WESTLEY, California – Just as farmwork has changed, so has care for children of those who work in America’s fields. Head Start, for migrant farmworkers’ children, follows their parents’ seasons on the soil.

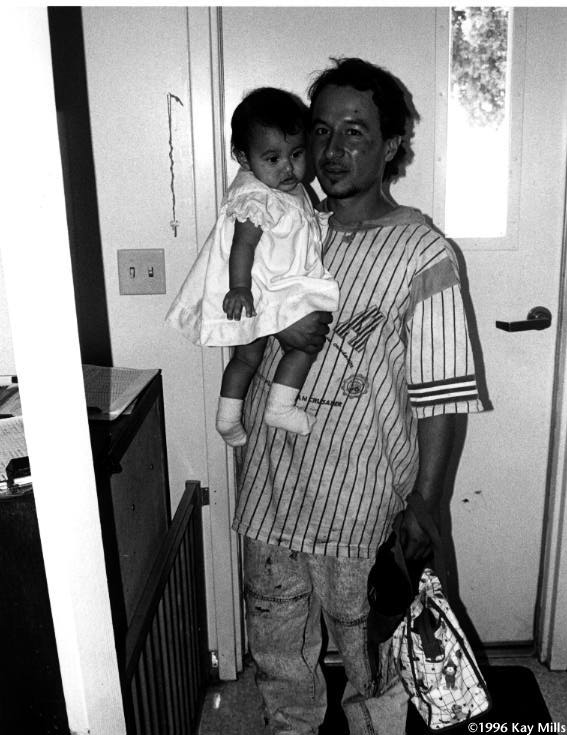

Farmworkers often move less frequently today because they have better housing (better, but not always good). They no longer have to take their youngsters into the fields or leave them in their cars, under a shade tree where possible. Now they start arriving at 5 a.m. at the Head Start program in the migrant housing camp at Westley in the rural San Joaquin Valley, or at scores of other centers wherever crops are being picked. Across the country, for example, parents drop their children at the Head Start at St. Paul’s Lutheran Church in Biglerville, Pa., before heading out to harvest apples or peaches.

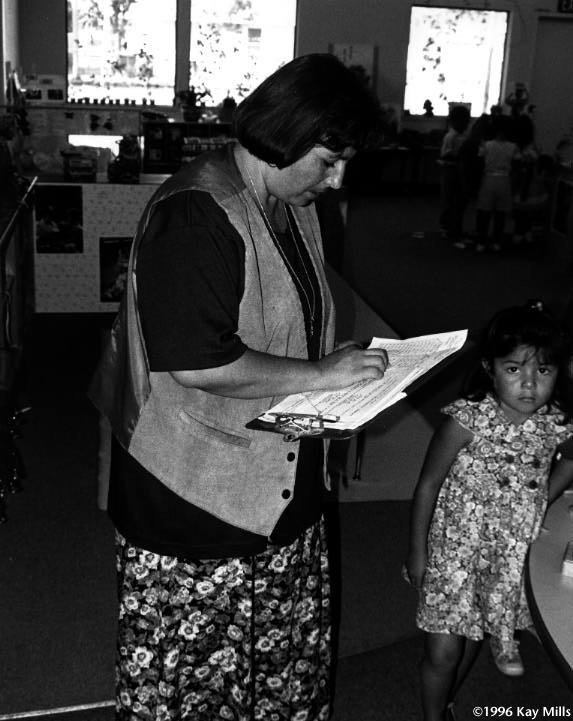

Head Start has as its mission helping young children gain skills they will need to succeed in school, providing health screenings and inoculations, feeding the youngsters nutritious meals and teaching them to brush their teeth after they eat, as well as involving their parents in their educations.

Families qualify for Head Start depending on their income. For example, if a family of four earned $15,150 or less a year, the children could enroll in Head Start. Migrant Head Start programs have the same mission but differ from most others in several key ways.

- Parents must have moved within the previous 12 months and must make their living from agricultural work. To qualify for infant and toddler care, both parents must be working. “There’s not one family we have that’s on welfare,” said Jane Nutter, a deputy director of the agency running the Biglerville program. “They are families – nuclear families – mom and dad – together raising their children. I bet I could count on my hand the number of single parents in our program.”

- Head Start programs usually follow the regular school year. Often children attend for half the day. Migrant Head Start programs open when the families arrive in an area. For example, the Westley center generally opens in April and runs through November or early December as parents pick apricots, then tomatoes, and later walnuts and almonds. The Biglerville program opens in late July and runs into November. Centers open before dawn and don’t close until the parents return from the fields or the orchards in late afternoon.

- Nationwide, the bulk of Head Start students are three-and four-year-olds. Migrant Head Start, however, cares for children from six weeks up to school age. Migrant programs thus need more teachers and aides because the ratio of staff to infants is one to three, where in classrooms for older children it’s one to eight. Westley, for example, had 90 infants and toddlers under three-years-old at the peak of the 1995 season; nearly three-fourths of Biglerville’s total enrollment was infants and toddlers.

- On the West Coast, migrant Head Start programs are operated regionally whereas one agency – the East Coast Migrant Head Start Project – oversees programs from Florida to Maine, delegating the actual center operation to agencies like Rural Opportunities, Inc., a private non-profit corporation that this year serves about 896 children in Pennsylvania, Ohio, and New Jersey. In California, the Westley center is part of the Stanislaus County Child and Infant Care Association, one of the agencies that runs migrant Head Start in a seven-county central California regional program.

- With one umbrella agency supervising all the East Coast migrant programs, staff members work to pass children’s records from center to center during the season and to provide some continuity in the activities that help children develop their skills. In California, however, Hal DeArmond, director of the seven-county regional migrant Head Start program headquartered in Modesto, says that transferring the records there hasn’t worked. One year, the program got records back from only two of nearly 800 parents that had been given them the previous year – even though 70% of the families come back to the same area. “After four years of that, we just had to stop.”

Children of migrant workers bring with them the needs of any youngsters who move frequently – either medical problems because parents had no access to health care or no time to tend to children’s infections, or emotional uncertainties.

Ismelda Cantu, the Westley center supervisor, knows about the need to help children prepare themselves for moving often. Her family, which spent each winter in McAllen, Texas, followed the crops into Illinois, Colorado or California until she was eleven. “I remember we’d go into a school and be there maybe two days. There was no work and we had to move out.” In other places, “you’d finally make a friend and then you’d be gone.”

Cantu, the seventh of 13 children, dropped out of school in tenth grade to help support her family. She weeded crops and rode the hot, dusty machines that pick tomatoes, plant and all, for workers to clean and sort before the tomatoes are conveyed into trailer trucks traveling alongside through the fields. Cantu married at 18 and had a daughter, whom she enrolled in Head Start. She started to volunteer for the program, “probably because I didn’t want to let go,” she said.

Soon she started substituting as an aide for the program and became motivated to earn her high school diploma. Now she’s only a few courses shy of receiving her A.A. degree from Modesto Junior College and hopes to attend California State University Stanislaus in nearly Turlock. “My life was in the fields, ” she said. ” My parents had maybe a fifth grade education. They didn’t discourage education but they never encouraged it. For us, making a living, putting food on the table, surviving, was more important.”

One of the Head Start staff who encouraged Cantu – sometimes prodding her to do jobs she feared she couldn’t do – was Pearlene Reese, formerly the Westley center supervisor and now the executive director of the Stanislaus County Child and Infant Care Association. Reese is another of the adults whose lives were changed by Head Start, a phenomenon well known within the program but unheralded outside.

The oldest of eight children, Reese came with her family to the little agricultural town of Dos Palos in Merced County in the 1930s. Her father had ridden a freight train from Arkansas to see whether he could find work. “Cotton is king over that way,” Reese said, and she dropped out of school in tenth grade to work in the fields.

“In 1965, Head Start came to town. We had never heard of anything like this before. We thought it was almost too good to be true. It was going to provide all these services for children. And there were no jobs in this little town. I was 32 and never had had a year-round job at that point.”

She applied to be a community aide because she felt she had no skills and couldn’t be a teacher. The superintendent of schools, who sat in on all the job interviews, thought she had promise. She could be an instructional aide, he said – only on the condition that she go back to school. “There’s not a choice,” he told her.

Reese took classes in child development, finished junior college, then got a B.A. from what was then Stanislaus State and in 1986 earned a master’s degree in education from California State University Sacramento. Often she would work from early in the morning at Westley, then drive either to Turlock or eighty miles each way to Sacramento to take evening classes. “I had the feeling that someone could see something in me that no one else had. At home I just helped with the work. I was the oldest and I was just the workhorse. You didn’t get a lot of strokes. You just did what you did. Head Start let you try to stand on your own and was there to support you.”

Head Start encouraged the parents of Dos Palos to get involved and, in tending to their own children’s needs, they realized that the community needed running water so the youngsters could take baths. Churches got involved in the program, too. “If Head Start never came,” Reese said, “I don’t know where my life would have gone. More than what it did for the children, it’s what it did for the adults.”

Turnover among teachers in Head Start is high because of low pay. A beginning Head Start teacher in the Stanislaus program earns $8.50 an hour for an eight-hour day. Teachers can count on working about 165 to 170 days a season, which translates into $11,220 a year. Reese estimated that her program loses about 25% of its staff each year. Now that she can offer them health, dental and life insurance – but still no retirement benefits – she can retain some of the more qualified people.

“But we often don’t attract the caliber we need because migrant Head Start still is not viewed as mainstreamWe are the stepchild of the child development community. The families you serve don’t have any status, so you don’t. There’s not a lot of value placed on what we do.” Head Start often must train its own staff. Working through Modesto Junior College and helped by funds from the state, Head Start teachers can receive money to cover tuition and books for some classes they need. In addition, the Stanislaus County Office of Education, which oversees the seven-county migrant program, offers intensive teacher training twice a week.

Norma Gonzalez and Jeanine Ferreira, both aides at the Los Banos center, have taken the training. Gonzalez, who is 19 and ultimately wants to be a counselor, said the training helped her both in dealing with parents and in understanding the children. With infants and toddlers, she said, they can’t tell you what they feel so “every clue they give you, you have to keep in mind.”

Three of the Stanislaus County centers have also been selected to help provide training for teachers from migrant Head Start programs around the country. Teachers and directors come for a week at a time. After an assessment of what they need to work on, they observe classrooms through one-way mirrors and with audio headsets and confer with mentors like LaVonda Estep, who runs the Walter Thompson Center in Ceres, a community just outside Modesto.

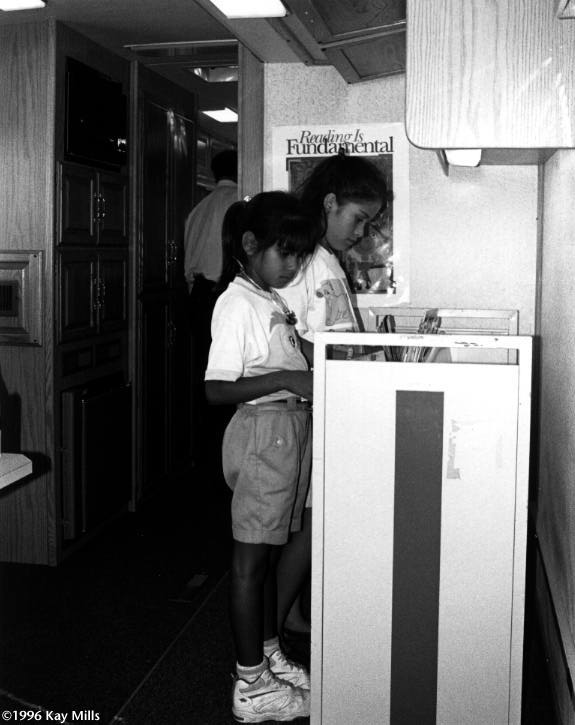

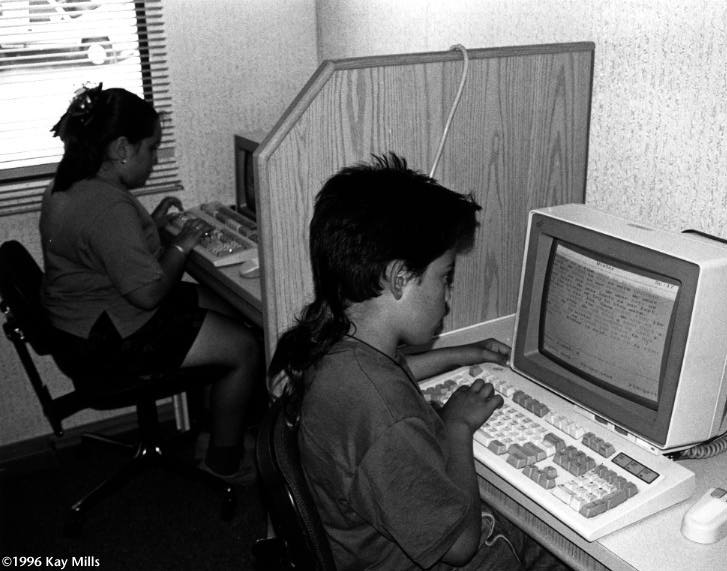

The regional program also offers literacy training for parents and older children. Several days each week Anthony Butera wheels the “literacy van” – a Winnebago with books for children and parents and four computers on board – down the valley’s backroads to Head Start centers. One afternoon in Los Banos, several parents came with their youngsters to borrow books while Allan Espinoza and other older children worked on reading comprehension and sentence structure on the two IBM and two Macintosh computers in the rear of the van.

Butera, a literacy specialist, said his fond dream is to get an encyclopedia on CD-ROM for the young people to use.

It’s clear from looking at the housing in Los Banos – it’s perhaps 20 feet by 10 feet, just big enough for sleeping and some cooking – that no one has any encyclopedias. There’s no handy library, yet children often have school assignments for which reference materials would be helpful.

In another approach to literacy, Juan Lezama, who runs the Merced Migrant Head Start Services, has started a program to teach illiterate parents to read and write in Spanish so that they can then learn English. “I saw that some of them had trouble even filling out our forms. They had either no education in Mexico or second or third grade educations.” Lezama’s program works in cooperation with the Mexican government and provides both basic literacy training or secondary school work for parents working toward high-school equivalency diplomas.

One of the teachers in the Merced literacy program is Miriam Ortega, whose daughter, Jahdaiz, graduated in August from Head Start in the Planada migrant labor camp outside Merced and started kindergarten. Ortega, who was encouraged to become active by Planada’s social worker, Mary “Sukie” Contreras, has been president of the local and regional parent policy councils. She has also enrolled in college in Blythe, California, where her family spends the winter. Ortega says that her daughter is more active and independent than her two older children, who did not attend Head Start.

Involving parents who have worked in the fields all day can be difficult, but the Head Start staff has found that if programs are planned involving the children – like the Planada graduation – parents will come. They also like picnics and other programs involving food. Contreras, in her twentieth season with Head Start, said the most effective means of involving parents is “to make them welcome, to make them feel good about themselves. They always have something to teach me.”

Once the parents do come, they often help the centers by doing laundry or maintenance work. Each Head Start center has to raise part of its budget in these in-kind contributions. Westley must generate $38,175 and the Walter Thompson Center, $14,581.

On a typical day at the Westley center, the children do art work, listen to stories, go for rides on the four-seater “bye-bye buggy,” eat lunch, and take naps. You never know what has made an impression during any particular day or season.

Ismelda Cantu remembers. When she was in Head Start as a youngster in nearby Patterson, the center had some clothing someone had donated. “There was a red velvet dress that made me feel so good. I used to like to come in and put on that little dress. I loved it. But I didn’t know what I looked like in it because we didn’t have mirrors in the classrooms then. One day a teacher knew how I felt about that dress and walked me to the bathroom and held me up to see myself in the mirror in that little red dress.

“You remember when somebody made you feel special.”

©1996 Kay Mills

Kay Mills is a California freelance writer who is examining the Head Start program in America.