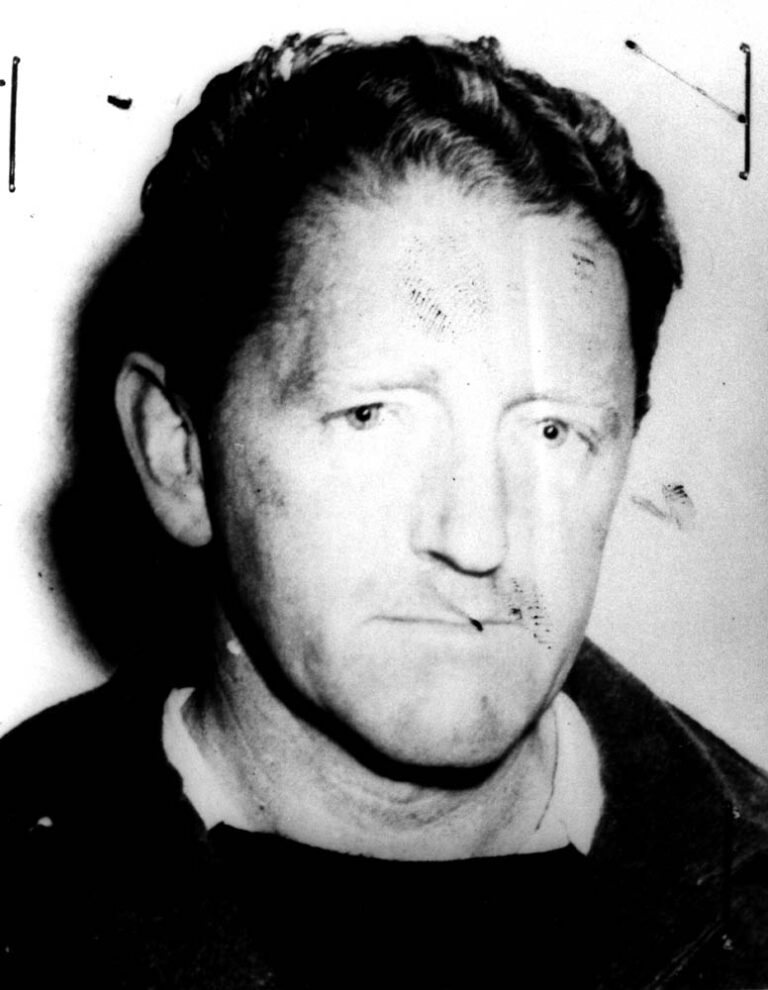

We had just finished our first cup of tea, when Hilda Bernstein rose and left the kitchen. Several minutes passed. Hilda was eighty-one years old and had acquired an artificial hip not long ago, and she negotiated the staircase of the small townhouse outside Oxford, England, with wisdom rather than haste. She came back with a white manila envelope whose contents she dumped onto the table. Out came strips of white fabric, cut in the shape of shirt collars, each one covered in minute handwriting. They contained letters – messages from underground, really – written in 1963 by her husband Rusty, smuggled out to Hilda in dirty laundry from an isolation cell deep in the bowels of Pretoria Local prison in South Africa. Rusty had spent eighty-eight days in solitary confinement there before being charged with sabotage and put on trial for his life alongside Nelson Mandela and nine other anti-apartheid activists.

Rusty sat silently in a nearby chair. He was a quiet man, not unfriendly, not unhumorous, but not inclined to speak until spoken to. His brown eyes twinkled, but his emotions seemed as lukewarm as the tea he was nursing. The letters on the shirt collars seemed to come from a different person altogether – a man in the grip of raw despair and on the edge of sanity, agonizing about his wife and children and his own precarious fate. Hilda and I took turns reading a few aloud. In those moments we were transported back thirty-five years to a prison cell and a country in the process of becoming a police state, and to a family caught in a web in which their political and personal lives were irrevocably entangled.

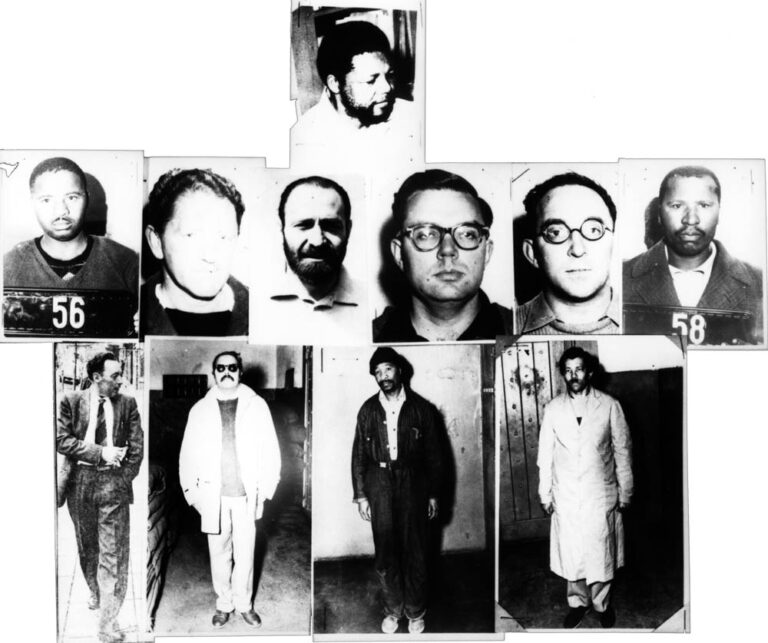

Hilda and Rusty were white, left-wing activists who had worked closely with Mandela and his comrades at the heart of the anti-apartheid movement for more than two decades. They had led double lives, working as middle-class professionals, living in the comfortable white suburbs and raising a family of four children, while at the same time doing illegal underground political work under increasing restrictions and police surveillance.

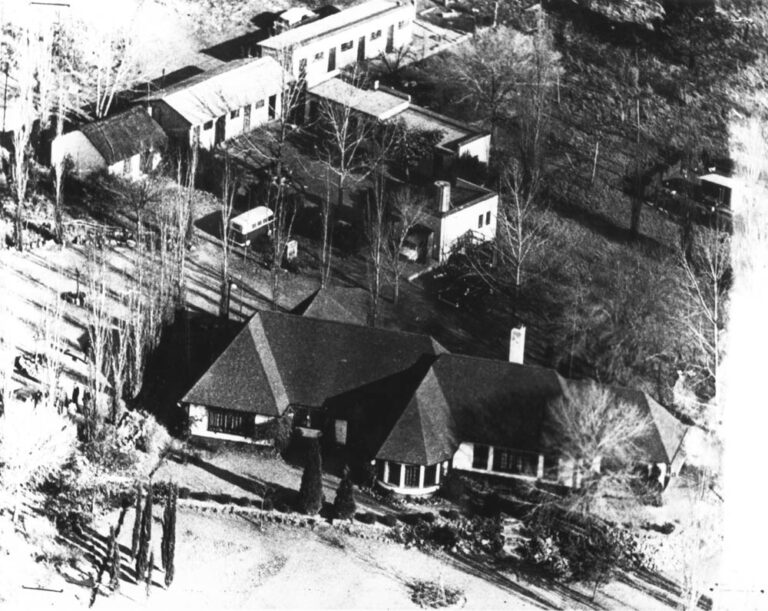

They were integral members of the group that set up a secret headquarters in Rivonia, north of Johannesburg, in 1961 at a time when the movement, frustrated by the inability of its nonviolent protest campaigns to compel the country’s white rulers to the negotiating table, turned to armed resistance. When the regime raided Rivonia in 1963 and crushed the movement, it destroyed the world that they knew. They escaped with their lives, while others were killed or jailed for life. The cause they believed in and struggled for was set back a generation. It took nearly three decades of defiance, unrest and violence for Mandela to emerge from prison and four more years for a new, democratic South Africa to be born. It was a long wait for redemption and many of their comrades did not live to see it.

In the mid 1960s shortly after they set up house in exile in London, Hilda wrote a book called “The World That Was Ours” about the trial. It was published in London and republished in 1989 in a small edition distributed only in the United Kingdom. I came across a copy at Foyles, the London bookstore. The book was a revelation. It was full of passion and anxiety and wonderful scenes and anecdotes, the personal and political powerfully blended. It deserved a larger audience than it was destined to find on a remote shelf in a small back room at Foyles.

Over the years I have come across other first-person accounts from the same period. There was “117 Days,” Ruth First’s story of her confinement and interrogation, first published in London in 1965; “A Healthy Grave,” lawyer James Kantor’s 1967 memoir; “The Long Way Home,” by Kantor’s sister, AnnMarie Wolpe, which detailed her husband Harold’s prison escape; and “A Rivonia Story,” Joel Joffe’s record of the trial, which he first wrote in 1965. Each of these books weaves together in moving ways the history of the era and the personal ordeals and dilemmas of the participants. Together, they constitute an historical record not only of South Africa’s almost forgotten recent past but of the struggle of individuals against state tyranny.

In the end, these white activists — most of them communists and Jews — made a distinct contribution to the birth of the new South Affica. Nelson Mandela has frequently cited their participation in the anti-apartheid movement as justification for the spirit of reconciliation he preaches. The fact that even a small group of whites was willing to put aside their privileged status and fight alongside blacks for racial justice meant to Mandela that people could not be judged solely by their skin color and that all whites should be given the chance to participate in the new society. In a real sense, Hilda, Rusty and their comrades bear responsibility for the surprising degree of racial harmony in the new South Affica.

Of course, Rusty knew nothing of this sitting in his isolation cell in 1963. What he knew was that the movement he had devoted his life to had been dealt a mortal blow. He also knew that his wife, who had been just as involved in illegal activities as he, could be arrested at any time.

Rusty and his comrades were held under a new law that allowed the authorities to lock up anyone who might have information about an offense indefinitely without charge or trial until that person answered questions to the satisfaction of police. Unpublished regulations stipulated that detainees could be held in total isolation without books, pen or paper. Detainees spent 23 out of 24 hours of each day in their cells, with 30 minutes exercise in the morning and again in the afternoon. The only break came when police came to interrogate. It was a regimen designed to break the sturdiest of prisoners, and it would succeed with stunning regularity in the years to come, turning comrade against comrade and supplying police with the information to crush the movement.

Still, Hilda was certain that Rusty would find a way of communicating with her. The families of detainees were allowed to deliver food and laundry once a week to the prison. Every week Hilda examined a piece of Rusty’s dirty laundry, feeling along the seams and lifting each item to the window. She noticed that the collar of one shirt had a corner through which light came. She laid it on the counter, gently ripped the stitches with a needle and pulled out the placking from inside. There, on strips of a torn handkerchief that had been laid flat to match the collar shape, was a message in meticulously tiny handwriting.

I am finding the nights worse than the days. Lights go out at eight p.m. I try to find exercises to keep me up til eight-thirty. But then I wake too early and from dawn to five-thirty is spent turning and tossing and having fearful nightmares…I recount to myself memories of childhood, not in full, but try and discover what makes a nice Jewish boy twice face trial for treason in the matter of seven years.

The first notes were in pencil. Then Hilda thought to smuggle in ballpoint pen refills by shoving them into bananas. Rusty hated bananas — just the smell of them made him gag — and he knew to look inside them. She also shopped for fresh handkerchiefs and shirts with the widest possible collars. The notes provided Hilda with a detailed look at life inside Pretoria Local. They also charted the slow deterioration of Rusty’s spirit.

The thought of being in prison for a long time is awful, but tolerable for a man like me. The discomforts and privations mean very little to me. The worst of it is the separation ftom you and the kids and knowing that all the time I am here they are growing out of childhood, the years in which I love them best, and I can never recapture that…

Rusty was losing control. His hands began to shake. The warder had given him a roll of toilet paper and warned, “You won’t get another one for 30 days.” Desperate for anything to occupy his time, Rusty found himself constantly unrolling and rolling the paper and counting the perforated sections to see how much he had left. You’re going bloody mad, he told himself, what are you doing this for? But a day or two later he would be back at it again, counting the sections as if his life depended upon it. I

I feel as though here I am down amongst the dead —- the walking dead. But really my main feeling here is a vast love for you and the children which is slowly breaking my heart, because involved in it is tremendous sorrow for the awful mess I have made of all your lives. There should be heroic and noble thoughts in a time like this to sustain me, but there are not. Just a great pitying for the utter mess I have made at life…

Each week, as required by law, a magistrate with a notebook made the rounds of Pretoria Local asking, “Any complaints?”

One week Rusty replied, “Yes. I want to know what happened about the complaints I made to you last week.”

The magistrate started to write in his notebook. Reading upside down, Rusty saw he was writing, “I want to know what happened about the complaints I made to you last week.”

When the magistrate finished writing, he looked up. “Anything else?”

“Don’t I get an answer to that question?”

The magistrate wrote, “Don’t I get an answer to that question?”

It is hell, not just the loneliness and solitude of tedium but the devilish neurotic fears, anxieties and tensions with only one’s mind for company and nothing to move it to think except one’s own troubles. You can’t imagine what this does to you. You become not just the center, but the whole of your universe, your own fate, your own future. Nothing you can do or say can possibly affect the life of anyone else, or so it seems. What little courage I have gradually erodes in loneliness with no one near to sustain me.

One thing Rusty had in endless supply was time. For years he had been part of a collective movement where his personal needs had been secondary to the historic cause he served. This had suited his personality and his idealism. But deep in the bowels of Pretoria Local, there was no cause and no community to support him. He could see that prison was crushing his spirit. And he could see clearly the price that his family was paying. Thinking about it was sheer torture. He paced the cell endlessly like a hamster in a wheel seeking to drive away his own thoughts. He knew if he began to succumb to self-pity he would be lost forever.

I now really worry about what will happen to me if I am not charged by the ninetieth day, but put back in here for another stay…I don’t know how long I will survive it without being reduced to complete jelly.

On the 88th day of his detention Rusty Bernstein was taken to a prison reception room. A police lieutenant entered, put his hand on Rusty’s shoulder and said, “I hereby release you from detention.” He lifted his hand, took a breath and put it back on the shoulder. “Lionel Bernstein, I arrest you on a charge of sabotage. You will appear in court tomorrow.” That same day, ten others, including Nelson Mandela, were similarly charged. The maximum penalty, for those convicted, was death by hanging.

Rusty’s isolation was over. But his legal ordeal had just begun.

©1998 Glenn Frankel

Glenn Frankel, editor of the Washington Post magazine, examined South African activism during his Patterson fellowship.