On a Wednesday afternoon last August. the beast of technology came slouching down Highway 68 through the heart of Yellow Springs, a small college town in southwest Ohio, and carried away a bit of what made Yellow Springs a little different from other places. There was no blood spilled, only ink. The Yellow Springs News went offset.

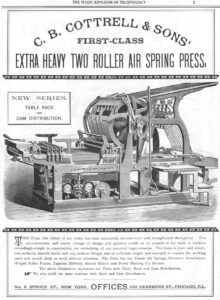

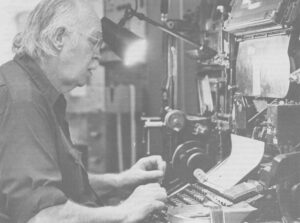

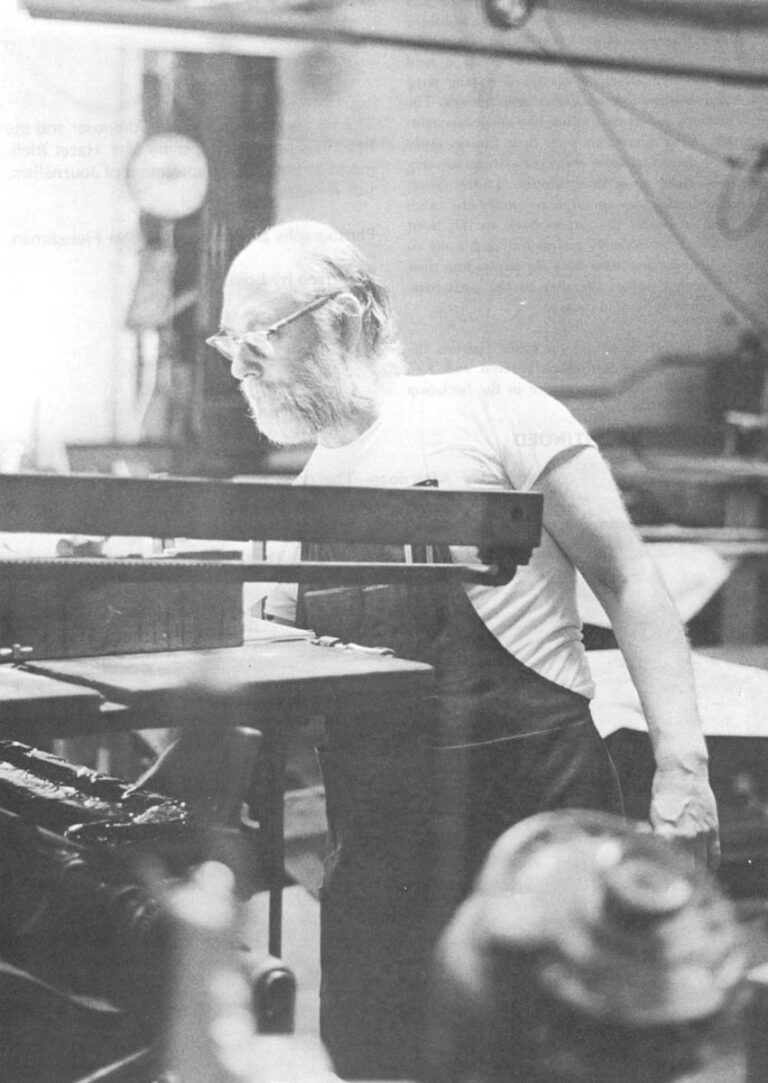

A generation of machines retired from the business of printing the weekly newspaper. The immediate victim was the News’ venerable Miehle, flatbed cylinder press, manufactured around 1906 which the News bought in 1960. The Miehle is not worn out-far from it. Because machines were made to higher standards of longevity in 1906 than they are today and because the people at the Yellow Springs News have lavished oil and grease on its every moving part, the big Miehle is in fine shape. Ken Champney, who is the publisher, one-third owner, chief printer and managing editor of the News, has nursed it all this time and says the Miehle is good for another 70 years of service.

The Miehle prints by a process known letterpress from forms made up of hundreds of lead slugs that carry the image on raised metal surfaces. The slugs are cast by the News’ assorted collection of Linotypes, wonderfully sophisticated and ingenious machines invented around 1880 by a German mechanic named Ottmar Mergenthaler. On the hundredth anniversary of Mergenthaler’s birth in 1954, the Mergenthaler Linotype Company proclaimed that it had sold over 70,000 Linotypes in this country and another 28,000 in Europe. The Linotype and its rival, the Intertype, were then at the height of their influence, the work horses of the printing industry, the undisputed kings of the composing rooms, the coiners of nearly every word in the public print. Yet within a decade, the Linotype’s position was seriously undermined by computer-driven photo compositors that turned out their type on paper that was pasted down. photographed onto plates and printed on offset presses. Ten years offset presses. Ten years further on, the Linotype is on its way to oblivion. In the summer of 1977, there were but a handful of American newspapers that used Linotypes. And now in Yellow Springs, there was one less hot lead newspaper.

The old machines weren’t to be Junked. The News hopes to continue a good business in job work setting and printing college newspapers. The college papers used to be the bread and butter of the News. That work has dropped off drastically as many student papers leased their own photo composers and went offset but the few papers that remain with the News have their own reasons for staying. So the Linotypes and the Miehle will probably march on into the 1980s running off college papers and job work but they were retired from their primary task of printing the weekly News. Ken picked up a secondhand photo composer that runs on punch tape. He had paste-up easels built and laid in a supply of wax, stick-on rules and tape borders. The News, which cannot afford the enormous capital expense of buying an offset press unit with its attendant cameras and platemakers, is jobbing out the printing of the paper’s press run to a plant in Urbana 30 miles to the north.

In the great scale of events, the fate of the Yellow Springs News seems small potatoes indeed. A 2,000 circulation weekly is switching machines. Our great cities go bankrupt, war and peace play their usual game of tag, grave crises of every kind are solemnly thrust down our throats. Americans this year are even supposed to be worried about the Panama Canal. The national debt goes on abuilding. The national ruin continues likely. Yet here in this small event-this mote in the bleary eye of history — can be read the invisible hand of time propelling us from one age to the next, from one way of work to another.

Consider: why is a way of doing something practical one day and obsolete the next? Why were the railroads the great sinews of one America and the great burdens of our time? Why aren’t the ceilings of automobiles sewn cloth instead of stamped cardboard? Why has the roadside burger served on a china plate become a thinner patty on fatter bread wrapped in two and a half yards of paper products?

Why is it possible to print the Yellow Springs News by letterpress one week and the next it is necessary to drive 30 miles to run it by offset in somebody else’s plant?

These are almost foolish questions best turned aside with clichés. You can’t hold back progress. Times change. Resources are getting scarcer and more expensive. Technology has moved on. Inflation is eating up everything. Labor costs are going through the roof. But up close during the last two weeks of the letterpress News, it did not turn out to be a simple question.

For one thing, Ken Champney was not even expecting to save money by going offset. He figures the savings in ad and page make-up which are immediate advantages in converting will be wiped out by the new printing bill from Urbana. “If six months on, it is costing us the same amount of money to print, I’ll be well pleased,” Ken says.

Ken says it’s a question of people. “For other reasons. we’re having, a high staff turnover. Keith Howard, who was the editor for over 30 years retired last year and soon after, the News lost its other reporter, Eleanor Switzer. Two of its skilled printers, Zeb Taylor and Lynton Appleberry, only work part-time now to supplement their Social Security. Parts for the Linotypes are getting more and more costly. The few suppliers left in the business are requiring larger minimal orders and giving slower service. The cost of sheet cut newsprint is beyond ridiculous.

But there was also a moral dimension to the events of this summer at the News. After all, the News had gone on with hot lead long past the time when the common wisdom in the trade was to convert. Some of that persistence was due to economic facts. Even now, the News is not so much converting to offset as patching their operation into the process. The News has no capital reserves from which to draw gleaming offset presses and sophisticated camera rooms. Hot lead printing is also something Ken Champney understands and this cold type thing is a step into the dark. As Ken put it, “if you know how to do something, you don’t want to go out and do something else.”

There is also a feeling of having been pushed into a corner by events that are not to the liking of the people at the News, that this new technology is part of the American ethic that the News has always resisted-big money, big machines, with people last of all. Hot lead printing was the ideal process for the product of a weekly newspaper. Its principles are within the budget, the comprehension arid the skills of men like Ken Champney. There is very little that can go wrong with a Linotype that the manuals, time and Ken Champney cannot puzzle out. It is also sustained by labor not capital.

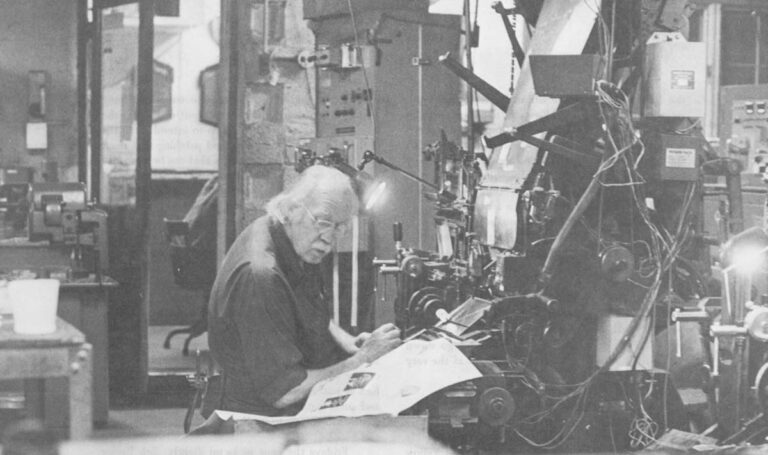

There are other implications that unsettle Ken. For the first time in its history, the Yellow Springs News will not be printed in Yellow Springs. Further, it puts the quality of the printing in the control of others. While the Miehle was running the News, Ken was never far from the receiving end, squinting at the sheets as they came off and fiddling with the screws that control the ink trough to insure that the type comes out jet black and the impression is sharp and clean. Over the years, the News won a number of state and national awards for its appearance including one competition where the judge complimented Ken on the “fine offset presswork.” Soon the News will be Just another short run job for a big web press in Urbana. As much as Ken rationalizes the decision, the thought galls him. “I’ve been talking to other publishers on how to lean on printers,” he says hopefully. Until now, there has never been a split between Ken Champney, publisher and Ken Champney, printer. In his own shop, Ken could fuss to heart’s content (and his stomach’s pain). In Urbana, he will be just another customer hanging around someone else’s pressroom grumbling. That doesn’t go down well with a man to whom self-reliance is at the very heart of his being.

Every periodical has its rhythm and a weekly newspaper turns around once a week. The Yellow Springs News comes out in a mad rush Wednesday afternoons. Thursdays in the backshop have the feel of a morning after. In the days when the News printed more college papers, the shop would be hard at it Thursdays and Fridays and even sometimes into Saturdays until the last college editor grabbed his papers for the run back to Wilmington or Cedarville. But a lot of that work has fallen off of late and the summertime is always slow with colleges.

So Thursday is a good time for Ken Champney to run the Elrod. The Elrod is a slug extruding machine, a squat affair about four feet long set on its own bench so it comes up to a man’s waist. It goes kachunk, kachunk all Thursday long, sounding not unlike a cat trying to cough up a hairball. The Elrod is essentially a little pool of molten lead that is continually being pumped through a die cooled by running water. The emerging bar of lead is drawn by an automatic set of jaws into an endless ribbon. When the lead gets to the end of the tray, a chopper automatically slices it off and a track carries the piece away to make room for the next section that is already pushing its way out of the jaws. The Elrod casts the slugs and leads that surround the type and picture blocks. The News goes through a lot of lead in a week.

Most of the time, the Elrod sees to itself. Every so often, it buzzes for a human to come and hang another pig of lead in the melting pot or to clear the tray of product. This allows Ken to attend to all the duties of cleaning, adjusting and patching that must be done and all the maintenance that can be squeezed in. Every so often, the Elrod stops and Ken drops what he is doing to go at it with vise grip pliers and screwdriver. Sometimes it’s something obvious — a dirty plunger or a blocked oil drain. Today, it is something mysterious. Ken goes through all the routine steps that check out each of the Elrod’s major assemblies. Eventually he reaches a critical mass of’ adjustments and cleanings so that when he switches it back on, the Elrod resumes its normal coughing. The shiny bluish slug emerges, grows to its predetermined length, is chopped clean and shunted away. Apparently the Elrod has had enough attention and Ken walks away rubbing his hands thoughtfully on an orange wiping rag. The machine is running again but Ken is not entirely sure which of his various tricks and cures worked the trick. The Elrod prefers to keep some of its secrets to itself.

Fridays the pace picks up slightly. Zeb Taylor comes in to set type for the Antioch Bookplate orders. The Bookplate, as it is always called, is the News’ biggest jobbing account supplying the business that will keep the Linotypes going for a few years yet. A bookplate is a full-color gummed label pasted in the front of cherished volumes to mark the owner as an individual with taste and a desire to see loaned books home again. The Bookplate runs off thousands at a time on its offset press on the other side of the village. When a customer wants his name to be printed on a hundred or so, the News does the typesetting. The work keeps Zeb busy and the Linotype Pots lit.

Dot Thomas who spent Thursday breaking up ads and refilling the slug racks is now setting advance ad copy. She moves from one Linotype to the next to collect all the various type styles and sizes that ad work requires. After three o’clock, a high school kid gathers all the hell boxes from around the shop and fires up the smelter to cast new pigs of lead.

Fridays, Ken is in his little cubby hole office behind the Model 32, running over accounts and bills, ordering supplies and trying to think of an idea for his weekly column, “Champing at the Bit.” This week Ken is riding a favorite hobby horse-the village water tower which imploded during the ferocious winter of’ recent memory. Apparently the federal government has given the village a $250,000 grant to build a new tower but since insurance and state funds will repair the old one, the feds are paying for a second tower. Ken wonders if the village needs a second tower, given the usually low casualty rate among water towers. It’s all right for locals to sound off about narrow local interests wasting tax money by demanding the building of B-1 bombers so engine factories in Cincinnati will be busy but here is a local case of tax money being spent because it’s there to be spent. It’s a fine, example of the Champney political perspective. The column is certain to set teeth grinding over at the village offices.

Monday mornings, the Little League results are in. Weddings, senior citizen outings and the church news are waiting in the copy basket for a free machine and a free operator. Dot is making up ads and setting late ad copy. Ken is hard at his column between interruptions to adjust the temperature of a lead pot or change a heavy magazine for Dot. Ken is also the chief darkroom technician and Don Wallis, the editor of the News and its chief photographer, has already left a few rolls to process. Late in the afternoon a barn goes up in flames on Polecat Road and Don comes back with a roll of great pictures chuckling to himself about the headline he will write “Barnburner.”

Tuesday, there is a visible acceleration. The Linotypes start up at 8 a.m. Don presides over the editorial office which is about 50 square feet of paper, beat-up furniture and well worn typewriters. Lynton Appleberry turns up to chat awhile before starting in on the classifieds. By mid afternoon, three Linotypes are running. Tracy Logan is cleaning the make-up stones before starting to lay down type. The layout of the inside pages is left to his sense of design and the precedents of history.

Late in the afternoon, the frenzy in the newsreel peaks. Contributors dash in with reviews and columns. Mark Bernstein, who covers the board of education part-time, is agonizing over his copy. Don sits in the back frowning at the editorial in his typewriter. Page dummies are screaming for his attention. Julie Monroe is dashing in and out with ad proofs. Late pleaders call in to see how elastic deadlines are today.

There’s a lull around suppertime. Dot punches out to go home and some of the others go to eat but Lynton holds the pace at his machine. By six, all five Linotypes are running again. The long galley trays which seemed to fill so slowly through the day are flooded by story after story. Over in Ken’s corner, the photo lathes whine, the cylinders turning under electric cutters. Ken’s son, Carl, who runs the office, writes sports and keeps tenuous charge of the paper carriers, is correcting galley proofs. His mother, Peg, has been setting type all day.

The backshop is an orchestra of machinery — the tinkle of falling brass mats, the thump of casters, the shrilling of engravers, the harsh buzz of tablesaws. By nine in the evening, the Linotypes are running flat out. The pressure is on to get the first four pages ready for a morning press run. Peg and Lynton clear the last of the copy by just past eleven. Don brings back the last dummies to the stones where Ken and Tracy are building the forms. As the Linotypes stop, the pace slackens but the tedious work of setting corrections and grabbing the final bits and pieces to close continues. Ken works until one in the morning if all goes well. Things have a habit of going wrong and when they do, Ken works even later.

The last one out in the small hours of the morning, Ken is usually the first one back after sunrise on Wednesday. Yesterday’s quiet determination is replaced by a slightly giddy panic compounded by the shortness of the sleeping night, the looming deadline, the fear that something vital has been left out and something terrible has slipped in. Late copy is extracted from the editorial department.

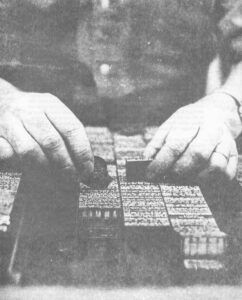

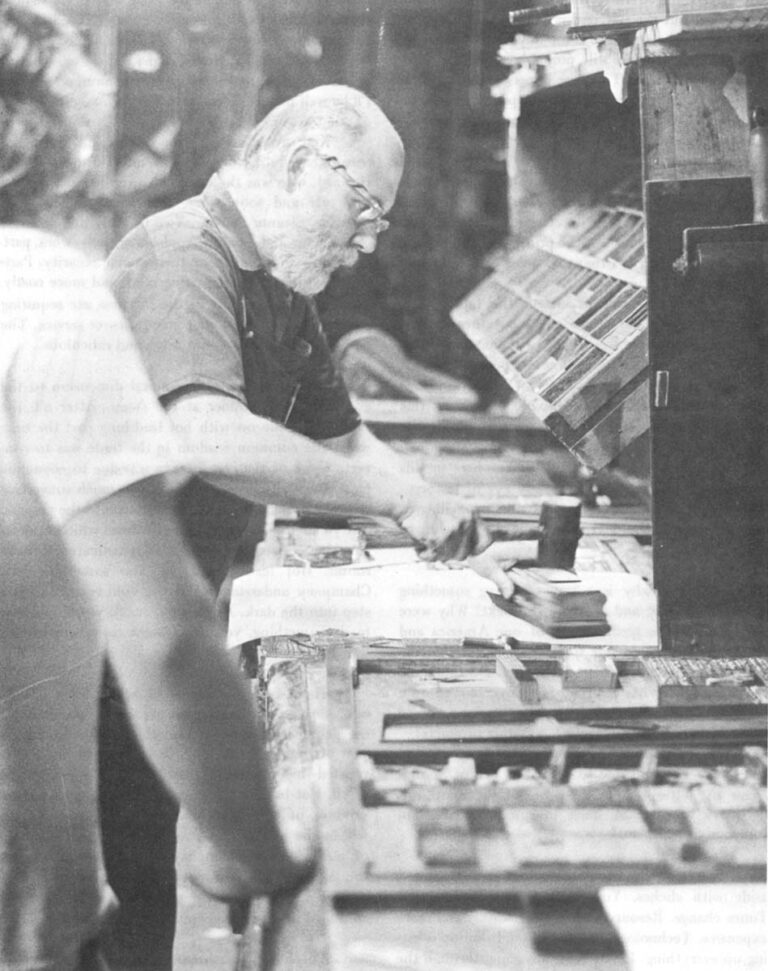

The big Michele has to be readied. Ken’s daughter Becky alternates the pressmen’s duties with another village teenager, Susi Van Gierke. Susi changes the tympan sheet, fills the ink trough and drags the paper cartons into place by the time the first run is press ready. Meanwhile Ken has slipped the last piece into the pages and inked them with a hand brayer. He places a sheet of newsprint on the surface and hammers at a wooden planer to produce a page proof. The last point where corrections can be made easily, the proof is carefully read by Carl and then given a final going over by Don. Corrections are made, and then Ken starts the nerve-wracking final lock. Wedges called quoins are tightened to hold the whole lead jigsaw puzzle together. Extra leads and paper slug-sinkers are slipped in to hold trouble spots. Then the whole steel chase is pryed up by the corner to rest on the quoin key. Ken drums up the type with his fingertips to test if anything will drop free.

A page that is not tight will “work up” on the press or, worse, actually throw a line out to wreak havoc on its fellows. When the page finally locks, the chase is hoisted up on edge and the back is scraped with a make-up rule to get rid of any lead burrs that might raise the surface above the magic .918 inch which is type-high. Holding two full-sheet pages, the chase weighs well over a hundred pounds. Ken and Tracy take a deep breath before lifting it gently and carting it over to the press bed.

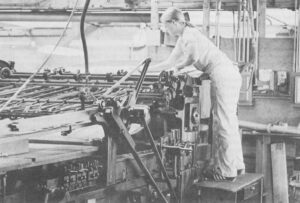

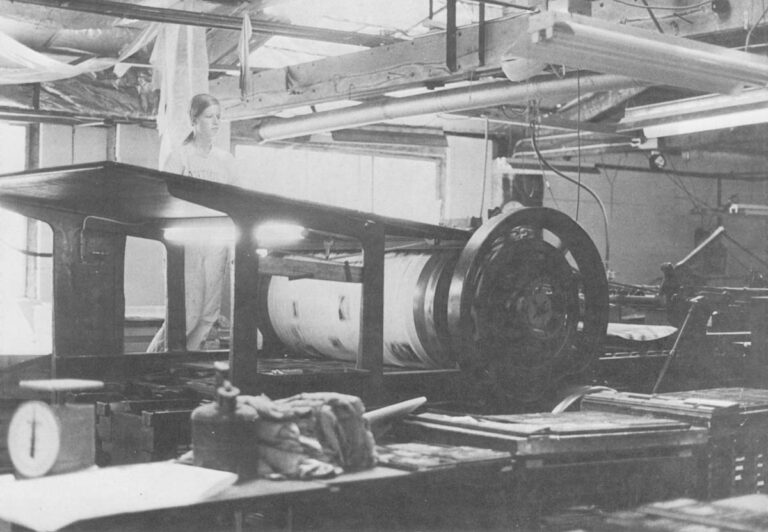

The Miehle is hand fed, one sheet at a time from a raised platform with the bed at the pressman’s feet. To lock the chase firmly into place, Ken all but climbs into the brightly lit cavern under the feedboard. He also sees that no keys, quoins, screwdrivers or extra slugs are left on the type. When Ken finally pulls his head out and double checks the gate that keeps the chases from flying backwards, Susi runs a few test sheets. The Miehle is a ponderous monster that starts up with a sharp bang as the electric motor kicks over the heavy cylinder and sends all the rods and rollers into their prescribed gyrations.

With an elegant wrist action, Susi flicks a sheet free from the stack and guides it along on the resulting air cushion into the grippers. The bed is inked by two sets of rollers turning against a massive moving ink plate. As the bed rushes forward, the great cylinder lifts to let it pass on to meet the sheet coming down and then descends on the returning bed to kiss the type against the paper with precisely calculated but immense force. The printed sheet is carried back over the top of the cylinder where it is pulled through a web of pulleys and wires to be seized by a row of mechanical fingers. The fingers draw the sheet over a bar of burning gas that bakes the ink into the paper filling the pressroom with the nutty smell of toasted newsprint. The fingers release the sheet into a self-squaring wooden receiving box where Ken stands, examining the sheets and adjusting the ink fountain. Once he is satisfied with the impression, Susi climbs down from the feedboard to increase the speed and then climbs back up to run 1100 copies. Then she shuts the press down to retrieve the printed sheets for a second pass on the back. The Miehle works with a stately roar and thump, all its gears, ratchets and rollers spinning like the innards of a fine watch.

In the office, Carl has just come back from the supermarket with the makings of the traditional Wednesday lunch. He stashes the perishables in the aged Philco refrigerator which has a screwdriver dangling by rubber bands from the handle and a series of little notices in various handwritings offering advice on how to use the screwdriver to close the door. Carl clears the rubble from a long table and lays a tablecloth of newsprint. Lunch today is cold cuts, cheese, two kinds of bread and mounds of vegetables including the cucumber overflow from the Champney family garden.

Gradually everyone but the pressman drifts in to eat. For about 30 minutes, the deadlines are forgotten as the staff munches and chats. As Ken prepares to polish off his sixth slice of cucumber. spread two inches deep with mayonnaise, Julie Munroe whose desk is covered by the food declares that the Wednesday lunches are becoming too much work. Carl says he doesn’t see the problem. The topic goes around the table. Tracy Lord says he empathizes with what he hears behind Julie’s complaint-that this is a man’s work-woman’s work issue. Carl doesn’t see that at all. He did the shopping. He does most of the cleanup and he doesn’t mind it. The issue is never resolved but the tone is pure Friends meeting.

But with the first run off the press, Ken rushes back to the stones to pull the remaining pages together. Now the race toward the three o’clock deadline gets grim. The press runs so slowly and the folder even slower that a ten minute setback on the stones will be magnified by press and folder into a half hour delay. The paper carriers will pile up in the front office, block the entrance with their bicycles and plague Carl with complaints about extra copies and back payments.

As each run is finished, the chases are carried back to the stones and covered by battered wooden boards. The next run is lugged to the press. By two thirty, only page one is open. Dot sets the last few dribbles of corrections and missing captions. Don is struggling to compensate for a wrongly dummied picture. It would take much too long to cut another engraving on the photo lathe so Don has to decide between some rather lavish white space or a longer caption. Don likes white space and long stories, a taste that stirs up far more comment among the readers than all this talk of going offset. Ken finally wraps the picture block securely into the page, inserts the last correction and locks the chase. The last chase is hoisted up, scraped and hauled to the press.

As soon as a dozen sheets are run through on both sides, they are dragged to the paper cutter and then to the antique folder that even Rube Goldberg would have dismissed as too complicated. The folder which like nearly everything at the News is held together by “temporary” C-clamps is a ping-pong table-sized contraption of knives and pulleys. The two operators nod at each other like musicians sight-reading a string quartet to keep their timing. Daily newspapers have expensive conveyor systems to carry the papers from press to mailroom. At the News, Carl walks back every so often to empty the catch box. Then he walks the papers back to the front counter where he solemnly counts out each route to the impatient carriers who stuff the papers into their bags and rocket out of the alley to the swift completion of their appointed rounds.

It is dinnertime before the folder finishes, the press is cleaned, the last chase covered and Ken Champney goes home. The silence in the backshop is enormous.

TO BE CONTINUED

The text was set on an IBM Composer and the headlines on a Varityper by Mrs. Hazel Richmond at the UCLA Department of Journalism, Los Angeles.

Photographs and layout by John Fleischman.

Proofread by Louis Watanabe.

©1977 John W. Fleischman

John W. Fleischman is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from Human Behavior Magazine. His fellowship subject is “The Medium of Print: A Craft Becomes a Computer Function.” This article may be published with credit to Mr. Fleischman as a Fellow of the Alicia Patterson Foundation and to Human Behavior Magazine. The views expressed by the author in this newsletter are not necessarily the views of the Foundation.