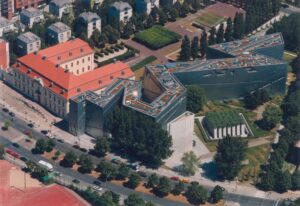

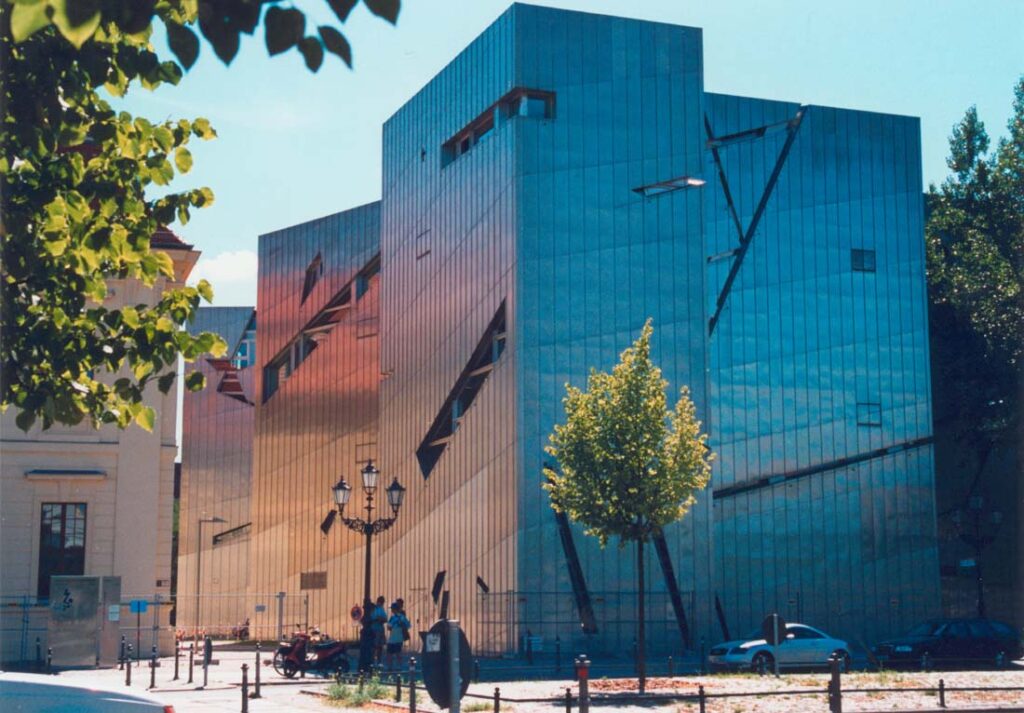

BERLIN – Like a streak of lightning or an unraveling Star of David, the Jewish Museum Berlin zigzags through this city’s Kreuzberg section, just steps away from graffiti-covered storefronts and boxy, high-rise public housing. Clad in zinc, its façade broken by irregular slashes of glass, it gleams like a spaceship in an alien landscape.

Thanks in part to its wondrous incongruity, Daniel Libeskind’s award-winning building has become one of the new German capital’s chief tourist magnets, attracting hundreds of thousands of visitors. One day, while a policeman watched for terrorists outside the empty museum, a few tourists wandered the grounds, snapping pictures. Others explored the few corridors still open while workmen completed upgrades to the building’s infrastructure.

Conceived in the 1970s and originally intended as a division within the Berlin City Museum, the $87 million Jewish Museum was set to open the week of September 9 with an exhibition tracing the history of Jews in Germany from Roman times through the present. That opening date – a response to political pressures, museum staffers say — has obliged them to compress what is normally five years work into some 18 months. “Some of us were really skeptical about whether we could manage that..,” said Thomas Friedrich, head of exhibition research.

But, given the museum’s difficult subject matter and its location, the time constraint was hardly its only challenge. One major hurdle was finding a way to address ideologically and experientially diverse audiences, from American and German Jews to non-Jewish Germans of different generations – as well as other tourists with more curiosity than knowledge. Can the sons and daughters of victims and the sons and daughters of Nazi perpetrators find common ground here?

The museum, which will be bilingual throughout, pledges both to use “good scholarship” and to entertain. But can it be both broadly appealing and intellectually serious? Like the best new museums, will it genuinely illuminate historical controversies, deconstruct the interpretative process, or try to move its visitors to action?

There’s also the question of what perspective its narrative will adopt on some key issues. Will it view the Holocaust as the logical culmination of German anti-Semitism, or as an avoidable catastrophe? How much complicity will it attribute to the “ordinary Germans,” about whom Americans Daniel Goldhagen and Christopher Browning have written dueling books? Will it discover some sign of redemption in contemporary Germany’s growing Jewish presence?

Most likely the museum, which promises to be a “welcoming and safe” place, will end its story on a modestly upbeat note. But other details remain under wraps. It is known that the permanent exhibition will take a largely chronological approach. Museum documents say it will “present German-Jewish history and culture through the narratives of achievement, persecution, presence and absence, survival and regeneration.” Personal stories, quotidian objects and traditional display techniques will be used, as well as dramatic lighting, architectural environments, computer interactives and eventually a theatrical presentation of some sort, according to project director Ken Gorbey.

Gorbey, a New Zealand archaeologist, is best known for his work in developing that country’s national museum, Te Papa, which bills itself on its Web site as “different from any other museum on the planet” and promises visitors “state-of-the-art time travel and virtual reality thrills.” Gorbey says Te Papa is a “celebration of New Zealand culture” – and that here in Berlin he knows he is dealing with “a history that cannot in reality be celebrated.”

At the same time, he and director W. Michael Blumenthal, a former U.S. Treasury Secretary and onetime German Jewish exile, stress that theirs is not a Holocaust museum. Even the section on the Holocaust will concentrate less on its horrors than on Jewish responses. “We don’t want to ignore the concept of perpetration, but to visit a guilt trip upon the German people is not the primary objective of this museum,” Gorbey says.

Still, the shadow of the Shoah hangs over the institution, Gorbey concedes, threatening both to simplify the complex weave of German-Jewish history and to complicate visitors’ reactions. Libeskind’s building, a symbolic narrative of the impact of the Holocaust on German Jewry, surely will function as a memorial to loss, even if the museum’s exhibitions choose other emphases. (Many critics have even suggested that it be left empty — a notion that Libeskind himself has rejected.) Gorbey maintains that the exhibition will complement the architecture. Libeskind’s architectural “voids,” for example, will be matched by a “gallery of the missing” that will commemorate the destruction of Jewish cultural property.

Berlin’s first Jewish museum had the bad timing to open in 1933 shortly before Hitler became Germany’s chancellor. It was shuttered by the Gestapo in 1938. Its successor, funded by the city and national governments and billed as Europe’s largest Jewish museum, is one of a troika of projects designed to fill out Berlin’s already crowded memorial landscape. The German Parliament has approved construction of a memorial to the murdered Jews of Europe — a vast field of slabs, along with an underground information center, designed by Peter Eisenman. The Topography of Terror, a museum about the Nazi perpetrators sited where the Gestapo and SS headquarters once stood, has been stalled by spiraling cost estimates.

All three projects are arguably a product of the Federal Republic of Germany’s ongoing efforts to express its contrition for the Nazi era and establish its bona fides as what the Germans like to call “a normal nation.” Blumenthal has said that the Jewish Museum Berlin will make vivid what the country lost in murdering or forcing into exile most of its 500,000 Jews. (Today, primarily because of an influx of Russian Jews, Germany’s official Jewish population is about 85,000.) The museum’s opening will be a victory for memory — but also a vindication for those Germans who celebrate “the new Berlin” and the new Germany, distant enough and detached enough from the past to confront it honestly.

With Germany’s self-image on the line, it is hardly surprising that the museum has been subject to intense critical scrutiny here. It also has weathered some internal shakeups. Consultant Shaike Weinberg, the indispensable man who helped create Tel Aviv’s Museum of the Diaspora and Washington’s U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, died in January 2000. The museum’s deputy director Tom L. Freudenheim left six months later, saying that his expertise hadn’t been appreciated. With both Weinberg and Freudenheim gone, Michael S. Cullen, whose contract as head of research was not renewed, said he feared that the museum was becoming a “Jewish Titanic.”

Blumenthal, author of a family memoir called The Invisible Wall: Germans and Jews, A Personal Exploration, took over as director in December 1997 and has continued to commute to Berlin a week or two each month from his Princeton, N.J., home. His signal accomplishment — as even his adversaries concede — was severing the museum’s relationship with the Berlin City Museum and convincing the federal government to run and fund it. He also expanded the museum’s focus, from just Berlin Jewry to all German Jews.

In April 2000 Blumenthal brought in Gorbey, who had been a consultant to the Jewish Museum, to supervise its completion. Gorbey, in turn, hired his Te Papa colleague, novelist Nigel Cox, as head of visitor experience. Wuerth and Winderoll, who had worked on Bonn’s innovative Haus der Geschichte, took on design responsibilities last summer.

When the museum’s proposals, including both an “academic concept” and a “visitor experience” plan, were presented to its academic board of advisers and its board of trustees, several ideas created dissent.

Coming under fire was the museum’s emphasis on “customer satisfaction” and multimedia technologies which evoked comparisons to Disneyland. The plan promised an 85 percent satisfaction rating. One proposal would have allowed visitors, using computer role play, to “have the chance to see if they can survive as a ‘U-boat,’ [a Jew] underground in Berlin during the war. ” Another involved a fictional café scene — reminiscent of the one at Los Angeles’ Museum of Tolerance — in which German-Jewish scientists Albert Einstein, Fritz Haber and others debated “the big issues of assimilation and threat.”

Der Spiegel, a leading newsmagazine, described the New Zealanders’ ideas as “interactive hocus-pocus,” and Thomas Lackmann, an editor at Der Tagesspiegel, published a derisive book called Jewrassic Park. Cullen says he still fears that the museum will become a “P.T. Barnum kind of place.”

Both the café and U-boat proposals have been scuttled. But Blumenthal has said that the museum is not being designed for “the intellectuals, the historians or journalistic snobs.” Cox, who says he acts as an “audience advocate,” says critics have been “over-reductive” in suggesting a museum’s only options are to be traditional or Disney-like.

Still, his most daunting opposition may be coming from within the museum. Friedrich says that the term “visitor experience” is foreign to Germans — and essentially untranslatable. He says he disliked both the “U-boat” interactive (“ridiculous and terrifying,” he calls it) and the café scene (“naïve”), and remains committed to “authenticity” in museum displays.

Inka Bertz, the museum’s head of research and collection, doesn’t see entertainment as a priority. “I think museums should…speak with authority,” she says. “I see a danger, if you’re being too much part of a culture industry and an entertainment industry, you just lose that authority.”

Cox admits that staff discussions can be “brutal.” Gorbey, who like Cox speaks no German and has no expertise in German-Jewish history, says his job is to find some reasonable mean. “You have a range of points of view. And they all…have to be listened to…from something that might sound incredibly traditional – ‘We will only put on display real objects’ – through to people who want to recreate in an absolute sense an environment and have an all-singing, all-dancing robotics display. Which we can’t afford,” he says. “But somewhere in the middle there is something that is appropriate to this particular story, and to this particular culture.”

There are other concerns as well, including a possible shortage of artifacts to display and how the museum will deal with historical controversy and complexity. Bertz says the museum’s own growing collections will be supplemented by loans. But Chana C. Schuetz, deputy director of Berlin’s Centrum Judaicum, maintains that, since Freudenheim’s departure, the Jewish Museum has had little contact with other institutions that collect Jewish objects.

What, Schuetz asks, will the Jewish Museum show? “A Torah curtain itself is not a very interesting object,” she says. “Can you give me one Jewish object that is not a Holocaust object that can be that impressive? They shouldn’t think to buy furniture of people who immigrated to the United States…makes a good object. It’s still old furniture.”

The furniture acquisition comes up a lot, and Friedrich defends it. The point, he says, is “to show people that these things exactly looked like everything else. They’re not Jewish.” He adds: “You know what kind of prejudices and cliches and stereotypes are there.”

With that point at least, Schuetz agrees. “You are dealing with people who have never seen in their lives a Jew, and they are full of prejudice,” she says. The museum, she says, won’t be able to take the risks her own Jewish-run center can, as in an exhibition that discussed Jewish wartime collaborators, “Jew-catchers,” in Berlin – and named names. “I promise you everything will be politically correct because they are very afraid of making any mistakes,” she says.

Gorbey says the museum’s approach will be based on market research. At Te Papa, which had an astonishing 4 million visitors in its first two years (New Zealand’s population totals 3.8 million), such research showed that “we always underestimate the intelligence of the visitor, but we always overestimate what they know.” Cox says most Germans already think they know quite enough about Jews — unsurprising considering how much attention Holocaust-related subjects receive in the German media. But, he adds, “A lot of people don’t know as much as they think they know.”

But how to pitch the lesson remains a matter of debate, says Cilly Kugelman, head of the museum’s education department and one of the few Jews on its staff. “The biggest discussion is how to do it in a way that people without big knowledge would understand it, and how to make it easy to grasp without giving up on the complexity of history…,” she says. “These are contradictions that have to be put together…I don’t know whether we’ll solve it. But we’ll try.”

Kugelman rejects the notion that to be entertaining is to be simple-minded: “Entertainment is also to raise curiosity, to present puzzles, to introduce people to paradoxes, to give them something to think about – to make people leave the place with questions rather than with answers.”

On the other hand, don’t expect the permanent exhibition, at least, to cultivate controversy or to introduce major interpretive dilemmas. Kugelman says the compressed time frame precludes any original research. And Bertz says that deconstructive approaches simply won’t work. “Frankly, in a Jewish Museum, would you want that?” she asks. “In a Jewish Museum, we have to speak with a certain authority. Otherwise, if we would leave everything open to interpretation, we would also have to leave it open to anti-Semitic interpretation, wouldn’t we? In a way, we have to have the authority to say, ‘No, racial theory is wrong, it doesn’t exist, it’s bullshit.’”

Even within these constraints – perhaps necessary ones – the museum has room to challenge its audience. Friedrich says the museum could raise questions about what it means to be German in a society still debating the questions of immigration and citizenship. “We do not need historical museums just for antiquarian reasons and to display the remainders of the material culture,” he says. The museum has “got to play a role within German cultural and political life today.”

But Gorbey is more cautious on this score. “It’s a very interesting question: How far do you get involved in social engineering? I don’t think museums are the right sort of places to actually pump for a particular message…,” he says. “I think museums are much better at touching people’s experiences and getting them thinking more….”

“Obviously,” he adds, “we want people to be tolerant.” He says visitors should see the museum as a place to “understand a bit more about the Jews and Germany, and as a result about other minority cultures and their relationship with dominant cultures….But do I want them to learn to be good? I don’t think I can make that claim.”

©2001 Julia M. Klein

Julia M. Klein is a cultural reporter and critic based in Philadelphia. She is writing a book on the postmodern museum.