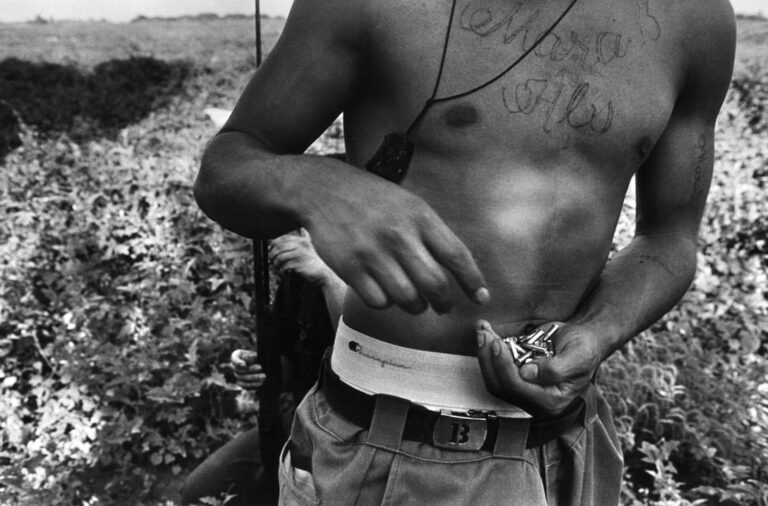

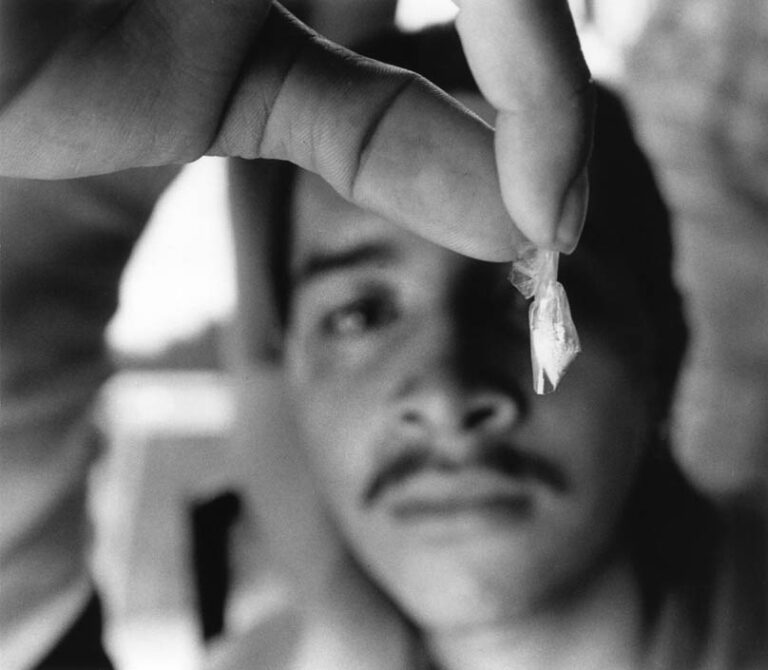

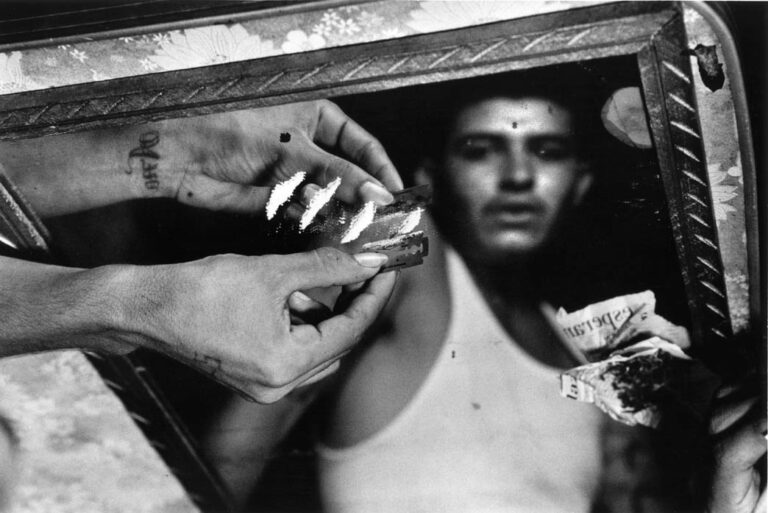

Two blocks away, a foot patrol of policemen stop and briskly frisk Shy Boy, Flash and Scrappy. They demand identification papers, which none of the youths have. Finding neither drugs nor weapons, they let the boys go with an angry warning to go home and stay out of trouble. “They’re not doing anything right now,” a cop remarks to no one in particular. “But when they get drunk and drugged, they are a plague on these streets.”

Shy Boy agrees that the homeboys often do get into street fights when they are drunk or stoned. He recently lost use of three fingers when a neighborhood drunk (not a gang member) slashed his arm with a machete and attacked Scrappy with several deep gashes to his head. “We were really high, so we didn’t even know what was happening.” Shy Boy recalls. “I guess it’s a miracle that we are still alive.”

Indeed, it is no small miracle. Pan American Health Organization statistics place El Salvador’s homicide rate highest in the hemisphere, surpassing even Colombia. Moreover, the reports indicate that the violence in El Salvador is now much greater than during the 1980s, when civil war grabbed international headlines

Police reports cite organized criminal rings, increased drug-trafficking, disgruntled ex-soldiers or ex-guerrillas who have become bandits, and growing numbers of deported gang members from the United States as factors in the violent crime surge. Youth gang membership is growing alarmingly, with estimates that as many as 10,000 youths nationwide may belong to gangs. No one in El Salvador appears to know how much crime is committed by each group.

A new computerized system of tracking complaint calls and arrest records in the city of Santa Ana is being introduced with assistance from ICITAP, a U.S. government police training program. It promises to shed some light on these questions. Meanwhile, the press focus is on the rapid growth of two U.S. youth gangs, Eighteenth Street and Mara Salvatrucha. This has created a public perception that youth are the principal perpetrators of the violent crime wave. This may be erroneous and also ignores an important question: what draws young people into gangs?

Miguel Cruz, who teaches at the Jesuit- run Central American University, seems an unlikely person to have that answer.

It would be hard to imagine this mild, intellectual, who conducts political campaign polls and public opinion surveys, approaching gang members, much less training them. But that is what Professor Cruz has done. “We trained gang members to be investigators for our public opinion survey of the gangs” he explains, “because we realized that if a bunch of university professors and students could even get gang members to talk to us, the responses would have been much different.”

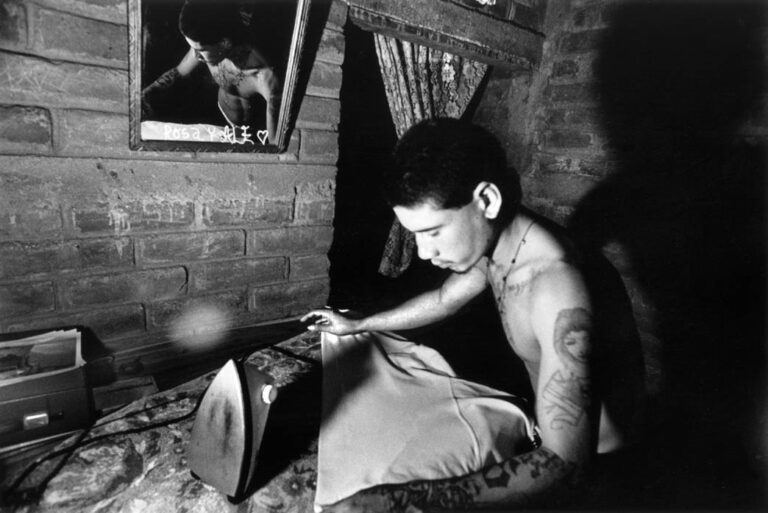

Edgar Bolaños, known as Shy Boy trudges to the edge of a soccer field with his friend Scrappy a few steps behind. They are searching for the original Shy Boy. Even the walls of this village in rural Sonsonate are marked with gang symbols. But Shy Boy passes the graffiti disinterestedly. He’s not looking for a local homeboy. He changes direction several times, finally spotting what he is after — his brother Jose’s grave.

Cruz’s survey of more than 1,000 gang members from Mara Salvatrucha and Eighteenth Street gangs in San Salvador offers evidence that most are seeking respect and friendship as well as a new family identity. More than 80% of the youth interviewed said that violence was a negative aspect of gang life that they wished would end, although the majority are fatalistic about that possibility.

Edgar tells the same story I have heard from his mother, Ana, and his brother, Hugo. He is haunted by a three-year-old’s memory of soldiers torturing and killing his uncles and other villagers in a soccer field a few miles from the one near his brother’s tomb. He remembers the bravery of his grandmother withstanding soldiers’ punches for refusing to tell where his father, a guerrilla fighter, was hiding. His father was saved by a fierce loyalty and a refusal to talk. It’s a lesson learned well by the surviving Bolaños brothers.

The boys were raised by their peasant grandparents until Ana, who had fled fearing her guerrilla husband and the consequent army threats on her life, was able to send for her sons to join her in Los Angeles in 1989. But the boys clashed first with their new stepfather and then with Chicano gang members in school. It was not long before Hugo and Jose joined the Mara Salvatrucha gang. Edgar was only 13, when to his mother’s dismay, he followed in his big brother’s footsteps.

“My mom brought me back here to El Salvador, because Jose told her some Eighteenth Street gang members were going to kill me in Los Angeles,” Edgar says in a low voice. “The bullet meant for me got him instead.”

Although according to Edgar’s mother, her son Jose was killed because he was in love with a girl from the rival Eighteenth Street gang, Edgar reacted by taking his dead brother’s gang name, Shy Boy. Shortly after Jose’s burial, Edgar tattooed a tombstone with the name Shy Boy on his back.

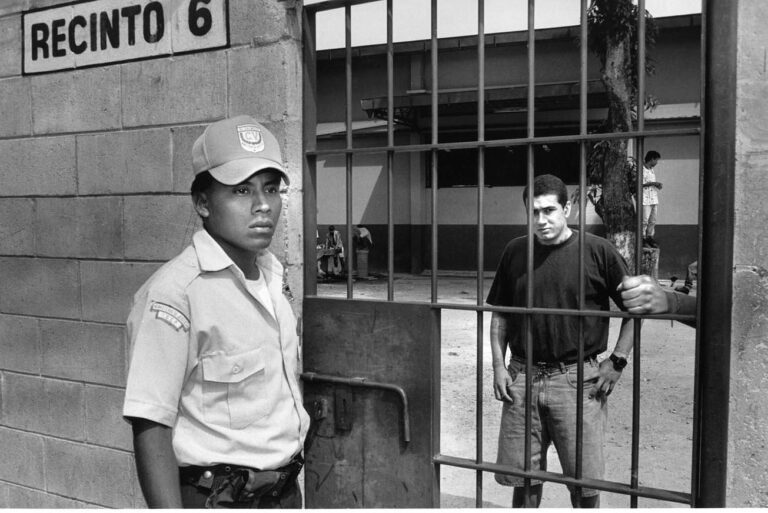

Apanteos, the model prison recently opened in Santa Ana, is the pride of the Salvadoran Ministry of Justice. The philosophy focuses on education, not punishment. But Apanteos is an exception in the penitentiary system, in part because the inmates here have not yet been sentenced. At least another nine traditional prisons are needed, Justice officials say, in order keep up with new convictions and to relieve over-crowding that has led to violent prison uprisings in which inmates have been hacked to death by other knife-wielding prisoners.

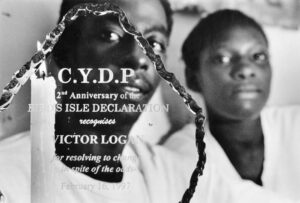

Hugo Bolaños was moved from the infamously brutal Mariona prison to Apanteos when it opened. “Tell Edgar I’m ok, it’s more like an American jail here,” Hugo says forcing a smile. But desperation is visible on Hugo’s face. He has already spent five months in detention waiting for his case to be heard. His lawyers believe he will be acquitted, but it could be another 6 months until the trial.

Hugo is charged with being an accomplice in a murder case because he refused to testify as a witness. Hugo says a drunken gunfight broke out between a cop and Hugo’s friend, who is an ex-cop. Hugo’s friend was wounded, but the cop was killed.

“The way I see it they both were at fault,” Hugo says shaking his head.

“But if I say I saw what happened, my friend would get life, because the guy who died was a cop. What would you do?” he asks rhetorically. “I know I should pick better friends. But I can’t be a snitch; the guy has kids.”

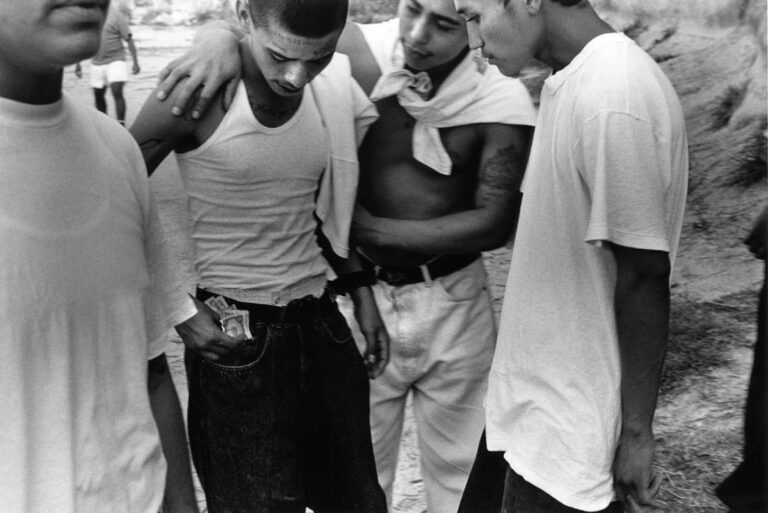

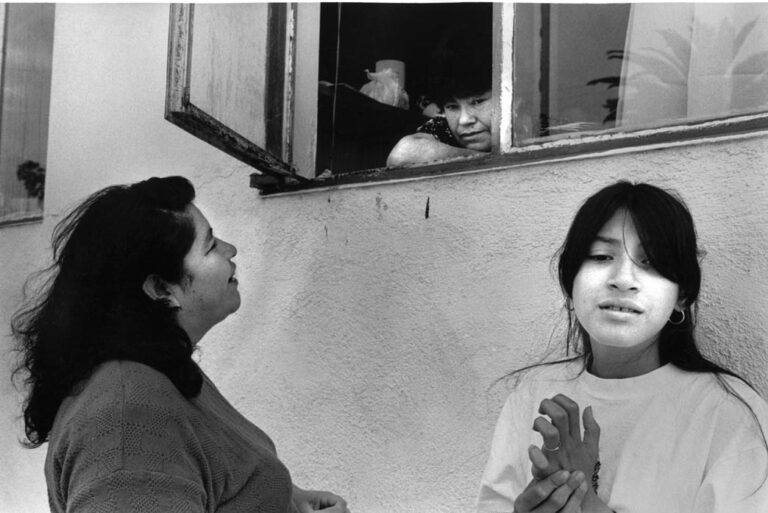

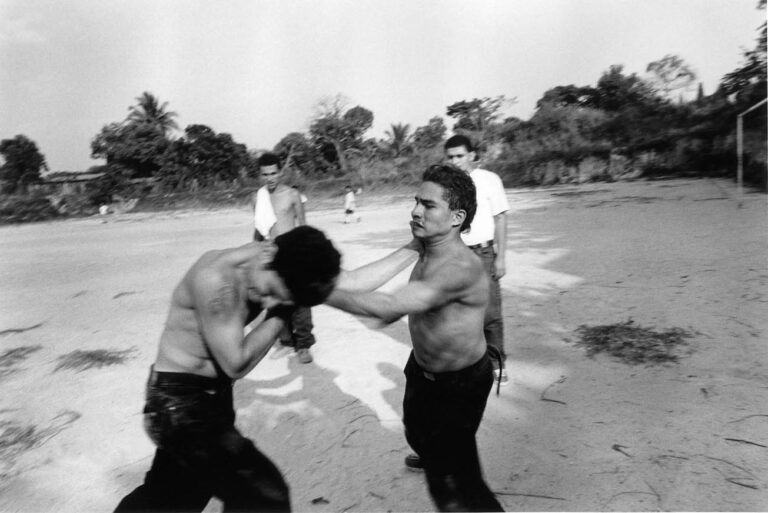

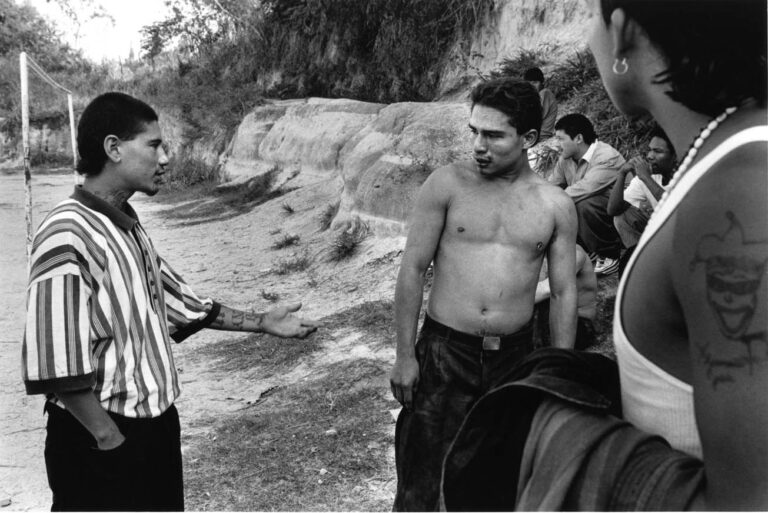

The gangs have their own informal court. At one “hearing,” a young woman in tight jeans and a midriff-blouse addresses the “court” glaring at the accused. “He had no right to touch me,” she shouts. “He put his hands all over me. I was waiting for the bus.” Wagging her fingers and waving her arms, she adds in threatening tones, “I am a married woman and my husband is very, very angry.” Standing beneath a shade tree, children in tow, her spouse nods his silent agreement.

Facing her, the young man accused of the misdeed begins moving forward, sweat pouring from his brow. Several youths step up to block his path to her, as his denies the charges.

The crowd listens as the adversaries face off, howling accusations and counter accusations. When someone interrupts to defend the accused, the gathering erupts in unruly shouting, as all seek to air their views or seize the opportunity to vent unrelated grievances.

Spider restores order, giving each homeboy from the Big Gangsta Locos a chance to speak. Spider motions the accused and his brother Spike to his side. The verdict is unspoken but understood.

Within seconds, dust clouds explode as the sentence is meted out. The crowd of homeboys and onlookers cheer and shout like spectators at a cock fight.

The face of the accused becomes caked with blood and dust before he slowly staggers away.

But it is not over. “That’s all you are going to do?” the woman demands of Spider, incredulously. From the back of the crowd, the humiliated youth winces in pain moaning, “I had no idea she was married to a homeboy.”

Shy Boy is among the gang elders who begin persuading both parties that justice has “been served” and the incident must now be forgotten. Gradually the woman calms down as her husband wordlessly indicates his acceptance. Spike embraces the punished homeboy, they do their gang handshake and everyone relaxes.

“The vato molested the homeboy’s wife.” Shy Boy explains, “If she’d been a woman from another neighborhood, maybe we’d laugh about it over a few beers,” he shrugs. “It’s not right, I know,” he says somewhat ruefully. “But that’s street justice L.A. style and that’s how we are here too.”

Such “street justice” can uphold a gang members rights within the group, but it can also be rough and brutal. Disloyalty or disrespect toward someone from the same gang is a serious infraction. Snitching to the cops or consorting with enemy gangs are the worst offenses and those accused often pay with their lives.

Luis Polanco owns the grocery shop at the top of the cul-de-sac where Shy Boy’s clique gathers. As Polanco looks around his working-class enclave, he says there is a feeling in the air that reminds him of the early war years when things began to fall apart. He knows of at least four different groups in his neighborhood, who are arming themselves to eradicate the youth gangs.

“They are waiting, but they are serious and one of the local police agrees with them.” Polanco says in hushed tones. He understands his neighbors’ resentment and frustration. “You ask yourself, ‘Why should I work sweating like a slave all day to sell Coca Colas, and have these vagabonds constantly begging for money to pay for their drugs and shiftless life?’” He shakes his head and continues, “This war here did terrible things to people. And what was it all in the end except poor people killing other poor people.”

Edgar Bolaños, has begun thinking about the future. He wonders if there is some way he can take off the tattoos, at least the ones on his face and arms. He wants to get a job so he can have kids. But there is another reason too. Shy Boy is beginning to realize he does not want to die. He is at a turning point, struggling more urgently with questions of long- term survival, as he thinks for the first time about who he is and what he wants

Edgar Bolaños is the new El Salvador, caught between a peasant past and modern dislocation, caught between the generation of romanticized rebel fighters and that of vilified young gangstas. His search for identity parallels El Salvador’s search for a shared definition of justice, respect and participation.

©1998 Donna DeCesare

Donna DeCesare, a New York photojournalist, is examining youth identity and gang violence in the Americas.

![At the Haitian National Penitentiary, Touchè Caman does outreach for Chans Altenativ. looking for deportees among the inmates. “I never thought I’d be going back into a prison after the last time,” he tells me laughing. “It’s a lot different on the other side [of the bars]. “Maybe Chans Altenativ can help a few of them when they get out.”](https://aliciapatterson.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/DeCesare_Haiti01-300x204.jpg)