Present Indications and Past Intimations

In the small hours of Wednesday, April 20th, a supervisor walked into the Computer Operations room of the Los Angeles Times, carrying a cup of coffee. The supervisor was a very tall man — six foot six and, in the way that the tall have of putting things out of the reach of harm and the short, he parked his cup atop one of the computer banks of the main IBM 370/158, and went about his business.

Enter a short man bearing cardboard boxes and looking for a safe place to store them. Unable to see the lurking coffee cup, the box-carrier chose the very same computer bank as a suitably inaccessible place for his burden. On tiptoes, he pushed the boxes up. The cup fell in such a way that most of its contents went right to the very heart of the machine. The entire 370/158 system went down.

A repairman was turned out of bed. Over the phone. he asked his first sleepy question. “Did the coffee have cream and sugar?” The question was hurriedly passed down the line of command to the tall supervisor who, by this time, was probably wishing he was either shorter or elsewhere. “Both,” was the reply passed back up the chain. “Then you’ve got some problems” said the repairman, getting out of bed.

What followed over the next few days was a highly commendable team effort in improvisation and flexibility as the Times fell back on the older, slower and more limited 370/145 computer. All but the most essential users were ordered off the system. Extra shifts were called in and sent home and then called back to keep pace with the back-up computer’s slower digestion. Deadlines were shifted, priorities rudely apportioned and somehow the Times put out all editions, roughly on time. Meanwhile, repairmen had circuit boards stacked up like cards against the walls as they ran diagnostic programs through the wounded 370/158. Spare parts were airlifted in from the East and, by Friday, the main channels were cleared and the 370/158 came back on line.

What all this cost the Times is a dark corporate secret. The actual cost of the damage to the computer was covered by the paper’s $1,000 deductible insurance policy on the unit. Many of the computer’s suspect innards were later retested and found to have escaped the rampaging sugar crystals. Officially, this one cup of coffee with cream and sugar cost the Times $40,000 in lost classified ads, newsstand sales, repairs and overtime. The internal Times grapevine touts a much higher figure. The $40,000 figure is rather conservative, given the dimensions of the disruption and the normal volume of business. But then the paper’s conglomerate owner, the Times-Mirror Corporation, which reported nearly $70 million in after-tax profit last year and is confidently expecting 1977 revenues to go over $1 billion, can afford it.

Those most intimately involved with the computers saw the whole spectacle as a victory of sorts. The computer system took a terrible blow but came through. Loyal employees rallied to the emergency. One dayside crew of typists and proofreaders came in Thursday morning, overloaded the back-up computer in three hours, were sent home to come back at 1 a.m., worked through the night and were let go by 8 a.m. and reported back for another shift at 5 p.m. The tall supervisor held onto his Job although the prohibition against food and drink in the Operations Room was redoubled.

That is the real life story of the coffee cup disaster but if the accident had occurred a few years before or if life had the dramatic sense of an oldtime Hollywood epic, that is not what would have happened. Imagine coffee dripping down the face of the IBM nameplate. Imagine the composing room foreman striding onto the floor, shouting, “Get your aprons, boys.” T-squares and ruling tape are tossed aside. The paste-up easels are cleared from the tables and the old hardware of chases, leads and quoins are dug out of backrooms. Linotypes are uncovered, hastily rewired and plumbed. The melting pots are fired up as the veteran linotypists desert their dead electronic proofreading terminals. The tinkling of brass matrices is heard again in the composing room. The galley trays fill up with slugs of shiny lead. Ad Row is alive with make-up men carrying type to their assigned “dumps” to assemble the ads. Page One is assembled and locked tight. The camera pans across the room. Nothing can stop the power of the press. The music swells.

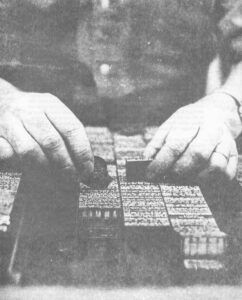

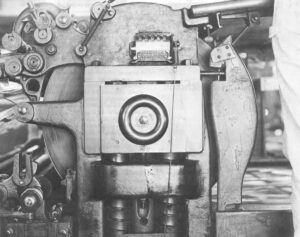

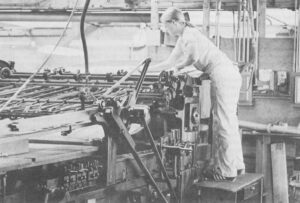

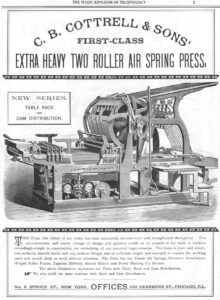

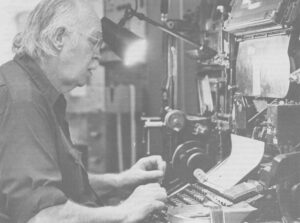

Alas, the dear dead days are beyond recall at the Los Angeles Times and nearly every other newspaper in the United States. The dirty, noisy and bewildering hot lead Composing Room through which countless school children trooped for a look at its bizarre machines and highly skilled inhabitants has nearly disappeared from this country. It survives only in isolated cases such as rural weeklies where the circulation is too small and the cost of the new electronics too high or in a few big city dailies such as the New York Times where strong craft unions resisted the change to the last ditch. That last ditch has been overrun and every day more video display terminals (VDTs) sprout in previously forbidden areas. The last handful of newspaper linotype machines is being trucked off to oblivion and South America.

The Los Angeles Times never had any unions to overrun. A policy of tireless anti-unionism and generous salaries kept the LA Times’ production department open to whatever innovations technology could concoct. On the night of the coffee cup, there was only one linotype machine in the whole building. It was undergoing a loving reconstruction to serve as the central exhibit of a working hot lead museum. Given enough linotypes, the dwindling number of trained compositors would have been hard pressed to set the mountain of classified and display ads, let alone all the editorial copy. Even then, there probably wasn’t enough lead in the downtown plant to set it all. No, the make-up men and compositors could only soldier on in their new positions-keyboarding, pasting and proofreading. Perhaps they shared a scornful laugh among themselves but that was it. Hot lead is dead in newspapers. Coffee cups and power failures may expose the vulnerability of the new order but there is no going back, no hoping for a sudden restoration of the old skills and crafts.

Sometimes technology heralds itself with a fireball over Japan or a television picture from the moon but usually it comes padding into our lives on quiet feet. The coming of the next wave of the new technology at the Los Angeles Times is being directed from a small office just off the City Room. Larger quarters are promised but in the meantime, the somewhat grandly named Editorial R&D Room is packed with three desks, a changing collection of operational and prototype computer terminals and a blackboard. It is the office of Will Locke who is a News Editor. Locke is in day-to-day charge of the design and installation of a “front end” system. The LA Times is calling theirs the News Editing System (NES) but many newspapers have already converted to and many more are in the process of acquiring similar set-ups. The NES will create an electronic newsroom for the Times by replacing the typewriter with the video display terminal (VDT), the pencil with the phosphorescent cursor and copy paper with the data storage bank. It will change the news department from paper shuffling to information processing. The editorial front end system and its expected yet still unperfected sibling innovation, full page pagination, will all but eliminate the composing room. Add to these, the next generation of technology that promises direct plateless printing, satellite plants and ink-jet technology and there are many in the newspaper industry who predict with confidence that in 20 years, there will be no such category of employee as “printer.”

Locke shares his office with a printer, Herb Mann, who used to be the foreman of the Composing Room. Mann was assigned to help Locke for six months. Two years later, he is still helping. On a recent Friday, Locke and Mann were joined in their small office by Jim Robertson who is a systems analyst from the Information Systems Department. An editor, a printer and a computer analyst, they had come together to discuss the weather. Or rather how to set the weather into type. Or even more specifically how to set the daily chart of world-wide temperatures and precipitation. A newspaper is filled with tiny tables of vital information-ship movements, baseball scores, tides, sunrise-sunset, stocks, etc. It’s the sort of service that very few readers specifically buy a newspaper to read but it’s also the sort of thing that brings in outraged complaints if omitted or even moved to an unfamiliar place in the paper. Tables can be nasty little devils to set. While they take up about 10 percent of the daily newspaper, they can also take up an inordinate amount of production time.

The chart of highs and lows was the subject of the meeting in Locke’s office. The Times has run the temperatures and precipitation from the same list of cities for years. Every day, someone has to set the same names with the changing temperatures after them. Originally, a compositor set them directly on a linotype but was later replaced by a tape punch typist. The perforated tape was fed to an automatic linotype. Since the Times went all cold type at the end of 1974, the same weather stats are prepared, as usual, in Editorial and then passed to Production for retyping into a special optically scannable typeface. The story is then fed to the computer to read and remember. On command, the computer drives a phototypesetter which “outputs” the corrected tables on long strips of photographic paper. The result is cut out and waxed into its place next to the obituaries so the tiny percentage of readers who want to know can read that it got up to 79 degrees in Columbus, Ohio, from a low of 46 degrees but it didn’t rain.

The News Editing System will eliminate the production department as middleman. Where once a skilled compositor and now a semiskilled typist “keyboarded” the story from a piece of paper prepared in the Editorial Department, a news clerk will enter the highs and lows directly onto a computer terminal complete with directions on what size type, what width column and what space between the lines the table is to be set in. This is known as “saving keystrokes” and is the cutting edge of the new technology. It is not merely automating a process so that a machine does on its own what it used to do under an operator’s directions. A front end system skips an entire layer of the process, like frying eggs directly on your plate and eliminating frying pans. The effect on an individual depends on whether you are more interested in eating than in working as a cook. The discussion in the Editorial R&D Room was about writing directions for the computer in how to “fry” the temperatures from Columbus.

Roughly speaking, Locke as the representative of the Editorial Department was concerned that the charts come out the way they have always come out, Mann as Production Department representative was presenting his recipe for creating weather charts and Robertson was there to make sure the format was the most efficient use of the computer’s capabilities. This procedure is not to be confused with programming which is translating human instructions into the language of the computer. Mann was presenting a “preset format” that would be followed by the news clerk at his terminal to enter the weather. A program would later be written by the supplier of computer “software” so that anytime the editor entered the information with instructions to call up the format, the computer would output a weather chart. Since a computer can remember the thousands of traditional ways type is arranged, the editor is only concerned with entering the correct information. The computer will then put it out in the preset format. The computer is not merely replacing the labor of a human typesetter but his knowledge as well.

Mann wanted the computer to hang onto the unchanging vertical list of cities so that the editor need only type in the changing statistics horizontally. It is one of the smallest wonders of the NES yet the three men went over Mann’s format with great deliberation. The problem was whether the weather was the only application of this particular vertical preset text or was it adaptable for use in other tables, say the boxscore of a Dodgers-Giants game? So Mann erased his list of hypothetical cities with their highs and lows to chalk up a hypothetical baseball boxscore. The problem here was that while the game summary is always a two line entry, the roster has as many vertical lines as there are players. They went round and round on that until everyone agreed that baseball scores were a different matter.

Finally Robinson conceded to Mann that the problem he thought he saw was not really a problem. “Go ahead,” he said, “write it up.” Vindicated, the white-haired printer pushed the yellow chalk back in the blackboard groove. The new age was a step closer.

An editor, a printer and a systems analyst are a fairly odd working party by the traditional standards of newspaper organization. But traditional boundaries are breaking up in the newspaper business because the electronic technology defines the work differently. Nearly every newspaper in the country has technology committees similar to Locke and company-editors who struggle with typesetting, printers who write computer formats, and computer analysts who study newsgathering.

Will Locke is an example of a new kind of newspaper man, what Allan M. Siegal who performs much the same function at the New York Times calls a “news room ambassador to technology.” Locke became a technological diplomat almost by default. Through high school, Locke had been a sports stringer for the Santa Rosa Press Democrat. Locke went newspapering full-time after running out of money at Stanford. He worked on a Bay Area newspaper called the Weekend Hunting and Fishing News before joining the Oakland Tribune in 1956 in the exalted position of’ Night City Rewrite Man. he soon went “on the desk” and began the long climb to Assistant Managing Editor. During this time, the strange technological doings that had the unionized Composing Room of the Tribune in an uproar began to spill over into the News Room. Previously new machinery was something management types discussed with the men wearing aprons in the shop. upper level editors were involved but the mass of editors were usually concerned only with typefaces and deadlines. Suddenly Locke and the other desk editors were dragged into meetings about photocomposition, optically scannable copy and the difference between a bit and a byte. Locke remembers, “The new technology was such a horror to the writers and editors that I decided to explore everything on the subject.” The technological education of Will Locke was largely a self-administered affair. He read the articles and books that supposedly explained the Brave New Future. He went to the trade shows to see the latest marvels and to interrogate the salesmen offering attractive terms on the cybernetic millennium. It was a confused time that seemed to get even more confusing as the technology speeded up. Manufacturers were hungry to recoup development costs on equipment that was state of the art one day and obsolete the next. Publishers fervently embraced the gospel of technology but were dismayed when sudden innovations left them with perfectly useful outdated machines. Automating hot lead was the goal of many large newspapers through the early sixties until improvements in photocompositors and plate makers made cold type the “coming thing.” Today, the “front end” electronic newsroom promises to do away with the Composing Room altogether.

Showing both interest and aptitude for the new technology, Locke represented the Editorial Department in the Oakland Tribunes conversion to cold type. Then in l973, he was hired away by the Los Angeles Times.

The Times was in the midst of its cold type conversion when Locke arrived. Hampered by the sheer size of the newspaper, the Times did not go all cold type until the end of 1974. Locke and his colleagues were then free to plan the front end system that became the NES. The sheer scale of the Times today remains the main challenge to Locke. “This paper is so big, it’s like four or five newspapers under one roof. Each department has its own peculiarities.” The key to successful technology, says Locke, is matching the system to the user’s peculiarities and not the other way around. “It can be bad if the user is never consulted but where the user is considered, it can’t be bad.”

With so much equipment to buy and with so much money to spend, the Times has the commercial leverage to custom design their own system. “We have taken pains to see it meets the requirement of the staff. We are not buying something off the shelf and dumping it on the staff.” Editors and reporters were briefed on the possibilities of the new system, then invited to play on production terminals set up around the newsroom and finally surveyed for their ideas. Having defined the needs of the users, the NES specifications were drawn up. The Times has selected the Data General Corporation as the vendor of the NES. Data General will subcontract all the pieces they can not supply directly as well as overseeing the installation and fine tuning of the system. Computer systems come in two parts-the hardware being the computers, their storage units, their connections, the photo printers and the terminals; and the software being the programs that are the brain and memory of the system. The NES specifications are extremely complex. They set out the Times’ demands for reliability, back-ups, security, interfaces and more. Essentially the Times is saying this is what we want and it’s up to the suppliers to create or adapt products to fit.

The video display terminal is Locke’s special pride and the specifications for it envision a Rolls Royce of terminals. Locke shows off a sketch of the keyboard and runs down many of its many features. The heart is a standard electric typewriter keyboard surrounded by a thick hedge of command and special function keys. The screen will split in two so that separate stories can be compared and pieces of one can be slipped into the other. It will have “virtual scrolling,” the ability to roll the story up or down the phosphorescent screen as if the story were written on a phantom roll of paper hanging out the back. Writers will do all their writing on the terminal. Editors will fix stories, give typesetting instructions and write the headline directly on the terminal. The list of features goes on and on. The bridge writer will have the symbols for hearts, clubs, diamonds and spades at his fingertips. Stories that mention the island of’ Curacao will have their very own cedilla. The screen will meet OSHA standards for permissible x-radiation. Locke emphasizes that the terminal is adapted to the lowest common denominator of user, “the hunt and peck typist” writing a one paragraph short on a local narcotics raid as well as the editor creating a single story on arms control negotiations out of wire service reports.

The NES will take two years to finish and will cost the Times at least $4 million, all of which had to be Justified in advance to the Financial Department in a laborious “return on investment statement.” Locke says the system will pay for itself in manpower savings and increased productivity), within four or five years.

By which time, parts of it will be obsolete. Guessing right is an important element in technology shopping. The star exhibit at one trade show will be the infamous talk of the next one. New equipment is often outdated by the time it is plugged in, the manufacturer having come out with a few new features after the original order was placed. In drawing up its specifications, the Times deliberately reached ahead for features that are not commercially ready yet. Locke has spent a year describing a system that doesn’t exist but one that will be adaptable to even newer technology still in the experimental stage. The NES specifications anticipate the eventual perfection of a process called pagination. Instead of pasting together the final page out of separate stories, a full pagination system would make up a page of editorial matter on a screen and then, at the press of a key, drive a photocompositor to put out the finished page in a single sheet. After months of work, the Times now paginates their voluminous classifieds but the ability to do the front page in a similar fashion is still to come.

When pagination does come, newspaper cut and paste make-up will be as obsolete as the metal craft it replaced. Besides the savings in labor and time, pagination will also complete what Locke feels is the most important element of the electronic newspaper. “The Editorial Department will have almost total control of the product.” The News Room will write, edit, typeset and make up the newspaper on their electronic terminals. The complete page will only take on physical or “hard” form when it is ready for printing. And that, says Locke, opens the way for the next step-plateless printing. The process of changing a paper page into a printing plate would be bypassed. This still unborn generation of presses would be more like giant Xerox machines with either a printing surface controlled by lasers or an extremely high speed ink jet to spray out each copy. What is being “printed” would be controlled directly and instantaneously from the Editorial Department. Stories could be updated while the presses are running. A central printing plant would no longer be necessary as satellite presses could receive their pages electronically. Special editions could be tailored to the locality served by that satellite plant. The expense and time consumed today by newspaper trucks clawing their way out of congested cities would be saved. Editions could close much later so that the newspaper that lands on a subscriber’s doorstep would contain fresher news. Information would only be an hour or two old instead of the eight or so hours that it now takes the Times to shoot plates, print and truck copies out to the distributors. Beyond that, there is the possibility of skipping printing presses entirely. Your future television set could receive electronic pages from the “newspaper” and then print them out in your living room. “Extras” could break while you are still on your first cup of morning coffee. Newspapers could lessen the timeliness edge that television news currently enjoys. All the way, there would be fewer paste-up artists, camera men, plate makers, pressmen, truck drivers, and newspaper bundlers.

Televisions that print newspapers are technological novelties, curiosities that draw crowds at conventions. But pagination is fast approaching that magic point where technical capacity crosses the graph line of economic feasibility. Given the direction of things, Locke doubts that in 30 or even 20 years, there will be newspaper employees who call themselves printers. The typographic skills of the printer are being absorbed into computer formats but Locke believes, “It’s still going to take skilled people to prepare formats for people to use.” Titles will change but specialists who retain the printer’s eye for good printing will remain in newspapering, only they will be working in the News Room instead of the back shop. “The craft that once resided in the Composing Room is now being reassigned to the Editorial Department.”

(To be continued in JWF-3.)

The text was set on an IBM Selectric Composer in Bodoni Medium by Mrs. Hazel Richmond at the Department of Journalism, University of California at Los Angeles.

Received in New York on July 25, 1977

©1977 John W. Fleischman

John W. Fleischman is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from Human Behavior Magazine. His fellowship subject is “The Medium of Print: A Craft Becomes a Computer Function.” This article may be published with credit to Mr. Fleischman as a Fellow of the Alicia Patterson Foundation and to Human Behavior Magazine. The views expressed by the author in this newsletter are not necessarily the views of the Foundation.