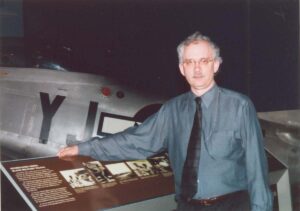

WASHINGTON — Sitting in his book-lined office at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Air and Space Museum, Michael Neufeld talks bitterly about his role as the much-maligned curator of the most infamous museum exhibition never mounted.

“A lot of people in this country don’t want the decision to drop the bomb debated,” he said. “They feel you must obviously be an anti-American evil person even to debate the legitimacy of dropping the bomb…. The fact that there had been 30 years of historiographic debate and development…was irrelevant…. As far as they were concerned, there was a gospel truth: Dropping the bomb prevented the invasion of Japan and ended the war. End of discussion.”

Not so, says John Correll, editor of Air Force Magazine and arguably the person most responsible for stirring opposition to the museum’s planned exhibition on the Enola Gay. In his view, the National Air and Space Museum erred by trying to present a slanted account of the end of World War II that cast the Japanese as victims of American aggression. In talking to the museum, said Correll, “we were astounded at the bias, the close-mindedness, the reluctance to talk, that we ran into…. There was deep resistance to achieving real balance.”

On June 28, 1995, an abbreviated exhibition on the Enola Gay — the B-29 bomber that dropped the first atomic bomb on Japan — did open at the National Air and Space Museum. It featured the forward fuselage and propeller of the plane, a description of the plane’s mission, an account of the plane’s painstaking restoration, and video reminiscences of the men who flew it. Missing, however, was any substantial discussion of either the mission’s historical context or its impact — on the Japanese and the postwar world.

Visitor reaction — recorded in comment cards stored in the Smithsonian archives — was mixed. Many applauded the Smithsonian, the plane and the veterans involved. “This is history,” declared Jeanne Newbery of Memphis, Tenn. “History is history no matter what we feel. We love our servicemen.” Others lamented the gaps left by the exhibition. “You would think from this exhibit that hardly any Japanese lives were lost. SHAMEFUL,” wrote an anonymous skeptic.

Five years later, the story of the original Enola Gay exhibition — an ambitious, if ultimately flawed attempt to capture a charged historical moment — remains a key marker in the evolution of American museums. It vividly illustrates the enormous difficulties involved in translating strongly contested history into the medium of a museum exhibition.

Some who disliked the original 50th anniversary show saw its cancellation as the triumph of “objectivity” over a left-liberal political agenda. But the event’s meaning, like the history of the atom bomb itself, remains contested. To a museum critic, the controversy illuminates the limits of both the notion of objectivity and the use of omniscient third-person narratives in exhibitions. It points the way towards the more complicated, inclusive and self-conscious techniques of the postmodern museum.

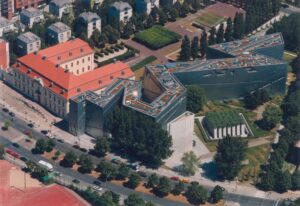

In this new museum, different points of view coexist, and narrative voices compete. History is deconstructed as a fallible human enterprise, and interpretations are seen as a matter of perspective. These techniques, on view in places such as the George Gustav Heye Center of the National Museum of the American Indian in New York, comprise “the new frontier of exhibitions,” said Gretchen Sorin, who heads the Cooperstown graduate program of museum studies. “Exhibitions always had a hard time talking about history from multiple perspectives, and they don’t know how to do it.” But the challenge remains: “How do we teach people that history is not truth, but…depends on the lens through which you’re looking?”

The Jan. 30, 1995 cancellation of the original exhibition followed months of heated press coverage, numerous script revisions and considerable political pressure and posturing. The November 1994 election of a more conservative, Republican-dominated Congress and the installation in September of new Smithsonian secretary, former Berkeley chancellor I. Michael Heyman, helped sound the show’s death knell.

The Smithsonian’s retreat also owed something to sharp divisions within the Air and Space Museum that may have crippled the museum’s ability to mount a coherent defense. By contrast, an energetic public relations campaign by the Air Force Association succeeded in capitalizing on public (and press) misconceptions about history, as well as the Air and Space Museum’s own celebratory heritage.

Appointed by then — Smithsonian Secretary Robert McCormick Adams in 1987, museum director Martin Harwit, an astrophysicist, had a mandate to revamp that heritage. Neufeld said that Harwit seized on the Enola Gay as an instrument of that transformation. Exhibition planners knew early on how explosive their subject matter would be. On July 21, 1993, Tom D. Crouch, then chairman of the museum’s aeronautics department, wrote Harwit a sharp memo in response to concerns voiced by Adams. “Do you want to do an exhibition intended to make veterans feel good, or do you want an exhibition that will lead our visitors to talk about the consequences of the atomic bombing of Japan?” he asked. “Frankly, I don’t think we can do both.”

In his account of the controversy, An Exhibit Denied: Lobbying the History of Enola Gay, Harwit said he had disagreed. “Of course we would honor the men who had been willing to sacrifice so much. How could we not? I saw no reason why realistically exhibiting the Enola Gay had to interfere with that aim.”

Over the next 18 months, neither man would substantially alter his position.

“Martin always felt that he could somehow pull off this mega-exhibit which would make everybody comfortable,” said Neufeld, “and that was a belief that he hung onto to the bitter end…. In fact, with that topic it was much easier to make everybody unhappy than to make everybody happy.”

Neufeld wrote one of the exhibition’s two most contested sections, on the decision to drop the bomb. Seeking to convey disagreement, he highlighted “historical controversies,” including the question of whether Japan might have surrendered without either the dropping of the bomb or a costly U.S. invasion. Crouch wrote the section on the devastation inflicted on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Taken together, the two sections raised the question of whether all that destruction was really necessary.

The first (Jan. 12, 1994) draft of the script, released to Correll’s Air Force Association and widely circulated, was criticized by veterans and others for its emphasis on American racism and the suffering of the Japanese, and especially for a pair of sentences authored by Neufeld: “For most Americans, it was a war of vengeance. For most Japanese, it was a war to defend their unique culture against Western imperialism.” Less tendentious in context, this passage was reiterated in the press long after its excision.

In fact, no matter how much the script changed, the Smithsonian seemed always to be fighting the same perceptual battle. “We started the process in such a hole to begin with,” said J. Michael Fetters, the museum’s assistant director for public relations (now director of marketing and communications for the Newseum in Rosslyn, Va.). “Both the Air Force Association and the American Legion could put central casting veterans on television shows…. And our choices were two curators who were clearly not happy with the way things were going, a director who was slight and had a heavy Czechoslovakian accent, or a 30-year-old PR guy. None of those was an appealing option.”

In response to Correll’s calls for balance, Harwit ordered up an introductory section on “The War in the Pacific” — “a bad idea,” Crouch said. Now a senior curator, Crouch said he believed veterans would never accept any show that honestly illustrated bomb-related destruction in Japan. As a result, beginning in the spring of 1994, he repeatedly suggested to Harwit that the museum back down and simply display the bomber with a few photographs — such as was later done.

“‘This is one we can’t win,” Crouch said he told the director.” ‘If you want to survive this, we really only have one choice, and it’s radical: We fall back to a really small and simple show…. And then we walk away from it.'”

Harwit said he did not specifically recall Crouch’s proposal, but that he was aware of his increasing disillusionment. Still, the director forged ahead.

“If you’re a scientist and you don’t have a particular historical theory that you’re trying to propagate…then you look at these things, I think, with more detachment,” he said. His goal was to stick “very close to the documentation…and then [attempt] not to fall into the trap where overwhelming attention to one set of documents, or pictures or objects would tilt the exhibition to give a point of view that was not justified.”

In the fall of 1994, with the backing of Smithsonian Undersecretary Constance Newman, Harwit and his curators sat down with American Legion officials to try to negotiate an acceptable script, line by line. The ploy was, as Harwit suggests in his book, an attempt to circumvent the more openly critical Air Force Association.

Examination of the amended Aug. 31 script, found in the Smithsonian archives, showed that some changes were stylistic, others more clearly ideological. The phrase “burning Japanese cities to the ground,” for example, became “destroying Japan’s ability to wage war.” In another instance, the line “Truman saw the bomb primarily as a way to end the war and save lives by avoiding a costly invasion of Japan” was stripped of the word “primarily” — a historically resonant omission that ignores the debate about whether Truman was influenced in part by a desire to demonstrate the weapon’s power to the Soviet Union.

Such changes troubled Crouch and Neufeld. “Martin didn’t have any personal commitment to the historical issues involved in this,” said Neufeld. “He didn’t see the endless revision process as a sellout of the original exhibit, and Tom and I did.”

Harwit, Newman and Fetters all say they believed the revisions made the script fairer and better. “But we couldn’t get it above the noise,” Newman said. Whatever the reality, the propaganda battle had already been lost. Newspaper editorials in The Washington Post and elsewhere continued to lambaste the Smithsonian; congressmen were calling for hearings and Harwit’s resignation. Historians and peace activists had been piling on from the left, accusing the museum of purveying “patriotically correct history.” Harwit’s continued tinkering with a controversial section on prospective invasion casualty figures finally gave American Legion officials the excuse they may have been looking for to denounce the show.

Neither a museum expert nor an historian, Heyman said he started his tenure without strong negative feelings towards the exhibition, but “came to feel that a big mistake had been made.” One problem, he said, was “mistiming” — trying to have “a really critically analytic show about the Enola Gay” on the 50th anniversary of the war’s end. Another was in the way the show originally was framed. “The time period it used was making a moral judgment on the use of the bomb,” he said.

Harwit still believes the cancellation could have been prevented by a more adroit defense. Heyman underestimated “his own moral authority,” Harwit said. “I think he was too new at his job at the time, and too eager to please the Congress, and too eager to get this over with and start raising money.”

In Neufeld’s view, Heyman “probably had no choice. Politically, he was completely dead at that point…. Martin Harwit had handed him a political disaster. What did he have to win by standing up for it?” Besides, he said: “It had already been compromised as far as we [he and Crouch] were concerned.”

In the immediate aftermath of the controversy, the National Air and Space Museum, the world’s most visited, suffered a plunge in attendance to below the 7 million mark, Fetters said. It recovered to nearly 10 million in 1998, the highest attendance in a decade.

At the museum, a potentially high-profile show on air power in Vietnam was postponed indefinitely. Edward T. Linenthal, co-editor of History Wars: The Enola Gay and Other Battles for the American Past, said he believed that the battle over the Enola Gay has had a chilling effect on both museums and historians generally, though such assertions are difficult to document.

Others say the impact of the controversy has been more subtle, perhaps even salutary. Spencer Crew, director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, said his museum has learned to solicit diverse perspectives early in the exhibition planning process, to respect the power of memory and to anticipate reactions before they occur. In one case, a long-term exhibition called “Science in American Life” — criticized as too negative — was expanded to show more of science’s positive effects.

“I think what we’re trying to do is get away from the idea that there is a single truth, a single history for anything,” Crew said. “History is a rich layer of information, and how you can begin to understand it depends on how you link together those pieces of information, and what perspective you have on it.” A new exhibition, “American Legacies,” will emphasize that “interpretation of objects can vary” and “demystify…what goes on in museums. “

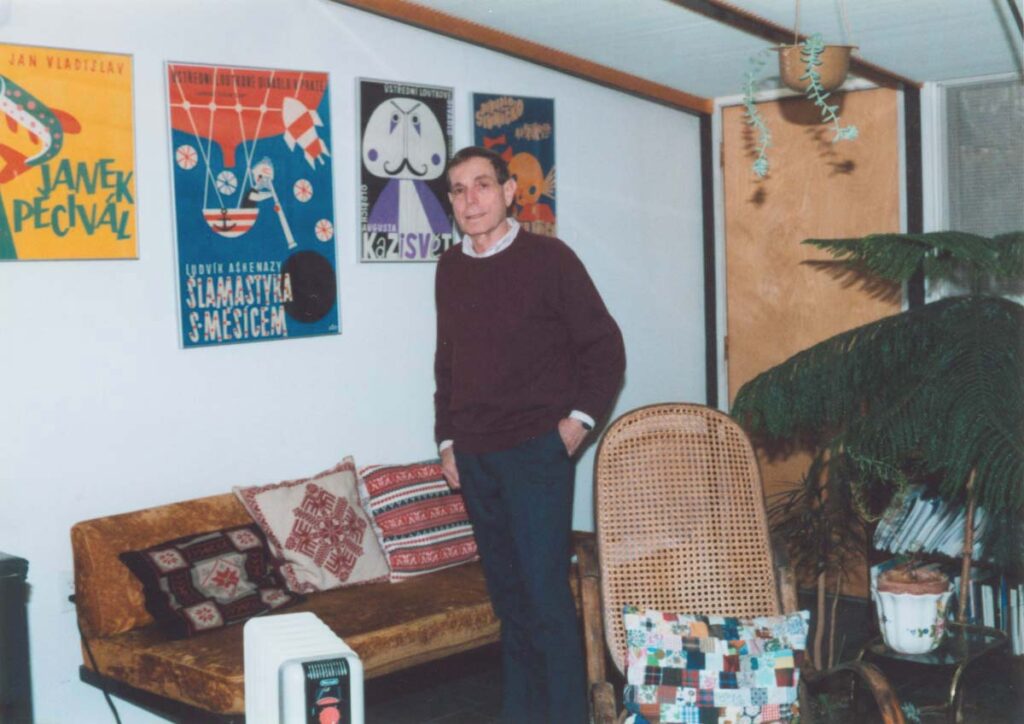

All of the players in the controversy were affected by it, but the personal fallout was greatest for Harwit, now 69, who was forced to resign from his post in May 1995. Despite submitting some 50 job applications, he says, he never found another job. He now works as a freelance astrophysicist.

The exhibition still haunts him. Framed prints of cartoon commentary on the show fills his airy townhouse. He owns a video of the Enola Gay crew’s reminiscences that was to have been the exhibition’s coda. He helped archive the voluminous paper trail generated by the show to document it for posterity.

“I thought that…perhaps 25 or 50 years from now, somebody would want to redo that exhibition,” he said wistfully. “I thought I’d like people — to see this and decide then whether this was a reasonable way to portray this historic event.”

©2002 Julia M. Klein

Julia M. Klein is a cultural reporter and critic based in Philadelphia. She is writing a book on the postmodern museum.