The cover is adapted from the American Bookmaker, Nov. 1892. Column headings, ads and other illustrations are from the same magazine. Lay-out by John Fleischman.

ANAHEIM — The elderly gentleman and the respectable lady looked more like chaperones than security guards. Dressed in red blazers that marked them as ushers at the Anaheim Convention Center, they stood to one side of the conference hall doors, nodding politely to the throngs of publishers, editors, production supervisors, equipment manufacturers, corporate financial officers, computer analysts and sales representatives flowing past them into the opening session of the 49th Annual American Newspaper Publishers Association Research Institute (ANPA/RI) Production Management Conference. Surveying the crowd, the respectable lady made the immediate and astute observation. White gloved hands folded before her, she whispered to her companion who stood with hands folded behind him, “There aren’t very many ladies here.”

Indeed, there were not. It wasn’t strictly a stag affair — ANPA/RI did have Helen Copley on the opening panel — but the few women attending the conference were outnumbered by the women waiting on its needs — typing name tags, serving coffee and handing out sales brochures. But then nobody was in Anaheim to discuss affirmative action. The nearly 12,000 “attendees” came not to talk people but to talk machines. It is important to remember that the organizer of this convention was the Research Institute. The parent ANPA has its own convention every year where the publishers can pass resolutions against postal rate increases and ponder new schemes to increase circulation. A. J. Leibling used to find numerous similarities between the ANPA convention and the Barnum & Bailey circus. But that was in the days before the Ringling Brothers and the electronic newspaper. Headquartered in Easton, Pennsylvania, far from the straight-forward lobbying activities of ANPA in Reston, Virginia, the Research Institute concerns itself with the nuts and bolts of’ manufacturing newspapers. Only today there are fewer nuts and bolts used in printing newspapers and many more silicone chips and polymer plastics. The ANPA/RI Production Management Conference is a totally different show, featuring not three rings of trained animals but three giant exhibit halls of the very latest newspaper hardware and software.

Indeed, there were not. It wasn’t strictly a stag affair — ANPA/RI did have Helen Copley on the opening panel — but the few women attending the conference were outnumbered by the women waiting on its needs — typing name tags, serving coffee and handing out sales brochures. But then nobody was in Anaheim to discuss affirmative action. The nearly 12,000 “attendees” came not to talk people but to talk machines. It is important to remember that the organizer of this convention was the Research Institute. The parent ANPA has its own convention every year where the publishers can pass resolutions against postal rate increases and ponder new schemes to increase circulation. A. J. Leibling used to find numerous similarities between the ANPA convention and the Barnum & Bailey circus. But that was in the days before the Ringling Brothers and the electronic newspaper. Headquartered in Easton, Pennsylvania, far from the straight-forward lobbying activities of ANPA in Reston, Virginia, the Research Institute concerns itself with the nuts and bolts of’ manufacturing newspapers. Only today there are fewer nuts and bolts used in printing newspapers and many more silicone chips and polymer plastics. The ANPA/RI Production Management Conference is a totally different show, featuring not three rings of trained animals but three giant exhibit halls of the very latest newspaper hardware and software.

Walt Disney is more in the style of the Research Institute than P. T. Barnum. Anaheim is, after all, the home of Disneyland which was packing them in at record levels just up the road from the Convention Center. The RI Production Conference is a Magic Kingdom unto itself where the New Technology is king. For years, the Research Institute has been proclaiming the coming of the electronic newspaper, promising that it would be something else and by gar, it is. The New Technology has cut costs, raised productivity and given the industry room to maneuver in uncertain financial times. If the crowd and the opening session speakers sounded a trifle smug, they had cause. Joe D. Smith who is President and Chairman of the Board of ANPA boasted to them, “The New Technology can do almost anything. The one tough decision we have to make is what do we want done.”

There might be one or two other tough decisions down the road but Chairman Smith was expressing the common feeling that the new technology had given newspaper publishers control over their destiny. Technology has only to be pointed in the right direction and wonders will be worked. For one thing, Smith pointed out that, “There is no longer the protective cloak of crafts and skills that once seemed to insure lifetime employment.”

All this was not news to his audience for Chairman Smith was speaking to the converted. The newspapermen sitting out there on thousands of folding chairs were devout converts and disciples of the new technology. They had come to the earlier production conferences, been shown the light and taken the electronic marvels home.

“I am convinced,” Chairman Smith told them, “that you ain’t seen nothing yet.” Most of the audience hadn’t and was getting a trifle impatient.

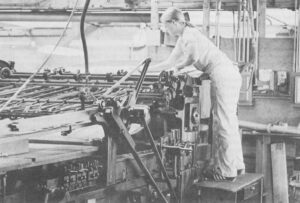

Speeches and panels were the secondary attractions that drew “attendees” from all over North America as well as the advanced technology countries. The big draw at these production conventions awaited them behind guarded doors — a massive exhibition covering 270,000 square feet of computer terminals, lasers, composition systems, presses, plate makers and assorted electronic and mechanical wizardry. Outside of the equally massive international DRUPA ’77 trade show going on at that very moment in Dusseldorf, Germany, ANPA/RI had the very latest of the very latest in what money and corporate ingenuity can devise to print newspapers. With the occasional patch of Japanese and Western European competition, ANP/RI was 5.2 acres bearing a bumper crop of American technology.

Shortly before the noon gate-opening, a busload of off duty stewardesses arrived and hurried past the guards to take up their places inside. Finally the men from North Dakota and Alabama and Taiwan and Oregon were unleashed inside this temporary adult amusement park. The stewardesses were waiting, spiel in hand. The Harris Corporation had drawn the area directly opposite the main doors and for the next four days, a smartly attired flight attendant between flights exhorted one and all, -Welcome to the Wonderful World of Harris.” The cry with suitable modifications was taken up by sales reps and engineers from the other wonderful worlds of addressograph Multi-graph, Agfa Gevaert, AT&T, Canon, Compugraphic, Dow Jones, Dupont, Eastman Kodak, GAF, W.R. Grace, Hendrix, IBM, 3-M, Mergenthaler Linotype, Rockwell International, Raytheon, Sperry Univac, and Texas Instruments to name but a few.

Like Disneyland, the ANPA/RI show has a flair for the spectacular. A Japanese company had a Complete rotary press unit Set up to run. A heavy machinery moving company showed off its hoisting capabilities with a red biplane suspended in mid-air. A Swiss-based company that makes mailroom machinery erected its prize conveyor system against a wall of mirrors creating a giant double mobile.

Once the first-time visitor got used to the scale of the exhibits and the slick design of nearly all of them, it was the “front end systems” that drew the longest examinations and the second trips back. A front end system is the doorway into the Wonderful World of the all-electronic newspaper. A system is made up of the computer terminals that replace the typewriter and the pencil in the city room and the software data base and computer-driven output devices that replace the linotype in the composing room. (See JWF 2 & 3.) While the giant technological corporations dominated the exhibit floor, there were many small and medium sized outfits on hand from the high technology strongholds such as Route 128 around Boston, or the computer chip paradise around San Jose, California known as “Silicone Valley.”

There was a curious democracy at work. As long as there were no obvious high-rollers around, the sales reps were only too glad to lay their honeyed line in your ear, urge you to sit down for some “hands on” experience with their marvelous machines and fill you in, sotto voce, on the shortcomings of their respected competitor across the aisle.

Not until you’ve sat down at an editorial VDT (video display terminal) and used up some of the free computer time that is being pressed into your ignorant hands can you understand the significance of the television screen set atop a bank of’ typewriter keys. You are seated before a computer designed to serve the wordsmith. The salesmen tell you over and over that the ordinary reporter or editor doesn’t have to understand the machine’s loic. The machine has been carefully taught to speak your language and the computer terminals at ANPA/Rl speak newspaper language. Sitting down to play at the terminal of a fairly complex system can make the first-time writer a little giddy. Even without understanding a tenth of’ the system’s programmed capacity, the initial response is gee whiz. Once you are told how to say hello to the VDT, the screen opens, up your file. You can write stories here, or store notes or put away pieces of work until you’re ready to bring them out. Once you punch in your code, you can start writing but it’s not with a fading typewriter ribbon but a moving dot of light called a cursor. ‘The cursor is strongly reminiscent of the way Tinkerbelle was done on the stage in “Peter Pan” — a moving spot of light flitting about doing magic. The cursor is usually controlled by shift keys clustered in the pattern of a compass. Little arrows show how each button controls the cursor’s movement in one of the cardinal directions. Up, down, left, right, you nudge the cursor along, fixing and changing, dropping a word here, inserting a word there.

Of course, the writing doesn’t get any easier and the reporter using a VDT has the same task to perform only on a very expensive electric typewriter with an unlimited correction ribbon. A VDT will not go out in a rainstorm to cover a train wreck. It wouldn’t develop a single new source in the county sheriff’s office. A VDT is more of all editor’s tool to process copy faster and cleaner. For the writer, the rest is novelty.

This is not to underestimate novelty. The sheer size of the exhibit became a challenge to the first-time visitor. The whole floor had to be covered. All the keyboards had to be tried and all the promotional literature collected. The veterans of previous shows were also under a compulsion to see it all. If your newspaper just bought a Hendrix, you had to go past Mergenthaler to see if they had a better system. And somewhere out there, lurking amidst all the plexiglass and printed circuits, there might be the breakthrough device to cut costs, increase productivity and convince your publisher that you are the technology spotter of all time.

There was also a Christmastime-in-the-Toy-Department air to the exhibit. Many came to Anaheim with their newspaper’s money burning a hole in their pocket. They shopped the floor with the intoxicating mission of spending a great deal of somebody else’s money on a very sophisticated machine. The sales reps were waiting. It was not the milk of human kindness but the cash of human commerce that brought all these manufacturers here. ANPA/RI, which keeps track of these things, surveyed 443 newspapers in the U.S. and Canada last year to find out how much they spent on plant expansion. The papers reported shelfing out close to $200 million for plant expansion in 1976 but nearly three quarters of that — $146 million — was for new equipment. This year, a group of 437 papers predicted they would spend $258 million on expansion with $180.6 million of that for equipment. A look at the figures for the editorial department alone explains why so many companies are trying to get into the “front end” systems market. In 1976, the papers surveyed said they spent $10.6 million on new equipment for their editorial departments; in 1977 they were expecting to spend almost twice as much — $20.5 million. Throw in the $29 million spent on new composing room equipment each of the two years and you can see why hot lead technology is not dying a lingering death but succumbing to a heart attack.

That kind of money has attracted many newcomers, both great and small, to the newspaper equipment business. The so-called high technology companies, in particular, have found the field suited to their talents and economically worth their efforts. High technology is almost a synonym for aerospace and weapons contractors. The boom and bust nature of the sword business has driven many weapons manufacturers into the plowshares trade. Many of the ANPA/RI exhibitors are visible proof of the doctrine of diversification that is so fashionable in the U.S. corporate defense establishment. Much of the technology for sale in Anaheim is a direct spinoff from government and military work. The CRT screens and systems software designed to shoot down Russian fighters over Prague are, in their second generation rebirth, setting obituaries in Kansas and composing grocery ads in Boston.

Newcomers to the newspaper equipment business such as Raytheon which makes everything from Amana microwave ovens to Sparrow air-to-air missiles had a large and heavily congested exhibit at Anaheim. Raytheon only became interested in newspapers in 1973. Traditional printing machinery suppliers such as Mergenthaler Linotype have had to scramble to overhaul their engineering capabilities for the jump from the mechanical to the electronic printing age. Other traditional suppliers have been absorbed into technology conglomerates as Goss was swallowed by Rockwell International or have transformed themselves from printing manufacturers into communications technology brokers as the Harris Corporation has done.

Harris is the very model of’ such a modern major conglomerate. Within the bounds of its own history, Harris is almost the Everyman of American industry, changing from a midwestern manufacturer of printing presses to a Sun Belt-based advanced technology complex. The Harris Automatic Press Company was started in 1895 in Ohio by two brothers in the Jewelry business. They were the classic Yankee tinkerers who first modified a local newspaper press and then went on to design their own. Harris Press took off in 1906 when it introduced the first practical lithographic press to be manufactured in the U.S.

Harris is the very model of’ such a modern major conglomerate. Within the bounds of its own history, Harris is almost the Everyman of American industry, changing from a midwestern manufacturer of printing presses to a Sun Belt-based advanced technology complex. The Harris Automatic Press Company was started in 1895 in Ohio by two brothers in the Jewelry business. They were the classic Yankee tinkerers who first modified a local newspaper press and then went on to design their own. Harris Press took off in 1906 when it introduced the first practical lithographic press to be manufactured in the U.S.

In 1926, the company began broadening its hold on the printing business by merging with smaller press and printing machinery companies to form the Harris-Seybold-Potter Company. Potter disappeared from the corporate name in 1946 and Seybold in 1957 when Harris acquired the Intertype Company, the great rival to Mergenthaler Linotype founded by a group of newspaper publishers eager to break Mergenthaler’s monopoly when the original linotype patents expired in 1917. Harris acquired Intertype almost at the high-water mark of hot lead technology but it also produced offset presses, bindery systems and other equipment that gave it a powerful position in the graphics field.

The same year Harris became Harris-Intertype, the company broke out of the narrow confines of the printing field by purchasing Gates Radio, which is now the nation’s largest maker of radio transmitters and the number two manufacturer of television station equipment and transmitters. Thus Harris adopted a strategy of locating a potential market and then buying up a smaller company that had the technological expertise in the area. Under this plan, Harris acquired smaller companies in data processing, microwave technology and advanced communications. The key merger in this program came in 1967 when Harris made a deal for Radiation Inc., a highly sophisticated space communications firm head-quartered just down the coast from Cape Canaveral in Melbourne, Florida. The Radiation Inc. name disappeared into the corporate persona along with Intertype, Potter and the others when Harris became just plain Harris in 1974. The question of who took over whom in the Radiation deal remains. As Business Week points out, five of the seven current top officers of Harris started out at Radiation. The 1,000 scientists and engineers from Radiation became an internal cadre that accelerated Harris self-transformation.

The Harris entry into the electronic-editing field is a classic illustration of crossover technology. In 1969, a single Harris executive was dispatched to Melbourne to poke around the plant in search of an idea for a commercial product that could be spun off from the space and military hardware being developed there. A unit designed for military cable traffic became the prototype for the Harris 1100, the first electronic editing terminal. Working with UPI and Gannett Newspapers, Harris put the 1100 on the market in 1970 and the rest is history.

Today 75 percent of the company’s sales are in electronics. Over the past five years, their electronic product sales have grown at a rate of 15 percent while printing equipment sales have increased by only 8 percent. To emphasize the company’s new look, Harris announced in October that it is moving its last 350 corporate headquarters employees from energy-embattled Ohio to Florida to join the mass of its scientific and engineering employees.

Harris has contracts from all three branches of the armed services. For the Army it is building something called an Advanced Surveillance Target Acquisition and Night Observation Systems Data Link. The Air Force is getting an extremely complex weather recording system and is already using Harris equipment for aircraft communications. The Navy is currently its largest single customer. The contract for a Versatile Avionics Shop Test (VAST) system that will electronically check out Navy airplanes on carriers and land bases has grown to $400 million since its start in 1963. Harris is also a major defense subcontractor such as the $7 million deal it has with Lockheed to equip 18 Canadian long range patrol aircraft with a version of their avionics test system.

Their record is not spotless. Harris was a large subcontractor on the recently aborted B-1 bomber. Last year, an SEC-required audit turned up $1.8 million in questionable payments” both foreign arid domestic over six years that greased the wheels of commerce for $32.5 million in contracts. In 1975, corporate earnings were hoist on the petard of’ technological change when Harris waited too long to get rid of an Italian subsidiary that made obsolete sheet fed presses. That mistake cost the company S17 million in losses and dropped their 1975 profits to $852,000.

But Harris has rebounded. In the fiscal year that ended last June, Harris posted record sales of $646 million and earnings of $40 million. Its commercial satellite communications sales which grew out of’ the Radiation Inc. work for NASA were up to $45 million. Satellite communication are widely touted as the challenge to the telephone for common carrier traffic, particularly in computer to computer exchanges. Harris is deeply involved with the plans of the Associated Press and United Press International to become “satellite services” instead of “wire services.” AP and UPI envision a small fibre glass dish ground station on the roof of every daily newspaper in the country receiving the “wires” from a satellite in synchronous orbit. Harris has contracts with four of the eight foreign governments who have committed themselves to establishing satellite communications systems.

Harris also sold $60 million worth of newspaper “front end” and composition systems last year. Judging by the size and splendor of their Anaheim exhibit, the company is serious about projections that show the newspaper systems market growing by 20 to 30 percent over the next few years.

All this and more led Business Week to hail Harris as “masters of technological transfer” for their ability to turn government funded research to commercial purposes. Two third of the company’s $73 million research and development costs last year were paid for by government and large commercial customers.

This is fine for Harris and its customer’s who benefit from spin-off technology. The newspaper industry, in particular, has reaped enormous savings as a direct result. Nor is Harris the only company in this game of turn around from government funded research. For example, according to the authoritative Seybold Report. Raytheon’s new ad composition terminal was derived from air traffic control and monitoring systems built for the Federal Aviation Administration.

The government gets the custom hardware, the company gets the germ of a potentially profitable product and the industrial customer gets another valuable tool.

The taxpayer provides the ante. Which is great for the technology brokers and the newspaper industry but raises some questions about what American taxpayers are getting for their money.

Depending on how you look at it, spin-off benefit is yet another coil in the military-industrial complex or a shining example of what the American economy does best. Allan M. Siegal of the New York Times made no bones about the connection between government research and the wonders on sale in Anaheim. “This industry is healthy because of this trickle down from government funded research”, he said. The New York Times which signed an initial $3.5 million contract with Harris for a customized “front end” system (and has great plans for refinements yet unborn) is a beneficiary. No matter who pays for the basic research, Siegal believes that the generally bullish tone of the ANPA/RI conference is a direct result of this massive technological transfusion.

Without it, the scene in Anaheim would be markedly different. For one thing, Siegal who was an Associate Managing Editor (before his promotion to News Editor in July) won’t be at a “production management conference.” Only in the last five years have editors found these meetings “compelling,” according to Siegal. In that time, the responsibility for production has shifted from the composing room to the newsroom. The exhibits at Anaheim are crowded with editors and reporters because they, not the old-time composing room inhabitants, are the intended customers of much of this “production” equipment.

When editors like Siegal first began turning up at production conferences, they were all but overwhelmed by the profusion of rival companies and systems. Now editors are more knowledgeable about their own wants and the limits of technology. The technology companies, acting in close alliance with their customers, have institutionalized innovation so part of the compulsion for editors at these meetings is to spot new technologies and assess their possibilities. Living with a continuous revolution requires a new type of’ newspaperman and Siegal is a fine example of the new breed — what he calls “a newsroom ambassador to technology.”

Siegal found himself in that diplomatic role because he happened to be in the right place at the right time when the new technology “gave me the chance to break out of’ my little corner of the newsroom.” Siegal came to the Times as a copy boy during his undergraduate days at NYU. In 1962, he was hired as a copy editor on the Soc-Obit desk and a year later he was moved to the Foreign Desk. in 1966, Siegal left the Times to try his hand in television with ABC-News. He didn’t like TV and was back at the Times as Assistant Foreign News Editor a year later. In 1971, he was part of the super hush-hush team that edited the Pentagon Papers and won a Pulitzer for the Times. He was also assigned in 1970 to the Times’ cold type conversion project which seven years later is only just coming into effect. Unlike many editors who prided themselves on their ignorance about what happened to their copy once it went into the pneumatic tubes to the composing room, Siegal always had an interest in things typographical. In junior high, printing shop sparked his interest in good printing and handsome type. In the fourth floor composing room of’ the Times, he got along with the ITU printers, a highly individualized group of’ men and women including linotypists and doctorates and printers who taught college level English in their spare time. Those printers and their New York Typographical Union Local 6 were the chief obstacle to the Times’ entry into the new age. While management and labor fought the fateful automation battle, Siegal was undergoing an education in the arts of the electronic newspaper.

The delay in converting to cold type made the New York Times delegation to production conferences perennial wallflowers. It also let other newspapers make the costly mistakes inherent in buying first generation technology. It was the historic 1974 ITU contract that conceded the right of unlimited automation to management that finally led the Times onto the dance-floor of the new technology. Today, the “good gray Times” still cuts a cautious figure out there. A newspaper the size of the Times has to ease into a new technology in careful stages. Perhaps because of the years observing the others, Siegal casts a cool eye on the proceedings at Anaheim. Perched on a table in the lobby of the convention center, Siegal said that the, big excitement at these meetings in the years following the introduction of computer systems into the editorial department has died down. With a sweep of his arm, Siegal declared. “This has ceased to be compelling. Most papers know which way they are going now.”

The technological revolution hasn’t stopped, Siegal believes. “It will never reach a stable state but it’s not accelerating at the moment. Last year, I arrived in Las Vegas expecting to see a pagination breakthrough and was disappointed. ‘This year, I came not expecting to see a pagination system and wasn’t disappointed.” The reasons are many, according to Siegal. First the industry has to digest the vast amount of equipment it has swallowed in the past five years. Photocomposition and front end systems required large capital investments and many papers want to savor some of’ the cost savings in reduced labor before rushing into something else.

It’s cost efficient to replace a highly skilled and paid printer working at a cumbersome linotype with a semi-skilled typists pist ‘”inputting” on a VDT. The cost problem for editorial pagination, Siegal explained, is that it replaces a semi-skilled paste-up artist wielding an Xacto knife with a well-paid editor sitting at the controls of a highly complex and expensive computer system. Xacto knives are still a lot cheaper. The cost savings are just not as great, according to Siegal.

Advertising make-up is the area where pagination is making the greatest progress. Siegal pointed to the number of companies at Anaheim such as Raytheon and Camex promoting new ad composition terminals. The Boston Globe which is using the Camex ad composition terminals has been talking editorial pagination for a while but Siegal said, “You can bet that if the Boston Globe were champing at the bit, they would have a pagination system.

Yet Siegal believes that as more newspapers become completely computerized, the potential cost savings will provide the lure for a practical interactive editorial pagination system. Full pagination leads, the way to the next level of technological sophistication. First will come pagination without graphics, Siegal predicted. Editors will lay out and compose their pages on big screen terminals. Stories, headlines and captions will be generated and manipulated on the screens until the page is complete. As electronic graphics improve, the systems will display digitalized pictures in their proper size and position. Once that is possible, papers will be able to skip the current plate-making process. Instead, the electronically made-up page will be beamed directly to a new type of’ plateless printing press that can change images while running. These presses need not be located in a massive central printing house but can be installed in much smaller plants close to the readers they serve. Pagination will allow more specific zoning, that is, special editions of the newspaper pitched to small geographic areas. The New York Times which in recent years has sprouted new zone sections aimed at the boroughs and suburbs could refine the zones even further so that small advertisers could use the Times to reach their local customers. With computers keeping track of these local ads and editors at pagination terminals making quick adjustments between a hypothetical East Orange and a hypothetical West Orange New York Times, the presses could be instructed to knock out just the right number of each edition.

Yet Siegal believes that as more newspapers become completely computerized, the potential cost savings will provide the lure for a practical interactive editorial pagination system. Full pagination leads, the way to the next level of technological sophistication. First will come pagination without graphics, Siegal predicted. Editors will lay out and compose their pages on big screen terminals. Stories, headlines and captions will be generated and manipulated on the screens until the page is complete. As electronic graphics improve, the systems will display digitalized pictures in their proper size and position. Once that is possible, papers will be able to skip the current plate-making process. Instead, the electronically made-up page will be beamed directly to a new type of’ plateless printing press that can change images while running. These presses need not be located in a massive central printing house but can be installed in much smaller plants close to the readers they serve. Pagination will allow more specific zoning, that is, special editions of the newspaper pitched to small geographic areas. The New York Times which in recent years has sprouted new zone sections aimed at the boroughs and suburbs could refine the zones even further so that small advertisers could use the Times to reach their local customers. With computers keeping track of these local ads and editors at pagination terminals making quick adjustments between a hypothetical East Orange and a hypothetical West Orange New York Times, the presses could be instructed to knock out just the right number of each edition.

A newspaper written, edited and assembled on a screen could also be delivered to a screen. That raises exciting possibilities for newspaper publishers and frightening ones as well. On the plus side, Siegal sees fully made-up pages of the New York Times being sold to newspapers both here and abroad in much the same way that the New York Times News Service sells individual stories today. Client Papers would receive the press-ready pages electronically via satellite.

An electronic page could also be sent direct to home television, using the new “frame-grabber” technology, according to Siegal. The British Broadcasting Corporation already produces a simple “tele-text” magazine for English subscribers under the name of Ceefax. The “magazine” is encoded onto empty lines in the television broadcast signal by a computer that “dumps” its entire data base over and over at high speeds. The subscriber has a small keypad on his home set that calls out the “chapter” and “page” that he wants. Within 16 seconds, the requested page comes round on the circulating data base and the home decoder grabs the frame to display it on the screen. Thus the subscriber can call out the European ski conditions which will stay on the screen as long as it is wanted. The page is updated as revised information is entered in the Ceefax computer.

The New York Times financial section subscribes to a similar system marketed by Reuters in the United States. The Reuters Monitor carries the latest information on securities, commodities, money rates, market reports, quotations and news headlines. A keyboard “turns” to the page with the desired information and the system is also programmed to watch for unusual movements in the prices of key stocks. The Monitor is responsible for some further technological displacement. “We used to have two people who watched the tape for this activity but now we moved them elsewhere,” said Siegal.

The Monitor is a pricy service for customers with specialized information needs. Reuters is doing well with a racing “wire,” giving serious students of the turf the latest updates on odds, scratches and form. Reuters is also aggressively marketing a home viewer information service to cable television companies. Already on Long Island, 60.000 homes get the Reuters News-view package of’ news and features plus a custom local news service collected by the cable company. Besides the latest news and sports, customers can use their TV’s to see weekly supermarket price comparisons, how late the Long Island Railroad is running and who is getting married in their town.

These are all one-way systems with a central data base being pumped to subscribers. A two-way interactive system between a subscriber and a newspaper offers even more options, according to Siegal. Instead of merely choosing from a selected flow of information, a home subscriber to a two-way system could access himself to the whole data base of a newspaper including the current news and the back files. The New York Times Information Bank has 200 customers for a simple index search system that draws on its morgue from 1969 on and 70 other publications from 1972 on. On phone lines, subscribers call in on their terminals to specify the information they want and the paper sends back a printout of references.

Computerized morgues or electronic information retrieval systems to call them by their full name were very much in evidence in Anaheim. Mead Technology demonstrated the library system it created for the Boston Globe. Instead of indexing the library by categories, the Mead system keeps track of every word that appears in the paper. The user asks the system for any entry in which the words, say “Carl Yastremski,” “Yankees” and “home runs” appear together. The screen tells the user how many entries contain those three references and then on Command displays the actual articles with the reference words blinking in red.

Siegal believes that two-way systems could be adapted to allow home subscribers to shop via computer. After reading the ads in the morning papers, customers could call the newspaper’s computer, keyboard in their orders which would be relayed to the retailer. The newspaper could become a merchandise clearing house and take a commission on sales.

The limitations are not so much in the technology, Siegal contends, as in the basic business strategy decisions behind it. “It’s not possible now to sit at home and ask your TV set for a page of the New York Times. All these things are close within the grasp of today’s technology but they are not within the grasp of today’s commercial thinking,” he said. “Too many options undercut the commercial underpinning. For example, if you could buy the New York Times in pieces, it would destroy our ad base.”

All this frantic modernization is being fueled by the cost savings gained by automation. As Siegal put it, “It’s cheaper for machines to do things than for people to do them.” It costs the New York Times $27,000 a year plus fringe benefits to employ air ITU printer, according to Siegal. That arithmetic can sustain requests for very high priced systems as long as they displace even higher priced humans.

The New York newspaper union situation is a vast muddy field churned into a treacherous swamp by years of bad feelings, heated words, angry denunciations and not a few strikes. Before venturing into that morass, Siegal was eager to make it clear that his was a minor role in the complex struggle between Times management and union officials. Following two intensely bitter and costly strikes in the early 1960s, the Times was hit by a series of extended chapel meetings by Local 6. The “typos ” were spending up to 19 hours in a three shift day in composing room chapel meetings. Day after day, the Times was dragged to the brink of missing publication as the chapel meetings adjourned with barely enough time left to put out a skinny paper. The resulting 1970 contract (gave the unions a 41.7 percent wage increase. When publisher Arthur Ochs “Punch” Sulzberger totted up the wasted labor costs, the lost ad revenues and the cost of the wage increases, he resolved in the 1973-74 round of talks to break the ITU’s power at all costs. As Siegal understood it, “We would do what it took to remove the ITU’s veto over automation.”

A war chest was set up and the Times created a “secret” advanced technology room on the 11th floor. The secret was rapidly no secret to the ITU but the Times was more interested in demonstrating that in the event of another strike, the paper had the capability to publish with or without union printers. The building of a large offset satellite plant in Carlsbad, New Jersey, was another signal to the printers that Sulzberger meant to fight the next strike to the death.

That final battle was avoided. After a whirling round of negotiations and psychological warfare, the Times signed in 1974 an historic 11-year contract with the ITU that supposedly has settled the technology question forever. The ITU conceded the unlimited right to automate the composing room to the Times in return for lifetime guarantees of employment to all the full and part-time ITU members. Members who quit, die or retire will not be replaced. The ITU gave up its controversial “bogus” type rule, whereby any matter that came to the Times preset had to be reset in hot metal, proofed and then junked. The new agreement allowed the Times to use any kind of machine readable or scannable copy. Any straight copying over of copy was reserved to ITU members.

In essence, Siegal, “The ITU negotiated themselves out of existence but in conditions of dignity for the members.” Many older linotyptsts and makeup men were bought out with early retirement bonuses. The rest will be retrained and shifted to other positions as the cold type conversion moves forward. In the past, the ITU men would have nothing to do with any kind of new machine or innovation. Since the new agreement, Siegal said, their chief’ complaint is that they are not being retrained fast enough.

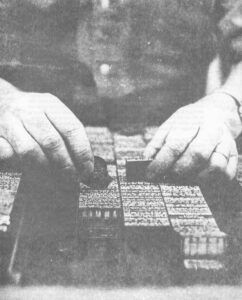

No matter what happens to the individual typographers, Siegal has little doubt that their trade will become extinct in the newspaper business. “In ten years, there wouldn’t be a recognizable composing room. There won’t be printers as such.”

Despite the length and bitterness of the struggle, Siegal said the ITU position was doomed. “After World War II maybe if they had had a crystal ball there might have been a few things” the ITU could have done to preserve their position. But with the coming of the VDT. “they could not have resisted any longer.” The future of the ITU as a union outside the newspaper industry will depend on increased flexibility, Siegal believes. “They’re not going to get the same rate for gum chewing teenagers who operate keyboards as they used to get for journeymen linotypists.”

But in the end, so many of the ITU members failed to see which way the winds of change were blowing. “I’ve seen the handwriting on the wall for 10 years. A lot of’ them didn’t see it until last August (when the first TTS tape produced by the editorial department was sent up to the Composing Room). A lot of them having seen that didn’t believe that editorial could produce photoready copy.” Now there are no doubts.

Is it correct to see the end of metal printing as the end of a craft? Siegal made a distinction, “There is a difference, between a trade as handling things on a daily basis versus artisanship. Machines will be, if they are not already, turning out furniture but there will always be a market for handmade furniture.” The transfer of a workaday trades to computer control is inevitable. “Metal printing will be done as a hobby in much the same way, as I imagine that the illumination of parchments is done as a hobby.”

Aside from the nostalgia, is there anything being lost in the computerized “new New York Times?” Siegal pondered the question, staring off into the middle distance, trying to give this a fair answer. Finally, he shook his head, “There’s none that I can think of.”

If technology has been kind to newspapers of late, it makes no promises to remain so. Many publishers who watched television decimate their readership thought that the cathode ray tube would be the death of them. Many were right. If the glowing screens are making amends to newspapers now, they are long overdue. But the machine giveth and the machine taketh away.

The future supposedly belongs to those who worry about it so on the last day of the production conference, ANPA/RI threw its annual crystal ball session for the assembled newspapermen. “Dateline 90” was not merely a presentation but an event. The show opened with a battery of projectors backed by a high fidelity music track bombarding the audience, with a kaleidoscopic summation of the advance of technology. Slides of’ hand presses, telegraph keys, carousel horses, deskmen in green eyeshades, linotypists in bowler hats cascaded onto the screen; the soundtrack played colonial fife and drum marches, piano rags, the Andrews Sisters warning “Don’t Sit Under the Apple Tree.” The Beatles took the slides into the present of lasers and microelectronic chips.

As the multi-media light show lifted, the Research Institute speakers moved into a carefully scripted presentation. Frank Romano who is the president of the RI Production Department told the 10,000 sitting in darkness before him that they were all on a time trip in the 1990s where space shuttles routinely drop communications satellites into orbit, where fibreoptics and bubble chips have made computer memory storage and transmission dirt cheap.

And there will be newspapers in the 90s, said William D. Rinehart, an RI vice president who popped up across the stage at another spotlit lectern. Newspaper will remain the dominant information and advertising medium, he said. There will be direct satellite communications to every newspaper in the country, relaying not only news from the rechristened AP and UPI “satellite” news services but also ads beamed in facsimile from national advertisers eager to use this low cost next day network. The light weight presses of the 90s with vastly improved color capability will be deployed in small zone plants all over a newspaper’s circulation area and receive high speed facsimile pages direct from the central editorial office over low cost fibreoptic transmissions lines. Photographers will use all-electronic news cameras to send pictures back to the office electronically where they will be digitalized for use in the editorial system.

The climbing cost of paper will be the biggest threat to the printed and delivered newspaper, according to Edwin Jaffe who directs the RI Research Center. By the 1990s, the paper making process will be totally overhauled and the present pulp slush method invented in France in 1798 will join hot lead technology in obsolescence. The papermaking plant of the 1990s will employ an ecologically approved dry process on a new source of pulp, extracted not from trees but from new cultivated varieties of grasses and bushes. The leading candidate is a shrub called kenaf. With a dramatic flourish, Jaffe whipped a black silk cover from a drum in front of the lectern to reveal the very first roll of paper ever made from kenaf. The spotlights glittered off the white paper as Jaffe sang its praises. Kenaf (hibiscus cannabis i.e. the hemp-leaved hibiscus) is an annual plant that can be grown in nearly every climate zone in the United States. Kenaf can produce four tons of pulp per acre every year versus three quarters of a ton for softwoods. Today’s dirty north woods paper plants will decline as the cleaner and closer to market kenaf plants are developed.

The new newsprint will be off higher quality to show off the improved color capabilities of the 1990s presses, Jaffe continued. The presses will be lighter, faster and virtually automatic. Jaffe prophesied the demise of today’s l9th Century-designed 100 ton monster that requires a city block and a squad of skilled pressmen to put one-fifth of’ an ounce of ink on a 64-page paper. Within five to seven years, the new compact designs will print from plastic plates with far fewer rollers, lighter gearing and small energy-efficient motors. Ink jet and laser plateless presses guided by low-cost computer memories will have the capacity of changing the contents of every newspaper as it is printed, Jaffe said.

The wild card in this game of media fortune telling, according to Richard Palmer who is the Director of News and Production for the Baton Rouge Morning Advocate and State Times, is the electronic information system. Palmer told of his experiences in England where he had a good look at the BBC Ceefax System. While Ceefax is still relatively crude, Palmer said the technology has extremely seductive features. It allows the viewer, by controlling the pace and selection of information, to create his own special interest magazine. “It combines the immediacy of’ TV and radio with the relative permanence of’ newspapers.”

Oddly enough for a member in good standing of an industry that has prospered because of spin-off benefit from government research, Palmer felt that government involvement in tele-text research made it all that more sinister. “Tele-text systems as they exist today are products of governmental agencies which depend for their very existence upon public grants rather than advertising revenues. And it may, in fact, be tele-text which puts the United States government into the full-time news business in competition with us as well as the broadcast media for the time and attention of the public. BBC has already suggested to a receptive FCC that the Public Broadcasting System become the vehicle for the use of this new medium here. Can’t you imagine the lead-in to the news show: ‘Here is the news your government wants you to hear.’ Although It is hard to envision public television as a full-fledged threat to the daily newspaper industry, it is not hard to see that it could add another source of’ news for the consumer. And we do not fully know what his saturation point is or may become.”

There is no reason to panic, Palmer assured his audience of print venders, “A lot of this is going our way.” A viewer who is “reading” his TV is not watching the regular programming. A tele-text” information service would further fractionate the TV audience. Already “pong” type screen games and videotape players are competing for screen time with “Charlie’s Angels.” Tele-text systems could be a plague on the house of broadcasting, cutting the number of heads to be sold to advertisers and driving the remaining prime time audience median further downscale in intelligence and income. Tele-text would, after all, be a text and those who read their information off’ the screen still prefer written tangible confirmation. They also need more detailed in-depth coverage, according to Palmer.

So newspapers would be silly to close their eyes to this new electronic Information medium, hoping it will go away, says Don Wright who is the executive editor of the Minneapolis Star. Newspapers are in potentially lucrative positions to cash in on it, said Wright. If a tele-text system needs news text, who is in a better position to sell news texts than newspapers? More importantly, newspapers have gained so much from the new technology of late, they would be foolish to reject this new promise. After all, Wright pointed out, “We’ve shaken off a technology that first supported us and then constrained us.” Who knows what this gift horse has in the way of teeth?

All this heady stuff went down extremely well with his audience. The applause was warm and prolonged as Wright introduced special exhibits erected inside the main hall by a select group of companies whose advanced research projects are considered highly promising by the Research Institute. As the spotlight picked up their nervous salesmen standing by their booths, Wright read the roll of advanced technology. “Would you please join me, in welcoming AT&T?” And the 10,000 newspapermen gave AT&T a thunderous ovation.

When the lights finally came on at Dateline 90, a jostling crowd formed at the base of the stage as Erwin Jaffe reeled off’ free samples of’ the wondrous kenaf paper. The men grabbed and tugged at the sheets, eager to tear off a piece of the shiny newsprint as tangible reassurance that technology led them into the promised land and will not desert them now. The newspapermen came blinking out of Dateline 90, clutching their kenaf paper as proof of that covenant. A visitor who wandered down to the exhibit hall for one last look found the caravan of newspaper technology had folded its tents in the night and moved on. Workmen struggled to crate up the last of the partitions and booths to make way for the next event. The visitor took his scrap of kenaf and went home to tell the world what he had seen.

The text was set on an IBM Selectric Composer in Bodoni Medium by Mrs. Hazel Richmond at the Department of’ Journalism, University of California, Los Angeles.

Received in New York on December 1, 1977.

©1977 John W. Fleischman

John W. Fleischman is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from Human Behavior Magazine. His fellowship subject is “The Medium of Print: A Craft Becomes a Computer Function.” This article may be published with credit to Mr. Fleischman as a Fellow of the Alicia Patterson Foundation and to Human Behavior Magazine. The views expressed by the author in this newsletter are not necessarily the views of the Foundation.