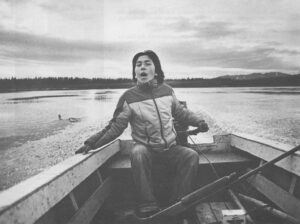

SHUNGNAK, ALASKA – George White molds the lives of thousands of people. Millions of dollars flow across his desk. Mention of his name is sure to draw opinion, while his own opinions are sought by many. A public servant, his salary exceeds the governor’s or the U.S. Senators’. He is one of the most powerful men in this part of Alaska. His business is not oil. His business is children, Eskimo children.

George White is superintendent of Northwest Arctic School District headquartered in Kotzebue, Alaska, serving 1,550 students in grades K-12 with 130 teachers and 227 aides, cooks, custodians, principals and administrators in 11 small villages scattered across 36,000 square miles of roadless Alaskan wilderness. It is an unusual operation. It spends over $6,000 annually per student, three times the national average of $1,800. It pays first year teachers $20,033 for a nine-month contract, half again the U.S. average for all teachers (but less than some rural Alaskan districts). In Shungnak Alaska, a village of 200, it built a $2.7 million school for 75 students. Similar schools are under construction or complete in almost all eleven villages. Northwest Arctic attracts state and federal grants for many purposes, especially those grants targeted for Native Americans, in which the district abounds. Yet with all these resources, the district loses 30 to 40 percent of its teachers every year. And this year, one-third of the Shungnak High School students left their new school (with their parents’ blessings) to go to Mt. Edgecumbe boarding school 1,000 miles away near Sitka, Alaska.

George White is superintendent of Northwest Arctic School District headquartered in Kotzebue, Alaska, serving 1,550 students in grades K-12 with 130 teachers and 227 aides, cooks, custodians, principals and administrators in 11 small villages scattered across 36,000 square miles of roadless Alaskan wilderness. It is an unusual operation. It spends over $6,000 annually per student, three times the national average of $1,800. It pays first year teachers $20,033 for a nine-month contract, half again the U.S. average for all teachers (but less than some rural Alaskan districts). In Shungnak Alaska, a village of 200, it built a $2.7 million school for 75 students. Similar schools are under construction or complete in almost all eleven villages. Northwest Arctic attracts state and federal grants for many purposes, especially those grants targeted for Native Americans, in which the district abounds. Yet with all these resources, the district loses 30 to 40 percent of its teachers every year. And this year, one-third of the Shungnak High School students left their new school (with their parents’ blessings) to go to Mt. Edgecumbe boarding school 1,000 miles away near Sitka, Alaska.

The education of Alaska Natives was once a low budget, low priority, almost forgotten affair. Now education is the biggest state government operation in terms of dollars, $352 million this year. It is on education, in fact, that much of Alaska’s oil-related wealth is spent. Accordingly, the activities of rural high schools increasingly are debated all over Alaska. Are the new schools working? Are we spending too much?

One hundred years ago, this region of Alaska was uncharted wilderness. The first sizable settlement of Kobuk River people wasn’t visited by westerners until 1883, although coastal Eskimos had been trading with whalers for some time before that. The people were seminomadic, living in large winter villages, then scattering in summer across the land to hunt, and along the river to fish. The first school in the Shungnak region was established by the Friends Church 75 years ago. Later the Bureau of Indian Affairs opened schools and the settlement process began.

“My parents stay up river year round sometimes,” Shungnak elder Wilson Tickett remembers. “Good hunting ground up there, trapping. That’s why they never come down here. Good wood up there, too. Sometimes my parents sent me down to stay with somebody to go to school, three months, sometimes, in winter.

“Until my kids were old enough to go to school, we stayed year round at Mauneluk (River) mouth. We moved down here when Michael was eight years old.” Wilson now has grandchildren in school. His family has long since settled in the village, as have his childrens’ families. Multiply the process of settlement by 20 or so families, and the village was born.

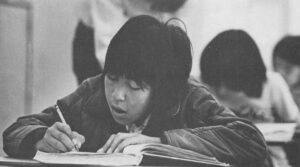

Yet the school was never of the village. It was created by outsiders, controlled by outsiders and staffed by outsiders. It is a settlement pattern distinctly different from the rest of the country, where schools were locally conceived, financed and controlled. “Sometimes teachers stay one year, two years, three or four years. Some teachers, they never stay very long. I don’t know why. Some teachers, they don’t want to go away. But their time is up,” Wilson remembers. The Bureau of Indian Affairs regularly rotated its teachers, discouraging community participation. “When we were in school, we divided into two groups. When somebody talk Eskimo in the other group, we have to mark them. They have to stay after school, write about 25 times, 50 times, 75 times, 100 times, ‘I will not talk Eskimo in school. I will not talk Eskimo in school….’” The schools’ mission was acculturation, which in most instances meant the imposition of western culture on Eskimo civilization. Students who wanted to continue their education beyond the eighth grade were sent to boarding schools with other Native students.

By the seventies, Native leaders were dissatisfied. Students who went outside to school often had trouble readjusting to village life. They missed growing through their adolescent years surrounded by family and never learned vital subsistence skills. Students who chose to stay at home forfeited their chances for higher education. There had to be a better way.

In 1972, a Yupik girl from Emmonak, Alaska, joined in a class action suit against the state, alleging it was not providing her with an adequate secondary education. In 1976, the state signed a consent decree, agreeing to provide high schools in any of 126 villages that requested them. Twenty-one Rural Educational Attendance Areas were created, of which Northwest Arctic was one. It attracted as superintendent the former head of all state operated schools, George White.

As it turns out, the challenges of creating and running those bush high schools have been terrific. Typical villages of several hundred people are reachable only by bush plane. Everything is frightfully expensive, from fuel oil to mimeo paper. The Eskimo culture – hunting and trapping and fishing and gathering – is very much alive here. Many young people plan to live in the village the rest of their lives. Should they learn algebra or dog sled building in the tenth grade? Can five teachers handle the entire curriculum from seventh grade to twelfth? Are they offering enough depth and diversity to prepare students for college? Questions like these brought educator Ray Barnhardt to nine different villages to study bush high schools. Barnhardt, director of the Center for Cross Cultural Studies at the University of Alaska in Fairbanks, recently released the results of his study in a widely quoted report. “We became concerned with the attention given to the tangible facilities (buildings), while very little concern was given to the programs in those facilities. What was happening was that they were taking the high school model from down here and transporting it to the village,” he said later.

As it turns out, the challenges of creating and running those bush high schools have been terrific. Typical villages of several hundred people are reachable only by bush plane. Everything is frightfully expensive, from fuel oil to mimeo paper. The Eskimo culture – hunting and trapping and fishing and gathering – is very much alive here. Many young people plan to live in the village the rest of their lives. Should they learn algebra or dog sled building in the tenth grade? Can five teachers handle the entire curriculum from seventh grade to twelfth? Are they offering enough depth and diversity to prepare students for college? Questions like these brought educator Ray Barnhardt to nine different villages to study bush high schools. Barnhardt, director of the Center for Cross Cultural Studies at the University of Alaska in Fairbanks, recently released the results of his study in a widely quoted report. “We became concerned with the attention given to the tangible facilities (buildings), while very little concern was given to the programs in those facilities. What was happening was that they were taking the high school model from down here and transporting it to the village,” he said later.

The report concluded: “Many small high schools are doomed to failure, along with a generation of young people whose education will be sorely needed during the next decade…Small high schools can be developed into effective institutions, but not without a careful rethinking of their basic functions and design…”

Barnhardt’s key concern, he related in an interview, was the continuing lack of local involvement and control. “We identified Northwest Arctic School District as one of the few districts trying to do something. Most districts weren’t doing anything.” The praise was for involving communities in curriculum planning. “We need to get local people into the system as administrators, teachers. Until we do that, all these other things will have a basic limitation to them. Decisions are made by people who have only distant perceptions of the village. There is a shortage of teachers for rural schools, especially for Alaska trained teachers. Eighty-five percent of all teachers in the state are issued a certificate based on training outside of Alaska. One percent are Native Alaskans. Most of the people are transients. They don’t develop sophisticated, well-run programs. Inevitably, you have to start over every year. Things never grow; they go in perpetual circles.”

Northwest Arctic is a good example. Its 130 certified teachers include only two Eskimos. Most of the district’s teachers are transients; 30 to 40 percent leave their villages despite high salaries.

“It’s the teachers who have to be stabilized,” said Guy Stringham, the new principal of Shungnak school and a longtime Alaskan. “Teachers from the lower 48 can’t survive in this environment. We’re foolish if we think they can. By and large, 99 percent of the people who come up here aren’t going to make the adjustment.” Village life is untenable to many. The climate is extreme, with temperatures as low as 50° below zero. Teacher housing can consist of one room, a wood stove, no running water, an electric hot plate and an outhouse out back. Teachers accustomed to a cosmopolitan university town find themselves in a totally isolated village and a vastly different culture.

“We are unique,” Stringham says of Shungnak’s staff. The teachers live in Native housing, mostly log cabins, and enjoy it. One is married to an Eskimo. Half the staff returned last year and all expect to stay next year. They are liked and respected by the village. It is an unusual and positive situation. Northwest Arctic assigned one of its most promising principals to the school and agreed to offer two half-time contracts to a husband-wife team to encourage them to stay.

How else does the district encourage teachers to stay? Primarily with generous salaries and benefits (which at Alaska prices don’t go as far as one expects). First-year teachers complain they are hired not knowing what rigors await them. Others feel the district ignores them once they are in the villages. George White usually visits Shungnak only once a year, for an afternoon. And a few teachers find the district actively discouraging them from remaining in their village.

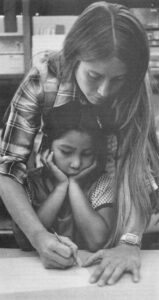

Peter McManus has lived on the upper Kobuk River for seven years, first in Shungnak and now in Ambler, where he built a house and is raising his family. He has developed a free-form teaching style he feels is suited to the Eskimo culture. “The learning pattern of the Eskimo kid is not the same as the white kid,” McManus said. “The Eskimo parent never asks a kid what he learned at school today. It isn’t a question and answer session. The learning is watching. He observes and then goes and does it.” One time, McManus asked an Eskimo elder to come teach sled building. The elder came and simply set about building a sled. “He didn’t get excited about the kid over there drilling holes in the saw horse,” McManus recalls. “But the kid who is ready to tie stanchions gets some pointers. When they’re ready to learn, they’ll learn. He was teaching them in the only way he knew.” McManus learned from the elder’s example.

Peter McManus has lived on the upper Kobuk River for seven years, first in Shungnak and now in Ambler, where he built a house and is raising his family. He has developed a free-form teaching style he feels is suited to the Eskimo culture. “The learning pattern of the Eskimo kid is not the same as the white kid,” McManus said. “The Eskimo parent never asks a kid what he learned at school today. It isn’t a question and answer session. The learning is watching. He observes and then goes and does it.” One time, McManus asked an Eskimo elder to come teach sled building. The elder came and simply set about building a sled. “He didn’t get excited about the kid over there drilling holes in the saw horse,” McManus recalls. “But the kid who is ready to tie stanchions gets some pointers. When they’re ready to learn, they’ll learn. He was teaching them in the only way he knew.” McManus learned from the elder’s example.

Last year, a new principal came to Ambler, straight from the lower 48. He was Floyd Ellis, a veteran small school administrator. Seventeen days later, the math/science teacher resigned. By February, two first-year teachers had been “non-retained” which is a nice way of saying, “You’re fired.” And Ellis, who couldn’t fire tenured McManus without cause, recommended he be transferred to another village in the district. Ellis declined comment, saying, “I have to handle these affairs privately.” One of the non-retained teachers claimed Ellis threatened to black ball him if he didn’t resign. “That was strictly in confidence,” Ellis responded. “I was trying to get him to see the light.”

McManus fought the district over the transfer. A professional arbitrator from Anchorage heard both sides and decided McManus would return to Ambler this year. “What really saved me,” McManus said, “was the letter Ellis wrote to me, telling me I wasn’t respectful. Defending other teachers was how I could get into trouble.”

George White declined comment, saying, “We could get sued.”

But personnel director John L. Rogers explained, “Pete had been in Ambler for a number of years and was getting involved in local activities. Being in a village for an extended amount of time, teaching abilities show a decline. We felt it was time for a change. In the principal’s opinion, Pete was not performing in the class room as he thought he should and as he expected he should.”

Ray Barnhardt commented, “When someone gets too chummy with the community, they get transferred. A favorite tactic is to move them into central office,” which is what Northwest Arctic did in this case, except it was Ellis who got transferred. The disturbing thing for McManus and other teachers is that a newcomer like Ellis who understands nothing about Eskimo culture can disrupt staff and community overnight.

“I have great power,” Shungnak principal Guy Stringharn said. “I can make or break programs,” which is exactly what he was doing after three months in the village and a few local school board meetings. Faced with declining enrollment, he closed a school operated community cafe. The cafe was the brainchild of last year’s principal and home economics teacher, both of whom left. Serving hamburgers, ice cream, baked goods and soft drinks, the cafe attracted crowds of villagers when it opened after school. The sponsoring teacher donated innumerable hours to keep the operation going. His students were learning to make change quickly, work as a team, keep things clean and take orders. When Stringham discovered that a temporary health permit had expired, he closed the cafe. Then he delayed applying for a permanent permit, while the community heard promises of “next week,” or “next month.” The permit never was applied for and the cafe died. Thirteen thousand dollars in brand new equipment – ice cream maker, refrigerator, deep fat fryers and freezer – all sit idle. The sponsoring teacher is frustrated, but resigned to the situation.

“After we get the cafe built, what then?” Stringham asked. “How many kids can actually work in a cafe in Shungnak (which has no cafes). The question is, can you do more by putting kids into other skills, carpentry, metal work, lapidary…” Whether he was wrong to close the cafe or the former staff was wrong to open one isn’t the point. “Year after year,” Stringham said, “a new person comes in and changes the whole impact, the whole program, the whole world.” Stringham, even seeing the problem, feels he has to reorder the program to his own priorities. He’s planning to stay for three, perhaps five years. What then?

The cafe isn’t the only example. Shungnak school owns a complete set of grow lights for a hydroponic greenhouse. After the maintenance supervisor pointed out it cost $300 a month to light a couple dozen tomatoes, the greenhouse was scrapped. Apparently a potter passed through one time, for there are two electric potter’s wheels and a large electric kiln in storage. The new shop teacher found a perfectly good table saw in a jumble in a storage shed and restored it to service, shaking his head in wonder.

If continuity of staff and program is a goal of Northwest Arctic School District, it isn’t always evident. Noorvik School had seven principals last year, one of whom lasted one day. “Since the district began three and a half years ago,” White said, “Certainly we’ve had problems. Before that, there was no continuity of program. Curriculum guidelines for the district have been developed. You have to have program continuity. Without it, you don’t have an educational system.”

There always seems to be money available, though, for new programs if old ones aren’t working out. A University of Alaska professor (not Barnhardt) familiar with Northwest Arctic characterized their philosophy like this: “When you see a problem, throw money at it. If it’s still a problem, throw some more money at it. That’s why we get two color video cassette recorders.”

Perhaps the most disturbing development was the decision by seven Shungnak students to go to Mt. Edgecumbe Boarding school near Sitka. Certainly, some of their motive is the old “grass is greener” phenomenon. They no longer have to go to Edgecumbe, so some want to go. It means a free trip to Sitka and back, new friends, more courses, and new teachers. For college bound students, Mt. Edgecumbe has a record village schools can’t match. Some 80 percent of the graduates of a recent class intended to continue their education.

“I don’t know why they went out,” says Advisory School Board member Levi Cleveland. “Some parents couldn’t handle their kids. So they go ahead and send them down to Edgecumbe. If I were that age, I’d finish high school in the village, then go on to college. Then I’d know more about what was going on in the village.” Other parents think that exposure to what’s going on Outside is equally important. Learning in a larger school can mean more challenges and more opportunities. An undercurrent usually is, however, discipline. Local high schools have introduced an unexpected element of vandalism and violence to the eternally placid Eskimo villages.

“My kids,” says Wilson Tickett, “we sent them out for high school. Right now, kids stay home for high school. That time when we send them out, less trouble. Right now, more trouble. I find out all the villages have trouble right now with kids at home.” The trouble manifests itself as discipline problems, poor attendance, drinking, occasional fights and general rowdiness. In many ways, it is the same all over the country when teenagers test their limits. But Shungnak and other villages never had to deal with teenagers as long as the BIA shipped them out to boarding school. Today’s Eskimo parents are confused about how to discipline an errant teenager.

Native leader John Schaeffer addressed the problem in a meeting in Shungnak this winter. “A lot of our parents feel guilty, ‘It’s our fault.’ Instead of trying to do something about them, we let them go. If somebody comes and says your kids are doing wrong, you say, ‘Get out of here!’ The school district spends $30,000 a year replacing windows in Noorvik. At Noatak a year ago, kids were going around scaring the hell out of people. And they got away with it. In Kivalina, they closed down the school for a few days. The upper Kobuk is being known for its robberies. If you don’t control it someone else will. Anchorage will. Let me tell you how they’ll do it. Anchorage people don’t like all this money going to bush schools.

“I hate to see something like this tearing up the villages. If they don’t learn to respect their elders, it’s going to get worse and worse. Their children won’t respect them, either.”

Lest one get the wrong impression, schools open every morning at nine a.m. in Shungnak and countless other villages. They teach students a variety of subjects, play a lot of basketball, and have dances, like schools everywhere. The school boards meet to debate curriculum and budgets. Some problems can be chalked up to start up difficulties. But that doesn’t make them any less real. “The first year, we spent a lot of time with the communities,” George White said. “Once we started trying to develop all the ideas, we lost contact with the communities…As administrators, we sit in our little chairs and think we have to make a lot of decisions. We don’t.”

Given the vast investment the state has in local high schools they probably will not be abandoned. Whether they will adapt to meet the special needs of the Native communities they serve is far from decided. Surely it will vary from village to village and from year to year.

In Shungnak, the permanency of the current teaching staff is a good sign. Bilingual and bicultural programs are being expanded, recognizing that living in the Arctic requires special skills, certainly a reversal of the old BIA approach. “All the culture should be included,” Levi Cleveland said. “Get those kids to understand all the ways Eskimos used to live, hunting, fishing, survival. It looks like it’s heading that way, but it’s not enough. All these kids don’t know how to cook what we used to eat. I think trapping should be included. Maybe we should take some of those boys along and show them how to set traps – beaver, otter, fox, marten, lynx – they’re all a little different. Especially otter, you got to set them underwater.

“The main thing is to have kids educated. You got so many high school dropouts. It just doesn’t seem right. I don’t know what turns them around – the school and how it’s operated have something to do with it. The parents should pay more time to the school. Then they would have more to say, rather than let the teachers, the principal and the community school board run the whole thing.”

©1980 Jim Magdanz

Jim Magdanz is spending his fellowship year in Shungnak, Alaska reporting on Subsistence Living in a Changing Eskimo Village.v