MOSCOW–At the time of his death in early November, Leonid Brezhnev was being offered a hero’s farewell if he would step down willingly and bring Communist Party politics one step closer to stability. That a smooth transition to party secretary by Yuri Andropov occurred even without Brezhnev’s retirement indicates a prior deal and a dramatic advance.

The jockeying for the Brezhnev succession began in earnest in January, 1981 with the death of Mikhail Suslov, the party’s Stalinist conscience. Konstantin Chernenko, a Brezhnev crony, initially inherited Suslov’s mantle as the Communist Party’s chief ideologist and keeper of the faith when he stood next to Brezhnev at Suslov’s memorial service and then next to Defense Minister Dmitrii Ustinov at May Day ceremonies in Red square. Chernenko read Brezhnev’s message to a conference of Party officials in the armed forces and he took over ideological functions, including an urgent effort to put the Party back in touch with grassroots public opinion in the provinces in order, so the leaders assume, to prevent a Poland from happening in Russia.

Despite these successes, Chernenko never mustered the credentials of Andropov, long the head of the KGB, who, in March 1982, moved to the secretariat of the Communist Party Central Committee, which oversees the country’s daily business.

Meanwhile, the KGB was taken over by Vitalii Vasilevich Fedorchuk, who is not considered a Brezhnev protégé and, equally important, was not a member of the Soviet politburo. This left Andropov still in control of the KGB. Chernenko’s eclipse in the light of Andropov’s rise reflected a weakening of Brezhnev’s role in his last days running the Kremlin. Rumors in Moscow all year contended that Brezhnev worked only two hours a day while intrigue and strategic positioning for his succession danced a merry minuet in the background.

What little is known about Andropov centers around his role in running the KGB. Such a position allowed him to exert extraordinary influence in the Kremlin without becoming a public figure known in the West. Indeed, the mystery surrounding him is tinged with the intrigue and distaste associated with the arbitrary and cruel excesses of the Soviet secret police.

He is a worldly man who is expected to continue the stagnant consensus of Kremlin politics but the authority and speed with which he took over the Party indicates a vigor to tackle the country’s greatest problem, its economy.

The new Kremlin leadership clearly faces a choice of maintaining the same ideologically hidebound policies that have prevailed since Lenin or modernizing the country as the needs of the contemporary world require.

Following the progressive stagnation of the Brezhnev era, the Soviet Union seemed impossible to move, but it has an unparalleled opportunity to transform its income from oil and other minerals into the engine for moving the country into the late 20th century. The revolution in the price of natural resources in the 1970s affected gold, platinum and diamonds as well as oil, coal and natural gas. The Soviet Union has all of them. It is perhaps the best endowed country in the world in the depth and diversity of its resources.

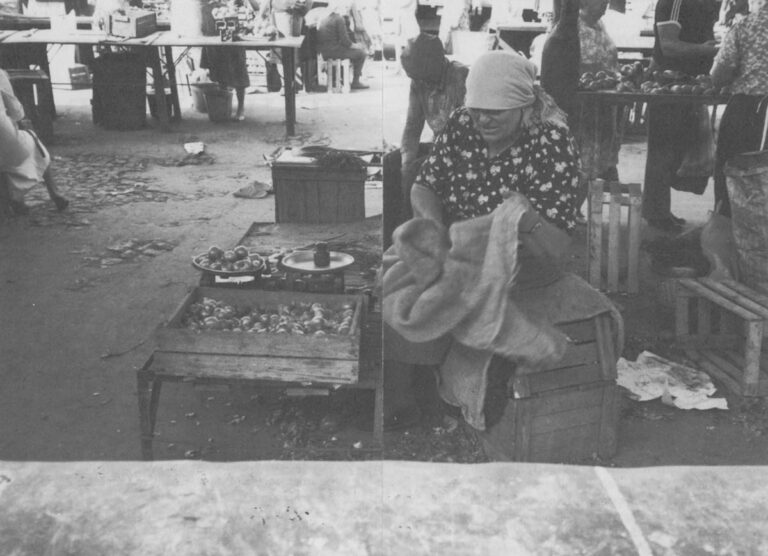

But these endowments have not prevented the Soviet Union from suffering painful economic contractions through the last years of Brezhnev’s rule. The evidence of economic decline is easy to see on the streets of Soviet cities. Even Moscow, which is supposed to be the showplace of Soviet achievement, can boast only long queues in front of shops that have any food or reasonably priced durable goods. There is so little available in the countryside that four million people come in to Moscow daily to buy food in the capital.

Soviet economic performance reached a new post-war low in the first half of 1982. The 2.7 percent growth rate in industrial production is the smallest since the Second World War and contrasts with a planned annual rate of 4.7 percent.

Oil and chemical production have slowed to levels that put them in the category of such other stagnant Soviet industries as iron, steel, automobiles and, among consumer goods, leather shoes and refrigerators. Besides a sharp retreat in the production of computers and advanced machinery, there was no growth in agriculture and a decline in rail freight.

If these reversals in the Soviet economy give comfort to American foreign policy advisers, they should also be an incentive to take advantage of the needs of the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe alike.

The west should be enthusiastic supporters of economic development within the Soviet Union. Modern economies are built on improved communication and sophisticated machinery that cannot be ruthlessly controlled from above. American corporations long ago learned the value of decentralized decision-making, a process that in the Soviet Union will have to entail not only autonomous managers but also autonomous contracts between suppliers and buyers to guarantee both delivery dates and quality control on products. There is no way for the Soviet Union to get a modern economy without loosening political ties in favor of economic decentralization and, indeed, the reversal of lines of authority to allow economics control over politics.

Trade, which the United States recognized as its best weapon to fight Communism after the war, is equally important today. With its continued enthusiasm for the gas pipeline to western Europe, the Soviet Union joins the rest of Eastern Europe in its efforts to develop trade relations across the ideological frontiers.

Indeed, the Eastern Europeans have taken the lead in breaking down those barriers. Nothing is more indicative of Eastern Europe’s desire for better trade relations with the west than Hungary and Poland’s desire to join the International Monetary Fund. It is the one substitute for Soviet economic aid available at a time when the Soviet Union is less willing to subsidize their economies.

It is a development that should be heartily encouraged. After all, the cold war resulted from the Soviets’ cutting Eastern Europe off from western trade. There was a time when the United States invited the Soviet Union to join the Marshall Plan and get American economic aid in return for deciding on a recovery plan that America would supervise. Moscow backed out and took Czechoslovakia with it, an event that seemed to bring the iron curtain down with a thud.

Joining the IMF is nothing less than a reversal of early post-war history. It signifies the enduring value and superiority of America’s recovery program to the Soviet alternative, which was little more than a way for the Soviets to exploit more developed economies until those economies were being subsidized by the Soviets. Stalin helped push Eastern European economies into the Soviet mold of the inefficient production of heavy industry, using Russian raw materials and crude production quotas that emphasized the quantity rather than the quality of finished goods.

In an increasingly sophisticated world economy, where intensive production of unique or at least modern goods is replacing extensive production of nineteenth-century technology like steel and heavy machinery, the Soviet economic model does not work. Even the Soviets have to recognize such deficiencies to improve their economic performance.

For the time being, while they try to patch over their problems with income from raw-material exports like oil, the Kremlin has to come into the net of world trade. The craving for so-called “hard currency” is an unacknowledged admission that the heavily inflated and deteriorating Eastern European economies cannot sustain the value of their own currencies. To trade with the west, all the Soviet Union has of real value is oil. That it is willing to trade that oil for “hard currency” is an important breakthrough in the reconciliation of the Soviet Union with the rest of the world. It is nothing less than an admission of defeat in the economic competition between east and west.

The American policy of a trade embargo not only hurts the American economy but also turns the moment of victory over the Soviet Union into a defeat of the conflict it engenders between the western allies.

The United States’ trade embargo against the Soviet Union has also given the Soviet leaders an excuse for economic problems that would have existed anyway and now lets them lay blame on war-mongering Americans. To the amusement of astute listeners in Moscow, Soviet radio broadcasts fulsomely praised Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s refusal to allow British companies to abide by the American embargo. Only weeks before, Britain and Mrs. Thatcher were being blasted as neo-imperialists for their defense of the Falkland Islands.

End of Détente

Such hypocrisy and unashamed opportunism do not make for ribald amusement, but it is about as much joy as is visible today in the Soviet Union, a country that is economically and politically beleaguered by both its enemies and its allies. For the average Soviet citizen, conditions have been deteriorating over the last five years. The end of the vestiges of détente with the United States brought a sudden slamming of the door on fresh winds from the west. A 26-year-old Leningrad worker deeply regrets the loss of contact with the outside world, which Soviet citizens barely hear about, let alone get to see for themselves.

“In 1970,” said the man in Leningrad, “a girl in my class was leaving for Israel with her family. The rest of us thought they were moving into the desert.”

Détente made the west more real as well as more appealing to the average Soviet citizen. His own poverty and lack of freedom were no longer accepted as the norm, but merely as the Soviet form of oppression that looks anachronistic from a western perspective.

The renewal of the cold war cuts off the chance for comparison just at a time when the Soviet life style is deteriorating. American policy-makers attribute the change to harsher terms imposed on the Soviet Union. In fact, more fundamental shifts are at work that are being obscured to the outside world. The Soviet Union is undergoing its own form of accommodation to a changing world economy. Poverty and repression are one side of the equation, but they are subject to improvement if the Soviet Union follows through on its growing ties to western economies and its intentions to improve the Soviet economic performance.

Dissidents claim that 1982 marked the nadir of civil liberties with the country. In past years, an open letter to foreign professional organizations protesting conditions in the Soviet Union would have brought reprimands. Now they are more likely to be greeted by prison terms of three to seven years. The Soviets cut telephone lines to the west and the new KGB head has moved to eliminate dissidence within the country by means more ruthless than have been seen in years.

These are signs of growing sensitivity within the Soviet hierarchy, an understandable development in light of the delicate maneuvering and changes going on with the country’s allies. Through the post-war period, it traded its natural wealth to its Eastern European partners in return for finished products which were often made from the Soviet raw materials.

The Russians tended to remain the creditor of its trading partners, especially as the price of oil rose in the west and slowly forced up the price even within the Soviet trading bloc, COMECON (the Council of Mutual Economic Assistance). The official COMECON price for oil was the average of the previous five years’ price on the open market.

During the period of stable oil prices until 1973, the Soviet Union benefited as much as its partners in the oil arrangement since the Russians had a secure market and the partners a secure supply. As with most of its intra-COMECON trade, oil represented a clever form of Soviet imperialism, in which the economically more backward but rich (in resources at least) country was the colonial power.

Reversing the pattern of traditional European colonialism, in which the colonizer took raw materials from the backward but rich colony, the Soviet Union controlled the output of its raw materials by controlling the advanced countries in which they were made. Czechoslovakia and East Germany in particular were economically advanced countries that could make good use of Soviet raw materials. In return the Soviet Union got finished products, but since finished products normally commanded better prices than raw materials, the Soviets had the political clout to prevent their being the exploited country.

In fact, in the mid-1970s, the Soviets were the exploited ones because oil was being brought so cheaply by the rest of Eastern Europe.

Now Moscow is changing all that, but probably too late to make up for the spectacular windfalls that Eastern Europe got through most of the 1970s. The Soviets have begun to cut back on subsidized oil exports to Eastern Europe. In return, they want to send their natural resources to Western Europe, where the world market price prevails and the Soviets can make a lot more money.

Until the Soviet Union changed its mind, Eastern Europe used cheap oil and other raw material supplies from the Soviet Union, to underwrite its growing trading with the west. While Eastern Europe’s trading deficit to the west had fallen to $3.7 billion in 1980 from a high of $6 billion in 1976, the bloc’s trading deficit to the Soviet Union had increased to $23 billion, according to the United States Defense Intelligence Agency.

Now that the Soviet Union has made across-the-board cuts in subsidized oil deliveries to Eastern Europe, its trade surplus has jumped from an annual average of 815 million rubles in the years from 1975 to 1979 to 1.8 billion rubles in 1980 and a record 3.1 billion rubles in 1981. Wharton Econometric Forecasting Associates, Inc., which keeps track of centrally planned economics, estimates that the Soviet trade surplus might reach 4.5 billion rubles in 1982 on the assumption that the terms of trade of Eastern Europe with Russia will deteriorate another 6 or 7 percent this year.

Renewing the Promise

As the long postwar period of Eastern Europe’s dependence on Soviet raw materials comes to a sudden halt, the United States has an ideal opportunity to renew the promise and achievements of the early postwar years. Then, Americans and Europeans alike were worried about the loss of all of Europe to Communism. That threat was turned back through economic help and reliance on democratic forces within Western Europe.

The Soviet Union can feel complacent about its hold over Eastern Europe only because the United States has not exhibited any interest in wooing Eastern Europe toward the west. Even if America recognized the possibilities in Eastern Europe, which apply foremost to Hungary’s growing economic ties to the west but is equally applicable to other countries worried about their faltering economic performance, the Soviet Union is not likely to pull another Stalinist stunt of stopping the changes because it is unwilling to shoulder the burden of the countries’ economic problems.

And for the west, the mechanism of the IMF can be used to help countries willing to bring their economies into line with the demands and obligations of such institutions as the IMF. Eastern Europe, and the Soviet Union for that matter, are prime trading partners. In the words of a Control Data Corporation official who has long traded with Eastern Europe and Russia, “The socialist countries are the best untapped markets in the world.” Western Europe has recognized the value of trading with Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union. The United States stands in jeopardy of losing its allies as well as its potential trading partners by ignoring this crucial opportunity.

©1982 Frank Lipsius

Frank Lipsius, feature writer on leave from the Financial Times of London, is studying the neutralization of Europe.