Louisiana has a spectacular history of corruption, most of it by Democrats. Disgust with that legacy animated Republican leaders, who took party organization as seriously as their rock ribbed conservatism. They had to. Outnumbered 3-to-1 by Democrats, Republicans held few offices until the 1980s, when a succession of Louisiana legislators began switching parties.

By 1988 there were 24 Republicans out of 144 in the two chambers. Three of Louisiana’s six Congressmen were Republican, and Secretary of State Fox McKeithen soon shocked his daddy, former governor John McKeithen, by leaving the Democratic told. In the last four years, seventy lower-level Democratic officials also have become “switchers.” Republican control of the White House was a boon in attracting Southerners at odds with national Democratic policies.

It took more than a generation, from mists of the Eisenhower era, to build Louisiana’s Republican Party and just four years to wreck it. GOP veterans pin much of the blame for today’s disarray on a cadre of evangelical Christians who swept into the State Central Committee in 1988, capturing a third of its 144 seats. Thousands of evangelicals in Louisiana also supported David Duke. Gone from office, Duke is not forgotten.

‘The Louisiana Republican Party is an empty shell,” says University of New Orleans political scientist Charles Hadley. “David Duke pretty much destroyed it. They’ve had no mail solicitation [of money from members] for the last two years. As recently as 1988 they were operating on a $500,000 budget and had to use a secondary facility for computer operations. The evangelicals are quietly going about the business of capturing the party apparatus”-or what’s left of it.

In early 1988 former chairman George Despot wrote a prophetic internal memo, warning that televangelist Pat Robertson’s forces wanted “to take control of the state Republican party.” Beyond support of Robertson, then- overriding issue was abortion. To party loyalists, most of whom already opposed abortion, that obsession meant trouble.

‘The born-agains have several leaders who control their votes,” says John Treen, brother of former Governor Dave Treen. “In the past we didn’t have bloc voting in the State Central Committee. Everybody was an individual, voting their conscience. It was like an open debating society, a good representative body. Trying to reason with these people is like trying to teach calculus to a second-grader.”

Other GOP veterans criticize the “born-agains… support of unsuccessful candidates in races Republicans might have won. But the born-agains are symptomatic of deeper turmoil in a state party fractured by racism, in fights. and feuds with national leaders. Republican National Committee operatives clashed with state chairman William J. Nungesser, 63 over his handling of Duke and former Governor Buddy Roemer’s reelection campaign.

Billy Nungesser’s term as chairman ended in November; he did not run again and most Republicans were relieved. In May, when the vice-chair, Sally Campbell, backed by Cong. Richard Baker of Baton Rouge, tried to oust him, Nungesser’s allies moved files out of party headquarters the night before the vote.

‘The evangelicals wanted to take over the party and the Bush people made deals with them to ditch Nungesser,” said a party source. “When Billy found out, t was the last straw.” Still, Nungesser foiled the challenge and remained chairman until his term ended.

“I was put upon or encouraged to run for chairmanship by Baker and others,” concedes Sally Campbell, a Slidell evangelical and longtime GOP activist. “Billy has a real problem with [RNC] interference and in a lot of ways I think they’ve gotten a black eye in the state. Billy’s a very shrewd politician.”

With wavy red hair, streaked gray, and a raspy voice, seasoned by years of cigarettes, Nungesser has bruised the egos of just about every major player in the state party. “Billy doesn’t have the ability to say no,” claims a friend. He has rankled others with hard candor.

Nungesser’s bullish style is a throwback to good-ole-boy dealmaking of yesteryear, a style quite distinct from backstabbing techniques taught in the late Lee Atwater’s school of dirty tricks. Nungesser is a hard-line conservative, however his salty wit and rough tactics call to mind that exotic Louisiana liberal, the late Earl K Long.

Nungesser was born in New Orleans the day before the 1929 stock market crash. With modest education he went into a seafood processing business, and became prosperous as a caterer to oil operations in the Gulf of Mexico. “I gave ~4,000 to the Goldwater campaign in 1964,” he muses in his business office, gazing at a china cabinet filled with miniature GOP elephants.

In the 1960s he began raising money for Dave Treen’s early campaigns. In 197 9 when Treen made it to the governor’s mansion, Nungesser went with him as a $1-a-year chief of staff. Last spring relations between the two men chafed when Nungesser endorsed Pat Buchanan in the primaries-the only state party chairman to do so, which infuriated the White House. Lobbing that hand-grenade at Bush was Nungesser’s revenge for the plot to oust him as chair man. But it was David Duke that triggered the rupture between Nungesser and the Republican National Committee.

“I worked forty years for this party,” growls Nungesser. “I didn’t need this David Duke crap.”

Neither did Dave Treen, who last fall swallowed his pride and endorsed arch enemy Edwin Edwards in the gubernatorial runoff against Duke, the nominal Republican with a neo-Nazi stamp.

Only once since Reconstruction has a Republican been elected governor here: in 1979, when Treen, a silver-haired Congressman, won a 950(~-vote victory over Democrat Louis Lambert. Lambert should have won but many people thought he made the run-off via vote theft. In Louisiana’s open primary system-conceived by Edwin Edwards-all candidates run regardless of party affiliation, after which the top two square off. Lambert made the runoff when 14 voting machines mysteriously registered shifts in his favor after polls closed. The man he dislodged, Lt. Gov. Jimmy Fitzinorris, was incensed. So were the other defeated Democrats.They cut bait on Lambert and to a man backed Treen.

Lambert did have the support of outgoing Governor Edwards, who was ineligible for a third consecutive term. Yet even Edwards, who was then highly popular, couldn’t help Louie Lambert un-peel the snakeskin image of those voting machines.

As governor, Treen gave key state jobs to the Democrats he defeated like Paul Hardy, who joined the GOP. A flow of rank-and-file Democrats-a dozen or so “switchers” a month-have since turned Republican. Ronald Reagan’s popularity was a big factor. But Louisiana had a strong negative impetus: Edwin Edwards, who returned in 1983 and defeated Treen in a landslide.

Edwards personified everything that good government conservatives considered dirty about the bayou state. He pushed through a $700 million tax increase in 1984. His extra-marital romps were so well known that he told The Washington Post he was safe with voters “unless caught in bed with a dead woman or a live boy.” In 1986 he was twice tried for racketeering; though acquitted, he lost control of the legislature. In testimony he had admitted handing over $700,000 in suitcases to cover his Las Vegas gambling losses when a casino emissary came calling at the mansion.

In his 1987 reelection bid, Louisiana sank into deep recession as oil prices collapsed. Edwards’ call for a lottery and casino to spur growth was too much for the public to stomach, and he lost to Buddy Roemer, an upstate Congressman. Paul Hardy was elected the state’s first GOP lieutenant governor.

So it was, in March 1988, when the State Central Committee met to select a chairman. Years of dogged organizational work were bearing fruit. Edwards was out. Republicans had the lieutenant governor, more legislators than ever before, continuing “switchers,” and Bush was on a roll.

The State Central Committee members were elected from legislative districts in the 1988 Super Tuesday primary. Pat Robertson was campaigning for president with a network of evangelical ministers, like Rev. Billy McCormack who lives, outside of Shreveport. At the committee meeting to choose a chairman, the born-agains, many of them new to politics, backed David Thibodeaux of Lafayette, a young professor of English at University of Southwestern Louisiana, and a recent switcher. A political novice, Thibodeaux wanted the party chair as a platform to run for Congress. But a Nungesser ally learned that Thibodeaux and his wife were in the midst of a divorce. They had two children. Horrified born-agains dropped Thibodeaux like ;I hot potato. Nungesser was elected chairman.

The born-agains also wanted caucuses to select uncommitted delegates to the national convention.Tapping church pews, they would use sheer numbers to regain delegates for Robertson, undercutting Bush’s Super Tuesday victory. That self-styled “party-building process” lost by 4 votes at the committee. Afterwards, John Treen confronted evangelical leaders: “That wasn’t party-building. It was party-destroying. You lie about your motives. How can you square that with being a good Christian?”

“God wants Pat Robertson to be President,” he was told.

“Anything we do to bring that about is God’s will.”

“I’m amazed that you have so little faith,” said Treen.

Nungesser gave several committee chairman ships to the born-agains to promote unity. “Billy,” said Treen, “they’ll knife you the first chance they get and try and put in one of their own.”

In February 1989, John Treen faced David Duke in the runoff for a vacant state house seat. Although Duke left the KKK in 1979, his racist views, cynically recast as “equal rights for all,” galvanized media coverage. Democratic officials joined Republican ones in supporting Treen. In the final week he was endorsed by Bush and Reagan-a move Nungesser opposed because “it looked like a gang-up.” Duke’s attacks on welfare, set-asides and affirmative action were issues that few Republicans had stressed in a state where such programs had little impact.

Duke also profited by sloppy journalism. Although the Anti-Defamation League circulated material about his neo-Nazi ties, reporters failed to probe that past and kept calling him “ex-Klansman.”

Two nights before the election on a 30 minute television spot, Duke said that John Treen had an arrest record. Duke volunteers going door-to-door told people that Treen was a child molester. On election eve, Treen received obscene phone calls at home till 3 a.m.

Duke won by 227 votes. National chairman Lee Atwater promptly dubbed him “a charlatan” with no place in the Republican Party.The criticism was ironic from an architect of the GOP Southern strategy. Racism was implicit in Republican denouncements of programs designed to lift blacks. Now, however, when the state party sent out a fund raising appeal, several dozen forms came back, scrawled with angry messages-and no money. “Not until Atwater apologizes,” read one. Another: “Since he is espousing a political philosophy which more closely resembles my own I have contributed my support to Mr. David Duke.” Another: “It was shameful the way LA. Republicans treated DAVID DUKE-A MAN OF THE PEOPLE … A GODSENT [sic].” Yet another bristled: “After what you people did to Duke, stick it in your ear.”

Nungesser was in a bind. Having criticized Duke’s “opportunistic character,” he now refused Atwater’s plea to ostracize him for fear of alienating Duke supporters. Many were Reagan Democrats potential switchers. The news vacuum was also widening. The New Orleans Times-Picayune, deciding Duke had profited from overexposure, opted for a less-is-better approach in covering him. Beth Rickey, A 32-year old moderate on the Central Committee, had researched Duke’s past for Treen and wanted him exposed.

That March, Duke flew to Chicago and spoke to the Populist Party, an amalgam of neo-Nazi and far-right extremists on whose ticket he had run for president the previous fall. Rickey followed him. Before his speech (which Rickey secretly taped), a Chicago Nazi named Art Jones, standing next to Duke, shoved a television reporter and said, “You-are a sleaze-ball.” After the tiff aired on several Louisiana stations, Duke circulated a letter to fellow legislators, defending his speech to an “an anti-tax” group. He denied knowing Jones, whom he called “a kook.” A brief story on the Chicago event was buried in the New Orleans daily.

Rickey gave her eyewitness account of Duke’s speech to Bill Elder of New Orleans’ WWL. T.V. The 15-minute report on his monthly Journal aired Sunday, April 3, at 10 p.m. and included footage of two neo-Nazis in Ohio, imprisoned for trying to blow up a school, whose release Duke had championed in 1982. The rest of the local media ignored the story. But Atwater got a copy of the tape and pressed Nungesser to take action. Meanwhile, Rickey bought Nazi books from Duke’s Metairie office while he was in Baton Rouge. Convinced that she had the goods proving he was a fraud, she asked Nungesser to support a censure of Duke when the central committee met in June. Nungesser told her she would “stir up a hornet’s nest and help Duke by giving him publicity.”

Nungesser was no fan of Duke. He watched him milk the underdog status, raking in cash from unsolicited letters at the legislature. At a chance encounter, Nungesser said: “Duke, where’d you earn the money for that $300 suit?” Duke chuckled.

When the central committee met on June 3, Duke hovered about, trying to charm members. He offered his hand to John Treen, who snapped: “You are a lying, character-assassinating son-of-a -bitch!” Three days later, Rickey showed the Nazi books to reporters at the Capitol during an exhibition of Nazi death camp photographs mounted by the Simon Weisenthal Center at the request of Gov. Roemer and the state humanities endowment. TV news showed a flustered Duke; newspapers made little of it.

That summer Duke met with Rickey, trying to win her over. But he couldn’t keep himself from steering their talks to his disgust for Jews and admiration of Nazi history. He was also letting evangelicals know of his “prolife” convictions.

Nungesser, trying to keep a lid on the party, told the RNC to back off. In August 1989, Lee Atwater told reporters in Washington that he understood the Louisiana party’s position “from a tactical point of view … People down there understand [Duke] is trying to get into a fight. Anyone generating publicity for Duke is in concert with him. Without publicly he just flattens out.” Undaunted, Beth Rickey drafted a censure motion with media consultant Neil Curran, himself an evangelical.

The night before the Sep. 3 central committee meeting, they met with Nungesser and Rev. Billy McCormack in a Baton Rouge hotel. In The Emergence of David Duke, an anthology published by University of North Carolina Press, Rickey writes in her article:

“McCormack … planted himself in the only available chair in the room. Nungesser sat on one of two beds, while Curran and I sat together on the other facing him. Chain-smoking and talking in a voice like Marlon Brando The Godfather, Nungesser browbeat Curran and me for two hours You have no right to do this!”

Rickey argued that an investigation of Duke put the party in line with the national leaders: Atwater had censured him. No he hadn’t, Nungesser insisted. Finally Rickey exploded: “Listen, Billy, yesterday I received a phone call that said if I get up in front of the committee tomorrow and move to censure Duke, the caller will put a bullet in my head.”

McCormack, who had been silent, suddenly said of Duke: “This man is evil. You’ve been carrying this burden by yourself and we need to help you out.” Rickey sensed a new ally. The four cut a deal: Nungesser would recognize Curran, who would read a motion calling for a committee to investigate Duke for a censure debate to be held at the committee’s winter meeting.They shook hands. McCormack then asked that they pray. “It was a strange moment,” notes Rickey. “Nungesser, Curran, McCormack, and I huddled together, holding hands, praying for God’s blessing.”

The next day when Curran read the motion, a Nungesser ally immediately moved to table it-backed by born-agains down the line. The plan died. Duke had Republican legitimacy by default.

Louisiana Republicans use a caucus-and-convention system to choose statewide candidates; losers traditionally pledged support of the nominee. The party gained media exposure with the conventions. In 1990, Senator J. Bennett Johnston’s high-profile opposition to Supreme Court nominee Robert Bork made him a marked man. Fox McKeithen had the best shot. As Secretary of State, he had an electoral base. But another switcher, State Sen. Ben Bagert hit the road, seeking caucus delegates. None of the party veterans thought Bagert could win; but his pro-life stance won evangelical support. Bagert won the nomination. Before the convention a Duke delegate was exposed in press reports for Nazi ties; still, Duke spoke at the convention, causing Treen to walk out.

Running as a Republican, Duke by midsummer was at 26% in the polls, with Bagert at half that. The RNC told Bagert to quit. The While House wanted Dave Treen to run as a viable alternative to Duke. Treen had no burning desire to run but was willing-only if Bagert pulled Out. An embittered Bagert refused~ he was the nominee. But five days before the election, with his campaign broke, he saw himself becoming a spoiler for Duke~ so Bagert withdrew, and endorsed Johnston to halt a second primary. In a year of anti-incumbent fervor, the stop-Duke posturing helped him draw 605,000 votes, or 44% and he loomed as a statewide force.

A Duke explored his options, several GOP legislators approached Gov. Buddy Roemer in early 1991 about switching parties. A conservative reformer, Roemer had an irascible strain that put off many politicians. “But,” says Rep. Quentin Dastugue, “if a sitting governor switched, it would be a coup for the party, especially if we could get him reelected.” Roemer was interested. Dastugue asked Nungesser for assurance I fiat Roemer would face no GOP opponent.

“And I told Dastugue I couldn’t make that guarantee,” says Nungesser. “Polls showed that Roemer could be beaten.” McKeithen. Baker and IA. Gov. Hardy were considering the race. So was former governor Dave Treen, and he more than anyone else worried Roemer. In early 1991, with Roemer on a trip to Washington, a reporter asked Nungesser if a switch was imminent. Nungesser contacted an aide to White House chief of staff John Sunnunu, he said, ‘I had to know’, but they said ‘no truth to the story,'” continued Nungesser. They stonewalled us all the way. They had been dealing with Buddy Roemer from late summer (1990). In December I had to issue the call for a [gubernatorial nominating] convention in the spring.”

“When Roemer decided to switch,” says Dastugue, “he did it with the white House, That’s where the jealousies came about. The White House should have made sure the state party was involved, but there was distrust because of the Duke stuff.”The RNC blundered by failing to convince Cong. Clyde Holloway, whose district was disappearing because of reapportionment, not to run for governor. Holloway, a pro-lifer, was lining up born-again support.

In early March, Roemer’s staff and RNC operatives met party insiders to map plans. Dastugue: “Billy started talking about Holloway staying in the race. It’s like You’re trying to sell someone a product but saying, you still can’t guarantee it’s gonna work. People got perturbed.” Thus Roemer hosted a luncheon, aimed at mollifying potential opponents Dave Treen, Paul Hardy, Fox McKeithen, Richard Baker, and Clyde Holloway-“who tell he wasn’t talked to in the right tone of voice and went away mad,” says Dastugue. Treen promised not to run.

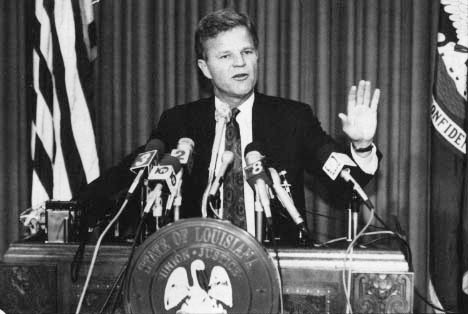

Dastugue, Nungesser and several RNC staffers went to Roemer’s office where the governor brooded about mechanics of [he switch. Nungesser again said that he couldn’t keep Holloway out and Roemer snapped, “Shut tip! I’m tired of hearing about Holloway.” Simmering, the governor known for powerful stump speeches walked into the reception room to greet his new party members. He stood up on a piano stool and read a statement asserting his switch in a voice so dead that people were stunned. “Here we had the first sitting governor-which party wouldn’t want him?” says Dastugue. “Well, we found out. It was the most asinine thing I’ve ever seen in my life. It was a combination of Buddy’s personality, Billy’s personality, and Holloway’s emotions.”

Indeed, at a later meeting, Nungesser and Roemer got into it again when the chairman told the governor he wasn’t showing well in the polls. Roemer said he had always under-polled, and demanded that the convention be canceled. No way, said Nungesser. “F- you, Nungesser!” shouted Roemer. “I want you to cancel that convention!” Nungesser fired back choice expletives of his own.

And so the Republicans fielded not one, but three candidates-Roemer, Holloway, and Duke-which delighted Edwin Edwards, who slashed away at Roemer from the left, while Duke and Holloway attacked the governor from the right. Roemer scaled his fate with the born-agains by vetoing an anti-abortion bill, which the legislature overrode. When Duke knocked Roemer out of the primary, it was a Republican nightmare. Edwin Edwards, the Democrat they hated most, had to save the state from a schemer whose record of Nazi apologetics was now being unearthed in huge scoops each day on the news.

In a cynical pitch for votes, Duke proclaimed himself a born-again Christian. When Neil Curran and several ministers met with Duke, they asked when he had found Jesus. At age 13, he said. How did he explain all those years of cross-burnings, hate literature, celebrating Hitler’s birthday’? “Oh, I backslid,” he said-evangelical parlance for the sinful weakness of all believers. Twenty five years of backsliding? As his campaign floundered Duke attacked Edwards’ religious beliefs, the sure sign of a desperate man. Edwards’ crushed Duke with 61%, of the vote-with bad reverberations for the GOP. A massive black turnout helped defeat Lt. Gov. Paul Hardy. Fox McKeithen barely squeezed by as Secretary of State. And the Republicans, lost three seats in the legislature.

This past June, Gov. Edwards faced his own avalanche of criticism in the Picayune by ramming through a controversial bill for casino gambling in New Orleans, with a state gaining commission whose members he would appoint. He offered the first seat to the LSU chancellor, who declined. He then turned to Billy Nungesser, who accepted it, to the shock of many Republicans.

“I was opposed to casinos,” reflects Nungesser, “but, if it’s gonna happen, I want to see it’s done right. I ain’t gonna be like the guy playin’ piano in a whorehouse who doesn’t know what’s goin’ on in the back room.”

©1993 Jason Berry Jr.

Jason Berry is a freelance writer in New Orleans who is researching the unusual politics of his state.