In a hot lead operation, any fool could make up a page of straight matter but it takes someone with a certain flair to put together a big display ad. Take one of those supermarket ads. You’ve got maybe six different typefaces in as many sizes. They all have to be leaded right or the page wouldn’t lock. Throw in a bunch of little engravings of pork chops and nylon stockings plus the brand name logos, add a halftone block of a roast turkey and a fancy border around the coupons and you’ve got a hell of a job on your hands. But it’s work that shows what you can do.

So imagine Bill Neelans going out to Idaho a few years back to see the wife’s sister. Neelans is a compositor but has done enough make-up in his day to know its demands. Printers are social sorts who like to drop by local shops in strange places just to see what’s going on. This little paper in Idaho had just gone offset and Bill wanted a look at this new paste-up business. There were all these women bending over light tables, working with itsy bits of paper instead of type. Bill watched a woman put together a big ad. She just took the waxed bits, stuck them down on the page, squared them up and the ad was ready to be shot onto a printing plate. Right then, Bill knew the days of hot lead were numbered. What took a journeyman printer an hour or more could be slapped together by some housewife in a matter of minutes.

Neelans has a very clear-eyed view of the past glories of his trade. He came to LA Type Founders in 1937 along with another young apprentice named Don Winter. There were two owners and the two apprentices. It was the depression and the two apprentices were glad of the chance to learn every machine in the shop. “You figured the more you learned, the better chance you had of holding a job.” The pay was $2 a day. Working a Monday through Saturday week, you could earn $12. “People talk about the good old days but I think about that $2 a day. Hell, the good old days! Coffee was going for a nickel a cup but who had a nickel?”

Even at those rates, two apprentices were more than LA Type could carry then. So Neelans was let go and he went to work for a small job printer until the war. When he came back from the service in 1945, LA Type Founders had grown. There was only one owner and the shop had been organized by the International Typographers Union (ITU). Neelans was hired on with a year’s credit towards his journeyman’s card.

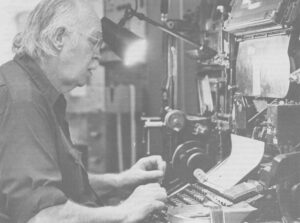

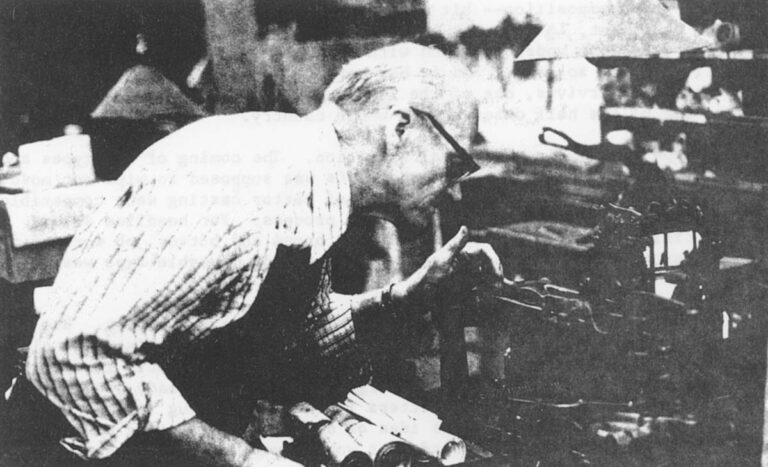

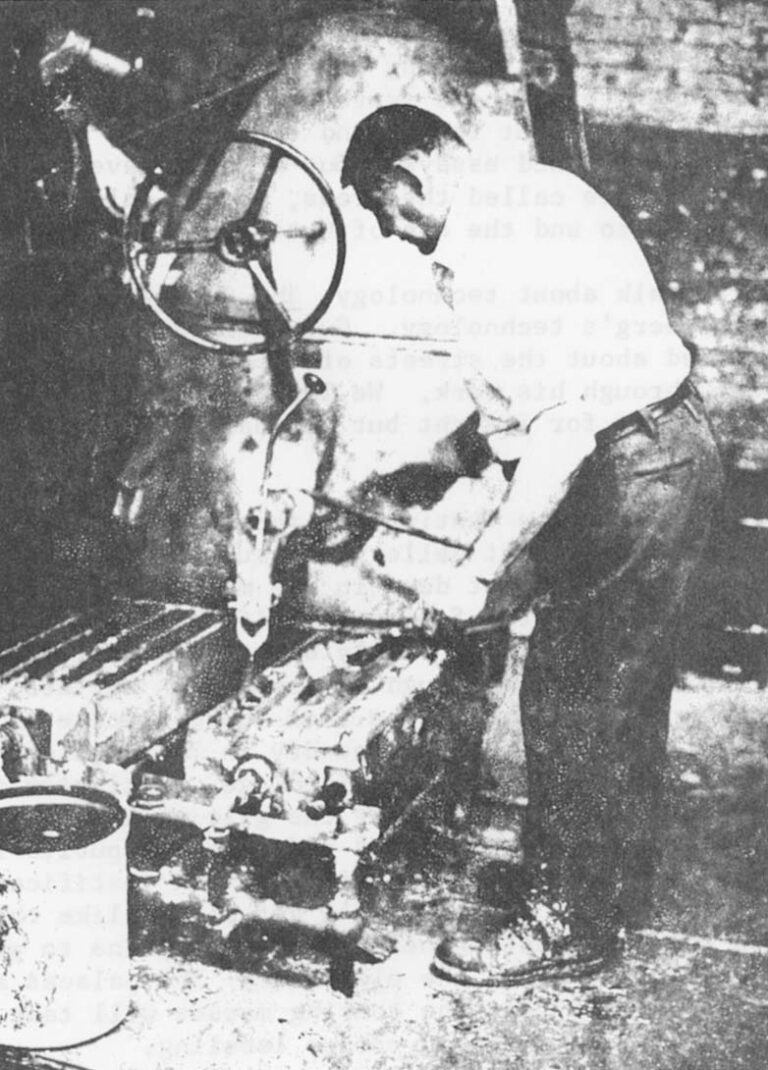

Thirty two years later, he still works the same temperamental type casters, dodging the squirts of molten lead and watching the trade drying up around him. Not that Neelans is immune to the spirit of the age. His son is a mathematician who keeps track of Navy rocket tests in the Mojave desert. Neelans used to work two jobs, putting in eight hours at LA Type and then making pizzas in a franchised parlor. But what with the hours pounding dough and the board of health plaguing him about scratches in the cutting board, he’s put that behind him. Now he’s just hoping that hot lead and LA Type Founders will last him.

Los Angeles Type Founders is on East Pico Boulevard near the center of the light manufacturing district that surrounds downtown. It is the old business district in Los Angeles. The big wholesale fruit and produce markets are just over on San Pedro Street. The garment industry is everywhere; small and medium sized shops that turn out blue jeans and dresses, drawing on the city’s vast pool of minimum wage labor. The district is a magnet for the thousands of “undocumented” aliens who will take on any job as long as the employer isn’t too particular about social security numbers and such. Machine shops, industrial equipment dealers, union halls, specialty manufacturers and, of course, printers attract skilled workers. It’s entrepreneur land. A shop starts up, runs, goes bust. The machines are sold. Someone else moves in, prospers, moves out to better quarters. Other businesses go on, year after year. It’s the mythical marketplace, a sight to bring tears to the eyes of Adam Smith, Don Winter or Milton Friedman tending to the mysteries of a Linotype caster.

On smoggy days, it’s enough to bring tears to any one’s eyes.

From early dawn when the produce trucks arrive till early evening when the garment shops let out, the area is alive with pedestrians, delivery vans, trailer trucks, freight trains, and salesmen. After dark, the streets are empty. Skid row bums wander south at night and The police roust them out of doorways or leave them to pass bottles of sweet wine at bus stops. It is not an important section of town at night.

The other apprentice who joined LA Type Founders in its depression infancy was Don Winter. Hanging on through the early days, Winter saw the company expand, bringing in more journeymen, more Monotype casters and keyboards. After the company moved to East Pico Boulevard in 1941, the type business just got bigger and bigger. Winters remembers that there didn’t seem any way you could miss in typesetting. Although primarily a type foundry, LA Type was pressed into straight composition work during the war, getting all the technical manuals supplied to UUL by Cal Tech to explain the new sophisticated weapons. When Winter came back from his stint in the service, LA Type was getting out of composition to keep up with their main business supplying type fonts to other printers. It was the start of the great printing explosion that has continued to this day. For the next 20 years, LA Type catered to that wild hunger for printing. Then in the ‘60s, a new method of printing–offset lithography tied to computer photo composition–hit the trade. Despite some effort to sell the new equipment, LA Type was left behind with the technology that Winter and Neelans understood and with the machines that LA Type had done so well with for so long. And it has very nearly killed the company. LA Type Founders survives, one of the last two type foundries on the West Coast, one of the half dozen in the whole country.

The other apprentice who joined LA Type Founders in its depression infancy was Don Winter. Hanging on through the early days, Winter saw the company expand, bringing in more journeymen, more Monotype casters and keyboards. After the company moved to East Pico Boulevard in 1941, the type business just got bigger and bigger. Winters remembers that there didn’t seem any way you could miss in typesetting. Although primarily a type foundry, LA Type was pressed into straight composition work during the war, getting all the technical manuals supplied to UUL by Cal Tech to explain the new sophisticated weapons. When Winter came back from his stint in the service, LA Type was getting out of composition to keep up with their main business supplying type fonts to other printers. It was the start of the great printing explosion that has continued to this day. For the next 20 years, LA Type catered to that wild hunger for printing. Then in the ‘60s, a new method of printing–offset lithography tied to computer photo composition–hit the trade. Despite some effort to sell the new equipment, LA Type was left behind with the technology that Winter and Neelans understood and with the machines that LA Type had done so well with for so long. And it has very nearly killed the company. LA Type Founders survives, one of the last two type foundries on the West Coast, one of the half dozen in the whole country.

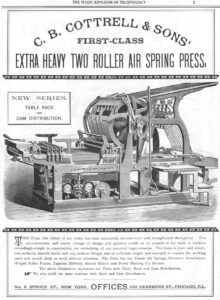

A type foundry is an unusual operation. The coming of linotypes and similar slug casting machines in the 1890s was supposed to wipe out moveable type but it didn’t .Line casting and letter casting were compatible and complementary approaches to the same process. For headline sizes, for specialty advertising types, for the bread and butter job work of the corner printer, hand setting small amounts of moveable type was efficient.

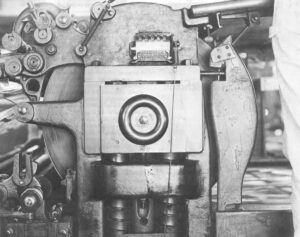

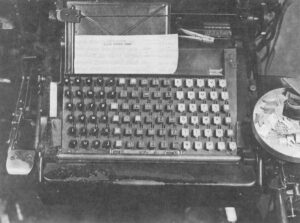

Monotype machines are the peculiar heart of a type foundry. The system was the creation of Tolbert Lanston, an Ohioan working as a clerk in the U.S. Pension Bureau when he took out his first patents in 1887. The inventor of the linotype, Otto Mergenthaler, had already abandoned the idea of casting individual letters in favor of a slug line or “line of type.” Langston hit upon the idea of dividing the setting and casting functions. He devised a keyboard that would punch out paper tape to be run on a separate caster. The tape moved over a pneumatic bar which read the holes and shuttled a casting mat shaped like a square ping pong bat to the right position to receive a squirt of hot lead. Each letter was cast separately and automatically shaved to precision. The machine also cast the spaces needed to “justify,” that is, square off the right hand margin. Monotypes could do straight composition or just cast whole fonts for printers to use in job work. Linotype shops always claimed that their work was sharper than linotype because the casting was more precise. Let newspapers and other “blacksmith shops who just slapped the product together stick to their slug casters, the Monotypers specialized in book and other fine work.

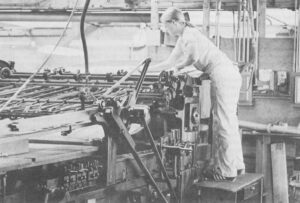

Although LA Type has three Intertype linotypes in the front shop, the heart of their operation is still the long line of linotype casters chugging away. “We’re from the dinosaur age,” Winter says proudly as he takes a visitor through the shop. All the casters are at least 30 years old. In the great collapse of hot lead, LA Type bought up as much of the surplus equipment dirt cheap as they had room to install and work to use it on. Most of their casters were made by the American Lanston Monotype Corporation which has long since gone under. The Monotype Company in England is still supposed to be going strong and Winter proudly shows off an English giant caster that makes the big headline sizes. LA Type got it for a fraction of its original cost. Halfway down the line is a florphan,” an older machine that has been slowly stripped for parts. What they can’t cannibalize, LA Type must patch for themselves.

When the glory years at LA Type ended in the mid-60s, Winter was managing 32 employees, running three shifts around the clock. They were making 100,000 pounds of type a year and turning the stock every year. Now they make about half that and still have a good deal of type on hand years after it was cast. The wrappers tell the story. Winter is standing in the aisles of the stock area. He picks up a package and explains the coding on the wrapper. “We made about 30 fonts of this in 1960 and here we are all these years later and we still have it.” He moves down the shelves reading off dates. May 1962. September 1965.

First it was offset printing and then photo composition,. Art directors who used to order the unusual and exotic faces found they could get even more exotic faces from film setters. One of LA Type’s mainstay accounts was Boeing Aircraft in Seattle. The aerospace slump came on top of the technological shift. Winter had to start letting people go. As a previously stable, union shop, LA Type had held onto its employees year after year. “It’s like a family. There’s gold watches in here by the dozen.” Through layoffs, attrition and retirements, they are down to 10 employees now. Winter is cautiously optimistic. This business has been a struggle but in the last few years, we’re doing better.” Through the late ’60s, photo composition was also killing off competitors like the plague. “That’s all that’s saving us. We’re getting a larger share of a shrinking market.”

The other thing that saved them was a wise investment in molds with Spanish accent marks. While hot lead is succumbing here, it still flourishes outside the technologically advanced countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America. The bulk of LA Type’s sales are to Central America. Certain specialty types of printing such as hot stamping of foils use foundry type. Winter explains that their own type which is still cast from the classic formula of lead with a pinch of antimony and tin is too soft for that kind of use. But the zinc and special steel stamping types are so much more expensive that it pays for small shops to ruin the cheaper lead type and replace it. Schools still teach hand-setting and there are the letterhead and business card printers who will probably use metal type forever. Rubber stamp makers are another group of customers. Final y there are the printing hobbyists who are probably the only growing domestic market but who are a puzzle to a commercial printer like Winter. The hobbyists are unpredictable in what they want to buy. Type founding is a business of keeping up with fashions in type faces. The old best-selling commercial faces are not what the hobbyists want. not a lot of money in casting a whole lot of strange type for a handers fanatic and watching There’s the remainder gather dust on the shelves until the fancy for Gaudy Old Style strikes another hobbyist.

Winter manages the company as a sort of benign regent for the widow of Walter Gebhard, the original owner. Winter keeps his ITU card paid up but is beginning to wonder why. He lost a good deal of money when the ITU Fraternal Pension Fund went bankrupt. In a traditionally nonunion town like Los Angeles, the ITU never got much of a hold in the trade. The troubles of the last years have weakened what they had. Winter keeps his card mostly to avoid trouble but in all the troubles of the past 10 years, union trouble may have to wait its turn in line. Currently, LA Type Founders is working without a contract as the ITU wages a bitter local strike against a handful of target shops. Winter will wait and see.

“Progress” didn’t sneak up on LA type all unnoticed. In the ‘60s they took on three salesmen and signed up as distributors for several photofilm companies but the competition was too cutthroat. Manufacturers came and went overnight. Customers would suddenly switch to newer photocomposition machines, incompatible with the faces that LA Type was selling. One after another, the salesmen moved on and they were not replaced. Gradually LA Type found itself with a simple corporate strategy-survive. The bottom has been reached, Winter feels, and they are still in business. “Eventually there will only be one or two type foundries left in the United States and we hope to be one of them.”

Winter is an amiable survivor who doesn’t take any of it personally. He talks business with a sort of weary realism but when he talks about his machines, his enjoyment sneaks through. Each of the casters has some feature or history bound up in its sometimes recalcitrant operation. Winter points out the splashes of lead on the brick walls and ceiling beams. Everyone in the shop has been burnt by squirts at some time or other. He pulls out a mold to demonstrate how the type is formed. This machine is Japanese and is an almost perfect copy of that machine but at a tenth the cost. Those mats were in those boxes when he joined the company 40 years ago. As far as he can remember, they have never been opened. Type fashions come and go so fast. These mats came with such and such a machine. Didn’t need them. Already had two sets of unused ones but no one else wants them. The “orphan” gets a pat on its dusty levers. The spare parts department.

The future? “Hot lead will die. As these machines and mats wear out there’s no way to replace them. It will die out, maybe not in my life but probably in yours. It’ll be like blacksmiths. There are still some blacksmiths doing good business but there used to be thousands.”

The analogy to blacksmithing is not perfect but it will serve. In the last 15 years in this country, the technology of printing from moveable or cast metal types has been displaced as completely as the horse was ousted from the transportation business by the automobile and the motor truck. The metal printer-linotypists, make-up men, type founders, stereocasters and photo engravers–are fast on their way to joining the blacksmith, the harness maker, the carriage builder and the horse teamster as peripheral or antique occupations. In an industry as large and as complicated as printing, there are many quibbles, qualifications and exceptions but the method that was invented by Gutenberg in the 15th century has in our day been superseded by a new photographic and electronic process. It is a revolution and although the word has been worn smooth in our age, there is no other to describe what has happened.

This is not to say that printing has been rendered obsolete. Print shows every sign of continued growth. Provided the industrial world doesn’t destroy itself (or is not destroyed by others) in the raw materials squeeze, Americans will have even more print coming out of their ears than ever before-books, income tax tables, tickets, magazines, pamphlets, stamps, money, flyers, can labels, frozen food packages, airplane schedules, vinyl floor coverings, multiple choice intelligence tests, fast food hamburger boxes, bank statements, applications, reports, court decisions, fortune cookie fortunes and, of course, foundation newsletters. The generations yet unborn will get theirs.

Yet something has happened, something that goes beyond nostalgia. Those who have written about this overthrow of one technology by another have largely been concerned with the displacement of workers or where the new machines will carry their proud but somewhat nervous owners. These subjects are worth exploring but there is another opportunity dangling before us–a chance to look the beast of technology right in the eye. In polite society, talking about how technical things are done is considered slightly vulgar. Computers and all that are a bore. Let the computers keep track of our charge accounts but leave us in peace. Let technology remain the great cliché, the heir of all the 19th century’s “fond hopes in it progress.” Progress as a civic virtue has been getting a terrible press these days but we all know that progress or technology can’t be resisted. Past ages believed in the inevitability of the Last Judgment. We believe in the inevitability of the computer, what Lewis Mumford called “the myth of the machine itself: the notion that this machine was, by its very nature, absolutely irresistible–and yet, provided one did not oppose it-ultimately beneficent.”

Supposedly our society has split into the two camps of “environmentalists” and “technologists”–a macramé America squared off against a cybernetic one. Yet the most devout home vegetable canner must share Bill Neelans’ epiphany in the paste-up room of that Idaho newspaper. What was once a matter of great skill is made easy by the new technology. Even the most diehard breeder reactor engineer knows that technology is a tiger to ride at some peril. Getting off is not a safe option but the tiger has not made his intentions plain.

“Occupational guidance counselors” can glibly say that we will all have to change occupations two or three times in our working lives. Few of us know firsthand what it is to live inside an accelerating technological revolution. Printers know. Consider also those basic values handed on in hoary adages to youth such as “Find a good trade and stick to it.” Here we have an entire trade going on the rocks and no one is bothering to fish the survivors out to ask them about the limits of old adages.

Finally there is the distinctive role that print has in our culture. Education still sorts out the young largely on their proficiency with printed material. but we don’t want to bother students with the boring details of how that pile of paper is generated and how its production affects its contents.

That brings us to Gutenberg. When writing about printing, the etiquette is to get in a word about Gutenberg at or near the beginning. Gutenberg blends a certain traditional air to the proceedings. No matter if you are writing a high school industrial arts text or dropping a few belles lettres of handset type into a morocco-bound private edition, it shows breeding and a commendable sense of history to lead off with the shadowy German, the father of printing, a genius of the first water whose creation of a 1,282 page, two volume, 55-3/4 pound Bible laid the foundations of the modern world.

Given the state of the modern world, Johannes Gutenberg has a lot to answer for. Marshall McLuhan blamed the split between our tactile senses and our intellect on Gutenberg. McLuhan’s accusation came packed into a virtually unreadable and virtually unread 1962 book called the Gutenberg Galaxy. This was before McLuhan went onto greater things in his Understanding Media, a much simpler book that caught the spirit of the time. Gutenberg’s hold on the mind of man was broken, McLuhan proclaimed, or at least exposed for what it was–a fatal passivity, a closing off the mind to random connections, a distorting rearview mirror. Eventually McLuhan boiled his case down to a single sentence, “The medium is the message.” There was a great fuss about it all and the Canadian academic was soundly thrashed in a dozen learned essays. But McLuhan gave a name to the Age of Media. What we once called the Press, we now call the Media, a fitting semantic revolution to end the age of Gutenberg.

For all its talk about technology, the Gutenberg Galaxy doesn’t say a lot about Gutenberg’s technology. Gutenberg is trussed up as a literary symbol and paraded about the streets of McLuhan’s argument without a chance to speak through his work. We look at a painter’s pictures or read a writer’s books for insight but McLuhan gives short shrift to this inventor’s invention.

Which brings us to the Huntington Library in San Marino, California. the library, its adjacent art gallery and surrounding botanical garden are an enclave of another time set down in the midst of San Marino, the most respectable stronghold of the Southern California wealthy, not the affluent, mind you, the wealthy. It’s only about 10 miles from LA Type Founders on East Pico Boulevard although it seems much farther. Yet there is a very direct connection between the iron-fenced estate of the late Henry Huntington and the last type foundry in Los Angeles. Like the other great “robber barons” of the Gilded Age, Huntington took up Culture win a vengeance, hoping that some of the gilt might rub off his fortune made on the Southern Pacific Railroad and onto his public image. Given time, great wealth has a way of becoming its own justification, if for no other reason than without it, you don’t get places like the Huntington Library. Even the Communist Chinese take great pains to preserve the vanities and extravagances of the old order. The palaces and temples are elaborately captioned so that the touring masses will take the proper lesson. We have our own style in proper labeling.

The Huntington Library’s Gutenberg Bible is in the process of having its label freshened. Normally one volume is kept on permanent exhibition, the two being rotated once a year. When the Main Exhibition Hall is completely refurbished, the two volumes will be continually displayed, side by side. Carey Bliss, who is the Curator of Rare Books and thus the official keeper of the bible, says it is part of a trend in museums to display the major pieces of a collection more openly. Actually, the great bible itself is not in much demand with scholars anymore. A scrupulous facsimile was printed in 1914 and when the occasional request does arise to work on the bible, Bliss says the facsimile is used instead. However, Bliss is only too glad to have volume two loaded onto a gray metal library hand truck for a short private inspection in his office.

Under all that venerability and semi religious aura, the Huntington’s Gutenberg Bible is a very sturdy, very clear, very useable book, if a 22 or so pound book printed on calf skins can be said to be useful. There are 47 whole or nearly whole copies of this bible sprinkled like jewels throughout Europe and the United States, mostly in institutional libraries. Given the insurance rates, the tax laws and the force of scholarly opinion, the handful still in private hands cannot be long for such custody. Two copies disappeared from the University of Leipzig library at the close of World War II. Everyone in the Western book world thinks the Red Army pinched them although the Russians hotly deny it. For the last few years, a copy on paper has been intermittently on sale in New York for an asking price of around $2.5 million. In one of those fairy tales of book collecting come true, a schoolteacher in Gutenberg’s home town of Mainz turned up the first volume of a 48th bible going through an attic two years ago. The bibles differ in their binding, in their hand painted illuminations and whether they are on paper or vellum. What makes them famous is that the text is exactly the same in all of them.

None of the bibles has a word either printed or scribbled into them that mentions Gutenberg. Our entire knowledge as to their probable creator comes from the legal documents that detail the long string of lawsuits that Gutenberg was drawn into during his life. As remote a figure as a 15th century German patrician is to us (and it is wise to remember that in culture and much else, the 15th century was a long time ago), Gutenberg’s life of litigation makes him seem almost modern. The financial underpinning of his closely guarded experiments always came unglued just at the moment when the technical problems were being solved. As a result of a lawsuit, he probably lost control of his great bible to his partner, Johannes Fust, in the very last stages of its five year production.

We know less about Gutenberg’s actual technology than we do of his finances. We know nothing. It is all conjecture. Gutenberg’s wine press probably belongs with Washington’s hatchet. Scholars circle each other growling about the subject but the consensus is that he could just as easily have adapted a paper maker’s press as a grape crusher. Yet we can assume that when Gutenberg lost control of his invention to Fust in 1455, the technique was nearly perfected. Printing spread across Europe in the 15th century faster than anything except the Plague. According to historian James Throe, “By 1500, there were 1,120 printing offices in 260 different towns in 17 European countries, and their output of printed books outran belief.” Throe estimates that in the 45 years after the Gutenberg Bible was printed, 10 million copies of 40,000 different work were produced.

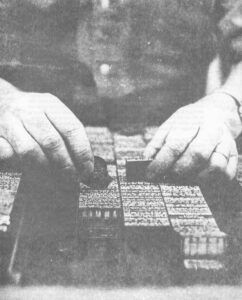

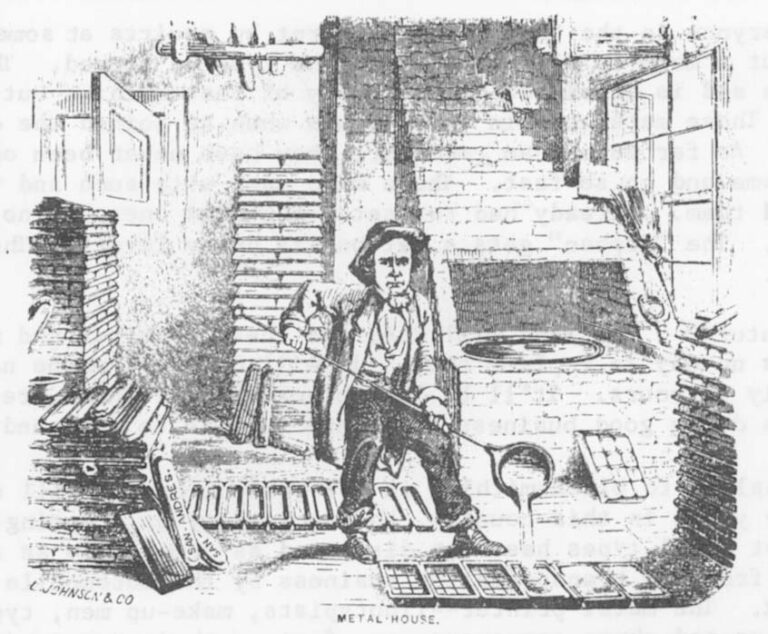

What then was Gutenberg’s great invention? Don Winter of LA Type Founders held it in his hands the other day, unaware that it was a more vivid symbol of Gutenberg than the Huntington’s carefully guarded Bible. Winter had pulled the still warm casting mat out of a Monotype to show a visitor the matrices. They are small squares of brass held in rows like a box of sugar cubes. Punched into the face of each brass cube is the shape of a letter. The machine shifts the matrice over the mouth of the mold. And lead shoots up, forming a negative relief of the letter seated on a long narrow body of lead. Cast as many letters as you need to cover the alphabet. Arrange the letters into sentences. Lock the lines against a hard surface. Ink the type. Lay a sheet of paper on it. Press down with great force for a brief second. You have an exact copy of a bible or a business card.

The one other book attributed to Gutenberg, although on shakier evidence, is called the Catholicon. The colophon at the end makes no mention of the printer but says that in the glorious city of Mainz, this book, “without help of reed, stilus or pen, but by the wondrous agreement, proportion and harmony of punches and types, has been printed and brought to an end.”

Gutenberg cast his letters one by one in a hand mold. Winter runs them off one by one on an automatic casting machine. It is the same process separated by 425 years. Look around at the diminished fortunes of LA Type Founders and realize that in the narrower, true and precise meaning, the Age of Gutenberg is over.

Received in New York on May 31, 1977.

©1977 John W. Fleischman

John W. Fleischman is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from Human Behavior Magazine. His fellowship subject is “The Medium of Print: A Craft becomes a Computer Function.” This article may be published with credit to Mr. Fleischman as a Fellow of the Alicia Patterson Foundation and to Human Behavior Magazine. The views expressed by the author in this newsletter are not necessarily the views of the Foundation.