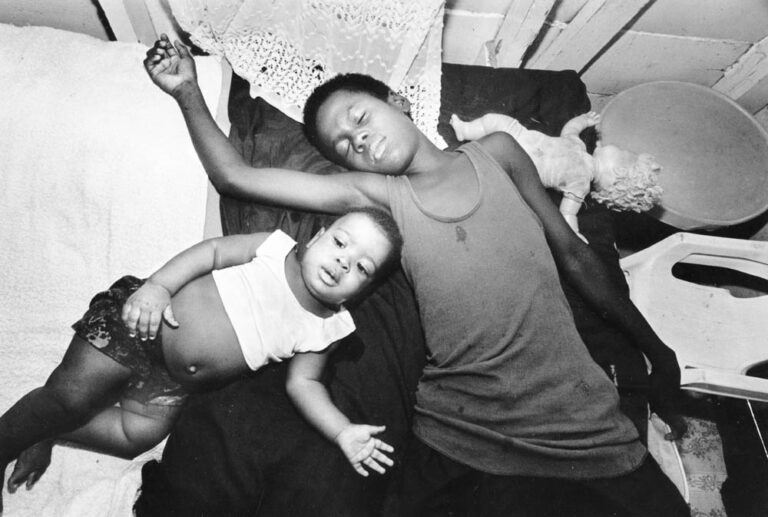

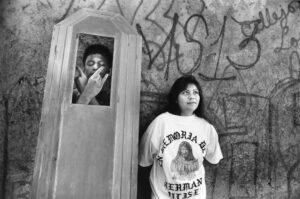

Belize City, Belize–”Stinga,” is a Conscious Youth success story. The former head of the Black Scorpion Posse, BSP, is one of the original gang leaders, who signed a historic truce halting gun battles on Belize City streets. Stinga surveys his muddy surroundings before venturing from the water-logged cubbyhole where he lives with his 17-year-old girlfriend Candace. He is one of the few peacemakers who is not dead, currently in prison or once again an active gang member. Stinga owes his survival not only to his precaution, but to participation in the Conscious Youth Development Program, a government effort to rehabilitate gang members.

Despite his success, Stinga’s environment is closer to early 60s Mississippi delta than the Belizean paradise islands and rain forests the eco-tourists admire. Mosquitoes breed in sewage-polluted canals and drainage ditches throughout the city’s sprawling slums. Toys, even crayons, hardly exist. UNICEF estimates that one in ten Belizean children never enter primary school. Of those who do, just over half finish sixth grade. For Belizeans Stinga’s age, the odds are worse. Less than a third of youths who are 14 to 21-years-old attend school. More than half of the dropouts are also unemployed. A handful of dilapidated open spaces or parks–some sporting signs forbidding games–and a huge cemetery, offer the only shady respite from a punishing sun and the stresses of poverty. With the truce fraying as it approaches its third anniversary, gunshots are once again breaking the humid night.

These days there are three TV’s in Stinga’s dank cubicle. He and Candace focus on staying out of trouble, spending the hours they’re not looking for work, surfing more than 50 pirated cable channels on the one TV that works. They are barely literate and as impressionable as people half their age. Marveling at the glittering detritus of American dreams and tawdry and violent icons of the American ghetto, they claim these icons as their own. “Check, just as many Belizeans live in South Central Los Angeles as in Belize City,” Stinga says, smiling.

Until the truce, Stinga lived side by side with death. The Black Scorpion Posse hid its guns among the cemetery’s tombs and themselves in open graves. They would unnerve Crip enemies by rising from the graveyard in the moonlight, wailing like banshees. From his childhood, Stinga remembers violent nighttime “games” or torturous pranks played at Listoway, the boy’s home where he was interned for nine months for smoking marijuana at age 14. He graduated from detention with plenty of anger, tough connections and a dangerous ethos: inspire fear or live in it. “It’s not the dead you have to fear, it’s the living.” Stinga remarks philosophically. By sixteen he was a leader of the BSP, at the top of a world of robbery, drug dealing, gun fights and wild parties.

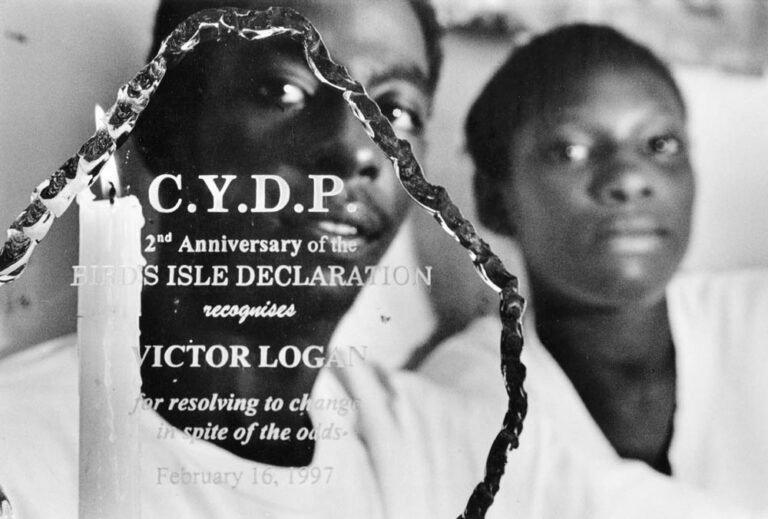

Now, Stinga goes by his real name, Victor Logan. Through Conscious Youth he speaks to school classes about the terror of life in a gang. Candace supervises troubled children at the Conscious Youth summer recreation program . A recent job, working alongside the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers building school classrooms for handicapped and special needs children, has added to Victor’s construction experience. “Things are a whole lot different for me since Conscious Youth,” he says proudly.

Stooping to avoid hitting his room’s five-foot ceiling, Victor roots around for the envelopes that hold his most prized possessions–certificates of achievement from Conscious Youth. “I got my fame from negativeness,” he confides. “Right now I’m trying to get my positiveness because if we can’t hold down the badness, the little ones will pick it up.”

He still loses his patience when his younger brothers flirt with trouble. But he has learned to walk away from conflicts with authorities and to articulate his views confidently. Recently, he spent a few nights locked up in the police station “piss house,” a cell so named for its lack of sanitary facilities. According to Victor, his mother and his neighbors, the officer who took him in was drunk and abusive, first toward Victor’s younger brother, and then toward Victor, pistol whipping him with a gun and ramming his head into the side of the police jeep while threatening to kill him. In the old days such abuse would have triggered a rage. This time, Victor calmly filed an official complaint.

Despite his new-found self-control, the odds against Victor are great. He has little education. He has no job. But he is not discouraged. “I have had work. I have my dream. If the truce lasts or doesn’t, I’m not going back. If the other sets (gangs) roll on my base they’ll have to kill me. I’m not in that anymore. I’ll try to build up my own house, and find work in construction or at the Pepsi factory near my plot of land.”

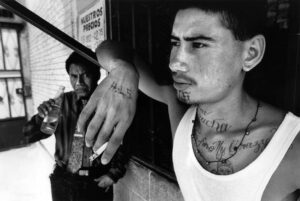

Democratic traditions, rooted in its experience as a British colony, distinguish Belize from the military dictatorships that ravaged its neighbors. But the British retreat in 1981 opened the way to a host of new invaders: spiraling corruption, Colombian cocaine dealers, and American pop culture. An influx of poor Hispanic and wealthy Chinese immigrants have fueled racial tensions, leaving Belizeans, especially black Belizeans, feeling a minority in their own country.

As gang violence and vigilantism swept Central America and the Caribbean, Belize adopted a bold plan to contain the outbreak. Belize traded the region’s traditional mass detention strategy for an olive branch. In 1995, it embarked on a visionary journey, combining a gang truce with criminal justice reform and government social programs to educate and motivate disadvantaged youths. The Conscious Youth Development Program and the Youth Enhancement Academy are cornerstones of this progressive effort.

Inspector Edward Broaster helped to broker the gang truce. Broaster’s role in ending the mayhem between Crips and Bloods, which claimed the lives of 89 black youths in a city of only 50,000, placed him at the helm of Conscious Youth. He is understandably proud of the record number of conflicts he’s resolved peaceably and the many lives saved by the recovery of more than 50 guns during his watch. Conscious Youth offers some impressive services, including job and training referrals, parent support, conflict resolution, and a summer recreation program.

Recently, the Caribbean Development Bank evaluated Conscious Youth. The report praised program goals, but found several weaknesses such as staff feuding, project design flaws, and an ad hoc management style. Especially perplexing is the lack of a trained social worker or psychologist in a program whose stated goals are rehabilitation and human development. “We did it the wrong way,” says Nuri Muhammad, a former Conscious Youth staffer. “What we needed was a human development program with a police component, instead of a police program with a human development component.”

Broaster is a cop who cares. But his top priority is not empowering kids, it’s stopping crime by recovering guns. The smorgasbord of social services is simply the carrot he uses to capture them. But there is no consistent record keeping, documentation, or assessments for Conscious Youth activities. The result is far less than the original vision of developing gang leaders into community leaders who could help other marginalized young people. There are many reasons that vision remains unrealized, but chief among them is Conscious Youth’s reputation on the street. Says one unimpressed gang member, “It’s a snitch program and you don’t even get a job.”

Despite these short-comings, Conscious Youth has helped turn Evalee Cadle’s life around. She was unemployed, pregnant with her sixth child and battling an abusive boyfriend when she came to the program. “Those were times I thought a lot about suicide,” she confides. After counseling, night classes in cosmetology and enrollment in a micro-enterprise loan program, Evalee was able to open her own beauty salon. She has become an inspiration to others, and is currently the President of the Conscious Youth Council.

The Youth Enhancement Academy, a boot camp for first offenders, is Belize’s latest attempt to rehabilitate and motivate gang members. Nuri Muhammad became co-director here after leaving his post as outreach coordinator for Conscious Youth. He and Inspector Broaster are supposed to be on the same side, but you’d never know it from listening to Muhammad’s lecture. Today he is talking about faith and change. Some of his 25 pupils still sound as if they are speaking by rote, like the military style drills they are put through each day. But others are beginning to trust enough to express their personal feelings. When class ends after 45 minutes, they snap to attention and file out to the parade grounds, once again resuming their drills.

Muhammad explains that the intention is to keep them occupied until other rehabilitation programs like carpentry workshops and literacy classes can be organized. “This program is an idea in progress. The point of all this is discipline. We know they aren’t going to march down the street when they get out. What we want is to give a sense of responsible manhood. “

There is an ironic twist to all this. The two men charged with teaching Belizean youth about peaceful co-existence can barely contain their mutual animosity. Broaster and Muhammad are like oil and water, and it’s easy to see why. Broaster is a macho jock whose training beyond Belizean high school has been police training. He is a mercurial hipster, shrewd rather than thoughtful. Muhammad is a Muslim intellectual with experience working in Harlem and in the the prisons of Los Angeles. He is an inspired orator with an intuitive street style and a compassionate manner. After their initial cooperation in the truce and during the first phase of Conscious Youth, their different styles and visions began causing friction. With their intuitive sense of real politic, the kids guard what they say to Broaster’s face. They know his power. But they reserve their respect for Muhammad. “Actions speak louder than words. Mr. B. yells, or just don’t show up then laughs it off. He don’t care for youths anymore. Mr. Nuri always listened.”

Belize deserves to be applauded for trying the most progressive reform program in the region. But it is disappointing to see it fall so short of realizing its potential, largely because of the personal rivalry that seems endemic in Belizean culture. “We Belizeans have a limelight mentality,” says Muhammad. “Gang members talk about ‘biggin up.’ It’s our political culture. Egos bruise easily.” And Muhammad adds that the colonial legacy of a stern Calvinist “spare the rod and spoil the child” attitude left Belize with a pervasive harshness that taints institutions as well as homes. This under- current of cruelty nourishes the breeding ground of violent crime.

Inspector Broaster has risen in the Belizean Police force faster than any other cop and he doesn’t hide his ambition. He wants to be Police Commissioner someday. He believes he can make a difference. As Broaster tells it, his conversion from a head-busting “Dirty Harry” cop to peacemaker began when he was approached by some businessmen in 1994. “They told me I could have anything if I’d smoke a few of the gang leaders,” he says, grinning. Instead, Broaster took a proposal for a gang truce to his Commissioner.

Broaster‘s conversion may not be as radical as he likes to think. In many ways he is still a creature of the brutal system he is trying to reform. Broaster believes he is making peace, but he is not above coercing confessions or testimonials with physical or psychological arm-twisting. Conscious Youth uses a carrot and stick approach, lecturing “good” kids by day, rousting “bad” kids by night. “I do everything to keep them from going to prison,” Broaster says, explaining the good cop, bad cop tactics. “When they do something which lands them in prison, they are not for me anymore.”

With the Conscious Youth Development Program and the Youth Enhancement Academy, Belize is challenging trends not just in Central America, but around the world. At a time when other nations, including the U.S., are passing laws permitting children to be tried as adults and dealing harshly with young criminals, Belize stands apart. Its vision is unquestionably bold and progressive, but far from a quick fix. No initiative focusing on a single problem–faced an impoverished nation emerging from colonialism and struggling with drug corruption–could be.

Despite the magnitude of the challenges, Muhammad is excited. “Belize is like clay. In America I could only make an impact on an individual level, but never on the system. Here it’s still possible to make an impact on the system itself.”

©1999 Donna DeCesare

Donna DeCesare is a photojournalist in New York who is examining youth identity and gang violence in the Americas.

![At the Haitian National Penitentiary, Touchè Caman does outreach for Chans Altenativ. looking for deportees among the inmates. “I never thought I’d be going back into a prison after the last time,” he tells me laughing. “It’s a lot different on the other side [of the bars]. “Maybe Chans Altenativ can help a few of them when they get out.”](https://aliciapatterson.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/DeCesare_Haiti01-300x204.jpg)