Forget the crappy caregiver bots and puppy-eyed seals. When my parents got sick, I turned to a new generation of roboticists—and their glowing, talking, blobby creations.

This article first appeared in the January, 2024 edition of Wired. Her research was supported by an Alicia Patterson Foundation grant.

When my mom was finally, officially diagnosed with dementia in 2020, her geriatric psychiatrist told me that there was no effective treatment. The best thing to do was to keep her physically, intellectually, and socially engaged every day for the rest of her life. Oh, OK. No biggie. The doc was telling me that medicine was done with us. My mother’s fate was now in our hands.

My sister and I had already figured out that my father also had dementia; he had become shouty and impulsive, and his short-term memory had vaporized. We didn’t even bother getting him diagnosed. She had dementia. He had dementia. We—my family—would make this journey solo.

I bought stacks of self-help books, watched hours of webinars, pestered social workers. The resources focused on the basics: safety, food, preventing falls, safety, and safety. They all hit the same tragic tone. Dementia was hopeless, they said. The worst possible fate. A black hole devouring selfhood.

That’s what I heard and read, but it’s not what I saw. Yes, my parents were losing judgment and memory. But in other ways they were very much themselves. Mom still reads the newspaper with her pen, annotating “Bullshit!” in the margins; Dad still asks me when I’m going to write a book and whether I need cash to get home. They still laugh at the same jokes. They still smell the same.

Beyond physical comfort, my goal as their caregiver was to help them to feel like themselves, even as that self evolved. I vowed to help them live their remaining years with joy and meaning. That’s not so much a matter of medicine as it is a concern of the heart and spirit. I couldn’t figure this part out on my own, and everyone I talked to thought it was a weird thing to worry about.

Until I found the robot-makers.

I’m not talking about the people building machines to help someone put on their pants. Or electronic Karens that monitor an old person’s behavior then “correct” for mistakes, like a bossy Alexa: “Good afternoon! You haven’t taken your medicine yet.” Or gadgets with touchscreens that can be hard for old people to use. Those kinds of projects don’t work. They’re clunky or creepy. More to the point, they rarely fulfill a real need. They’re well-meaning products of black-hole thinking.

Instead, the roboticists I learned about are trained in anthropology, psychology, design, and other human-centric fields. They partner with people with dementia, who do not want robots to solve the alleged problem of being old. They want technology for joy and for flourishing, even as they near the end of life. Among the people I met were Indiana University Bloomington roboticist Selma Šabanović, who is developing a robot to bring more meaning into life, while in the Netherlands, Eindhoven University of Technology’s Rens Brankaert is creating warm technology to enhance human connection. These technologists in turn introduced me to grassroots dementia activists who are shaking off the doom loops of despair.

The robot-makers are a shaft of light at the bottom of the well. The gizmos they’re working on may be far in the future, but these scientists and engineers are already inventing something more important: a new attitude about dementia. They look head-on at this human experience and see creative opportunities, new ways to connect, new ways to have fun. And, of course, they have cool robots. Lots and lots of robots. With those machines, they’re trying to answer the question I’m obsessed with: What could a good life with dementia look like?

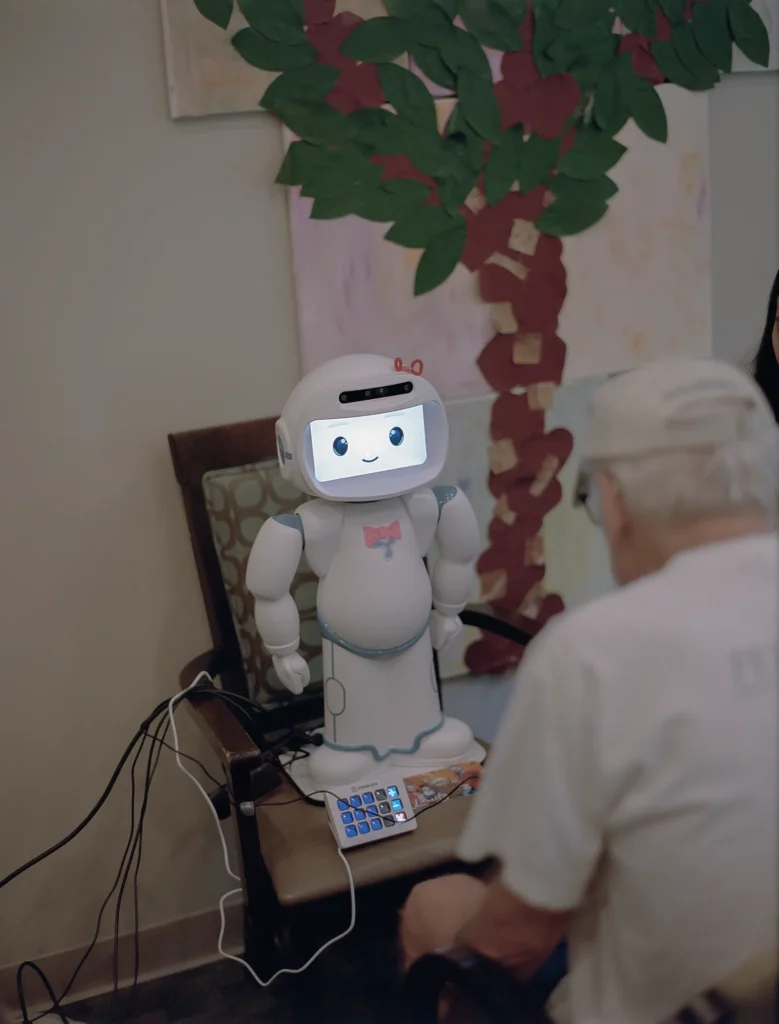

The robot’s torso and limbs are chubby and white. It seems to be naked except for blue briefs below its pot belly, although it does not have nipples. It is only 2 feet tall. Its face, a rectangular screen, blinks on. Two black ovals and a manga smile appear.“Hello! I am QT, your robot friend,” it says. It says this to everyone, because that’s its job. QT raises both arms in a touchdown gesture. The motors whir. They sound expensive.

It might look and sound sort of familiar if you know anything about humanoid social robots—contraptions built to respond to us in ways we recognize. You may also remember their long history of market failures. RIP Kuri, Cozmo, Asimo, Jibo, Pepper, and the rest of their expensive, overpromising metal kin. QT is not like them. It is not a consumer product; it’s a research device equipped with microphones, a 3D camera, face recognition, and data recording capabilities, built by a Luxembourgian company for scientists like Šabanović to deploy in studies. She’s using QT to explore ikigai, a Japanese word that roughly translates to a reason for living or sense of meaning in life, but also includes a feeling of social purpose and everyday joy. Doing a favor for a neighbor can create ikigai, as can a hard week’s work. Even reflecting on life achievements can bring it on. Her team, funded by Toyota Research Institute, is tinkering with QT to see what kind of robot socializing—reminiscing, maybe, or planning activities, or perhaps just a certain line of conversation—might give someone a burst of that good feeling.

To see QT in action, I drive Šabanović and graduate student Long-Jing Hsu over to Jill’s House, a small memory care home in Bloomington less than 2 miles from the university. Šabanović and her teams of students and collaborators have worked alongside residents here for years. It’s now September, and all summer Hsu has visited every week, leading workshops, testing small adjustments to QT’s demeanor and functionality, collecting data on how people react to the robot—whether they smile, mirror its gestures, volunteer parts of their life story, or get bored and annoyed. Making decisions about how and what the robot should do is not up to the researchers, says Šabanović. “It’s up to this deliberative, participatory process, and engaging more people in the conversation.”

Today, Hsu will demo a storytelling game between person and machine. Eventually QT will retain enough information to make the game personalized for each participant. For now, the point is to test QT’s evolving conversational skills to see what behaviors and responses people will accept from a robot and which come across as confusing or rude. I’m excited to see how this plays out. I’m expecting spicy reactions. People with dementia can be a tough audience, with little tolerance for encounters that are annoying or hard to understand.

After I park the car, we enter a large common room with cathedral ceilings and high windows, bright with sunlight. As we chat with the director, Hsu crosses at the back, a small figure pushing a white robot on a cart past the wingback chairs and overstuffed love seats to a small side conference room. It’s a spectacle, but the residents who are hanging out this afternoon take little note. To them, robots are old news.

We follow her into the side room and pull chairs into a semicircle around the robot on his table. Šabanović will mostly just watch today as Hsu troubleshoots the tech and leads the session. Soon, Maryellen, an energetic woman in a red IU ball cap, walks in and takes a seat across from the robot. Maryellen has enjoyed talking to QT in the past, but she’s having an off day. She’s nervous. “I’m in early Alzheimer’s, so sometimes I get things wrong,” she apologizes.

The robot asks her to select an image from a tablet and make up a story. Maryellen gamely plays along, spinning a tale: A woman, maybe a student, walks alone in the autumn woods.

“Interesting,” says QT. “Have you experienced something like this before?”

“I have,” Maryellen says. “We have beautiful trees around Bloomington.” The robot stays silent, a smile plastered across its screen. QT has terrible timing, pausing too long when it should speak, interrupting when it should listen. We all share an apologetic laugh over the machine’s bad manners. Maryellen is patient, speaking to QT as if it were a dim-witted child. She understands that the robot is not trying to be a jerk.

Today’s robot-human chat is objectively dull, but it also feels like a breath of fresh air. Everyone in this room takes Maryellen seriously. Instead of dismissing her pauses and uncertainty as symptoms, the scientists pay careful attention to what she says and does.Next enters Phil, a man with a tidy brush mustache, neatly dressed in chinos and a short-sleeve button-down printed with vintage cars. After taking a seat across from the robot, he chimes in with QT to sing “Take Me Out to the Ball Game.” He faces the machine, but he’s playing to us, mugging and rolling his eyes. Song over, he first teases Hsu, then another resident, then pretty much every woman in the room. In other circumstances he’d be patronized or “diverted”—someone would attempt to distract him. Instead, we join him in being silly, joking about the situation and the robot.

QT pipes up with another round of awkward conversation (“I love the song. Do you?”), and Phil replies with a combination of graciousness and sass (“You sing very well. Did you have that recorded, maaaybe?”). Hsu asks Phil how he felt talking to the machine. “Like I’m a fool talking to nothing,” he says sharply. “I know it’s not a real person.” Theatrically, he turns to the robot. “You’re not real … are you?” He winks, and laughs uproariously.

The R-House Lab at Bloomington seems to be an ordinary conference room: white walls, large wood conference table, and desks, chairs, and monitors ringing the walls. But it is littered with the artifacts of Selma Šabanović’s research career, a menagerie of robots and robot parts. Perched on a windowsill are two butter-yellow Keepon units, an early invention that’s little more than two spheres with eyes and a button nose. A fluffy white seal named Paro recharges on a filing cabinet, its power supply a pink pacifier plugged in where its mouth should be. In the back of the room lurk two of Honda’s 2018 Haru, something like a desk lamp crossed with a crab. Three more QTs (2017) doze on tables. It’s like an unnatural history museum, and Šabanović is the resident David Attenborough.

Šabanović, 46, is tall and slender with a cloud of dark hair and an aura of sly humor that suits this strange place. Now she sits at the back of the room as her team hashes out ways to solve QT’s social problems. At one point, the students get stuck on QT’s habit of interrupting. Maybe that’s OK, Šabanović proposes. “We can play off the fact that it will be, inevitably, to some degree, stupid,” she suggests. What the researchers need to figure out is “where stupidity is harmful.”

She may be in her element, but the defunct and sleeping robots give the room a weird energy, as if it were full of ghosts. This, I learn, is the superpower of social robots: not strength, not speed or precision, but vibes. They grab hold of our psyche. They get under our skin. Even though we know better, we respond to them as if they were alive. The tech critic and author Sherry Turkle calls it pushing people’s “Darwinian buttons.” Unlike most other gadgets, robots get our social instincts tingling. Of course, explains Šabanović, “what distinguishes robots is that they have a body.” She adds, “They can move, show they’re paying attention, trigger us.” Children learn more from a robot than a screen. Adults trust robots more readily than computers. Dogs obey their commands.

Šabanović is fascinated by these reactions, which makes sense, because she has lived her life in the company of robots. Her parents were both engineers, and her father worked on industrial robots. Back in those years, the only social robots were in fiction. Her father’s contraptions were serious machines for heavy industry. When she was 9, in 1987, the family spent a summer in Yokohama. An only child, she would often tag along to work and curl up in the lab with a book. In Japan, she noticed, fictional robots were friendly and helpful: more Astro Boy than Terminator. In college in the mid to late ’90s, she puzzled over those differences and wondered why some cultures assumed future robots would be sweet and cute, while others imagined them as villains or thugs.

By then she was also dropping in at conferences with her parents, where she heard about real social robots—machines designed to interact with humans on our terms. This seemed like a strange idea. The industrial robots she knew so well were unattractive and untouchable, doing dangerous tasks on assembly lines. “It was super intriguing to me—how do they think this is going to work?” she says.

She wanted to understand these new relationships forming between people and machines. In graduate school, she visited and observed the people who were developing the field of social robotics. In 2005 she spent time with the pioneering roboticist Takanori Shibata at Japan’s National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology and his robot seal pup Paro. Handcrafted, the little critter responded to speech and touch by bleating—it was programmed with actual seal pup cries—closing its eyes, and flipping its tail and flippers. It was one of very few robots at the time that could be used outside the lab without expert assistance.

Even at this early stage, elderly people were the target audience. The researchers took the machine to care homes, and Šabanović was startled to see the effect. “People would suddenly light up, start talking to it, tell you stories about their life,” she says. Shibata’s studies, then and later, showed that the cuddly seal improved quality of life; it got people to interact more, reduced stress, and eased depression.

So Šabanović joined the emerging field of human-robot interaction. Her experiments since have explored how we project our “techno-scientific imaginaries”—our cultural baggage, fears, and fantasies—onto these hunks of metal and plastic. Sort of like if Isaac Asimov became an experimental psychologist.

In one early study, she brought Paro into a nursing home to study how the device turned wallflowers into butterflies. Most residents would ignore the seal pup until other people showed up—then it would become an icebreaker or a social lure. They’d gather to touch it. They’d comment on its sounds and movements, laughing. The robot, she saw, seemed to open a door to other people.

Starting in the 2010s, with new machines like Haru and the android Nao, which had more features and data-collecting capacity, she has explored ways to bring more kinds of people into the creative process. Since then, Šabanović has cowritten a textbook on human-robot interactions and examined dynamics among children, robots, and groups of people. During my visit, Šabanović’s group was preparing to bring QT out to meet the public for the first time at the annual conference of the Dementia Action Alliance in Indianapolis. Unlike most meetings about brain diseases, this one has no sessions about new drugs and no pharma-funded cocktail hours. Also unlike other conferences, it includes a lot of people who have dementia. Its purpose is to foster community and share knowledge, but as I’d learn, it’s also a coalition of people who are fed up with shame and stigma and are starting to insist on something better. I was about to meet people who not only could bear the diagnosis with hope, but embrace it.

The Indianapolis Crowne Plaza hotel was built as a Gilded Age train station, and the conference exhibition hall is a former waiting area, its tiled hallways now echoing with the chatter of people filling the room. Most people drift by without pausing to inspect the robots perched on the table in front of Weslie Khoo, a postdoctoral researcher in computer vision who is in charge of the machines today. Then Diana Pagan makes a beeline for Paro, the little white seal. She strokes it as it flips its tail and slowly blinks its huge black eyes. She’s thoroughly charmed. It’s relatable, she says. “It’s more real to me. Whereas that thing,” gesturing at QT, “is … a machine.”

Her middle-aged son John-Richard Pagan is curious about QT. But he’s prone to hallucinations, he says, and would not want a talking robot in his home. “A voice coming out of the box would be disturbing,” he says. John-Richard has Lewy body dementia, which can cause confusion and problems with attention. He is also a self-proclaimed techie and a bit of an early adopter. Back in the day, he had a Commodore 64, an early mass-produced home computer. Now he’s part of a technology working group organized by the Dementia Action Alliance. He seems to be a robot kind of guy on paper, but in general, robots fail his tests. Most inventors don’t get it, he says. Anything for people with dementia has to be intuitive. You can’t assume someone’s around to explain how to use it. It has to be affordable, because many people with dementia are on fixed incomes. And it would need to be flexible and personalizable.

John-Richard would like a machine that can recognize when he is having a bad day—maybe it analyzes his speech patterns and tells him to rest, or perhaps it plays music. Maybe it talks to him softly when it hears him scream in his sleep from dementia–induced night terrors and tells him he’s OK, that he’s not alone. “Wherever I’m at, it hears me and acknowledges me,” he says. “It works with my flow.”

Over the next few days of the conference, people share stories of what dementia is like, swap tips to make life easier, and talk about hardships and good times. It feels like a family get-together. Instead of black holes, these narratives are bittersweet mixtures of loss and discovery. One speaker says he can’t balance his checkbook anymore, although he once was an accountant. But he fell in love with photography, and his creative life is flourishing.

During a presentation, Šabanović asks the audience how a home robot might make their lives better. She listens, stroking Paro, and the conversation inevitably turns toward the ick factor. A robot animal that talks is dehumanizing, says one woman with dementia. “I see the opposite,” says another, elaborating: If it makes someone happy, why should others judge?

Hearing people with dementia debate these ethics themselves, it is obvious that they should have led this conversation all along. The discussion should be one of thousands on who is entitled to not only life but also self-fulfillment and self-definition.

The roboticists I talk to all point to an influential paper by Amanda Lazar, a professor of human-computer interaction at the University of Maryland. Lazar described in 2017 how the field of human-computer interaction might learn from new thinking about dementia and the mind. Going way back to René Descartes, human cognition has conventionally been defined around the capacity to reason, to speak, to remember. Those definitions exclude many people with dementia, and, Lazar argued, they also limit our imagination about what computers and robots can be. In more recent decades, cognitive scientists have explored and considered human capacities like mind-body connections, sensory experiences, and emotions, which can be intact or even heightened in dementia. Perhaps, Lazar suggests, our vision of tech could expand in parallel, away from purely cognitive prosthetics and toward a more holistic appreciation of mental function.

Her formulation is aimed at other scholars, but it ricochets around my brain. My parents don’t remember. They live vividly in the moment—cracking jokes, noticing tiny details of my clothing or hair, constantly surprising me with their strong opinions. Both are newly fascinated by the constant traffic in their California suburb. “Look at all the cars!” my mother says to me, or my father says to my mother, in wonder mixed with horror. They teach me that imagination and creativity persist in the human brain long after memory and logic break down. “It’s like a wool bathing suit,” said my dad out of the blue at dinner one night, pointing to his face. Eventually I realize that he was telling me his beard was getting itchy and needed trimming.

They would have no idea how to deal with QT and its cheerful Q&A; this ikigai project is not designed for people whose language is starting to fracture. But other inventors have people like them in mind, Lazar told me over Zoom. In the Netherlands, in Belgium, and in the UK, a weirder wave of robot development is venturing into the uncharted world of advanced dementia, finding untapped possibilities for play and delight, creating robots for the soul.

A pair of round, white blobs sit side by side, each the size and shape of a pumpkin. Every 10 minutes or so, the orbs croak like frogs, or chirp like crickets, and sparkle with light. They want your attention. Pick one up, and depending on whether you stroke it, tap it, or shake it, it will respond with noise and light. If the orbs are set to “spring” mode, and you stroke one, it will sing like a bird and blush from white to pink. If you ignore the second blob, it will act jealous, flushing red. If your friend then picks up orb number two, they will mimic each other’s light and sound, encouraging you to play together.

The blobs are called Sam, and together they form a social robot boiled down to its essence: an invitation to connect. Sam is one of the otherworldly creations emerging from the Dementia and Technology Expertise Centre at the Eindhoven University of Technology in the Netherlands. Rens Brankaert and his colleagues don’t call this—or the other things they make—a robot. They call it warm technology. “We want to contribute to the warmth between people,” he says. And to create gadgets that a wider range of people would enjoy using.

The approach is shaped by Brankaert’s own history in design. As a student, he built a large, easy-to-read interactive calendar for people with cognitive impairment. Users could create daily schedules and reminders by clipping drawings of pills, a telephone, or food into place at the appropriate hour. He brought the prototype around to people’s houses, only to find they hated it. They saw it as the equivalent of a wheelchair or cane, a symbol of impairment, or what one advocate dubbed a “disability dongle”—a well-intentioned gadget that doesn’t solve a real problem. Brankaert’s mistake was one many designers make: He didn’t ask his audience what they wanted.

This experience set him off on a PhD, and on a journey to figure out how to work collaboratively with people at all stages of dementia. Every Wednesday afternoon, Brankaert and his students meet with a local group of people with mild dementia—a partnership that, like Šabanović’s collaborations, has gone on for years. The designers also work on projects in a nearby care home, with residents whose gestures, flickers of interest, laughter, and uses of metaphor can be as meaningful as their words. While exploring an early proto-type of a sound-making device, one introverted woman reacted to birdsong by imitating the motion of wings with her hands. “I sometimes get a little bit of jitters, so I go up there, with all those birds,” she said, smiling. “I just love it! How everything flies up there!” Another person pretended to release pigeons.

It’s what Lazar was talking about: tech that meets us where we live with sensations and experiences rather than mediated by texts and swipes. Often, these inventions are pleasantly surreal. Cathy Treadaway of Cardiff Metropolitan University in the UK designed Hug, a floppy fabric machine, kind of like a heavy human-shaped scarf. Wrap its arms around you, and the “heart” within begins to thump—for wordless comfort.

My mom can be so present in the moment that she seems to be almost outside of time. From my perspective, this immediacy looks like it could be a relief, perhaps a saving grace of her dementia. But I really don’t know. Sharing the experience of one of these gadgets might help me join her in her reality instead of always trying to drag her back into mine. Why not a scarf with a beating heart? Why not glowing friend-blobs?

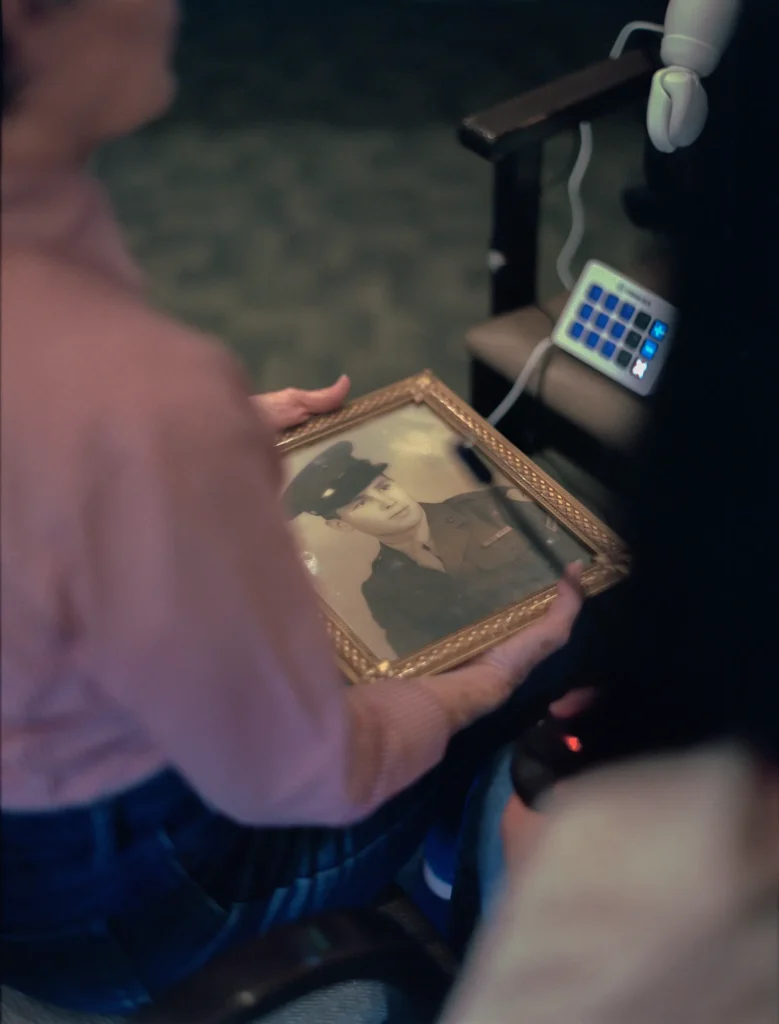

One of the warmest technologies from the Eindhoven group and their collaborators is Vita, a patchwork pillow with vinyl panels. Pass your hand over a patch and a sensor detects your presence, playing a personalized, familiar soundscape: a stroll down a cobblestoned street in the rain, maybe, or the clatter of coffee cups and servers and spoons at a café. Family members and caregivers select the sounds they think will resonate with the user. Over years of testing, the pillow has been fine-tuned, and Brankaert is currently talking to a partner to produce it and bring it to market.

In one demonstration, a white-haired woman sits quietly, looking dreamy, or very possibly sleepy. “Good morning,” says her daughter, but the woman does not respond. The daughter places the pillow on her mother’s lap and guides her mother’s hand over a large yellow patch. The chorus of the World War II chestnut “We’ll Meet Again” emerges. The older woman’s eyes brighten, and a smile of recognition creeps over her face. She begins to sing.

What is this pillow gadget for? It doesn’t restore her speech or fix her memory or replace anything she no longer can do. It helps the two of them find each other again across the dim and confusing terrain of dementia.

It’s December when I revisit Šabanović’s lab, this time by videoconference, aided by a telepresence robot named Kubi. The device is basically a tablet on a motorized stand that the remote user—me—can rotate to face others in the room (Kubi means “neck” in Japanese). I launch the app and see Hsu, who has carefully placed the system on the conference table. Around me are a group of older people with and without dementia who are invited here each month to analyze ongoing projects. Today they’re once again evaluating QT. The robot demonstrates a few new skills, and they rip into its performance enthusiastically and with precision, zeroing in on its ineptitude with basic signals of conversation, like understanding whether someone has merely paused or actually stopped speaking.

You learn a lot about people by hanging out with robots. QT made it plain to me how much human interaction depends on tiny movements and subtle changes in timing. Even when armed with the latest artificial intelligence language models, QT can’t play the social game. Its face expresses emotion, it understands words and spits out sentences, and it “volleys,” following up your answer with another question. Still, I give it a D+. My parents, meanwhile, have no problem picking up on conversational nuances. My mother now speaks less, but even as she recedes from the world and spends more time absorbed in her own thoughts, she is quick to gauge my emotions and intentions. I can lie to her with words, but I cannot hide my feelings. She knows.

When I started talking to people like Šabanović and Brankaert, I didn’t understand how they could see the humanity in dementia so clearly when dementia experts often can’t. Now I think I have an answer. To create successful interactive technology, you need an operational understanding of humanness: what’s not enough, what’s too much, and the factors that shape this judgment. Gauge this correctly and your robot is cute, useful, or impressive; do it wrong and your robot is a creep. These robot-makers aren’t preoccupied by what’s missing in people with dementia. They see what endures and aim directly for it.

Predictions about dementia are daunting. Every year, more of us—and more of our parents, friends, and loved ones—will live with it. Millions more will be called on to help, just like me. But the robot–makers have revealed to me that caregiving and dementia don’t have to be the miserable domains of adult diapers, decline, and despair. Helping my parents is still the hardest job I’ve ever had. I stumble over and over again, failing to anticipate their needs, failing to see what has changed and what hasn’t. It’s agonizing. But it can be beautiful, gratifying, and even fun. For now, there’s no shiny new pal that will fix my parents’ lives. That’s OK. I found something better: optimism that people with dementia and their caregivers won’t be so alone.

It’s four days before Christmas, and QT is visiting Jill’s House again, decked out in a Santa hat and a forest-green pinny for this visit. With the help of ChatGPT, QT is now more fun to talk to. A few dozen residents, family members, and staff are here, plus much of Šabanović’s team. Šabanović’s 3-year-old daughter, Nora, is nestled on her lap, carrying on the family legacy. She stares shyly at the robot.

This is a holiday party rather than a formal experiment. The session soon devolves into friendly chaos, everyone talking over one another and laughing. We all chime in to sing “Here Comes Santa Claus,” the robot flapping its arms. Phil plays peek-aboo with Nora. It really does feel like a glimpse of the future—the people with dementia as just regular people, and the machine among the humans as just another guest.

© 2024 Kat McGowan

Kat McGowan’s research was supported by an Alicia Patterson Foundation grant. This article first appeared in the January, 2024 edition of Wired.