Caught in a thicket of ancient enmities, the Continental Divide National Scenic Trail stops here in northern New Mexicos Piedra Lumbre basin – a river valley of silvery cottonwood, yellow tipped sage and deceptive serenity.

Once completed, the trail will be the longest transcontinental trek in the U.S. The tranquil beauty of the Piedra Lumbre, flanked by the burnt umber battlements of the Canjilon Mountains would make for one of the most scenic passages along the 3,200 mile route.

But the people who inhabit this valley do not want a trail threading through land they have clung to jealously since Philip III of Spain left their ancestors here to deal with harsh winters, hostile Indians and a succession of Yankee profiteers.

Northern New Mexico is crisscrossed with trails, its destiny is bound up with them. The Camino Real from Mexico brought Juan de Onate, the explorer who escorted the first settlers in 1598.

In the early 1820s, the Santa Fe Trail brought fur trappers who wiped out the beaver, pocketed the profits and awakened the young nation to the rewards of westerly expansion. In 1846, Col. Stephen Watts Kearny and his Army of the West marched down the Sana Fe Trail to stake America’s claim to all of New Mexico.

The Continental Divide Trail is the most challenging of 19 national scenic and historic trails that follow the footsteps of famous explorers. All together, the trails extend across more than 30,000 miles and attract millions of visitors, but they are not always a hit with the people who live along the way.

“Whatever it takes, we are going to stop it from coming through our community,” said Moises Morales, a Rio Arriba County Commissioner who sees the coming of the Continental Divide Trail as yet another chapter in a bitter saga of trespass and usurpation.

In northern New Mexico, today, many people tend to regard a stranger with a backpack not a whole lot differently from the buckskin adventurer of old. The modern explorer covets the scenery the way the frontiersmen lusted after beaver hides, turquoise and timber. The result is often similar. A resource is exploited. An outsider benefits.

For more than 30 years, Morales has been a leader in an occasionally violent struggle to regain control of millions of acres of ancestral lands. Much of it was lost to speculators who made their way down the Santa Fe Trail in the years following the war with Mexico.

In recent times, Morales and other land rights activists have clashed with promoters of ski resorts, second home develop- ments and conservation groups who want to ban livestock from pastures that were once part of a vast commons where sheep and cattle were free to roam.

As Morales sees it, a well-publicized national scenic trail is a vector for alien values – in particular, rural gentrification and environmentalism.

“Who’s got time to walk a Continental Divide Trail? Just rich people and tree huggers,” he asked. “First thing you know, they are complaining about our cows, or trying to buy up our land.”

Moreover, he said, the trail would funnel a steady stream of unwanted tourists past secluded communities, mountain meadows and moradas – the mud sided houses of worship used by the Penitentes, the secretive order of Catholic men established after the Catholic Church all but abandoned these villages in the 18th century.

“We are not interested in satisfying a tourist’s curiosity,” Morales said. “Our villages are not stage sets.”

Northern New Mexico is an impoverished stronghold of ethnic traditions unique in America. Yet, the people here are not alone in their resistance to a new west where recreation and real estate fuel an economy once powered by chain saws, drill rigs, dynamite and men on horseback.

Two-thirds complete, the divide trail is a potent symbol of the changing scene. It is also a testament to Americas enduring appetite for the spiritual and material rewards of high adventure.

Like the westward trails that preceded it, this one has the backing of businesses, including about 25 outdoor equipment companies, who believe the market for mountain recreation could easily rival the fads for animal furs and mineral wealth that lured the first trail blazers across the divide.

Twenty years in the making, the trail, which will lead from Canada to Mexico, was conceived as a wilder, longer and more daunting version of the Appalachian Trail.

The Divide Trail goes through five states, three national parks, a dozen wilderness areas, and 20 national forests. It passes ghost towns, battlefields and forts and skirts the summits of 14,000-foot mountains.

Tracing the crest of the Rockies, the Continental Divide marks the parting of Americas western watershed. Moisture spilling off the west flank of the range flows to the Pacific Ocean. From the east side of the range water flows to the Atlantic.

But the country along the divide is also riven by social and ethnic tensions that have set people against each other ever since a member of the Lewis and Clark expedition killed a Blackfeet Indian near the Continental Divide in northern Montana in 1806.

Today, as the architects of the trail attempt to negotiate rights of way across old land grants, grazing allotments, mining claims, oil fields, Indian reservations, ranches and new subdivisions, the project has become a sounding board for a larger debate over who controls the area’s magnificent natural resources.

At stake are water and property rights, native sovereignty, the future of open space and wild animals, the survival of cowboy culture and the ability of places like Rio Arriba County to preserve their identity against an onslaught of new people and new money.

Driving the debate is a fear of rural diaspora in a region that has been undergoing the most intense urbanization in the country for the past decade.

The trail has gotten snagged in the underbrush of regional politics, despite our efforts to avoid controversy, said Bruce Ward, who with his wife, Paula, heads the Continental Divide Trail Alliance, one of two organizations promoting the trail.

Road blocks have gone up in Colorado, Wyoming and southern New Mexico. But most of the obstacles are small compared with the cultural minefield that must be negotiated in Rio Arriba County.

The specter of dispossession has hung heavy here since the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo which ended the war with Mexico in 1848.

The treaty annexed much of the Southwest to the new American empire, but it also assured the people of Hispanic descent who were already living there that the land grants made to them by Spain and Mexico would be honored by the U.S. Government.

In the years following the treaty, however, Congress and the courts, perplexed by vague boundary descriptions and overlapping claims, balked at validating many of the land grants. The hesitation left many of the old claims in limbo. Cash poor Hispanic settlers, who neither understood English or the American legal system, became easy prey for speculators and their allies in a predatory frontier judicial system.

In Rio Arriba County, nearly 60% of native land claims were invalidated.

Eventually, more than two million acres of the disputed land wound up in the hands of the federal government and now makes up a big portion of the two national forests in Rio Arriba County. That acreage, which encompasses virtually the entire route of the Continental Divide Trail through northern New Mexico, is a principal target of land grant activists.

The struggle to reclaim these lands began in the 1880s when a group of hooded night riders, Las Gorras Blancas (the white hats) protested the loss of ancestral land by cutting fences, burning haystacks, barns and houses.

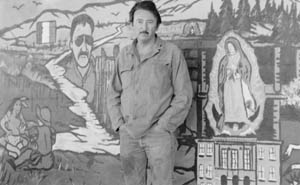

Today, the unofficial headquarters of the land rights movement is the MM Auto Repair shop beside U.S. Highway 84 outside Tierra Amarilla in northern Rio Arriba County.

MM stands for Moises Morales.

“These lands are going to be given back to us,” Morales insists, “and we’re going to get damages. The government has made millions of dollars off the forests though timber contracts and oil and gas royalties, and they have given us crumbs.”

Morales was part of an armed insurrection on behalf of the cause.

A mural on the wall of his auto repair shop tells the story. Painted by local highschool students, it commemorates the day 32 years ago when Morales and 19 other members of the Alianza Federal de Mercedes – loosely translated, the federal alliance of land grant heirs – waged a brief but bloody gun battle with sheriffs officers on the steps of the county courthouse.

The Alianza had gone to the courthouse to confront a district attorney who had been breaking up the group’s meetings and arresting its leaders.

Morales turned himself in after the shoot-out and eventually served time in jail.

But he did not give up right away. For several days, he hid out in the mountains, eluding troops and tanks of the New Mexico National Guard, called in by the governor as part of the largest man-hunt in the state’s history.

Morales escaped by following logging roads and stock trails that now make up a portion of the proposed route of the Continental Divide Trail.

He said he spent two rainy nights along the route, sleeping under trees, before braving 10 miles of open country across the Piedra Lumbre to a safe house owned by a farmer, Ubaldo Velasquez, who was an Alianza sympathizer.

Velasquez still lives in the same house and at 80 years old still believes that the lands of the Piedre Lumbra should be given back to the heirs of the land grantees. He claims to be one of them.

From an old brown chiffonier, he produced a raft of documents, copies of grants and surveys and genealogies reinforcing his assertion that his family was among the original recipients of the land grant when it was made by the Spanish territorial governor in 1766.

Although the courts have rebuffed him countless times, he continues to petition, hoping he will live long enough to find a sympathetic judge.

Meanwhile, a developer has acquired several hundred acres of the Piedra Lumbre. The land has been subdivided and fenced, blocking the old cattle trail that Velasquez and his neighbors used to lead their small herds to summer pastures.

“I got rid of my cattle,” Velasquez said bitterly. “It was going to be too expensive to trailer them over there, which is what we have to do now.”

No homes have been built yet in the new subdivision, and Velasquez still takes pleasure in looking out over the unblemished landscape.

To get the best view, he maneuvers his old pick-up truck up a dirt track to a knoll above his house. Back lit by a flaming sunset, the terraced uplands of the Piedra Lumbre glow green and orange like the gaudy layers of a child’s birthday cake.

The painter, Georgia O’Keeffe, who lived in this valley and immortalized the landscape, called it a “wonderful emptiness.”

Velasquez pointed to a spot in the foreground where two rivers, the Rio Puerco and the Rio Chama, converge. “There. That’s where they are going to build. People from California, Texas, New York, all over.”

“They are building on our land.”

©2000 Frank Clifford

Frank Clifford, a reporter for the Los Angeles Times, is researching the Continental Divide trail.