CAMBODIA–Thmar Pouk–The Khmer Rouge was a no-show. They were supposed to be there for the weekly meeting of the local “Mixed Military Working Group,” a United Nations-run network to police the Cambodian peace accord. Officers from the three other once warring Cambodian factions were there, but no one knew where the Khmer Rouge representative was.

Takeo, Cambodia-

Cambodia’s U.N. Military Chief Lt. Gen. John Sanderson, left, and Director general of the Japanese Defense Agency Sohei Miyashita, shovel sand on national route 3 during a ceremony marking the beginning of the Japanese U.N. engineering battalion’s repair of the road last fall.

AP/Wide World Photos.

Nor was there any immediate way of finding out. U.N. peacekeepers can’t just phone up the xenophobic Khmer Rouge or drop by local general Prum Sou’s villa. U.N. peacekeepers would have to go through the usual layers of go-betweens and days of missed connections.

AP/Wide World Photos.

In March, 1992, the United Nations mounted one of the biggest peacekeeping operation in its history, dispatching nearly 17,000 troops and more than 5,000 civilians to Cambodia at a cost of more than $3 billion. The United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC) aimed at nothing short of rescuing–two decades too late–the country the world turned away from while the Khmer Rouge-and American bombers exterminated one sixth of the Cambodian people.

In not only its size and cost, but its ambition, UNTAC’s mission was gargantuan. It was not just a peacekeeping operation in the traditional military sense. Aiming not only to police a ceasefire, repatriate refugees and organize elections–logistical operations the U.N. has experience with–the Cambodian peace agreement gave UNTAC the power to create an interim coalition government, oversee key government ministries, remove Cambodian officials from office, manage the economy and install its own media. Or in U.N. lingo: not just “peacekeeping” but “nation building.”

“Peacekeeping missions in the past just monitored ceasefires,” says UNTAC commander Gen. John Sanderson. “In Cambodia we have a political objective–to create a democratic government through free and fair elections.”

Phnom Penh, Cambodia –

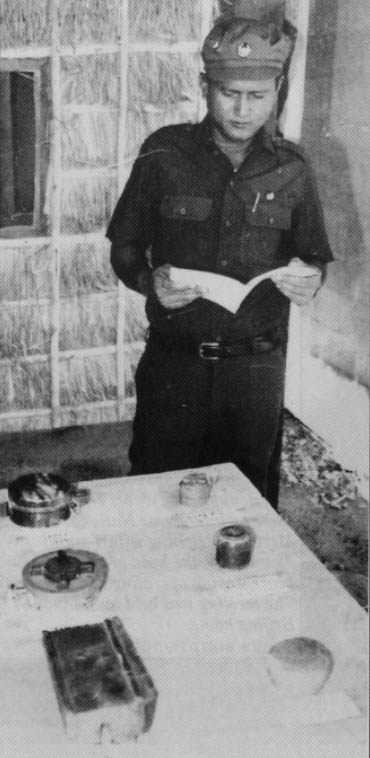

A khmer Rouge military official reads a Cambodian translation of the Paris Peace record behind a display of captured land mines at a guerrilla camp in northwestern Cambodia last May. The Khmer Rouge’s refusal to comply with the accord has threatened the U.N. sponsored peace plan.

AP/Wide World Photos.

Easier said than done. Down on the ground in Thmar Pouk, this particular morning, the Khmer Rouge defection put a distinct crimp in acting commander of the Dutch Marines Peter Buitenhuis’s agenda for the meeting. He’d hoped to lay out a plan for joint patrols with soldiers from all four factions plus the Dutch Marines to prepare for protecting polling places in the upcoming elections.

The captain, a smallish, compact and affable man who exudes an air suggesting it would be unwise to mess with him, shrugged off his baby blue helmet and flak jacket in the 110 degree heat. The Dutch Marines, many of them veterans of U.N. duty in Kurdistan, treat Cambodia like a combat zone, dictating full combat gear, bunkers and heavy armament.

The sight of bristling Dutch patrols swerving around civilians in shorts and flip flops on bikes fits Cambodia’s surreal now-you-see it-now-you don’t war. Out on what pass for battlefields, Khmer Rouge and government soldiers jockey for turf. One side shells before advancing, giving its opponent plenty of warning to leave before new territory is taken. Then the “victor” withdraws, is shelled in turn and the cycle reverses itself. There are few casualties.

The whole operation was a far cry from what the Dutch Marines expected. With the Australians, the French and American military observers, they are the hard chargers of the UNTAC mission. Their original assignment was Pailin, deep in Khmer Rouge territory near the Thai border. But when their first convoy tried to cross into Cambodia, in May 1992, it was blocked by Khmer Rouge troops. In an even more blatant slap at the U.N., the Khmer Rouge refused to let UNTAC head Yasushi Akashi and Gen. Sanderson into Pailin to mediate. The U.N. never got entry to the area.

In short order, the Khmer Rouge also refused to disarm and to send its soldiers into the demobilization sites called for in the peace agreement. In response, the Cambodian government, after demobilizing some 30,000 of its troops and surrendering the most decrepit of their weapons, stopped disarming.

The immediate collapse of its peacekeeping mission set off recriminations in the UNTAC military command. French General Michel Loridon, Sanderson’s deputy, was eased out because he disagreed with Akashi’s and Sanderson’s diplomatic approach to Khmer Rouge intransigence. Many soldiers, especially the Dutch, the French and the Americans thought Sanderson should have gone on the offensive and pushed into Khmer Rouge territory at the onset, even if it meant casualties.

“Akashi and Sanderson are too determined to keep everyone inside the accord. But it’s an empty shell. The U.N. is panicked by failure because of Bosnia and Somalia,” says one top UNTAC official.

Sanderson was so wary about offending the Khmer Rouge that U.N. military observers under Khmer Rouge house arrest in Pailin were left there for months.

“Because we don’t shoot Cambodians, some people think UNTAC is weak,” said Sanderson in a recent interview. “Every peace force is seen that way. We seek compliance by political means.”

Conflict in the Phnom Penh command only exacerbated the usual divisions in the field in multi-cultural operations. While the Dutch and the French aggressively patrolled their territory, Bangladeshi troops hid under their bunks during one attack on Siem Reap. A first contingent of Bulgarians had to be sent home after they got into a fire fight with government troops over who controlled the whorehouses in their zone. No country contributing troops–except the French–allowed their soldiers to risk de-mining except as supervisors, leaving a few hundred hastily trained Cambodian de-miners to deal with the millions of mines in the country.

Many troops considered themselves under the command of their own leaders back home rather than Sanderson. Electoral officials in Kompong Thom often heard Indonesian officers there calling Djakarta for orders. The Indonesian strategy–and they were not alone–was to avoid conflict, not police the accord. Troops refused to fly in electoral teams to register soldiers in one site because they feared the Khmer Rouge would be angry. “In government controlled areas they went along with what those guys said,” reports one disgusted UNTAC official in Kompong Thom.

Lack of a common language among troops caused chaos, especially in radio communications. Electoral officials in Kompong Thom often couldn’t call for help on the radio because so few Indonesians spoke English or French. The Indonesians didn’t seem to feel rescuing fellow UNTACers was part of their job. One American U.N. military observer being held by Khmer Rouge with a gun to his head watched an Indonesian patrol speed right by without ever slowing down. A Japanese electoral official and his Cambodian interpreter lay bleeding for an hour on a Kompong Thom road after being ambushed because they couldn’t raise the Indonesians on the radio Both died.

AP/Wide World Photos.

Stymied by the Khmer Rouge, Dutch marines were garrisoned instead at Thmar Pouk, deep “in the zone”, the so-called “liberated” area of northwestern Cambodia, where American, Chinese and Thai aid has kept Khmer Rouge, anti-communist and Sihanoukist warlords contented for more than a decade. Their enemy, the Phnom Penh government, which was installed by the Vietnamese in 1979, has no presence in “the zone.” There, the Thai money is king and making money the only real cause. Multi-storied stucco villas ringed with moats or barbed wire dot the blasted countryside, once a free fire zone for Vietnamese-Khmer Rouge battles. Because the government stays out of the zone, there are few cease fire violations. But the gung-ho Dutch marines, American military observers and Australian police watch disgruntled as gem and timber smugglers zip up and down the smooth American-built roads.

Heavily armed bandits, whose warlord patrons have parceled out each road to a different brigade, rip off Cambodian travelers every few miles.

It isn’t really very clear to the peacekeepers in the zone just what they’re doing, given that their major job, policing the ceasefire and disarming troops hasn’t happened. The bandits tend to lie low when the Dutch Marines are around, so they busily ply the roads and Cambodian civilians form convoys behind them for protection. The naive myth has grown up among UNTAC that the zone is some kind of peacekeeping model for the rest of Cambodia. A single checkpoint near Thmar Pouk at Svey Chek manned by all four factions, a police training program for all factions run by the Australian police and the mixed military working groups, are supposed to show the Cambodians can work together. But as the U.N. has found in Somalia and Bosnia, it can’t make peace when battling warlords don’t make peace themselves.

The Khmer Rouge is like Cambodia’s errant uncle, just paroled for murder, who shows up uninvited for the family’s New Year’s feast. No one is sure whether it’s more dangerous to invite him in or to shut him out. UNTAC, and especially denizens of the zone believe in civilizing the Khmer Rouge. Instead of trying the Khmer Rouge for genocide, the argument goes, you welcome them into the peace process and they’ll change their murderous ways. A kind of creepy “Khmer Rouge chic” has grown up among many peacekeepers. Some younger UNTACers, eager to create their own reality, believe there’s a new generation of Khmer Rouge that is different and enjoy shocking their elders by saying so. “I got no problem with the Khmer Rouge,” said Capt. Jeffrey Jaso, an American U.N. military observer in Thmar Pouk in March. “They’re nice guys.”

Many electoral officials, faced with personal threats or witness to political violence by government soldiers, felt more menaced by Phnom Penh than the Khmer Rouge, with whom they had little contact.

“It’s human nature, people have a harder time killing people they know, that’s why we try to befriend the Khmer Rouge,” said one Australian policeman as we set off for the wedding of a Khmer Rouge commander’s son.

Yasushi Akashi, head of the U.N. Transitional Authority in Cambodia listens as Prince Norodom Sihanouk speaks at an emergency meeting in Beijing this May. The subject was the deterioration of the Cambodian peace process, but the Khmer Rouge did not attend.

AP/Wide World Photos.

It doesn’t occur to many peacekeepers–most of whom had zero experience in Cambodia–that Khmer Rouge “nice-guyness” might be a united front tactic. Or that keeping UNTAC out of their zones might allow the Khmer Rouge to veil their brutality.

But in visits to several Khmer Rouge villages, including one in eastern Cambodia where peacekeepers had been taken hostage two weeks before, it was clear the Khmer Rouge still rules by fear. “You talk about democracy,” said a monk in Chrey Leung village near the Vietnamese border. “But the Khmer Rouge has guns.” While he whispered, armed Khmer Rouge soldiers evesdropped and then ordered reporters out of the village.

Once the Khmer Rouge began taking peacekeepers hostage and, in April, abusing and killing them, UNTAC’s strategy of civilizing the Khmer Rouge seemed bankrupt. Capt. Jaso got angry and confronted a local Khmer Rouge general about how the Khmer Rouge could keep asking for UNTAC rice and medicine and turn around and attack peacekeepers. “Because UNTAC isn’t very smart,” the general replied.

The Bulgarians in Kompong Speu, south of Phnom Penh, found out just how duplicitous the Khmer Rouge can be. Over the months they’d struck up a friendship with a Major Don, the local Khmer Rouge commander. They’d shared rice together and Bulgarian military doctors had treated his pregnant wife. So on the evening of April 12, when Major Don showed up with two of his armed bodyguards, they were invited to take showers and share a meal. Within minutes, six of the Bulgarians were shot execution style, leaving three dead and three critically wounded.

But like militarymen everywhere, UNTAC peacekeepers carry on. In Thmar Pouk, in early March, Capt. Buitenhuis forged ahead at the mixed military working group without the Khmer Rouge. The Captain asked the representatives of the three factions present why the Khmer Rouge were permitting them to move back and forth across the Thai border and U.N. peacekeepers were not. (Unspoken was the reason for his frustration: that the U.N. had been unable to put a dent in gem and timber smuggling across the border even though all four factions had dutifully endorsed a U.N. ban in Phnom Penh). There was a long silence. It was interrupted by the only business the Cambodians all agree is the reason for these meetings: to cut deals for UNTAC goodies. How could this general get another generator from UNTAC? How could that general get UNTAC to move their chopper pad so he could build a market there? When could this or that village get more radios?

AP/Wide World Photos.

The military observers groaned. The frigging radios. Five hundred thousand of the bloody things had been donated by the Japanese, many of them broken, none with batteries, and they’d created the biggest violence problem the peacekeepers in Thmar Pouk had to grapple with. Many had been liberated from UNTAC storage before they were even distributed. Those that were, were ripped off from the Cambodians lucky enough to get them. Five Cambodians in the zone had died over radios. Villagers who got radios kept showing up complaining about no batteries, so UNTAC had to buy and distribute them.

“Am I a soldier or a damn K-Mart clerk?,” grumbled Capt. Jaso, who was spending evenings ripping power cords off radios and inserting batteries.

“At least we’re trying,” said Capt. Buitenhuis as the meeting broke up and he prepared to hit the 110 degree heat. “We’re giving the Cambodians some breathing room. Banditry is down, people are building houses, a kind of life has sprung up.”

“But I also remember what happened when we spent three months in northern Iraq after the Gulf War so the Kurds could move back to their villages,” he continued. “A week after we left, the Iraqis moved back in and the Kurds had to flee.”

@1993 Judith Coburn

Judith Coburn, a freelance writer in Berkeley, CA., has written about Cambodia for more than two decades.