Scholars may differ but I say that Lynton Appleberry is the inventor of the “Linotypist’s Note”. In 1970, 1 was the editor of my college paper and Lynton did most of the typesetting for it down at the Yellow Springs News. I falsely prided myself on my grammatical taste and thought I had organized a foolproof system of proofreading. I had vowed there would be no typos in my paper. Early on, my proofreaders brought me galleys to point out that the typesetter was changing the copy. My editorial blood immediately boiled until I studied the galleys. Lynton was improving the copy fixing spelling, chopping out phrases of garbled horror, getting some agreement in number and tense. I swallowed my pride but urged my copydesk to greater vigilance.

Then the Linotypist’s Notes started turning up on the galleys. Right in the middle of my lengthy discourses on the college’s enfeebled finances, there appeared parenthetical glosses on the history of the matter under the bold face heading of “Linotypist’s Note.” At first, I ordered them ruthlessly suppressed. When I dropped off the expurgated proofs at the shop of the Yellow Springs News, I caught a glimpse of Lynton scanning the corrected galleys with a pained expression. Even then I couldn’t afford to reject his grammatical aid.

A week or so later, the notes were back. I now realized that the Linotypist’s Notes were filling in vital background. Being young but no fool, I rewrote Lynton’s contributions into the text without credit. I hereby acknowledge my source.

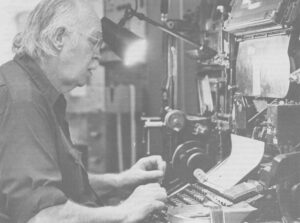

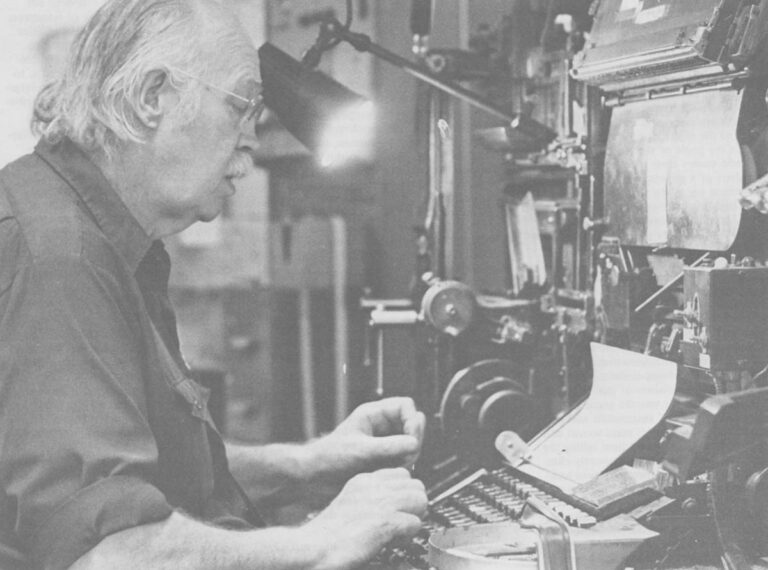

Lynton Appleberry was a legend long before I was made editor. As a raw freshman reporter, I was dispatched on copy runs to the News shop with instructions to hand over my delivery to “the big guy in the green shirt who looks like Ben Franklin.” Today Lynton is still the affable giant in his constant suit of working man’s no iron green. Even in the color snapshots of his daughter’s wedding, you can pick out Lynton as the big man in the green shirt and pants. He still has the Franklinesque wire-rimmed glasses, bald pate and collar length hair although the resemblance to the patron saint of American printers is slightly broken by a more recent white walrus mustache. Otherwise the summer of 1977 found Lynton grayer but looking much as he did 10 years ago when I first laid eyes on him.

But Lynton’s life and times have not stood still and the summer of 1977 found the Yellow Springs News at the end of an era and Lynton uneasy about it. Semi-retired now but eternally philosophical about this world, Lynton was not happy about the decision to convert the News to computer cold type and job the printing of the 2,000-or-so circulation weekly out to a big offset plant in Urbana 30 miles to the north.

Lynton only works regularly on Tuesdays at the News. He goes in around nine in the morning and sets until the copy runs out toward midnight. Then he goes back to his house in the woods outside the village. Lynton keeps the books and his own counsel for the Montessori nursery school that his wife, Valeska, runs in a handsome new prefab building next door. The Appleberrys met at Antioch in the 30s and bought their 15-acre place for a song just before the war. Here they have raised their four children, built the school and a surrounding nature center that they coaxed into a living wilderness from an exhausted pasture. Lynton mows the paths, does odd jobs around the school but mostly passes his time in the house, ensconced in his recliner wedged under a living room window bearing a stained glass panel of a tomato plant. The Appleberrys are fervent organic gardeners — back issues of Organic Gardening, seed catalogs and rural life magazine are stacked to prodigious heights in the house.

Valeska suffers from the traditional nursery school teacher weakness for collecting odds and ends that might turn out to be useful later. The Appleberry house is a warehouse of odds that haven’t come to their ends yet. Valeska is addicted to garage sales — she bought their aged Ford Falcon at one — but only once did she stage a sale of her own. She was amazed when her first and best customer turned out to be the woman in Yellow Springs who was the second-most devoted garage sale shopper. Second to Valeska. When she tells the story, she laughs at herself, “Now who else would it be?”

To Valeska, the greatest change that has come over the News since Lynton’s semiretirement has been the loss of so many of the college papers. Working with the college kids was Lynton’s specialty, she says. Lynton was a teacher to the generations of editors — the ignorant, the arrogant, the unsure, the too clever and the muddlers-through.

To Lynton, it was enjoyable but it was all part of the linotypist’s dilemma — do you save an editor from his mistakes? “Your eye is on letter by letter and word by word so you catch all kinds of stuff.” Then you’re faced with your instructions — “To follow the copy even if it flies out the window–or you can fix it. For Lynton, the answer is usually easy. “You tend to fix it. But you’re not entitled to rewrite a person’s stuff. We just don’t want to print something that god awful.”

Making the customer look good is what Lynton aims at. “You’re trying to tie your customer to you.” The college papers that still come to the News tend to be those where the students have a hard enough time writing the paper, let alone editing it. The delicate touch is required to find out how much aid a college kid will accept. “The person who is the most incompetent and uneducated is the one who gets the most upset if you mess with it.”

The Antioch Record, my old paper, leases an IBM Composer. Sitting on a table in the editor’s office, the IBM replaced the broken-backed sofa on which legendary feats of editorial eroticism were alleged to have been performed. The IBM also replaces Lynton Appleberry. A student typist turns out camera-ready copy on the IBM. The ping-pong table on which I sketched page dummies for later assembly on the make-up stones down at the News has been remodeled into a giant light table. Thursday night, the Record is set and pasted-up in the office. Otherwise the decor is unchanged — cement block walls, posters and secondhand furniture. The current staff keeps their sofa in the outer office. It is in much better shape than the one I remember.

Lynton can see why the Record decided to do their own typesetting and make-up. The cost savings were too attractive to ignore. And he isn’t critical of the paper’s content, which, if anything, is better written than in hot lead days. But the final printed page lacks the sharpness the News gave to it. The type hasn’t the bite and the overall look of the page is a murky gray. “The Record looks like a dirty rag.”

The trouble with today’s college editors, says Lynton, is that they all subscribe to “the modern attitude that it doesn’t matter how it looks. It’s not that they don’t care about quality. It’s deeper than that. They are not conscious of quality. It’s the same reason they can’t spell.”

Lynton shakes his head. “How are you going to stop that and turn it around? There’s all kinds of shoddy stuff going around.”

But then he laughs. “The tide is coming in so let’s all sit down and cry in our beer.”

With his radio-tape player on one hand and a coffee cup in the other, Lynton holds forth on the achievements of his children, the history of the nursery school and the fate of the Yellow Springs News. He has always been a loyal opposition of one at the paper, the observer who prizes the privilege of not being in charge. “I declined to write editorials. I’m not the best writer of editorials. I’m better on the fly. I’m a better criticizer.”

A garage sale electric fan pumps the muggy summer afternoon through the room while Lynton works the dilemma over. “People at the Yellow Springs News have always said, down the road, we’ll have to go to offset. Now they’re saying this is the point. The question is whether that may be down the road a ways.”

The stakes in this decision are immediate. “It eliminates a couple of jobs in the village. Why should we provide jobs for people in Urbana when we’ve got a lot of people in the village looking for work?

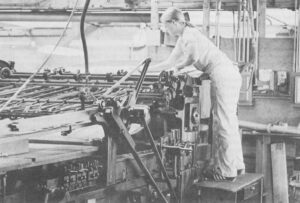

“People have to have work. Right here at the Yellow Springs News, Keith has retired. Eleanor has retired. Zeb and myself have retired. That’s four jobs. If the News had stayed hot lead, there would be a job there for two or three more people. If the Yellow Springs News really tried, they could take on two or three people and stay with the hot lead process. ” He raises his palm as if the jobs were sitting there and then slaps them down on his chair. “You might say that the News just laid down and died. If it came out last week hot type, it can come out next week hot type.”

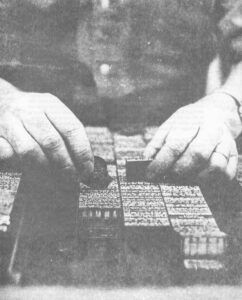

A method doesn’t wear out, Lynton declares. “They used to do it which means they could do it again. If people once used handset type, they could do it again.

“This is running through our whole business system. Everywhere you turn, people are running to buy a machine to replace people. So there aren’t enough jobs.

“There’s something wrong with that philosophy.” It ignores “the social efficiency of machines,” according to Lynton. “I’m in favor of an electric washer over a tub and a washboard. Make slaves of machines. That’s desirable but how are you going to live with it?”

The summer before, Lynton was in Ashland, Oregon, where his son, Kim owns “Appleberry’s Ice Cream Parlor,” Despite the magnificent name, the parlor was barely making ends meet. During his visit, Lynton whipped the books into shape and found the same lesson there. “Kim’s only paying a little more than the minimum wage and the wages are killing him.”

“Undoubtedly, the biggest factor has been wages. This spurs the owners on to develop machines to eliminate the workers. Just think of how many people would be working for the phone company if they still had operators instead of automatic dialing machines,” says Lynton.

“As much as it’s feasible, you want more human work. There’s no politician alive who would say he wants to eliminate jobs.

“To what extent is this whole thing not being resolved on the question of efficiency?

“The little country newspaper was a family thing. The man sold the ads and wrote it up. The wife did the bills. As the kids grew up, they’d work in the shop. They did job printing on Fridays. Now, that was highly efficient. You might also say that nothing could replace it.”

“You might also say that Lynton has described the labor situation at the News. The News workforce is a sort of extended family. All five of Ken’s children have had a hand in the business. His wife Peggy, in fact, does the billing as well as run a linotype.

When they were growing up, the three Appleberry boys worked in the backshop. Bryan who builds log houses in Vermont also works as an offset pressman. Even Rick, the dentist who lives in Ann Arbor, benefited from his printing skills when he took the dental aptitude tests. According to Lynton, “The fact that he can read type upside-down and backwards helps him to look at people’s teeth. You stick that little mirror in there and you’ve got to make sense of it.” Generations of Yellow Springs high school kids swept out the shop, smelted used type, ran the Miehle press and the paper folder. With the press run of the News going to Urbana, a source of pocket money and pocket experience is drying up in Yellow Springs.

The little family-run weekly is no more. “Today you find a high pressure businessman selling ads in four or five locations. It’s for businessmen now primarily, it’s not like the old-time editors.”

What is missing, says Lynton, is an understanding of the parable told by Arthur Morgan, the modern reformer of Antioch and the onetime owner of the Yellow Springs News. As Lynton recalls it, Morgan saw the American economy as a bushel basket of grapefruit. In a basket of grapefruit, there’s room for dozens of marbles. The grapefruit are the ponderous units of conventional ” bigger-is-better” economies; the marbles are cooperatives where people are the capital.

The people at the News were always willing to take lower wages for the cooperative atmosphere of the paper, says Lynton. “What one makes per hour at work is not the key factor. It’s how many hours do you work.

“We’ve been on a big binge. We’ve been badly spoiled. You’ve got to be willing to work for less money or more hours.

“The relatively more hours it takes to make up a metal ad is less than the cost of buying your own (offset) printing equipment or paying off someone else’s equipment. “

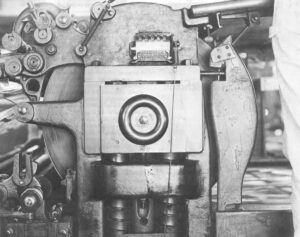

For the last few years, the News had done very well fishing the tide of technology for obsolete hot lead equipment at bargain prices. “They got the additional machines for little or nothing.” Lynton remembers Ken buying a Comet TTS Linotype sight unseen from a shop in Oil City, Pa., for $900. The Comet, which was in excellent condition, cost $18,000 new. When Ken, who was on vacation in the area, dropped by the Oil City plant to inspect his new machine before it was shipped back to Ohio, the owners, sold him a second identical Comet for $450.

“The News has got hardly anything invested in that stuff,” Lynton says. “You could take $5,000 or $10,000 and buy a whole building of hot lead equipment.” Not so with offset presses and cameras. “They don’t give it away. That stuff comes high. It’s hard to see how the News could afford good offset equipment.”

Lynton watches. Lynton reads. His tomatoes grow. A violent thunderstorm sweeps through. Lynton sees radar pictures of the storm front in living color on his set. Hail comes scything down through the woods behind the house, cutting green leaves from the living branch. After the storm, he gets out his tractor and regrades the dirt road. On Tuesdays, he sets type at the News. At home, he watches a PBS documentary on nuclear power. He follows Johnny Carson into the small hours. He reads an account of life on a stonewall New England farm. Lynton studies a TV report on the arrest records of New York’s blackout rioters. He returns to criticizing. “I’m not trying to talk like a socialist or a communist but you’re faced with the problem that people have to live.

“Right now there aren’t enough jobs in this country. Somehow those people have to have an income. Society has to provide a living for those people. Either that or kill them and let them die.” Instead, Lynton says, we make jobs for people to care for people who have no jobs. Look at food stamp bureaucrats.

“All along the line, you’re putting your head into the jaws of the lion,” Lynton warns.

“You may say that the southern planters and the Egyptian kings were living on the labor of slaves. And you could say that the West might have a good life living on the labor of machines. But this is going to get worse.

“The way Western society is going is that you build as many machines as you can. You employ as many people as you can and those you can’t you give them bread to control them.

“We used to have slaves and now everyone agrees that was wrong. Now we have machines for slaves and everyone agrees that is good. But the trouble is we’re slaves to the machines.”

The lure and the promise of technology, according to Lynton, is “Do no work in the new Garden of Eden.” Lynton goes into the kitchen to get another shot of coffee from the Thermos. Outside, the crickets howl in the night woods. It is finally cooling down.

“I believe in the simpler life,” says Lynton, “and I just don’t know how this is going to be resolved.”

©1978 John Fleischman

John Fleischman is spending his fellowship year studying