CAMBODIA–Phnom Penh–Micheline LaJoie, a forty-something, brassy blonde former real estate agent from Quebec, eased her hulking white Land Cruiser through curtains of bamboo into the Khmer Rouge village of Chrey Leung. Two weeks before, the Khmer Rouge had taken four United Nations peacekeepers and their Cambodian interpreter hostage here; they were cut loose the next day and warned to stay out of the village. But voter registration had just ended for Cambodia’s first “democratic” elections and this was one of the few Khmer Rouge villages where peasants had signed up. LaJoie, the top UN electoral official in this remote district near the Vietnamese border, wanted to fly the UN flag and keep her lines open to the Khmer Rouge.

Photo by Peter Charlesworth, JB Pictures

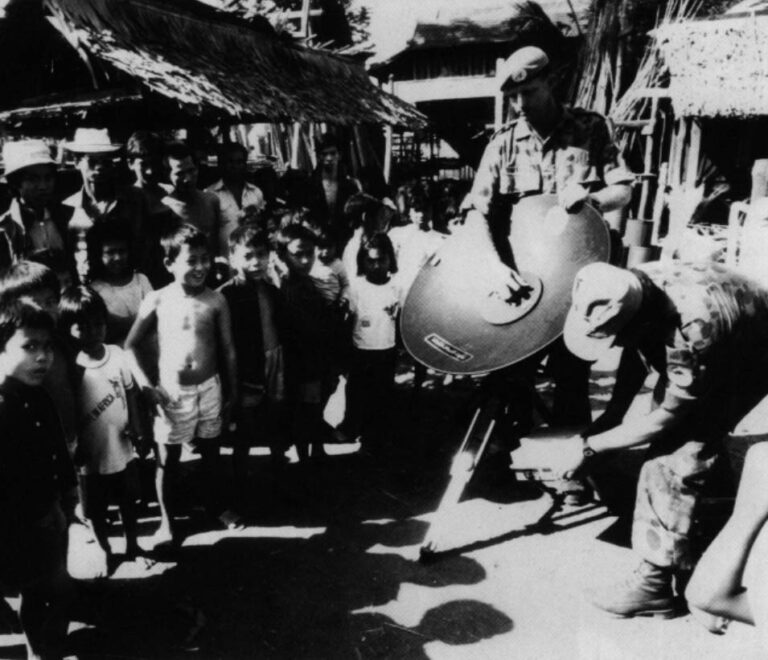

Our trek turned out to be the the kind of fuzzy search and witness operation that was the best the UN could mount against the rabid bloodlust of Cambodian politics. The usual crowd gathered as soon as our elephantine cruiser, straddling ox cart tracks, lumbered into the village. This was no bucolic Potemkin version of a Khmer Rouge village foreigners could tour until the cadres cut off all contact a month before the May elections. The huts were a shambles, and the villagers were in rags, too dazed by filth and hunger to gather themselves into much of a life. There were no men, except three bare-chested, posturing drunks and one severe young man, neatly dressed in a black shirt, khaki pants and rubber flip-flops. While he drew our interpreter back out of sight, a crowd of women, most of them topless and necklaced with still nursing toddlers, watched, mute.

Fearless from booze, the drunks reported they had registered to vote, but that the Khmer Rouge had confiscated the cards. As we tried to draw people into a conversation about voting and democracy, the talk ground to a halt. A visiting Bhuddist monk broke the silence: “If people want to vote and the Khmer Rouge say `no,’ they will come with guns. What can the UN do about that?”

“What indeed?” whispered LaJoie, as we watched the severe young man and two comrades walk toward us, now armed with AK-47s. We backed slowly out of Chrey Leung to the main road and streaked like bandits back to the district capitol.

Over a breakfast of noodle soup and coffee in the market the next morning, Lajoie swatted away intimations of heroism with the flies and admitted she wasn’t altogether sure what her dangerous, 14-hour, seven-days-a-week work would come to. “Maybe we support the courageous, maybe a few Cambodians will catch the democracy bug, maybe the children,”she ran down, concluding with a Gallic shrug.

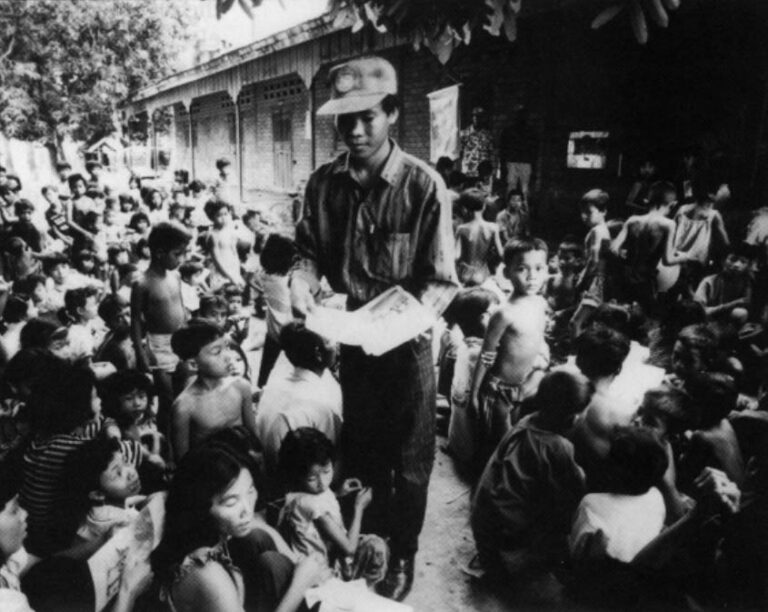

In March, 1992, the United Nations mounted its second biggest peacekeeping operation in its history–only Somalia is larger– dispatching nearly 17,000 troops and over 5,000 civilians at a cost of over $3 billion. The Cambodian peace agreement, signed in October, 1991, gave the United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC) the power not only to police a ceasefire, repatriate refugees and organize elections, but also to oversee an interim coalition government, oversee key government ministries, remove Cambodian officials from office, supervise the economy and install its own media. Or in New World Order lingo, not just peacekeeping, but nation building.

Photo by Peter Charlesworth, JB Pictures

At first, war-weary Cambodians welcomed the UN as a savior, the peacekeepers’ bloated white Toyota cruisers and baby-blue berets evoking the Cambodian mythological messiah, the white elephant with blue tusks.

But nearly two years later–although the recent elections were trumpeted abroad as a resounding UN victory–UNTAC’s actual accomplishments seem lackluster and pricey. (UNTAC’s official mission ended November 15, with only a few hundred peacekeepers left in Cambodia as observers). Three hundred and sixty thousand refugees were repatriated from Thailand, in the kind of logistical triumph that is the UN at its best. But UNTAC promises of land and a new life shriveled to $50 per refugee in cash or building supplies. And most refugees lost those alms to bandits before they got home.

The ceasefire never happened. The Khmer Rouge refused to disarm, the government responded in kind and fighting has resumed at pre-peace-accord levels. Peacekeepers in Cambodia came up against the brutal but simple truth–as they have in Bosnia and Somalia–that the UN can’t make peace if the local warlords won’t.

Rebuilding the war-torn, mismanaged and corrupt Cambodian economy remains a distant dream. The influx of 22,000 peacekeepers and billions of UN dollars bloated the economy to unnatural levels and political in-fighting between Cambodian factions blocked development aid until after the elections. Agriculture is still held hostage by the millions of mines lacing the countryside. UNTAC’s de-mining program is an utter flop: More than $9 million has been spent to remove only about 8000 mines, fewer than are now being laid by the still warring Khmer Rouge and government troops.

The Khmer Rouge remain unbowed. They are shut out of official power in the new government by their boycott of the elections. But they continue to battle in the countryside, murder Vietnamese settlers and menace Cambodian political life by their demands for power.

As for nation building, UNTAC’s ventures are reminiscent of the colonial misadventures George Orwell immortalized in his memoir “Shooting an Elephant.” Like Orwell’s Burmese subjects, the Cambodians often find it easier (and more amusing) to stand by and watch UNTAC try to save Cambodia than to try to do it themselves.

That the UN’s Cambodia kharma might turn out to be colonial was most clear in the wake of last May’s elections, which were heralded as the capstone of UNTAC’s crusade to convert Cambodia to democracy. To the amazement of UNTAC, diplomats, and journalists, the Khmer Rouge made only desultory attacks on a few polling places and even trucked in villagers to vote in some places. When asked what he made of the Khmer Rouge’s dramatic U-turn in tactics, Yasushi Akashi, the top UN official in Cambodia, threw up his hands in best colonial fashion and called the natives–the Khmer Rouge–“unfathomable.”

Photo by Peter Charlesworth, JB Pictures

Just as unreadable were the actual results of the greatly trumpeted elections. Three hundred polling places in or near Khmer Rouge zones were axed from the original plan; the remaining 1500 were in government-controlled areas. And privately, some UN officials admit that as many Cambodians may have voted out of a fear of the government as a love of democracy. What would the outcome have been without the five months of murder, violence, threats and bribery that preceded the vote?

No sooner had UNTAC gotten its magical turnout than Cambodian political leaders were showing that UNTAC had not much more power in the country than a fly on an elephant’s hide. Even before the vote was counted, Prince Norodom Sihanouk, Cambodia’s traditional leader before he was overthrown in a military coup in 1970, was meeting with the warring factions to form a coalition government outside the structures set up by the peace accord. The wily prince didn’t even invite anyone from UNTAC to these palace confabs. Outside the palace, crowds of Cambodian citizens the prince still calls “my children” waited for the man they still called “King.”

Special Representative Akashi was reduced on occasion to mediating between Sihanouk’s feuding sons in a kind of Cambodian version of Lear. One son, a government pooh-bah, used his power to block his half-brother, leader of the party that won the election by a hair, from landing at Phnom Penh airport at a critical moment in the machinations to form a new government.

Photo by Peter Charlesworth, JB Pictures

In the wake of the elections, Akashi had reverted to his most familiar bureaucratic tactic–naming even the deepest quagmire uncrossable. After months of threats by UN officials that the elections would be called off because of the violence–bluffs no Cambodian took the slightest bit seriously–Akashi certified the election “free and fair,” even before the votes were tallied. Then, after a week of handwringing over Sihanouk’s short-circuiting of the democratic process, UNTAC proclaimed the chameleon prince Cambodia’s only hope.

On September 24, Prince Sihanouk, proclaiming himself King, ushered in the new government he had arranged himself in feudal, Cambodian tradition. The new constitution, overwhelmingly approved in a secret ballot, gives the King the power to dissolve the National Assembly and appoint two prime ministers, one from each of the parties in the coalition government. An UNTAC spokesman quickly awarded the arrangement the UN imprimatur: “In general terms we’re satisfied it corresponds to the principles of the Paris agreement.” But many other observers privately believed the new government was nothing more than a creation of current Cambodian power politics and not a long term, legitimate or stable government structure. And it certainly wasn’t democratic, at least in Western, UN terms.

In the 1980’s, the Cambodians themselves had almost created a coalition government until the US and its allies, in a frenzy of anti-Vietnamese manipulation, blocked the effort. Had hundreds of lives been lost and billions spent to achieve something Cambodians could have achieved themselves–if they’d been left alone? Had UNTAC itself been “UNTACed,” a process wags in Phnom Penh define as “a method of extreme folly in which the result is the opposite of what was originally intended?”

What the UN and First Worlders find hard to accept is that force-feeding democracy creates a paradox: can democracy be produced through undemocratic methods? When UNTAC first arrived, officials explained to Cambodian politicians that democracy meant the Cambodians should determine their own political lives. But when UNTAC asked what suggestions they had for the voting, the Cambodians said that above all, they wanted to exclude any Vietnamese who lived in the country from voting. That would be undemocratic, UNTAC replied. But, said the Cambodians, we thought democracy meant the Cambodians were supposed to…and so on.

To get Cambodian politicians to listen, Akashi tried blackmail, using the carrot of future international aid, but it didn’t always work, especially in stopping political violence. That’s because Akashi was demanding that the same high-level government officials who ordered the repression arrest the perpetrators. Akashi finally decided the only way was for UNTAC police to investigate and arrest suspects themselves. Two suspects were duly produced–balanced politically correctly with one government and one Khmer Rouge murderer–and arrested. But the government refused to try them. Later, two more suspects were detained bu UNTAC. So the same UNTAC officials who were appalled by Cambodia’s “barbaric” criminal justice system ended up holding suspects for eight months without charges. (The Khmer Rouge prisoner died in UNTAC custody; two of the remaining suspects were turned over to the new government in late September).

“Democracy is a Western idea,” snaps a Chinese UN military observer, who nevertheless sports a T-shirt emblazoned with the motto of New Hampshire: “Live Free or Die” He added, “The UN is a Western institution. Asians think differently.”

To Cambodians, “democracy” and UNTAC do seem foreign. They are amazed by the outrage of First World idealists over the routine brutalities of their lives, like corrupt police, hospitals without medicine, schools without books, and the brutal feudalism of their rulers.

When they have any business with UNTAC, Cambodians often say they’re going to UNTAC country. UNTAC country is First World, full of air conditioners, phones that work, faxes, computers, oceans of paperwork, human rights, hamburgers, ice cream, lobster, MTV, females in shorts, appointment books, painkillers and oxygen tents, helicopters and huge white cars that mow people down. It’s a wild, multicultural bouillabaisse of Bulgarian, Uruguayan, Malaysian, Russian, Chinese, French, and other idealists, heroes, cowards, fools, diplomats, bureaucrats, soldiers, rapists, powermongers, money-grubbers, and rip-off artists.

Photo by Peter Charlesworth, JB Pictures

The possibilities of cross-cultural cognitive dissonance are boundless. Cambodian toddlers in the remote province where the Uruguayans were stationed hail strangers with a hearty “HOLA!” New Zealanders–“kiwis” to one and all–throw food orgies called “kai hangis,” said to be an aboriginal custom, in which slabs of meat and vegetables are buried in a huge pit to smoke. Three Cambodian interpreters invited to a recent “hangi,” during which shirtless revelers dug up the meal to a tape of a grunting, racist parody of Zulu military campaigns, were flabbergasted by the barbarity of the scene. Inside the compound, a Cambodian enforcer hired for the occasion delivered brutal whacks to an eight-foot-high chain-link fence to keep curious Cambodians at bay.

The sad reality of any UN operation is that for every idealist like Micheline LaJoie, who lived with a Cambodian family, struggled with the language, and enjoyed her Cambodian friends there are scores of lazy, greedy, ignorant, even bigoted peacekeepers. One African asked an Italian journalist, “Who is this Red Khmer I keep hearing about? Does she really have red hair? Is she really beautiful?” Some peacekeepers, especially those from Australia and New Zealand, referred to Cambodians and UNTACers from developing countries as “Third World doggies.” One UNTAC supervisor in Phnom Penh told her Cambodian staff they weren’t allowed to “sampeah” (bow) in respect to someone older or more powerful because it wasn’t “democratic.” One Chinese military observer trotted out that old racist canard from Vietnam that “the Cambodians don’t respect life like we do.”

Some peacekeepers, especially the Ghanaians, bought Cambodian “wives” to serve them sexually for their tours. (One Ghanaian got shot by enraged Cambodians). When First World UNTACers, aid workers and journalists held a press conference to decry sexual harassment and the rape of several Cambodian women by peacekeepers, Akashi dismissed the charges by saying that such high spirits should be expected from a large group of young men far from home.

The corrupting effect of 22,000 peacekeepers wielding $3 billion “UNTACed” any UN effort to reform the economy. Many UNTACers raked in $130-145 a day per diem on top of fat UN salaries in a country where the average yearly income is $140; many Third World peacekeepers joined UNTAC not out of commitment to the UN mission, but for the money. “UN employees are obviously better off than Cambodians. And it’s part of our mission to be visible. That just comes with the territory,” snaps one high level UN official in New York dismissively. “I could have accomplished everything we did in Cambodia with 3000 peacekeepers, “says one top UNTAC official.”if I could pick the 3000. But in the UN, political considerations not competence, rule.” Action can be taken to lessen the social cost of a UN occupation: the Dutch confined their troops to base at 6 p.m. and banned alcohol).

Of course it isn’t just the peacekeepers who are corrupted by their colonial lifestyle. “Cambodians have caught the Bangkok disease,” says one dismayed Australian. “Everything is for sale and will collapse when UNTAC leaves.” Top government officials sell the land underneath their ministries while underlings hawk their office furniture. Blood and medicine donated by international aid groups are sold to patients. UNTAC AIDS education only persuaded soldiers and businessmen to buy virgins, the younger the better; their strapped parents were only too willing to comply. Restauranteurs set up in Phnom Penh, made their investment back in a month selling pizza to peacekeepers and refused to pay their Cambodian employees.

Photo by Peter Charlesworth, JB Pictures

Many Cambodians fear the UNTAC-fueled money frenzy plays into the hands of the Khmer Rouge, who rode to power on rural rage against the dissipations of Phnom Penh. “Cambodia has become like a hungry little boy who eats too fast and too much,” says one Phnom Penh university student.

And as for the UN, it exits Cambodia less like the messianic white elephant with blue tusks than another Cambodian elephant of yore: the woebegone royal pachyderm said to have gone mad after Prince Sihanouk’s overthrow in 1970. Raging in his filthy palace pen with the ignominious title on his stall “mechant (mad) elephant,” he disappeared during the Khmer Rouge takeover and was reportedly eaten.

@1994 Judith Coburn

Judith Coburn, a freelance writer in Berkeley, California, has been reporting from Cambodia for two decades.