As a photographer and writer I have spent nearly 30 years crisscrossing the continental United States in search of unique and typical examples of roadside and Main Street architecture and design. In traveling over 100,000 miles in a long series of marathon automobile trips, I have taken some 100,000 photographs of about 15,000 older buildings, signs, storefronts, and other commercial and civic structures. My 2003 Alicia Patterson Foundation Fellowship is allowing me to hit the road again in a series of four research trips in several regions of the USA to revisit many places I have not seen for decades. My objectives in these journeys are threefold: to see how places have changed; to record what remains of this individualistic “mom-and-pop” tradition in American commerce and how places I have previously photographed have evolved; and to make a record of the new omnipresent business chains which have homogenized the environment of America. This first report shows some of what I found in my first trip through the Southwest in over 3000 miles in 17 days. The Lone Ranger rides again.

Food:

Highway Diner, Route 66, Winslow, AZ, ca. 1940s

©2003 John Margolies

Jolly Cone Drive-In Sign, old Route 99, Bakersfield, CA, ca. 1950s

©2003 John Margolies

Sonic Drive-In, Central Ave., old Route 66, Albuquerque, NM, ca. 1990s

©2003 John Margolies

Wienerschnitzel, Las Cruces, NM, ca. 1990s

©2003 John Margolies

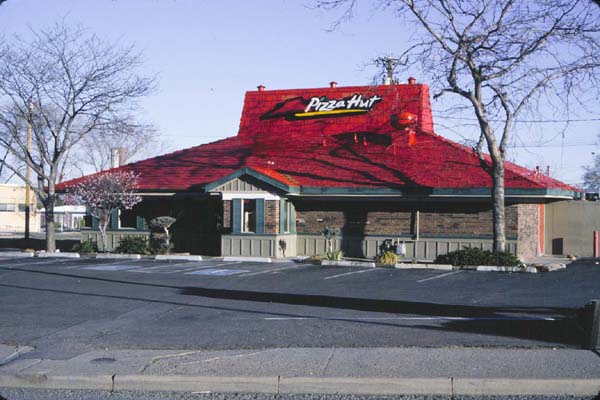

Pizza Hut, Cerrillos Road, Santa Fe, NM, ca. 1990s

©2003 John Margolies

Lodging

San Carlos Hotel, 1st and Main, Yuma, AZ., 1930

©2003 John Margolies

Cortez Motel Sign, Alameda Ave., El Paso, TX, ca. 1940s

©2003 John Margolies

Wigwam Village # 7, Foothill Blvd. (Route 66), Rialto, CA, 1953

©2003 John Margolies

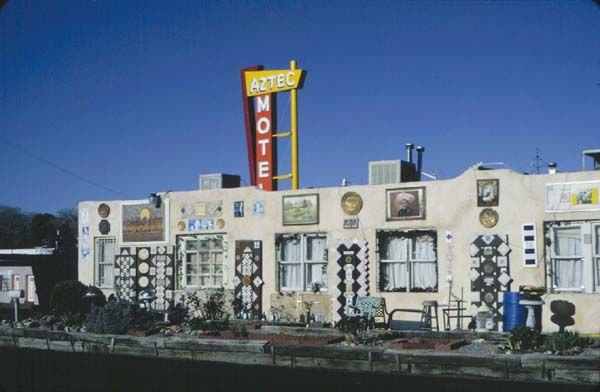

Aztec Motel, Central Ave., Albuquerque, NM, ca. 1950s

©2003 John Margolies

Super 8 Motel Sign, I-8 Business Route, Gila Bend, AZ, ca. 1990s

©2003 John Margolies

Movie Theaters:

Fox Theater Forecourt, 20th and C Streets, Bakersfield, CA, ca. 1920s

©2003 John Margolies

Balboa Theater, 4th and E Streets, San Diego, CA, ca. 1920s

©2003 John Margolies

Dream Catcher, Route 285, Española, NM, ca. 1990s

©2003 John Margolies

Pacific Gaslamp All Stadium 15 Theater,

5th Avenue and G. Street, San Diego, CA, ca. 1990s

©2003 John Margolies

Barber and Beauty Shops:

Shear Indulgence Beauty Salon, Winslow, AZ, ca. 1930s

©2003 John Margolies

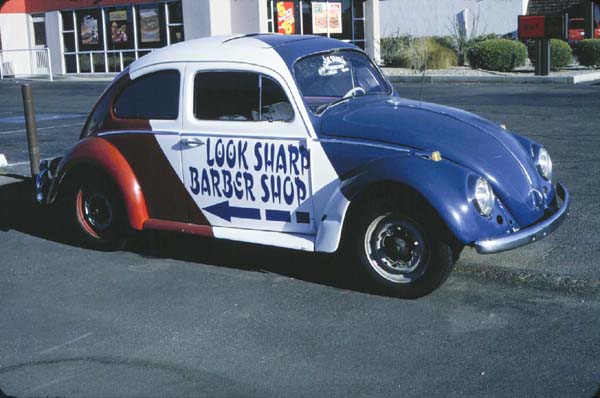

Look Sharp Barber Shop Sign, Yuma, AZ, ca. 1990s.

©2003 John Margolies

©2003 John Margolies

John Margolies, a freelance photographer and writer, is photographing and researching America’s main streets and roadsides.