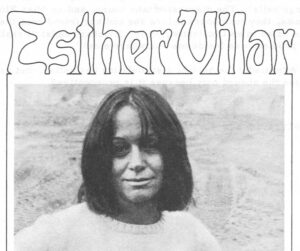

Esther Vilar

West Berlin

April, 1972

Esther Vilar was born in Buenos Aires in 1935 as Esther Margarata Katzer, the daughter of German immigrant parents. She studied medicine and spent several years working and traveling through the United States, Africa and Europe. After arriving in West Germany, Vilar enrolled as a sociology student and worked as an intern in a Munich hospital. She married a German writer, Klaus Wagn, whom she has now divorced. The couple has an eight-year old son. However Vilar and Wagn are still partners in a small publishing company, Caann, which in the past has produced their own works. Vilar has written several essays, a play, “The Summer after the Death of Picasso,” and a novel, “Man and Dolls.” She attributes her inspiration for “Der Dressierte Mann” to her angry reaction to the American Women’s Liberation Movement.

Once upon a time (about nine months ago) women’s lib people in West Germany thought of Esther Vilar as a bad joke who would go away. But she did not. Her short crisp book, “Der Dressierte Mann” (The Tamed Man Translations used in article by E. L.) stayed on the best seller list for months and months and is still there. A mixture of truth and fiction, humor and anger. Vilar’s book was serialized in newspapers, dramatized on television and destined for publication in several languages (including English).

In short Vilar turns all women’s lib theories (feminist as well as socialist) inside out. Men do not oppress women. Women oppress men. The social system does not discriminate against women, because they control it. Woman trains man to be her slave, to work for her. She tames man to work because she finds it more comfortable to be idle. Man who she has taught from birth submits to this slavery because he knows no alternative.

Is she serious? Vilar has been asked that several times and has answered that she “is describing serious situations with humor.” One must accept then that she believes in what she is writing.

More baffling however is her popularity, which indicates she is not the only one who takes herself seriously. Several explanations have come from her critics: “A super well-financed public relations campaign” (Der Spiegel magazine); “Prejudice and ignorance served on an attractive platter sell well” (A women’s lib leader in Berlin); “Germans are conservative in these matters and have been known for believing worse things” (An American journalist).

The above observations are not entirely invalid but neither are they far-reaching enough. Too many people read Vilar and many mistake her theories as a progressive and provocative step toward equal rights or emancipation for women and men. Such views indicate not only Vilar’s cleverness in presenting her material but the level of awareness of the subject in West Germany (and perhaps other nations?).

Before attempting to analyze why Vilar appeals to so many Germans, it is necessary to analyze the book itself, and entangle its premises and prejudices which evidently are not limited to Vilar’s understanding (or misunderstanding) of the subject. Abstracted in one-paragraph form her ideas are absurd. However in the longer context of the book, they are more difficult to pin down. One of the main factors of her appeal lies in the clever joggling of well-known themes.

Villas and children and dogs = paradise

In the opening chapters Vilar makes clear she sees women as a social class, in opposition to a second social class, composed of men. The dominant class-woman exploits the helpless class-man. (“What women do to men places the entire capitalist system In the shadows.” Interview with Konkret Magazine, June 16, 1971).

Men are strong, intelligent and full of imagination. They are part of an encompassing system which forces them to work in order to support women. With the exception of two references in the 200-page book, Vilar’s man appears in the role of factory-owner, financier, shipper, corporation manager and even president of the United States.

His wife who exploits him, by definition is no worse off financially: “(She) spends her days under paradise-like conditions in a comfortable suburban villa in the company of children, dogs and other women, decked out with two cars…(and) tells her husband, who is perhaps an engineer or lawyer, that she envies his fulfilled life…and he believes it!”

Vilar wisely refrains from illustrating her theories with people who may not be well-situated in society, mainly because the contradiction in her concepts would be easier to spot. By this method however she eliminates more than 50 percent of the population in advanced western nations alone. Yet nowhere does Vilar pretend she is not speaking for ALL men and women, or at least the majority of the population.

To continue. Vilar describes woman as a half-person who never thinks because she does not need her brains to stay alive. She forces man to work for her for the periodic use of her vagina.

Vilar’s first proof is a historical one, or rather examples which falsify history. She maintains the gains women have made in society are entirely due to the benevolence of men and thereby avoids giving any positive weight to feminist movements. It is analogous to saying workers were granted the right to form trade unions due to the intelligence of their employer and blacks gained their rights because whites were in a generous mood:

“Man realizes woman could not be satisfied with mere housework and “drags her to his universities under protest…gives her the right to vote…so she may change the system…according to her ideals.”

Ibsen’s Nora gave men such a shock they swore they would fight for human conditions for women. But women ruined it all by propagating stylish fads: They “masqueraded themselves as suffragettes”, then emulated existentialists and let their hair grow and then listened to Mao by ushering in the “Mao-look.”

Why? Because woman is like a corporation, a “neutral object, concerned only with profit. If a worker leaves her shop she is afraid – unless she can sign a contract with a replacement. Her love pangs are confined to the feeling that “a good business is walking away from her.”

Man on the other hand is “curious, thoughtful, creative, sensitive.” Yet he is constantly exploited by a parasitic clique which uses a primitive, but workable system of marriage, divorce, birth and life insurance to get at his money. As a result American women own more than half the private wealth in the country (this statement is used categorically without any differentiation among income groups or registration of income for tax purposes). “Soon instead of private power over men, women will have absolute material wealth.”

Vilar then attempts to explain how this situation came about, or rather why men submit to such horrors. She explains the “taming of men” through familiar and recognizable role training theories and avoids falling into the trap of attributing socialization of men and women to biological differences.

Little boys learn to play with building blocks, little girls with dolls. Boys are trained to be honorable and aggressive – and at the same time imbued with the knowledge they will one day support a woman, who can be as dumb as she likes. His mother is responsible for such training as it reinforces her position in the family. Girls are taught to follow her example, to devise methods to catch a man who earns a good living.

Boots = Sex

Such superior knowledge did not come to women by instinct but through years of historical practice. Somewhere in history women “discovered” their ability to bear children. It is this facility which they turn into a so-called weakness to dupe men (…”the fact Eve comes from Adam’s rib must have been invented by women.”), and hence a never-ending vicious circle is put into motion.

Women train men to want her children, in order to enslave them. Men want children also, but for different reasons – to justify their subjugation to women, and hence their tireless efforts to support her.

Sex also fulfills this double function. Women neither like not dislike sex, if they can squeeze in time for it between beauty treatments. Men on the other hand have been trained to be afraid of their potency and try to please woman without knowing their greatest pleasures lie elsewhere: dressing for a cocktail party, a new pair of aubergine patent leather boots, to name a few examples. However some sex is necessary to women – they need children.

“The Final Solution”

Women need children for economic reasons. If they really wanted them, they would adopt orphans, as the world is full of homeless children. Should this laudatory goal be accomplished, one can assume from Vilar’s theory that the human race in the next generation would have no need to reproduce itself:

“Almost every (woman)…can choose between a career and children and almost everyone of them chooses children…What will they do…when men discover…that one doesn’t need children at all to live?”

Ergo, Vilar finds a quick solution to the manifold problems of raising children, of apportioning time between child-care and work, etc. Her solution is none other than the final one. She also in the above paragraph places the emancipation problem squarely on individual self-will. She dismisses all obstacles society may place on the individual, while on the other hand maintaining that roll-training (particularly for men) determines people’s behavior irrespective of their will.

However Vilar does not neglect the working woman. Towards the end of the book this woman is decried as someone as dumb as the housewife but more dishonest. She uses her skills to raise her value of the marriage market.

Periodically she also organizes herself to complain about discrimination – without realizing that she IS incompetent. She does not really participate in a life-and-death competition on the job. She fights for women’s rights without understanding the blame is hers – “her dumbness, lack of interest, irresponsibility and eternal pregnancies.”

But the woman who does “make it” still fails to grasp the essence of life: “Men don’t work because they want to but because they have to.” Most men could use their intelligence to better advantage if they were free from obligations – as free for example as the housewife:

“As a rule, the woman in her suburban villa has a better chance to lead an active intellectual life than someone moving between typewriter and dictaphone.”

According to Vilar woman is damned if she works and damned if she does not. Men develop superior skills because they work and women because they do not. However Vilar’s ideal world is one in which men spend their day in isolation – like the housewife. We are back to square one.

Asiatics and cripples

Throughout the book, Vilar uses a battery of humorous examples to illustrate her theory. Many are not only accurate reflections of husband-and-wife scenes a la Blondie comic strips but timely and delightfully drawn. It is precisely because of this skill that her inaccurate theories and facts are often camouflaged and her ignorance, after 10 years of vigorous discussion on the issue, overlooked.

Vilar rightly maintains in numerous caricatures the new sexual freedom in the 20th century is used, more often than not, to buy security from men. But instead of searching for the reason for this economic dependence, she attributes it to laziness and guile. By this means Vilar points out distortions and disguises in women’s behavior (which Betty Friedan in the “Feminine Mystique” did as early as 1963) that bring no one’s understanding of the subject any further. Since her causes and origins are wrong, it is not surprising that her solutions are absurd.

But sometimes her tidbits are not so funny. For the sake of a gag she several times resorts to the unscrupulous – e. g. the fascist values of contempt for the weak and the sick, the racism in the Vietnam war, somehow are made to fit into the woman-man conflict.

For example, to illustrate the mystique of motherhood, Vilar maintains that giving birth to a blind or deformed child is a sure way to establish martyrdom.

To prove her real function in life, the mother then rushes to give birth to a “normal child…and forces this normal child to spend his entire youth, his whole life, in the company of a feeble-minded.”

War and the Vietnamese fare no better. To show women are not physically weaker than men nor more sensitive to the brutalities of war (their monthly cycle makes them used to seeing blood), the following sentence emerges:

“A North American woman, who was athletic during her school year, cannot for example be overpowered by the physical strength of the much smaller Vietnamese. A GI then fights, when he conducts a war against Asiatics, against an enemy who is no stronger than his college girlfriend.” (underlining mine.)

Having described some of Vilar’s more obvious weaknesses, it appears necessary to expand on some of her fundamental theoretical misconceptions. While I cannot claim to present a solid counter-theory in a few pages, I believe one cannot unravel Vilar’s thoughts (and those who agree with her) properly without indicating the direction of an analysis which would prove more fruitful for grappling with “the woman problem”. Broken down into rough categories, Vilar, in my opinion, has failed to understand the origins of the “‘woman problem”, the choices open to woman today, the role of work in society, and the value of organization.

Vilar Thesis One…

…women as a class early in history, perhaps as far back as Adam and Eve discovered the luxury of having men work for them. This situation developed into direct exploitation, into a conflict between the sexes that would “place the capitalist system in the shadows”…

Women and men cannot be defined as classes (and here I would disagree with some of the feminists also). Sex conflicts may have been among the first clashes in history but this doesn’t explain how or why society developed in certain directions in different epochs.

Classes (to cut short long definitions) are groups of people differing from one another by their relationship to society’s organization of production and division of labor, their relationship to the wealth of society, their place in certain strata of society. Classes can revolt, replace each other, form new amalgamations, disappear. Men and women cannot. One cannot replace the other or come in conflict with a third.

Nor do men belong to one social stratum of society and all women to another. A female school teacher is not less privileged than an unemployed male worker. Nor conversely is Vilar’s factory owner more exploited by his wife than he exploits his female employee. His wife also does not define her interests in solidarity with her maid rather than with her husband.

But this does not mean women do not have a specific form of oppression. Within each class in society there are differentiations and strata. And within these groupings women usually comprise the lower strata or caste: the lady of leisure has fewer rights and opportunities than her husband, the female factory worker may receive less pay than her husband employed at the same place, etc.

However, the status of women did not develop because of a great conspiracy of female guile and cunning, or because of promises of leisure.

Even a cursory glance at primitive communities reveals women were not dependent on men. In many early societies women were the mainstay of the communities, responsible for their organization, while men periodically visited with the fruits of hunt. Although women’s biological function of bearing children made them less mobile, this was not accompanied by a socially inferior status.

Societies grew more complicated and accumulated wealth. Inheritance, private property and landownership were introduced. The male hunter began to settle down in female communities and through coercion and force, slowly took them over. Along with a struggle over female communities, there developed a struggle over dominance of children (to prove man’s transcendence and pass on his wealth), for land, for possessions in general. Gradually a group of males achieved enough wealth and power to dominate the rest of the population, not only women but other men who became slaves.

To continue this historical trend (admittedly grossly oversimplified) by skipping to the age of feudalism, at which time the class and caste system was firmly established. Families lived in communal households comprising several generations. Work took place in the environment or near vicinity of the home and leisure was restricted to those few with servants. In general there was no separation of living and work places, consumption and production areas, in which both men and women divided up the chores.

When town life began to develop, it was logical for men (they did not bear children) who had greater mobility to seek a living away from the home. Women who tried to do the same and were organized into guilds were phased out of these jobs, particularly during the Reformation. Luther not only re-affirmed but brought additional vehemence to the Judaic-Christian tradition of women’s role in the home. In addition religious wars impoverished large areas of the countryside and employment was scarce for all. In central Europe restrictions developed limiting female employment to domestic chores. Women found work only as maids or as prostitutes.

With the growth of manufacturing and early industrialization, women’s place in the home and in the family altered severely. Now in order for the family to survive, large numbers of women and children were drafted into industry under the most brutal conditions, in sweat-shops or Britain’s quaintly-named “cottage-industries.”

In reality many women (and men) could not attend to the most minimal functions of raising a family. But the dominant ideology in society was one suited to a feudalistic organization of labor, and one which only the upper classes could abide by. It was a sign of prestige for a woman not to work, to fulfill her “natural” duties as wife and mother. Esther Vilar makes the mistake of confusing this ideology – what should be – with what was. As the reality did not coincide with the ideal a peculiar rationalization developed: women were working but being told they shouldn’t, and hence were paid less wages as they were only secondary wage earners – although the family could not support itself with one wage earner.

Essentially unskilled and semi-skilled laborers find themselves in a similar situation today. The ideology of the home is refurbished whenever women enter production. In every western industrialized nation, statistics show women employees on the average are paid less wages for the same work as men-or their job is often reclassified and given a different name, which amounts to the same thing. Unfortunately many women in this situation are a victim of the same ideology and believe their work really is worth less than a man’s.

As a middle-class developed, the relationship of women and employment took a different form. Many middle-income women found their tasks in running a household were dwindling, and the money in the family was no longer sufficient. Since only menial work was available to her, she began to demand education and skills and the right to decent work. This tendency is reflected in the 19th and early 20th century suffragette movements, which despite their laudable achievements failed to grasp the different attitudes toward work exhibited by middle income and lower-income class women.

The middle class woman demanded the right to work and equal rights with men in general while the working class woman wanted protection from work. The educated woman’s demand often resulted in special occupations (teaching, nursing, etc.) peopled almost exclusively by women and hence established as poorly paid professions, which nevertheless demanded training and education.

Thus, working class as well as middle class women were assigned an inferior role in society on the basis of their sex, based on a complex set of traditions and ideology which have their roots in epochs when both men and women spent most of their time in the home. While such discrimination cut through class lines, the form it took in each class differed immensely.

The housewife-housebound role of woman did not develop as a result of individual choice, an inferior brain or condition of luxury and leisure. While woman’s often-separate development from man can be traced to biological differences, her role in different epochs was foremost determined by the type of work which fell within the sphere of the family and how it was organized by society outside the family.

Vilar Thesis II…

…Woman today has a choice of leading a more productive life outside the home but chooses not to exercise it. She adheres to her role training in order to set up a life of leisure and make men work for her.

The problem is not that simple. No doubt the range of choices open to woman during the past half-century have increased immeasurably. However the feudal ideology (which sometimes passes under the name of role training of socialization processes) dies slowly. Not only men and illustrated magazines contend women belong in the home or at the hairdresser, but most women believe it also. But a sudden alteration of such subjective views, if this were possible, would only partly solve the problem.

Women’s dependency on man has roots in society which a good chat between husband and wife will not untangle. Unless the social, political and economic obstacles hindering emancipation for women (and men) are understood, psychological attitudes will be reduced to individual idiosyncrasies.

Firstly, Vilar is incorrect as defining housewives as creatures of leisure. Although a good number of housewives (those without children, or with wealth) do reach such a state of affairs, this is not the norm. Research institutes in the US and Europe have calculated that a woman with small children spends about 80 hours a week doing necessary work in the home. Without children, this work can be reduced to about 20.

The planning of nurseries, day-care centers and kindergartens is haphazard at best in providing enough places to meet the current demand. (West Germany is short 18, 000 kindergartens for five year olds alone). Nor have western European nations (or the US) given top-priority to such programs in their yearly governmental budgets.

Our societies also are not organized around a principle of part-time work as a norm for men and women. In fact the situation is the opposite. One member of the family (usually the woman) is expected to care for children and the home to leave another member of the family (the man) free to undertake employment. Her work is private and not counted as productive social work but yet forms an integral part of the organization of the production process.

Answers to the conflicts between mother and career are long and complicated, and are the subject of mountains of literature. Considering the time and energy so many people have spent in recent years tackling the problem of child-care alone, it seems scandalous for Vilar to evade the issue by proposing one shouldn’t have children at all – a solution as foolish as one which forces all women to breed.

Secondly, more than one third of all women of working age in western Europe and North America are employed outside the home. In Europe less than 10 percent of this group (the statistics are slightly higher in America) are in technical or professional positions. In West Germany’s highly developed economy, most women work in unskilled or semi-skilled factory jobs, menial service industries or low-paying clerical positions. It is not a very inviting prospect. As pointed out earlier, this situation is not accidental, or entirely a product of lack of ambition. Entire industries are constructed around cheap female labor (or cheap foreign labor, or cheap black labor) and rationalized through myths such as “women don’t need the money anyway”. (As if pay were determined on individual or family need).

But more important, if all housewives and unemployed women tomorrow decided to seek employment not even West Germany, which imports two million foreign laborers to fill job openings, would have enough positions to meet the demand.

The above bleak picture could make one wonder why women ever bothered to look for a job in the first place. But they do. Many work because they have no choice, they need the money. Others because they want to, because educational and job opportunities have increased in the 20th century in general. But a trend towards female employment is a far-cry from full employment.

However, most women do not feel themselves equal to men, or as Vilar says, regard their job, if they have one, as more fulfilling than their role as mother and wife. But if Vilar herself admits this attitude stems from childhood when little girls are taught, through praise and criticism, their career will be in the home, then some of this same praise must come from somewhere to produce the opposite effect. Where does training end and free choice begin? It is equally as fallacious to suppose that once women decided to move out of the home all doors are open to her, if she only took advantage of them, that the problem will go away without some basic restructuring of society’s goals, of the labor process itself.

Vilar Thesis III…

Men through their education and work acquire skills which help them lead a fuller life. Women idle away as housewives. But because she is free from financial obligations, she could, if she were not such a parasite, lead an intellectually full life at home – or allow her husband to stay home (while she works) to fulfill himself…

The above abstract is contradictory, even if one supposes all men have education and skills or have had the opportunity to acquire them. If the male sex attains such qualities through education and work, how can he also fulfill himself if he stays home? However Vilar does touch on the two-fold nature of work, even if in an upside down fashion. Much of the work in society is dull and meaningless, alienating, exploitive or whatever adjectives one cares to use. But the potential for training one’s mind, acquiring a social conscience, learning how to communicate with people or achieving economic independence does not come from isolation in the home, however pleasant or unpleasant housework may be.

Some of the negative traits among women which Vilar describes (reticence, lack of interest in public issues, etc.) develop precisely because of her work outside of society’s system of production, and not because as Vilar contends, she plays the part of the capitalist in the family and man, the proletariat. Employment is not only a route to economic independence, but a precondition (because it can lead to economic independence) toward achieving the self-confidence which would contribute to altering stereotyped roles of man and woman.

This is not to argue that employment automatically leads to emancipation, but isolated housework is a sure route in the other direction. Until women got their feet wet in the production process, they neither understood the nature of their specific discrimination nor the negative aspects of work for all people. (None of the women’s rights movements existed or could have until some women were drawn into the labor process.) If the roles were reversed as Vilar advocates – women worked and men stayed at home – the traits which Vilar condemns in the female would quickly become part of the male character. Furthermore, actions to change the alienating nature of work itself are doomed to failure if they do not involve the participation of people who are in the work process itself.

However, Vilar’s unpolitical approach to her subject is not a result of an attempt to limit her topic, but is basic to her theories and appears in her previous writings as well. It is most clearly revealed in her advocacy of a retreat to the world of thought and isolation as the best route to self-fulfillment. Although this trait is by no means confined to German middle-class intellectuals, the Germans have had a history of giving it ideological foundations.

Sociology professor Ralf Dahrendorf (currently Bonn’s representative to the common market) in his book, “Society and Democracy in Germany”, labels this development as the theory of the “inner immigrant” or the “romantic intellectual”.

He describes this, person as one who “likes to leave reality to its own resources to withdraw to the refuge of “truth”…This role…is defined in contrast to that of the actor, until it is safely removed from any contact with the dirty sphere of action….Scholars and artists, the much praised quiet man of the country, latter-day cultural pessimists and many others see to it that the romantic attitude remains a German interpretation of the role of the intellectual.”

While Dahrendorf does not exclude the need for man or woman to find time to work or to think in solitary, he attempts to analyze the consequences of theories which have developed into a fetishism of the ivory-tower: an unpolitical German intellectual who thought Hitler could not enter his inner immigration.

Vilar, in her previous work, an essay, “Die Lust an der Unfreiheit” (The desire not to be free) builds a case for such individual withdrawal. A conglomeration of “systems” (Nazism, Communism, racism, Catholicism) are thrown into the same melting pot to prove man clings to authority as a conscious act of enslavement. From this premise, it is a short step toward condemning all forms of collective action as a surrender of individual liberty.

Vilar Thesis IV…

Organizations (suffragettes, women’s liberation) are a passing fad to disguise a personal malaise.

Although Vilar’s contempt for women’s organizations is genuine, she is much less concerned with the goals of such groups than the fact organizations exist at all. This is clear in her entire approach to history, which is reduced to the granting and acceptance or rejection of favors, in this case between men and women. In “Die Lust an der Unfreiheit” she is more explicit on the subject of organizations which she claims are more often than not a substitute for parental authority. Again, the development of man is sold short for the sake of simplicity.

Major changes in history, whether positive or negative, are not only the result of accidental events, or uncontrollable historical developments. The form in which changes take place usually involves the active and conscious participation of people. Revolutions, political coups, the founding of a country are collective activities, organized efforts, which call for a bit more than parental rebellion.

One cannot advocate organization for the sake of organization as a panacea for all cures, or argue that all groups or movements are productive entities. But voluntary collective action is one of the few ways to prevent a political disaster or to bring about political change. Even if ultimate goals are not reached, collective action, which requires commitment and responsibility from participants, is a method of raising the individual’s consciousness and sophistication about the society he lives in. Those who theorize against or deny the right of assembly are often those who have the most to gain by the inactivity of others.

The situation in the field of women’s rights is no different. Whether women should join women’s lib groups is not an issue here as Vilar is more concerned with the motives for joining groups than the goals of the groups. However, in view of all the literature that has been published on this subject, it should be clear to the next person who writes a book that the woman-man conflict does not begin and end with a personal malaise. The problem of child-rearing, equal and proper employment cannot be solved by a rebellion of the individual among her or his friends. These issues are political and require political action, and political action needs organization.

Sociological Cabarets

Despite so many obvious flaws in Vilar’s theory it would be incorrect to attribute them en masse to her readers. Her book was timely, her approach simple and direct, her writing style is smooth and controlled. Unlike the United States, Britain and other countries, literature on women’s lib does not flood the bookstores in West Germany. The women’s movement is new, and made headlines only about a year ago (about the same time Vilar’s book was published) with an abortion reform campaign.

The word “women’s lib”, often used in German, is usually meant as a reference to the American movement – which in turn conjures up images of bra-burning, husband-beating, and uppity women lounging away in luxurious suburbia. In fact it is almost comprehensible to the average German that THE American Woman should find anything to complain about at all. However, the subject is not entirely new here. There is a growing curiosity about “Gleichberechtigung” (equal rights) and discussions in government circles or on television on the subject are no longer unique.

In the field of literature, however, information is paltry. Vilar has no competition. True, Friedan’s “Feminine Mystique” as well as Kate Millet’s “Sexual Politics” have been translated into German. (Juliett Mitchell’s “Women’s Estate” is available also – but in English only.) But Friedan’s work is geared to the American reader and Millet’s book is too lengthy and expensive for a first dip into the subject.

Among the German writers, up-to-date literature on equal rights or emancipation is usually confined to small intellectual magazines or deals with one area of the subject. I can think of only one new book in the past two years which treats the issue comprehensively: Jutta Menschik’s “Emancipation or Equal Rights?” Menschik wrote an excellent book but it is a thoroughly academic work, with limited mass appeal.

Vilar also broke into print with a publicity campaign, unrivaled by any other author writing on women in this country. When “Der Dressierte Mann” was first published in January, 1971, it received little attention and sold slowly. Reviews in the main were short and critical. The Frankfurter Rundschau’s verdict of “an insipid potpourri of after-cocktail conversation” was not atypical. “Der Spiegel” magazine, after an initial recommendation of the book, took another look at it and characterized its contents as “sociological cabaret.”

About nine months after the book was on the market, Vilar was interviewed on a high-rating television variety-talk show. Within a week of the program, she was besieged by journalists from various media, and her publishers had to print 200, 000 copies to keep up with the demand. Mass circulation tabloids featured a regular diet of Vilar and two serialized the book. Letters to the editor were printed at length, each batch producing a new batch and another center spread. In short, Vilar became a household word.

If the letters are any indication of public opinion, Vilar, despite her simplicity, is often misunderstood. She is criticized for being an advocate of women’s lib and quoted as a supporter of the status quo – although she neither approves of husband-wife relations the way they are or proposes political organization to change them.

The strongest criticism, immediately after the television program came from housewives, who felt both Vilar and what they have heard about women’s lib threatened their existence. Mrs. Hortense Keller of Munich wrote: “I would like to hit her…One can just imagine the dirt accumulating in her own home!”

Some of her warmest admirers were men and newspaper editors who have heard enough talk about women’s emancipation. They feel flattered by Vilar’s compliments to the male sex while at the same time would not be happy with a woman like Vilar. George Ferdinand von Hirschau of Passau said in a letter: “Vilar’s opinions are not shocking, but the tone of her critics is – those so-called well-behaved women!”

Another misreading of Vilar comes from energetic hard-working women, who are not included in Vilar’s discussion of the female sex. Mrs. Petra Finkel of Hamburg says she agrees with Vilar: “My family has six members and we manage the housework…After the children were older I went to work. I work nights and my husband works days. (One is tempted to ask Mrs. Finkel WHY she works nights).

One category of people, however, neither misunderstands or disapproves of Vilar – the woman (or man) very much like the author herself. This type of person has “made-it” by attaining a status job in a “man’s field”, or in an area usually closed to his or her class or race. Having reached some degree of success, he or she or he turns around and wonders why there were not more Horatio Algers. Among the women in this category, the initial reaction is usually a sneer at the housewife. She is automatically treated as sub-human, beyond the pale of understanding. Ursula Furth of Berlin is typical of this group: “I am a lawyer and want to become a judge….I know from my profession, from watching my friends that what Vilar says is…true.”

Yet one cannot underestimate Vilars impact among people favorably disposed to the subject and exploring it for the first time, Anneliese Blockard of Hanover explains at length how she spent hours discussing the book with her girlfriend, how what Vilar says “rings bells”. The discussions take hours, and as Miss Blockard admits, they took hours before she and her friend read the book. Like an ad in an illustrated, Miss Blockard adds: “I realized then the problem was inside me – nowhere else!”

Admittedly the book is a stimulating bestseller. But can one praise the absurd only because it is provocative?

Received in New York on May 16, 1972

©1972 Evelyn Leopold

Evelyn Leopold is an Alicia Patterson Fund award winner. This article may be published with credit to Evelyn Leopold and the Alicia Patterson Fund.