(abortion campaign in West Germany)

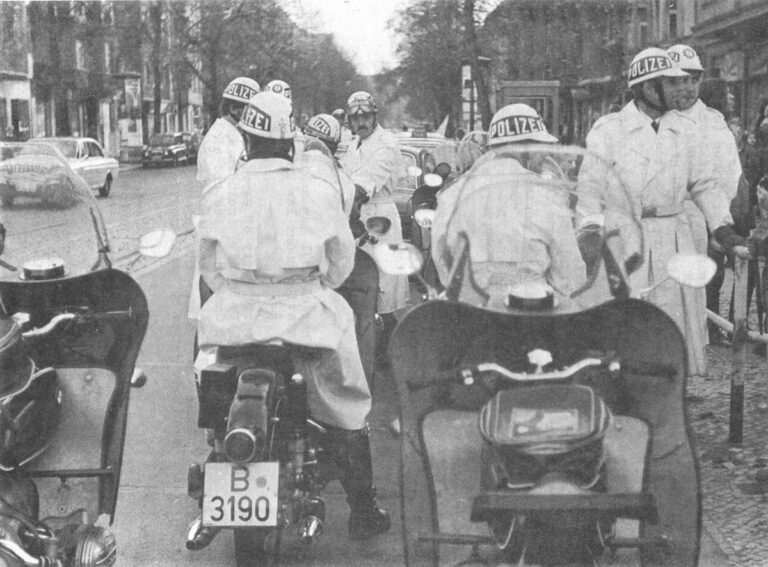

West Berlin, January, 1971

Photos used in this article courtesy of Frank-Michael Urban, West Berlin.

“They say this law is the last wall of moral.…If this is the last wall of moral then that wall is not far away…Moral has nothing to do with this because it always comes out the way the powers that rule say it should.”

— (Frau Hodann at rally for “legal abortions, work and bread,” Stuttgart, 1931)

At six a.m. on. June 22, policemen in groups of 30 raided the apartments of Edda Albrecht-Wagner, a student, and Ute Geissler, a bookkeeper, on deserted Munich streets. Ignoring questions from the sleepy women, the police in both places methodically collected every scrap of paper within reach. Two hours later they reported to the Bavarian prosecutor with 3,000 signatures calling for legalized abortion, several lists of contact addresses, mimeographed pamphlets, minutes of meetings.

The materials were returned later, presumably parts were photocopied, and the prosecutor admitted he didn’t find what he was looking for – the signatures of women who confessed to Stern magazine on June 3 they had had illegal abortions.

In a rare departure from its covers of different sized, shaped and colored nudes, West Germany’s most popular illustrated weekly filled its front-page with the heads of 25 women under a banner saying, “We had abortions!”

On the inside pages in small print, Stern printed the names of 374 women who dared law enforcement officials to arrest them for undergoing illegal abortions. The idea was not original. Modeled after French women Simone do Beauvoir, Francoise Sagan, Jeanne Moreau and others who “confessed” to having had abortions in the April 5 issue of Le Nouvel Observateur, the German sensation did not lack for celebrities – Romy Schneider, Veruschka von Lehndorff, Senta Berger.

But whatever one may attribute to the motives of Stern, which was persuaded to follow up its initial article with more self-accusations, the appearance of the testimonies marked a turning point in the thus-far quiet debate on abortion reform.

Women’s groups came into existence almost overnight when 2345 women made public self-accusations, 973 men admitted to being accomplices and within a few months 100,000 signatures were collected calling for the repeal of Paragraph 218 – West Germany’s 1871 statute prohibiting abortions.

The open violation of the law, and the subsequent publicity resulting from it did precisely what critics of the campaign most feared – “pushed the issue onto the streets” – and thereby inserted another set of opinions into the heretofore closed dialogue conducted between the government and the churches.

Or as Herbert Kremp, senior editor of the Hamburger Die Welt wrote on June 15: “…the thousands of signatures gathered against Paragraph 218 were begun…by some suffragettish unmade-up stars and their advertising journalists…to put pressure on the Justice, the Executive and the Legislature…” Its sister newspaper, the tabloid Bild (largest in the country), countered by running atrocity stories of innocent German girls driven to blood and pain in London’s legal abortion clinics under banner-headlines saying, “Never Again to England!”

But the above newspapers are owned by Axel Springer and noted for their reactionary comments. However, it was the liberal Frankfurter Rundschau which first advocated taking the “discussion off the streets” while the equally liberal Sueddeutsche Zeitung of Munich warned against “exhibitionism.”

Few government officials accepted the challenge as quickly as the newspapers and Alfons Goppel, premier of the State of Bavaria, who ordered the raid on the two members of the Munich socialist women’s lib group (Socialistischen Arbeitsgrupper zur Befreiung der Frau). Although no arrests followed, the raid served to underline Catholic Bavaria’s stand on abortions – or, as the women contend, was designed “for purposes of sheer political intimidation.”

In many other German cities, the proper noises were made about investigations and some complaints were filed (i.e. against Romy Schneider in Hamburg). Other investigations are still continuing. But in general prosecutors avoided giving further aid to the campaign by spotlighting the issue in their offices. (In West Berlin, the prosecutor declined to act even after the Socialist Women’s League and the Humanistic Union handed him a list of violators.)

“We have two choices…either to repeal the law because of the great misunderstandings between the statute, its perpetrators and its violators…or to prosecute vigorously…I of course am for the second solution…”

— Bavarian prosecutor, Munich, 1922.

“The Stern story has made a mockery of the law…people openly boasted of violating it. This action requires the State to use its power…If the police acted improperly that of course is another matter.”

— Bavarian State premier, Munich, 1971

The reluctance of the law to take action points up the contempt with which Paragraph 218 is regarded in this country, where the legal system is often treated as abstract truth to be obeyed with fervor. Aside from untold numbers of women who travel abroad for abortions, the Bonn government itself estimates the number of German-based operations at over 500,000 a year among about 22 million women of child-bearing age. The registered prosecutions have dwindled to an all-time low of about 1,000. Punishment in practice is confined to fines rather than jail sentences.

In fairness to the Social Democratic-dominated government, the issue of reforming the 1871 law has been. part of the party’s program since the Weimar Republic of the 1920s. In his package of legal reforms when the Social Democratic Party (SPD) came to power in 1969, Justice Minister Gerhard Jahn immediately announced proposals to overhaul the country’s divorce laws.

Not only did the Minister propose a simple divorce “after a marriage had broken down” but suggested that women who did not have small children be encouraged to earn their own living rather than have an absolute right to alimony.

The proposals were in the main quite progressive, particularly as a legal superstructure to a society that may emerge in the year 2,000. Many older women, however, with reason expressed fears they would be left to their own resources in a job market which offered them little hope of a decent position. Without attempting to analyze the divorce controversy in detail here, the conservatives convinced Dr. Jahn to water down many proposals, mainly by using the “kinder, kirche, kueche” argument.

In opposition, there was little evident pressure from women or women’s groups who might have approved parts of Dr Jahn’s proposal – mainly because such organizations were practically non-existent.

As a result Dr. Jahn, in tackling the abortion law, was prepared only for the storm on the right – from those who preferred to keep the present law which forbids all abortions. Legal precedent since 1925 has permitted a pregnancy termination in cases where the mother’s life is in danger.

To this exception from the 1871 law, the Minister wants to add: cases where the woman is raped, where the child may be born deformed and in situations of extreme social need. The “social need” issue is the one giving the Minister trouble. He has stated however that social need will not apply to single women, who fear pregnancy because of interruption of career or studies.

The conflict over “social issues” in the Bonn government cabinet has forced the Justice Ministry to date to present 13 draft proposals, all of which have been rejected. thereby delaying parliamentary action.

“There has never been a rich woman before the dock on grounds of violating Paragraph 218.”

— SPD Justice Minister Gustav Radbruch calling for legalized abortion during first three months of pregnancy, Berlin, 1921.

“…I don’t call it progressive but conservative, if one is unwilling to re-evaluate the theses (SPD program on legalized abortions) of the 20’s in relation to the changed conditions of the 1970’s.

— SPD Justice Minister Gerhard Jahn, interview, Hamburg, 1971.

Unaware of Dr. Jahn’s cautious approach to abortion reform, Catholic groups were among the first to obtain a public response on the issue from the Minister. Past resolutions from the SPD Women’s Conference, the Young Social Democrats and several trade unions indicated the party was considering a substantial change in the abortion law – complete repeal or abortion-on-demand during the first three months of pregnancy.

Towards the end of 1970, the Catholic-oriented tabloid Bildpost began to campaign against a change in Paragraph 218. In the town of Passau near the Austrian border, 12,000 signatures were collected quickly under a slogan of “Minister Jahn wants to legalize murder.” Letters were exchanged and Justice Ministry officials early in 1971 answered that there must have been a “misunderstanding” because the government had no intention of repealing the law or introducing a “three-month plan.”

In tracing the beginnings of the abortion debate, free-lance journalist Alice Schwarzer was convinced that “large parts of the population were unaware of this exchange…and believed a repeal of Paragraph 218 would be forthcoming.”

Shortly afterwards the Christian Democratic Party, whose close ties with the Catholic Church prevented it from raising the issue while it was in office, began to question Minister Jahn on his intentions. In answer to parliamentary queries, the Minister said the government had not yet formulated a proposal. However, on the heels of the parliamentary questions came firm statements from church groups. The Catholic Church and its lay organizations aligned legal abortions with legalized murder. The official Protestant groups had more difficulty with the issue, and believed a limited easing of the current law would be in order.

“A…liberalization of conditions for obtaining abortions is incompatible with the Christian conception…of the unborn life.”

— Julius Cardinal Doepfner, head of Catholic Bishops Conference, Munich

As details of the Jahn plan became clearer in the summer and fall of 1971, the tiny Free Democratic Party (FDP), which had been toying with a liberal reform of Paragraph 218, saw its chance. The FDP, despite its small numbers, gives the Social Democrats their parliamentary majority of six over the opposition Christian Democratic Union (CDU). The Social and Free Democrats form a coalition government.

The Free Democrats stand for traditional liberalism, which varies depending on whether the party is in partnership with the Social Democrats or the Christian Democrats. It was mainly formed to give liberal-thinking industrialists an alternative to a Catholic-oriented political party. To attract segments of the middle class, its program usually contained an emphasis on civil liberties and approval of the consumption and fun ethos. However, the FDP has been dwindling in support as the Social Democrats dropped almost all concepts of classical socialism and the Christian Democrats showed industrialists were safer in a large conservative organization.

By June, the FDP declared itself for abortion-on-demand during the first three months of pregnancy. The party’s draft bill includes an advisory service for the pregnant woman, but leaves the final decision in her hands. After the first three months of pregnancy, abortion is permitted only if the life of the mother is in danger or evidence of deformity is shown in the fetus.

After the FDP plan was announced a number of groups supported it – including the Young Social Democrats, several SPD women’s caucuses, the Trade Union Federation, various women trade union groups, the Women Jurists Association, branches of church (protestant) groups, and even the November party conference of the Social Democratic Party.

“One is greatly suspicious that the Church is not arguing over the lives of human beings…but the punishment of the mother. If she ‘sins’ she must suffer, if she decides not to bring an unwanted child into a hostile world, then she should at least be punished for relieving her conflict.”

— Dorothee Soelle, professor of theology, radio broadcast, Stuttgart June, 1971.

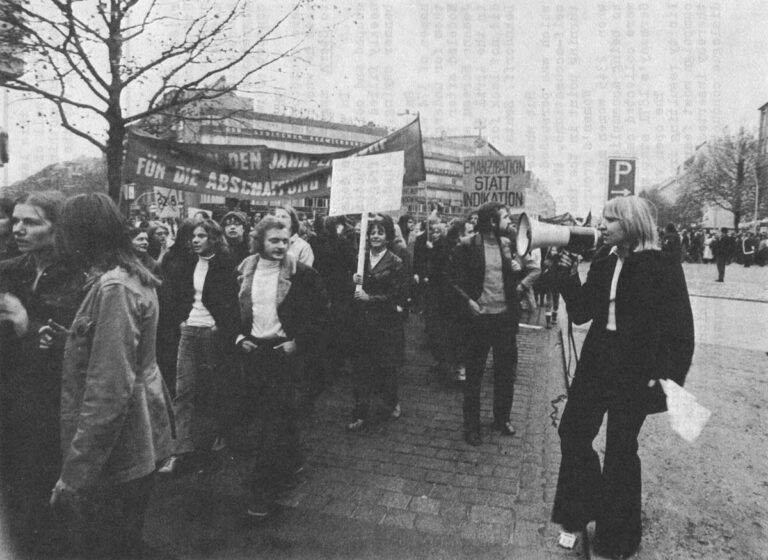

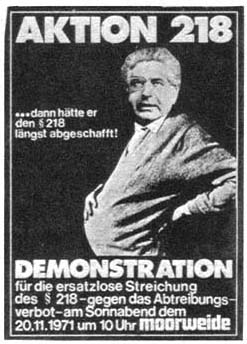

But few of the major demonstrations or petition-collecting campaigns outside of the political parties were a direct result of FDP organizing. The Free Democrats too declined from taking the issue “into the streets”, although individuals from the party as well as from the Social Democrats supported some of the public campaigns

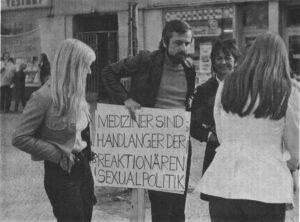

The core of the anti-abortion law campaign came from the independent women’s groups organized in a loose federation called “Action 218.” Most of these women (and some men) were in favor of a complete abolition of the law on grounds that a time limit for abortions can only be determined by medical reasons. (For example, a pregnancy termination at six months or later can result in a premature birth and not an abortion so therefore is not relevant to the argument).

Action 218 also spends much time on the “class nature” of the current law which it contends was not alleviated in the Jahn proposals. Articulate or wealthy women will be able to tackle the complicated procedure for obtaining an abortion envisioned in the government plan. They can also continue to go abroad to England or to Holland for a legal abortion.

“Underprivileged women” reads one leaflet “are kept in a dependent state to further exploit them, deny them easy access to contraceptive information and then defame their illegitimate child.”

Included in the program is wide-spread dissemination of contraceptive materials, abortions and contraceptives covered by health insurance, more kindergartens, aid to large families, a year’s paid holiday without loss of job to mothers or fathers who care for new-born infants.

“Today we turn to you because Minister Jahn has a proposal to reform Paragraph 218 which is against your interests. He offers no real change for the catastrophic situation of women. who are victims of an unwanted pregnancy….”

— Speaker, Action 218, West Berlin, November,1971.

“If he (Jahn) believes he can comfort us with his liberal reforms, he’s again wandered into the wrong corner.”

— Christian Democratic Party legislator, Bonn, November, 1971

Several of the women’s groups involved in Action 218 (Frankfurt, Munich, Duesseldorf, West Berlin) were in existence before the abortion campaign. The Stern testimonies were in the main organized by the Munich and West Berlin groups brought in contact with various individuals by journalist Alice Schwarzer. Many other groups either organized last spring or summer or were skeleton associations which received a new surge of members after the Stern campaign.

After an initial surge of activities, about 16 groups met (four times to date) in a loose national coordinating conference under the name of Action 218 to exchange information, structure the campaign and tackle the idea of a general women’s movement for West Germany and West Berlin.

“Details of such a venture and a political analysis of the women’s groups have been deliberately left for a subsequent newsletter on West Germany.”

If a coherent women’s emancipation movement develops, it will be due to the initiative of these groups with their strongest chapters in West Berlin, Frankfurt, Munich and Hamburg.

With some overlapping, there are easily another 16 groups concentrating efforts or legalizing abortion – the Humanistic Union, the Communist Party of (West) Germany, various trade union branches and professional committees as well as chapters and individuals from the government coalition parties. Cooperation with the Action 218 groups is haphazard and varies from city to city.

Action 218 however, distinguishes itself primarily in two areas. It is for total repeal of the abortion law and is the drive behind most of the public demonstrations and the subsequent publicity. (It also has a larger share of unprofessional politicians than any of the other active groups).

How all this activity strikes the “silent majority” of West Germany at the moment can only be ascertained by the professional poll-takers.

With each successive month of the campaign, the various polls undertaken by the Allensbach and Infratest institutes show a growing sentiment for both the FDP’s three-month plan and complete repeal. (To my knowledge the two proposals have not been placed side by side in a reasonable form to date).

A poll last March resulted in 48 percent in favor of repealing the current law, 35 percent against, the remainder undecided. In July a poll on the three-month plan drew 59 percent in favor, 25 percent against, and in November both the repeal and the three-month proposal drew over 70 percent support.

Polls were also taken in the medical profession, although precise details on some of them are difficult to obtain. General practitioners were reported to have been in favor of the three-month plan and gynecologists in general for the Jahn proposals. Although the latter survey is the one used most often by the Government in public statements, both surveys were criticized by numerous sociologists as providing few available alternatives and submitting questions of a highly suggestive nature.

In all of the polls however the Jahn proposal as a complete package was found impossible to present accurately. As the proposals to the cabinet kept changing and the “social needs” redefined several times, pollsters found it necessary to draw up their own long list of “social needs”. All of them met with overwhelming approval. (Translated into practical terms, almost every woman under the pressure of pregnancy could qualify for one of the “social conditions” providing an intelligent and sympathetic physician could word the application properly.)

The question that must be asked then is why the Justice Ministry is backing an extremely complicated program, which if passed, satisfies no one and is both awkward to administrate and easy to violate?

On a practical level, the Ministry after incorrectly assessing the response to its proposals, was riding out its own momentum. Once introduced to the press and worked out by three Departments (Labor and Health as well as Justice), it was difficult to reverse the procedure to a complete about-face.

Another consideration, also on the level of the practical, are the well-founded concerns about the Government’s six-vote majority in the legislature. The “realpolitik” consideration is in fact taking precedence in public speeches to the moral and legal arguments.

For example, when the discussion first opened, the Justice Minister was clear in stating he was morally opposed to abortion-on-demand in any form, as the unborn life would not be protected and this conflicted with the constitution.

By the time Dr. Jahn faced his own party’s convention in Bonn in November, the morality arguments were watered down and all references to constitutionality were dropped. The Minister, as well as Chancellor Willy Brandt and Parliamentary leader Herbert Wehner, spoke of the proposals largely in terms of what would or would not pass parliament.

“All viewpoints on this issue are legitimate ….But…it has no purpose for this party to support (the three-month plan). This…most likely will not carry a majority in Parliament….”

— Chancellor Willy Brandt to SPD Convention, Bonn, November, 1971.

Unconvinced, the delegates overwhelmingly endorsed the three-month. plan, after several female delegates (from West Berlin and Frankfurt) fought convention leaders to have the issue placed on the agenda.

No speaker questioned why the three-month plan would not pass parliament. When asked by newsmen, the blame was laid on the Christian Democratic opposition. However, this is not completely justified.

Several CDU legislators have said they would vote for a three-month plan or at least abstain from the voting procedure. The Free Democrats obviously favor their own proposal. Therefore it can be assumed the three-month plan will not or may not pass parliament, partly because of opposition within the ranks of the Social Democratic Party legislators.

No doubt there are SPD parliamentarians with deep religious convictions as well as strong moral reservations, but judging from a questionnaire distributed in parliament, most are awaiting the government proposal and have not decided yet what their moral position is.

Of the vocal ones, about 12 have formed a group to build a lobby for the three-month plan and an equal number were on committees which helped the Justice Ministry construct its proposal.

In the case of the Social Democrats, as compared to the Christian Democrats, tradition stemming from ideology plays a contradictory role on this issue. As noted earlier, the SPD during the Weimar Republic of the 1920’s, along with the Communist Party, not only promulgated a three-month plan, but brought it to the floor of the Reichstag in 1925, where it was defeated by centrist and right-wing parties.

At various times during the Weimar Republic, abortion reform had great appeal to the unemployed and organized workers. Women’s groups, as well as left-wing parties, argued that women and children were forced to labor under unspeakable conditions, that birth was reduced to supplying factories with manpower and the State with soldiers.

Today, the rationalization -programs of industry do not call for a large reserve army of unemployed, who if kept around in too many numbers will greatly disturb the social fabric of society. Industrial expansion in the long run is not predicated on an equal rise in the population. If, at various times more labor is needed, there is still a reserve army of women, who at present are still underemployed. (West Germany also draws on foreign workers for extra labor who can be withdrawn at will).

On the other hand women in West Germany, as in most highly industrialized nations, are a permanent part of the work force (even if in inferior positions to men) and could not be withdrawn without serious repercussions. Their numbers in the labor market and the concomitant of education has also resulted in a demand for more personal choice, particularly in areas of family planning.

Coupled with this development is a stress on the well-being of the nuclear family – the necessity to buy consumer goods or the desire to own things. This type of well-being can be hindered by overly-large families, which again would also raise the numbers in the work force. For both positive and negative reasons, the falling of the birth rate in the 1960s, whether through contraceptives, abortions or abstinence, is treated as a necessary fact of life rather than a blow to society.

Reflected in this context, the Government in raising the issue of abortion reform in the first place, reveals a recognition of the trend toward smaller families but not the necessity of the State relinquishing control on how the individual should bring this about.

A liberalized abortion law, however, while a basic step toward emancipating women, does not by itself alter the role of woman in the family or the structure of the nuclear family as a unit of consumption and component of the State. It can and has been argued that some family planning is needed to make a woman or man more mobile and adaptable to certain occupations in, an industrialized nation. This reasoning, coupled with a desire to appeal to the educated woman at this stage, accounts in part for the current abortion strategy of the Free Democrats.

In general, the present situation appears to show an increase of activity on the part of the Government to convince the public, including its conservative sections, on the need for some kind of family planning.

If the polls are any guide, a majority of the public at the moment is not only convinced of this need, but would agree to more radical ways of solving it than the Government is offering. Unconvinced however are parliamentarians in the legislature’s most left-wing party.

In the framework of this issue, the parliamentarians clearly are influenced by lobbies and pressure groups – the segment of the public which has proven itself to be most politically potent. And in this area the liberal and radical abortion reformers have produced a weaker lobby than the religious leaders.

Commenting to Stern in January, SPD member of parliament, Lenelotte von Bothmer, said she was getting the feeling that to some elements of the party, “…the small man and woman are always viewed as the dumb ones.”

Although admirable, the activities of Action 218 members have been fairly uncoordinated and at the moment present no serious political threat. Aside from the usual difficulties grass roots movements have in all countries, political organizing skills of women are particularly unpracticed here.

In comparison to Britain and the United States, West Germany lags behind in this area at least until the 1968 student movements. The years of Nazi dictatorship and post-war economic reconstruction, with its determined approach to affluence, still too often results in beliefs that politics should be left to the politicians.

Although this is changing, skills of groups organizing on a limited-issue basis within the realm of the obtainable and outside an institutional or political party structure are undeveloped. Some of the American practices (on housing, schools, abortion) such as pressuring a legislator by organizing sympathizers in areas he depends on for his votes is in general an untried approach here. At issue is not so much the success or failure of citizens attempts as the political skills developed through them.

This does not mean that American or British parliamentarians are more or less responsive to public needs than their West German counterparts, but that the public in the former countries in the post-war years is more used to doing battle with the politicians. And in certain situations this can make the difference between success and failure.

The abortion campaign still has months to go; its strength can be measured by whether a “compromise” in the end will be the Jahn proposal or the FDP-three – month plan. (Acceptance of the status quo is unlikely as despite the influence of religious bodies here. The present West German government is less dependent on them for support than, for example, the French or Italian governments).

But because times and conditions are right or ripe for a charge does not mean it automatically occurs through evolution, rather than. struggle.

Glossary.

Action 218 – Campaign to repeal 1871 law making abortions illegal. In statute books law known as Paragraphs 218 to 220.

SPD – Social Democratic Party of Germany, headed by Chancellor Willy Brandt, includes Justice Minister Gerhard Jahn. Came to office end of 1969 as senior partner in coalition with Free Democrats; two parties have a six-vote majority in the Bundestag, the lower house of parliament.

FDP – Free Democratic Party of Germany headed by Foreign Minister Walter Scheel, junior partners in Bonn government, smallest party in the legislature, holds balance of power.

CDU/CSU – Christian Democratic Union, Christian Social Union. Conservative opposition party linked to Catholic Church, although not all members Catholic. Union parties governed post-war West Germany until 1969 election. CDU headed by Rainer Barzel; CSU, its Bavarian sister party, by Franz-Josef Strauss.

Received in New York on February 10, 1972

©1972 Evelyn Leopold

Evelyn Leopold, a former news agency correspondent, is an Alicia Patterson. Fund award winner. This article may be published with credit to Evelyn Leopold and the Alicia Patterson Fund.