In the mythology of the Underground Railroad, the Ohio River has a sacramental status. Crossing it transformed slaves into free men and women. The alchemy was imperfect, to be sure: Under federal law, slaves in the North remained property and could be recaptured. Still, reaching the free state of Ohio from Kentucky was a critical step in a pilgrimage that led to Canada and safety. Now, this voyage, undertaken by thousands of slaves before the Civil War, is being commemorated in a landmark museum on the Cincinnati waterfront.

Slated to open in 2004, the $110 million National Underground Railroad Freedom Center is a grand undertaking that grew out of a modest notion. The local chapter of the National Conference for Community and Justice (formerly the National Conference of Christians and Jews) proposed the center in 1994 as a way of marking its 50th anniversary and its mission of fostering cooperation across racial, religious and ethnic lines. The center’s dual identity is embodied in its name. The Underground Railroad story, already told at various sites around the region, has been enlisted here to stand for the broader idea of freedom. “Initially, I thought it was a really big leap,” says Rita Organ, the Freedom Center’s director of exhibits and collections. “Now, I’ve bought into it.”

Will the rest of the country? The answer depends on how artfully the Freedom Center can sell its message of interracial cooperation and reconciliation — and how ready its audience is to hear it.

The Freedom Center is reflective of a new convergence between African American and American history. It’s a trend evident in the increased attention to slave history at iconic places such as Mount Vernon and Monticello, in the painstaking restoration of slave cabins at plantations such as Boone Hall near Charleston, S.C., and in the latest reenactments of 18th-century life at Colonial Williamsburg. Edward Ball’s prizewinning 1998 study, Slaves in the Family, is a product of this convergence, and DNA evidence attesting to the Sally Hemings-Thomas Jefferson liaison is its great symbol. “We’re not an African American museum,” Organ says of the Freedom Center. “We’re an American museum, trying to tell American stories.”

The Freedom Center also is indebted to another trend, the proliferation of so-called museums of conscience. The U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, the Museum of Tolerance in Los Angeles and the Lower East Side Tenement Museum in New York are all important models. The Freedom Center has defined itself as a site of moral transformation, where visitors may be inspired to follow in the footsteps of such heroic figures as Harriet Tubman, Quaker abolitionist Levi Coffin and others who risked their lives to lead slaves to freedom.

“We’re a safe house for preparing modern-day freedom conductors,” is how Edwin J. Rigaud, founding president of the Freedom Center, expresses this notion. “That’s learning about the history, that’s learning about the contemporary implications of the history, and that’s being inspired to action — it’s all those things.”

At the same time, the Freedom Center exemplifies the idea of museums as economic anchors, and of history as entertainment. Backed by hefty corporate and government funding, it is, very pointedly, a “center” rather than a museum — a word meant to convey a dynamism missing from stodgy old history museums. Cincinnati has donated land along its waterfront to the project, which is sited between new football and baseball stadiums in an area modishly re-christened The Banks. Procter & Gamble, one of Cincinnati’s leading corporations, has donated $6 million, as well as the services of Rigaud, a P&G executive with no professional museum experience. The Freedom Center picked Jack Rouse Associates, best known for its work on theme parks and corporate museums, as production manager and executive producer of its exhibitions.

In September of last year, the center bolstered its academic credibility by nabbing Spencer Crew, the well-regarded director of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History and a scholar of African American history, to serve as its new executive director and chief executive officer. (A previous director, John Fleming, had stepped down, saying his power-sharing arrangement with Rigaud was unworkable.) Under Crew’s leadership, the museum is aiming to attract 450,000 visitors a year — and gin up tourism dollars for Cincinnati.

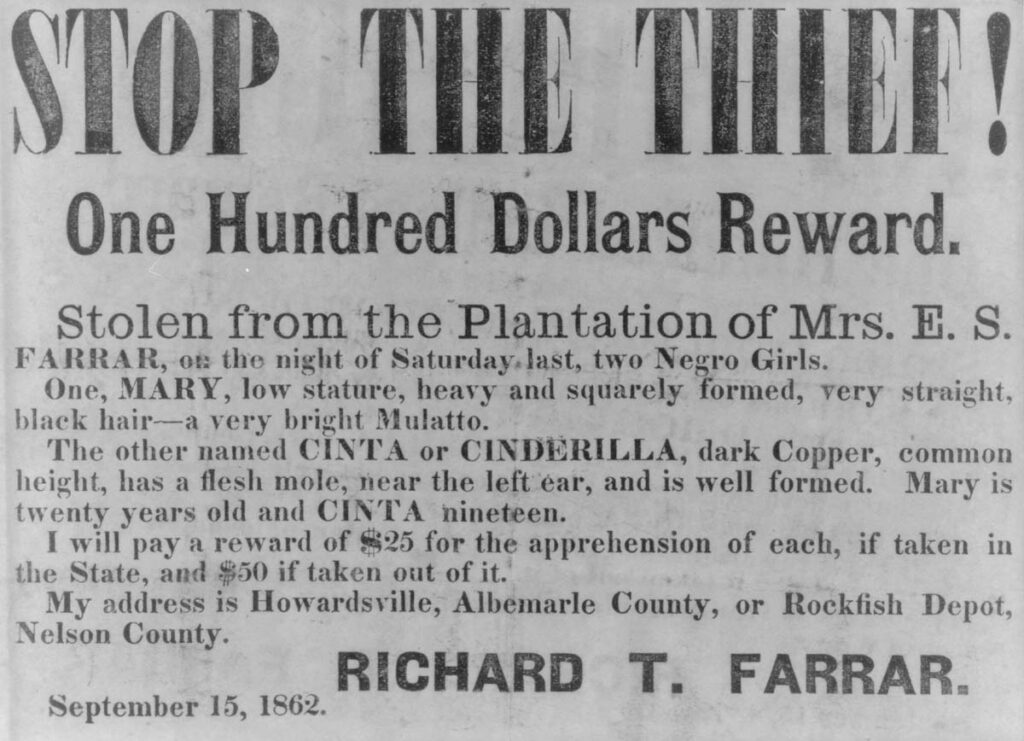

It’s an ambitious agenda, to say the least. The center will be the first truly national museum to attempt to interpret the history of American slavery to a racially diverse audience. Its planners promise an “unflinching” view of the story. But there’s a danger that a focus on the Underground Railroad, a determinedly upbeat message, and the need to attract big crowds will soften or distort its presentation.

Linking the history of slavery with the concept of freedom is a daring move. Freedom can be relative, and it’s unclear how the museum will define it. “Freedom means different things to different people,” Organ says. The Freedom Center’s goal of inspiring social action is still a cutting-edge concept for museums, and some of its proposals — including small-group dialogue led by trained facilitators — are virtually untested in museum settings.

“It’s a risky venture, in an area not known for risk-taking,” says Deborah L. Mack, who left her post as director of public programs in October 2000. “There were so many expectations being loaded onto it [the museum] that I think it began to suffer from it. There are not any clear preexisting models for what the Freedom Center is trying to do.”

By identifying as an American, rather than African American, museum, the Freedom Center has embraced the tricky project of communicating about race to racially diverse audiences. Finding the right voice, or voices, for its narrative will be tough. Race, after all, still affects how most of us interpret the world. Mack points out that most African Americans believed the story of Sally Hemings’ liaison with Thomas Jefferson all along. It was whites who needed to see the DNA evidence.

“It’s always been assumed that this [the Freedom Center] would appeal to African Americans,” says Paul A. Bernish, a board member who did public-relations consulting for the center. “The question is whether it will appeal to white suburbanites.”

Rigaud emphasizes the symbolic significance of his own multiracial, multiethnic background, with ancestors that include African Americans, Native Americans, Asians and European Americans of Irish, Spanish and French extraction. “People say, ‘How can the descendants of slaves and slaveholders get together? I don’t see how.’ Well, I’m the descendant of slaves and slaveholders — and if I can’t resolve it, I’m in trouble.”

He argues that the Freedom Center, based in a city that has recently seen its own share of racial upheavals, can be a key player in this country’s quest to overcome its heritage of oppression. “We have this dichotomy of freedom for all, but not for all, that we had to resolve — and this is the struggle to resolve that,” he says. His vision of outreach includes not just a Web site and a center for genealogical research, but a network of “freedom stations” around the country. The stations, which will be located in African American museums, colleges and other locations, will have digital access to the museum’s collections and exhibitions–and will expand the impact of its programs in ways that are still evolving.

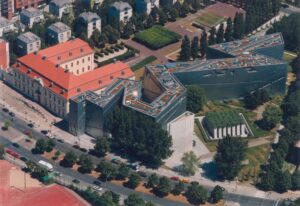

The Freedom Center’s architectural design, by Blackburn Architects of Indianapolis and BOORA Architects of Portland, Ore., pays tribute to the center’s utopian underpinnings and to the idea of architecture as a form of storytelling. The 158,000-square-foot facility, which faces the Ohio River, consists of three pavilions linked by bridges. Alpha Blackburn, president of Blackburn Architects, says the structure represents “an unusual alliance–a kind of cooperation among people that speaks of community as much as it speaks of the single person’s yearning for freedom.”

The ruggedness of its heavy stone walls is “a reference to stone as something permanent,” and to the flagstone walls of rural Kentucky. The gentle curves of the building refer, she says, “to the ebb and flow of the river itself,” as well as of life. The building’s use of glass will create “a certain transparency for people outside the building, for whom the subject matter might seem heavy or oppressive,” she says. In addition, symbolic paths to freedom that begin in the landscaped park outside will continue through the building and welcome visitors in.

Will the museum’s contents also be welcoming? Serious content itself is not necessarily a turn-off. Exhibit A is the phenomenally successful U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, to which Freedom Center planners refer frequently. Two million visitors a year flock to this museum near the National Mall to see grim images of starvation and slaughter. Resisters and rescuers are mentioned, but are overshadowed by the chronicle of devastation — precisely the opposite of the effect intended by the Freedom Center.

But there’s another salient difference as well. While the Holocaust Museum does use American democratic values to critique not just Nazi Germany but the inadequate U.S. response to the Holocaust, the story it tells is still mostly a European one. Slavery, by contrast, is our legacy–impossible to distance or deny, and difficult to forgive.

But forgiveness is precisely the point at the Freedom Center, although, says Blackburn, “healing can’t come without an open acknowledgment of the deep wound, and how it was inflicted.” How direct that acknowledgment will be is uncertain. Rita Organ says that visitors will begin with a multimedia “opening experience” that will express the core themes of “courage, cooperation, perseverance and the quest for freedom.” It also will set out the roles of “oppressor, victim, bystander, ally and freedom-seeker ” — categories reminiscent of Raul Hilberg’s typology for the Holocaust, which includes victims, perpetrators and bystanders.

The first of two core exhibitions, tentatively titled “Freedom, Slavery and Freedom,” will cover the period of 1776 to 1865, from the Declaration of Independence to the end of the Civil War — a choice that overlooks the 17th-century origins of slavery in North America. The second, “The Struggle Continues,” will cover 1865 to the present. It won’t limit itself to race relations in the United States — a large enough topic. Instead, says Organ, it will “get a little more global” and examine what she calls “national and international freedom movements.” She lists apartheid in South Africa, the American civil rights movement, the protests at China’s Tiananmen Square, the suffrage movement and the international women’s movement as likely topics.

As for the Underground Railroad itself, it’s not clear how much of the story of this informal secret network of safe houses, routes and conductors will be told in these two exhibitions. But the metaphorical railroad will take center stage in the Boeing Flight to Freedom Story Theatre. Organ calls this an “environmental theater” that will use both live actors and media to provide “an emotional escape experience, as opposed to a physical one.”

The most problematic part of the Freedom Center concept, as Organ is quick to concede, is how to move from history to action. She says that audience research and consultation with experts has revealed that “people don’t really mind talking, but don’t know how to listen.”

The center will offer a variety of ways for visitors to express themselves, including “feedback stations.”

Rigaud at one point said he wanted the center to host ongoing discussions, with provisions for an audience to listen in. Organ has since said that the idea of a gallery for listeners has been jettisoned, but not the discussions themselves. “We know we have to have trained facilitators,” she says. And still: “Some [of the discussion] is going to be angry, some’s going to be ignorant, some may not be very effective.”

The center will also refer visitors to community organizations such as the National Conference for Community and Justice, the NAACP and the Urban League. “We’re not positioning ourselves as an advocacy institution,” Rigaud said in the fall of 2000. “We’re not going to take a stance on issues like reparations — or at least not immediately, because I don’t think we have the credibility to do that…But we do want to provide a forum where I think people can learn about those things.” By last March, however, he was willing to go further, saying: “We are moving towards being an advocate for freedom issues regardless of how controversial they may be.”

Like many nascent museums, the Freedom Center has had its share of growing pains and turf battles. One outspoken critic has been Charles Blockson, a Philadelphia historian who has done seminal research on the Underground Railroad and was instrumental in bringing national attention to preserving its sites. “What upsets me…is that all the money is going to Cincinnati now,” says Blockson, referring to a recent $16 million federal appropriation. “My main emphasis is preservation. If we didn’t push, there wouldn’t be any museum.”

Rigaud admits that there has been friction with preservationists, who also have received federal dollars, and he says he’s worked to ease it. “I tried really early to make peace with some of the leaders and made some progress,” he says. One impediment, he says, may be the multicultural makeup of the board. “The impression of some people will be that it’s not black enough, and therefore it’s being compromised” — the same kind of infighting, he says, that kept an African American museum from being built on the National Mall. (The National Museum of the American Indian got the nod instead, but a National Museum of African-American History and Culture has recently gained congressional backing.)

There have been internal missteps as well. The first draft storyline prepared by Rouse Associates was mistakenly sent to the center’s national advisory panel of historians before being vetted by staff. “They hated the document. It didn’t reflect their thinking,” Rigaud says. “We trashed it.”

Mack resigned from the Freedom Center in a struggle over what she calls “control of the message.” (Organ, who took her place, says the restructuring was necessary to get planning up to speed.) Mack said the center was choosing a corporate rather than a professional museum model and de-emphasizing research and collections. Crew’s recent appointment, however, may signal a new earnestness. In any case, the Freedom Center’s internal debates reflect “a natural clash of points of view,” Bernish says. The historians want the place to be “historically accurate down to the last footnote,” he says, while exhibit developers insist “it’s also got to be entertaining enough so that people will want to come back.”

No one believes the process of reconciling these aims will be easy. “We can’t provide an unflinching portrayal without offending someone,” concedes Organ. “It is risky. But I think we will be touted for it.”

Susan Redman-Rengstorf, vice president for development and public affairs, adds a note of caution. “Our biggest challenge is not over-promising something that we can’t deliver,” she says. “If the race problem in our country was as easily solved as some of our mission statements made it sound, there would be no need for the Freedom Center.”

©2002 Julia M. Klein

Julia M. Klein is a cultural reporter and critic based in Philadelphia.