Text and photos by Jill Freedman

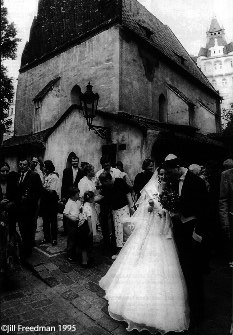

PRAGUE – Rabbi Karol Sidon is the only rabbi in the Czech Republic. His wife, Ruth, is a convert, and so is he, since their mothers were Christian. She didn’t even know of her Jewish grandmother until she was 33 and divorced with two kids of her own. Like most of Czech Jewry, her family was assimilated, so that when her father finally told her, she asked him why he waited so long. Why now? And got the standard reply: “It’s too hard to be a Jew.

The Communists finished the Nazi’s work. It was too hard to be a Jew. Except for a handful here and there, middle and eastern Europe is Judenrein. It feels bad.

Carol’s father, Alexander, was murdered by the Gestapo when he was two years old. He had been in the underground, and was tortured and hanged in the Old Fortress at Theresienstadt. Karol’s mother then hid with the baby in her mother’s village, hiding him the cellar by day, and letting him out at night. He doesn’t remember much of this, he was too young. After the war, she remarried another Jew, Josef, who had survived by his wits and even had escaped from Treblinks. He was one of the very few to escape to the forest and not get killed by the Ukrainians, Polish partisans, or peasants. They might have been fighting Nazis, but they loved killing Jews.

Eighty-five percent of Czech Jewry died during the war. Think, if only there were more acts of mercy (“righteous among the nations”). The numbers would be much lower than 85 percent. How few there were!

So Karol Sidon had known all his life he was Jewish, but he had to formally convert, since under Jewish law the mother must be Jewish. Ruth Sidonova, after discovering her Jewish grandmother and forcing her father to speak of it, felt connected to this religion, something deep inside here, and began studying it on her own, since in the days of the Communists, Jews were verboten.

She met the rabbi through her son, who had done to Jerusalem to study. He introduced them, she began studying with him, and after a year they married. He had four kids, she had two. They decided to consolidate. When she told her mother she was converting, marrying a rabbi, and taking the name Ruth, her mother said, “Jeziz Mariá!” Funny, Ruth said, her mother’s first husband was a German, and now she has a Jewish daughter.

The Funeral

There also is only one cantor in the Czech Republic. The only other cantor, Mr. Bloom, died right before Rosh Hashanah. And so there was no one to sing Kol Nidrei in the Jubilee synagogue, the only time of the year when the main sanctuary is used. The rest of the time, they pray in a small dusty room upstairs, with its peeling walls and old plumbing. They are so few, and it is too sad in that magnificent empty synagogue, with the names of its dead Jews on the stained glass windows.

Mr. Bloom, 82, fell down in the street with a heart attack and was run over by a car. He was the spiritual leader of the Jubilee Synagogue, a man who always had a good word for everyone. The synagogue is barely open. They use it only on the Sabbath, where if they have enough men, ten, to make up a minion, they can pray in that small room off the balcony. But who will sing for them now? Another one gone, a great voice silenced. And now there is only one cantor, Mr. Feuerlicht, left in the entire Czech Republic, to send his voice up to a deaf heaven.

The funeral took place in the Jewish cemetery, called the New Cemetery, since the ancient cemetery in the old Jewish quarter has not been used since 1787. A second old cemetery was consecrated in 1680 as a plague burial ground. After 1787, it represented the main Prague Jewish cemetery. The last burial there was in 1890, except for 180 damaged Torah scrolls which were deported from the Netherlands by the Nazis and buried in 1948.

The present cemetery was founded in 1890. Franz Kafka is there, with his family. There is a memorial tablet for Max Brod, and many other tablets for victims of the Holocaust. There is a monument in memory of the victims of Theresienstadt, erected above a grave with the ashes of 15,000 victims, planted in 1949. The cemetery has many outstanding art-nouveau tombstones, an artist’s delight, and after the Nazi occupation in 1939, the cemetery was the only place Jewish children were allowed to play.

The ceremonial hall of the burial society took ten years to rebuild, and re-opened only two years ago. It, like the rest of “Jewish” Prague, had been allowed to disintegrate and, unlike the proletariat, wither away. Now there is again a place to say prayers for the dead, the last of the survivors. Most of the registered Jews are in their seventies and eighties. When the last of them are gone, there will be none left who remember the splendour of pre-war Jewish Prague, full of its painters, writers and musicians, its scientists and philosophers, its joys and beauties. It will be buried with the last of them.

Graveside, Kaddish, the prayer for the dead, is sung by the cantor, Mr. Feuerlicht, and prayers of farewell by Rabbi Sidon. The widow stands behind them. Danny Sidon, the rabbi’s youngest child, 7, peers down into the grave. The mystery of death: You end up in the cold earth in a wooden box. He is part of the ceremonies, his initiation into the Jewish rituals of death, and then with his stepmother, Ruth Sidon, learns to pour the scoop of earth onto the coffin. Goodbye, Mr. Bloom, may the angels do your singing, for a change. He will be missed.

The Jubilee Synagogue

I went there Friday for Sabbath services and waited outside in the street for someone to come and open it. It looked closed and deserted.

Finally two men came, and I climbed the old stairs to a magnificent synagogue. It’s a big, strong building, with graceful arches and stained glass windows. But it’s dusty and the pews are gone from the balcony. It was so desolate.The praying is done in a little room off the balcony. It needs paint and plaster.

Two young men in their thirties were preparing the sabbath candles and getting things ready. We were alone until a group of students, volunteers in the cemetery and the ones doing their national service, walked in. I knew most, if not all, of these kids weren’t Jewish.

Only three elderly people turned up, and they were tourists. They looked as lost as I felt in the empty synagogue. Where was everyone?

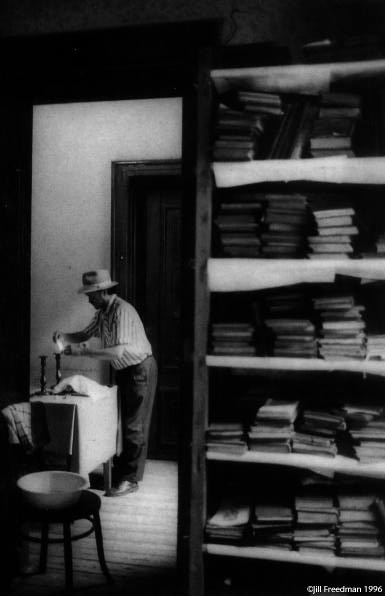

There were piles of boxes filled with prayer books, marked “used books”.

Over the Ark, one bare electric bulb burned, the eternal light.

The main sanctuary is tragic–huge and empty, with the names of its dead, murdered Jews on the beautiful stained glass windows. All those names. They’ve gone and left the place very lonesome.

There are boxes and boxes of books, prayer books, hundreds, thousands, and no one to read them or love them. Gone, all gone.

I sobbed alone, uncontrollably. The names, the loss.

The Kindergarten

One of Ruth Sidon’s projects was to find funding and a place for a Jewish kindergarten, for children three and four years old. She got the funds from the Lauder Foundation, and she found the perfect kindergarten already in existence, which she could join.

This took a lot of time, finding the place, building and furnishing. On opening day of the kindergarten, she was as happy as could be. There was a nice little bathroom with little miniature toilets, little cots for naps, little tables and chairs, and a few toys. Everything was so nice and new and clean and shining, and Ruth was so happy to see her dream realized.

They had a separate kitchen, since they had to observe the laws of kashrut, or keeping kosher. But she still hadn’t found a kosher cook. Only old people in the community knew how to cook kosher, but they were too old to be standing on their feet eight hours a day. She had to find someone they could teach the kosher laws. She still hadn’t found a cleaning person, either.

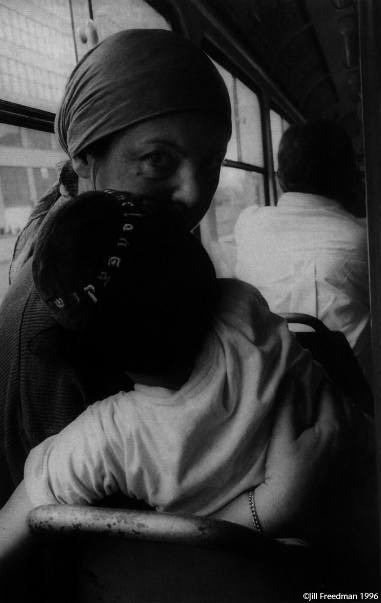

Assimilation is such a problem, she said. Jewish people don’t know the Jewish customs, much less how to keep them. The people who felt Jewish under the Communists emigrated.

The Jewish kindergarten would have its own programs in the mornings, teaching children Hebrew songs and Jewish stories and folklore. They would join with the rest of the kindergarten for the remainder of the day.

It seemed such a hopeful beginning. Slowly they would rebuild Jewish life in Prague again. Very slowly. There were twelve students.

The Old Age Home

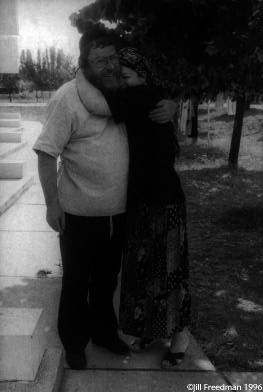

The home for the elderly opened in the fall of 1993. Ruth Sidon goes there often, attending to the needs or just listening to the elderly residents. I was with her when an old lady pointed to the Jewish star she wore around her neck and said, “Nice you can wear the star, I had a daughter in the war, I had to hide the star, bury it in the garden.”

Not that that would have stopped neighbors from tattling. Kill the Jews, save the linen. Of course there were many decent neighbors, but there were too many indecent ones.

Many of these old parties have carefully hidden their Jewishness. It was a dangerous thing to be under the Communists, and hadn’t proven to be a hit with the local populace, either. You can be a ragpicker, they know you have gold hidden in the mattress. So it was easier to be nothing at all. Many didn’t even tell their children about their Jewish ancestry.

It was the same all over Europe.

Of course people were delighted to be able to live openly again. Challah on the Sabbath, a joy.

The old age home is very comfortable. For the first time in more than 60 years here, it’s good to be a Jew. There is a waiting list. And when someone has trouble adjusting to group living (although each has her own flat), Ruth is there to help.

Security is handled by young people serving out their national service. They also spend time with the old people, and run errands for them.

A plaque on wall of the home honors Charles Jordon (1908-1967). He was executive vice-president of the Jewish Joint Distribution Committee and dedicated his life to the service of Jewish communities around the world. He died in 1967 in Prague under tragic circumstances which have never been fully clarified.

This home, built in the years 1992-1993 by the Jewish community of Prague, was named in his honor.

One story is that he had been abducted from in front of his hotel and was found floating in the river. Another theory is that after 1967 war in Israel, there was a hardline Communist crackdown on Jews and Jordan was mistaken for an Israeli agent.

©1995 Jill Freedman

Jill Freedman, a freelance photographer based in Miami, is examining the Holocaust, fifty years later.