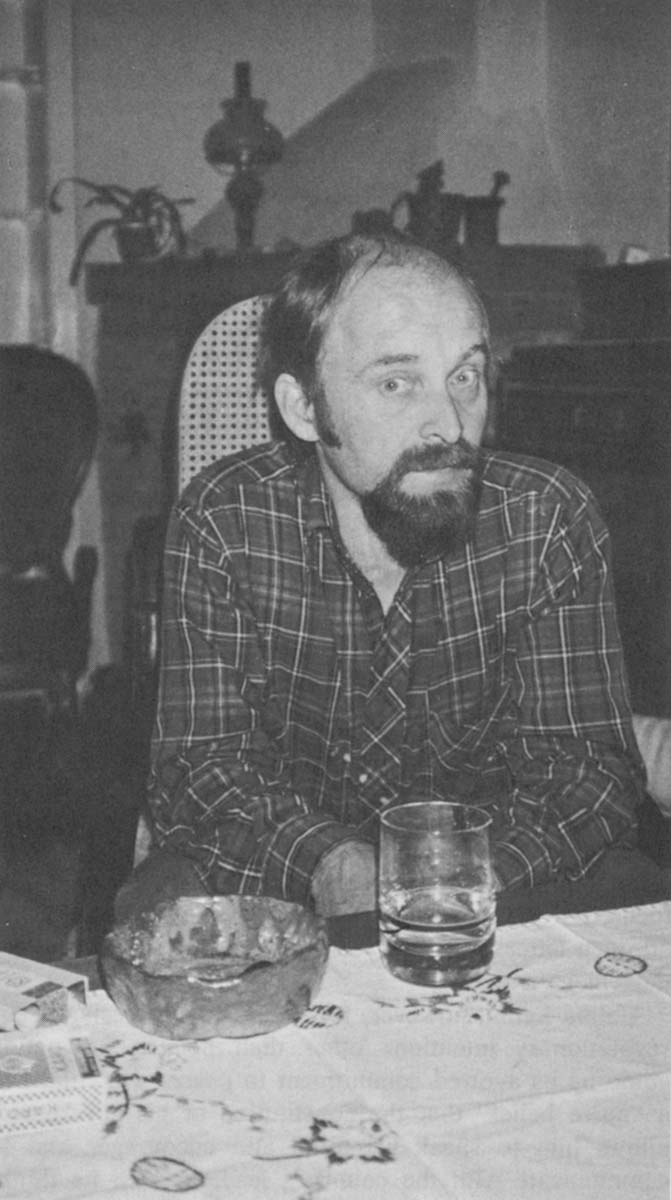

EAST BERLIN–Hunched over an ashtray in his comfortable living room in the northern suburbs of East Berlin, Reverend Reiner Eppelmann looks like nothing so much as a youthful version of Lenin, complete with penetrating eyes, balding pate and goatee.

He speaks softly but to the point, aware that his short “Berlin Appeal” which called for the removal of foreign troops and arms from both East and West Germany had focused world attention on him. The appeal, written as an open letter early this year, got the East German peace movement underway.

Unlike Lenin, however, Rev. Eppelmann disclaims any revolutionary intentions other than helping his nation abide by its avowed commitment to peace. He admits to a “naive belief” that the constitution of his government allows him to speak his mind and encourages him to communicate with the country’s leaders when he thinks they can use his counsel in the pursuit of their peaceful intentions. “I believe that the government is sincere in its profession of peace,” says the Evangelical Lutheran church pastor, “but like the United States or West Germany, which also extol their peaceful intentions, what they do does not always promote peace.”

Rev. Eppelmann knows he is playing a dangerous cat and mouse game with one of the most repressive regimes in Eastern Europe. He admits that “I expected to be in jail for a couple of years” and feels that he was released after two days only because of the pressure put on the East German government by the Soviet Union. He assumes his phone and house are wiretapped but, he adds with quiet pride, “I told the secret service that I would speak with anyone who asked me.” He also believes that publicity gives him some measure of protection, as does the church within which he operates.

In his first interview since being released, Rev. Eppelmann said that the Soviets got him released because “they want to keep the West European peace movement strong, and so they have to encourage us–to a point.”

Just how far remains an open question, since the East German peace movement, like its counterparts in other Eastern European countries, has been breaking new ground from its beginnings earlier this year with Rev. Eppelmann’s own “Berlin Appeal.” Written with Robert Havemann only months before the Marxist philosopher’s death in April, it was originally signed by 30 people but as many as 800 East Germans are thought by now to have subscribed to it. Besides the disarmament of the two Germanys, it calls for a general demilitarization of East German society, a subject that worries the authorities for going beyond the bounds of a peace movement into general discontent and potential subversion.

Rev. Eppelmann says that he spent a good deal of the two days of interrogation assuring the major who was questioning him that he had no intention other than promoting peace in East Germany. But the authorities are undoubtedly apprehensive about the influence of this counselor of East German youth whose voice is magnified through his small parish church in East Berlin and his highly popular “blues services,” which attract as many as 6,500 people from all over East Germany to listen to peace songs criticizing the Russian invasion of Afghanistan and other subjects rarely heard beyond the Berlin Wall.

Besides arresting Rev. Eppelmann to warn less brave East Germans of the danger of the peace movement, the East Berlin government has also cracked down on the wearing of peace armbands which had been distributed by the Evangelical Lutheran Church earlier this year. Though the authorities can feel safe in their arrest of a defenseless pastor, they did not anticipate the church’s angry reaction to what church leaders perceived to be a humiliating about-face by the government. Relations between church and state deteriorated to their lowest point since the original reconciliation that brought mutual tolerance and some independence to the church in 1969.

Indeed, the church is the only voice that exists outside the state and communist party in East Germany. Until the crackdown on the “Swords into ploughshares” armbands, which ironically depict the eight-foot-high statue of that name given by the Soviet Union to the United Nations in New York, the church had been a pliant partner to the state’s domination of East German society.

A Widening Rift

But it is now possible that the peace movement is the first fissure of a widening rift within East Germany. The church is concerned that should it buckle under government pressure now, it will lose the allegiance of the country’s youth, which have flocked to the church as the one alternative to an increasingly militarized East German society.

The church hierarchy made its most outspoken public statement in an Easter letter read in all East German Evangelical Lutheran churches, which claim the allegiance of 8 million of the country’s 17 million people. In the letter, the bishop of Magdeburg, Rev. Werner Krusche, allied the church with the country’s youth, claiming, “We fear that the actions of the state bodies are leading to difficult problems in the relationships of basically well-intentioned youth to the state and for the inner peace of our society and the personal development of young people.” The bishop of East Berlin, Rev. Gottfried Forck, thanked the young people “who maintained their genuinely peaceful conviction in spite of all the difficulties that have developed.”

Rev. Eppelmann applauds such actions by the church, which he feels holds the key to the future of the East German peace movement. Western interpreters have been confused about whether the church hierarchy has inhibited or sheltered pastors like Rev. Eppelmann. He has nothing but appreciation for the church’s support. They intervened on his behalf at the time of his arrest and he willingly acceded to the church’s demand that he refrain from being interviewed until now.

“My safety depends on two shields,” he said in his quiet and cautious manner. “The church and publicity. Robert Havemann (who spent many years under house arrest in East Berlin) showed that having just one of those shields is not enough.” As for the restraints that the church imposes, he contends that “differences are inevitable. If their perspective and ours were the same, one of them would be wrong. They have a dozen cups to look after,” he added metaphorically, “while I have only one.”

Using a beer bottle, an ashtray and two cigarette packets, he represented the church as being between the people and the state. He felt his role was to help move the church further toward the people and away from the state in representing the mass of East Germany society. Only the church is capable of promoting a meaningful alternative to the military draft, objecting to the use of realistic war toys like hand grenades in East German kindergartens and stopping the civil defense rehearsals that realistically portray the explosions of an atomic bomb on East German cities, a regular government exercise that makes war appear all too normal-and winnable.

Before it started, an East German peace movement seemed as unlikely as a voluntary demilitarization of the society by its aggressive and Stalinistic leaders. But having found a voice and brave souls like Rev. Eppelmann to lead such events as the peace forum held in Dresden with 5,000 young people in February, the advocates of peace in East Germany have advantages that do not exist elsewhere in the socialist bloc.

As Rev. Eppelmann noted, he can get all the publicity he needs from West German television, which is beamed to most of East Germany and becomes the broadcasting voice of unsanctioned East German opinion. Earlier this year, before the East German government started cracking down on its own peace movement, the West German peace movement was extensively covered on East German television. Now, it can still be seen on West German TV and, as Rev. Eppelmann admits, it helps fuel the flames of East German peace advocacy, just as he believes his public support encourages the West German movement.

The other peace movements of Eastern Europe are more isolated, but they too are beginning to be heard and almost by osmosis seem to have much in common with the East Germans.

The church seems to be the focus of protest, especially in Hungary, where a number of priests have been arrested for refusing national military service and advocating pacifism. While the Evangelical Lutheran church has been most active in Germany, it is the Catholic Church that has taken the lead in Hungary. But in Hungary the church leadership has deplored, rather than defended, its peace advocates, a difference that has as much to do with the discipline expected of the priests as it does with the attitudes of the church leaders themselves.

A recent underground publication in Hungary indicates a growing restiveness among young Catholic priests who have more to protest than the church’s acquiescence to government peace policy. They indict the church for all its compromises with the Hungarian state, using the reform-minded Second Vatican Council as the authority for rejecting all forms of illegitimate authority. While the sweeping condemnation is largely confined to church-state relations within Hungary, the peace movement is one area that goes beyond church doctrinal policy and encompasses an issue that could spread throughout Hungarian society.

The repressive regime of neighboring Czechoslovakia has witnessed a similar wave of Christian activism that has tangential links to the peace movement. While the Dutch Interchurch Peace Council received a telegram of support from the Charter 77 dissident movement in Czechoslovakia, itself an unusual development in the links between peace movements in East and West Europe, it is through underground church revivals that peace is making inroads throughout Czech society.

Even though Bibles have not been available in Prague for a year and a half, there is an underground distribution of religious literature that has landed at least 26 priests and 15 nuns in jail. Some claim the number of those imprisoned is much higher, and an amalgam of religious and peace movements is expected to foster peace initiatives within Czechoslovakia as has occurred in Hungary and East Germany.

Hundreds of thousands have openly demonstrated in Bucharest, Romania, against both superpowers and their militaristic foreign policies. But like the five million signatures the Soviet Union sent as a protest to NATO in Brussels, this demonstration was part of an “official” peace movement. Unlike the official peace movements in the rest of Eastern Europe, at least the Romanians took both sides to task for their threat to the peace, and very existence, of Europe. Such an ostentatious display of independence has long marked the foreign policy of Romanian president Nicolae Ceausescu. The two weeks of demonstrations that included a march by 300,000 in the middle of the Romanian capital provides encouragement to the unofficial movements elsewhere in Eastern Europe.

The crucial thrust for an East European peace movement depends of course on developments in the Soviet Union. While the Soviets may have forced the East Germans to be lenient with Rev. Eppelmann in East Berlin, there is no indication that an independent peace movement would be tolerated in the Soviet Union itself. The first effort, made by 11 Soviet citizens in early June, quickly led to their arrest and interrogation. Like the other countries of Eastern Europe, the Soviet Union claims to represent as much of a peace movement as their societies need or should have.

The government professed its espousal of peace before the world church gathering which Billy Graham attended in the spring in Moscow. The Soviet party paper Pravda led a three-day symposium of communist-party papers in 67 countries on ways. to encourage “the struggle for peace and détente.” And five million Soviet young people were reported to have signed an anti-war petition that was circulated for four months in the Soviet Union and then forwarded from Moscow to NATO headquarters in Brussels.

While Soviet authorities arrested seven West European peace demonstrators in Red Square in April, they have also invited other groups of West European peace demonstrators to Moscow as long as their aims and placards have prior approval of the Soviet government. A group of Norwegian anti-war demonstrators accepted such an invitation in spite of considerable criticism of their being compromised by cooperation with the authorities.

The compromises, however, may come from both directions, since the Soviet Union itself gives signs of being infected by the pacifist movement that officials had hoped to confine and encourage only abroad. A Soviet research journal reported that a mere 58 percent of the draft-age sample had positive feelings about doing their obligatory national military service. The famous 1960s peace sign that looks like the bottom of a music stand is making an appearance as graffiti in Moscow and, perhaps most significantly, official publications have begun to rail against the pacifism creeping into Soviet youth.

Soviet chief-of-staff Marshal Nikolai Ogarkov wrote a pamphlet entitled “Always Ready to Defend the Fatherland,” a diatribe against the youngsters who believe, “somewhat simplistically [that] any kind of peace is good, any kind of war is bad.” Published in an edition of 100,000, the pamphlet has a surprisingly similar ring to the criticism of youth made on the other side of the world, where leaders echo Marshal Ogarkov’s view of Soviet youth that “peace is for them the normal state of society. Some of them think that continuing and strengthening it does not require any personal efforts from them. For this reason they sometimes are not aware of and underestimate the danger of war, which has not ceased to be a harsh reality.”

Though the marshal’s pamphlet seems to represent unmistakable alarm among the Soviet leaders about the country’s growing pacifism, it has also been interpreted as an attack not on Soviet youth but rather on those leaders who are considered the doves in the Soviet hierarchy.

Certainly, the slogan “Swords into ploughshares,” which the Soviets espouse at least artistically in their donation to the United Nations, eloquently describes the economic dilemma of the country. Even if the peace movement has not filtered down into society, it must be voiced by some part of the leadership concerned with the mounting failures of the non-military economy. The cynicism of encouraging a West European peace movement while suppressing one in Eastern Europe cannot hide the urgent need of Soviet society to satisfy its domestic consumers. In a part of the world where public demonstrations can rarely be mounted outside official sanction, the idea of a peace movement, ultimately, means a lot less than the sheer pressure to halt an economic deterioration that can be traced directly to military spending.

©1982 Frank Lipsius

Frank Lipsius, feature writer on leave from the Financial Times of London, is studying the neutralization of Europe.