(SAN FRANCISCO) – Mark Dubois, chief friend and defender of the Stanislaus River, was wheeling the raft again. The racing water, the trees, the canyon walls, and the flecked sky whirred around in a languid blur. The universe was spinning and at the center was Mark, huge, bony, mostly naked, and grinning, each great paw gripping the handle of an out-sized oar, the arms penduluming mightily in opposite directions, making pirouettes in a sixteen-foot rubber Avon raft.

A roar announced another rapid. With the river swollen by snowmelt to 5,000 cubic feet per second, it would be big. We whirled around a bend. The river leaped and danced ahead. At the last second Mark straightened the raft and we plunged down a long series of four-foot rip waves. Sheets of icy water burst over the bow, tearing out my breath. I could sense a huge hole churning near the end of the rapid: water by the ton falling over a submerged boulder and crashing in upon itself with a frightful succckk! Mark went dead at it. Half the river seemed to be pillowing over the boulder. We curled over the glassy cushion and there was the bomb-crater hole, waiting to engulf us. We dropped into its maw. The river closed in from all sides ‘ half-filling the raft in a second. The hole held us for an eternity and then spat us out.

We glided on down the river. The roar of the rapid quickly diminished. Looking back, it appeared like a flowing white staircase.

“Devil’s Staircase Rapid,” said Mark, grinning. “Kind of tough sometimes.”

End of the Whitewater Run

We floated wordlessly for a while. The sound of the rapid faded into the chirrups of swallows and the quiet rush of high water. The canyon walls loomed in silence around us. I asked Mark if he knew how many times he had run the river.

“Lots,” was his answer.

“More than fifty?”

“Yes.”

“More than a hundred?”

“Yes.”

“More than two hundred?”

“Hmmmm. Maybe.”

Two oar strokes propelled us near shore. We held on to a precariously rooted bay tree while the river tugged at us. Half hidden by the tree was a grotto, twelve feet high, carved by the river out of the canyon wall. The exposed rock was cream-colored and marbled in black. “Columbia spider web marble,” said Mark. ‘.’It’s all over the canyon. Those cliffs up there are the same stuff. You just polish them a little and they shine like a museum piece. Amazing. A lot of San Francisco was built from this rock.” He motioned to the base of the wall. “Those little hollows down there are bedrock mortars used by the Indians to grind acorns.”

We let go of the tree and were swept away by the current. The rapids were fewer as we neared the end of the whitewater run, and now a stream of minutiae began to come from Mark about the river, the canyon, the climate, the geology, the wildlife, the flora, Indians, Italian fig farmers, gold prospectors, and all manner of persons, creatures, and plants which now, or once, inhabited the river canyon. It kept pouring out of him, as if sharing his long and unparalleled intimacy with the river was the cathartic experience he needed to struggle free of the knowledge that the place where we were was likely to be at the bottom of a reservoir in a few weeks.

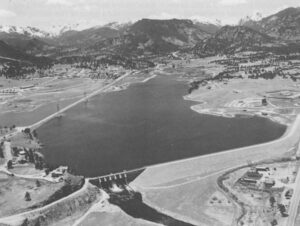

The Stanislaus River

For this was the Stanislaus River, rushing down from Sonora Pass in the Sierras, blocked thirteen times by dams on its way to San Francisco Bay, and now, after a ten-year battle, dammed again on its last long whitewater stretch. A few miles below us stood newly completed New Melones Dam, sixty stories high, a colossus of rock and mortar built to back a serpentine reservoir seventeen miles up the canyon, putting under several hundred feet of water the most popular whitewater run and one of the most beautiful river canyons in the West.

The dam’s builder, the Army Corps of Engineers, and its future owner, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, stood triumphant-brochures, dedication platform, and powerboat facilities at the ready-waiting to fill up the reservoir as much as the state of California would allow (which, for the time being, was only about halfway). The agricultural interests in the San Joaquin Valley were eagerly awaiting the water, which they could use to bring more and land into production or to help replace the groundwater which they have been over drafting at a rate of one-and-one-half million acre-feet, or some 480,000,000,000 gallons, per year. The people in the valley wanted the hydroelectric power so they could run their air conditioners against the hundred-degree heat.

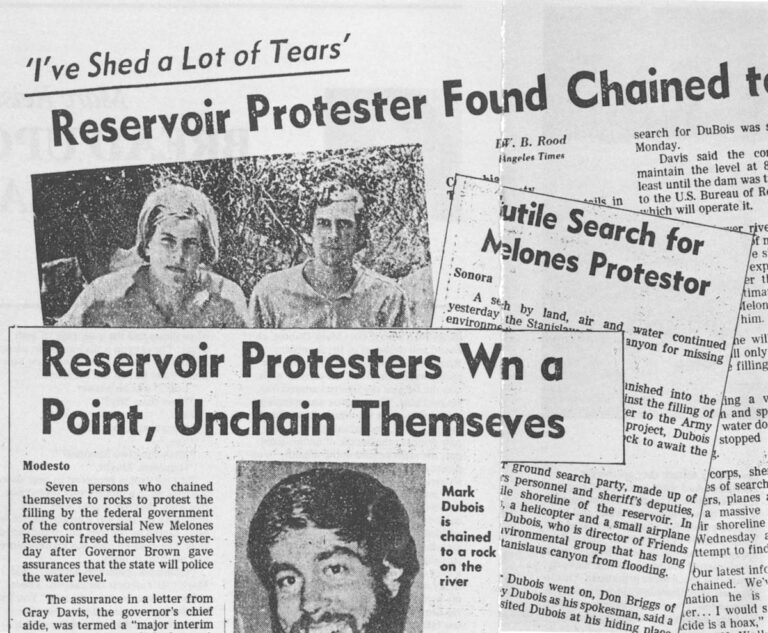

But they hadn’t reckoned on Mark Dubois. A few days after he took me down the river, he sent a letter to Colonel Donald M. O’Shei, District Engineer for the Army Corps in Sacramento. “Part of my spirit dies as the reservoir fills and floods the lower Stanislaus canyon,” he wrote. “The magic of this canyon should prohibit us from committing the unconscionable act of wiping this place off the face of the earth.”

Four days later, having spent a third of his life unsuccessfully trying to stop construction of New Melones Dam, Mark Dubois went into the Stanislaus River canyon, found a hiding place a few feet from the rising waters of the reservoir, had himself chained to a rock, and waited.

Transfusions of Water

The blood that flows through the veins of California is water. Without enormous transfusions of it, the greatest population center and the largest industry in the nation’s wealthiest state would barely be alive. Through an historical accident-or, if one prefers, through an act of hubris which surpasses even the location of great cities in an active earthquake belt-half of California’s twenty-two million people moved into an area with about 5 percent of the state’s water. So the water had to be brought to the people: sucked out of the ground, siphoned from the rivers, stored in reservoirs, and pumped through tunnels and over mountains to where it is needed. At the same time, California’s largest industry, agriculture- which contributes over ten billion dollars to the state’s economy and provides nearly 40 percent of America’s fruits and vegetables- gets, on the average, less than a quarter of the water it needs from rainfall. So the water has been brought to the crops, through the creation of the most extensive, expensive, and complex agricultural waterworks in the world, one whose Promethean scale overwhelms the mind.

These are the organs, veins, and arteries of California’s economy and civilization: the 1200 dams, the thousands of miles of canals, the millions of miles of irrigation ditches and troughs, the aqueducts reaching like long straws into the watersheds of the Sierra Nevada and the Coast Range and the Colorado River. Every river in the state, with three significant exceptions, has been connected to a gigantic plumbing system that brings water to cities and farms from as far as six hundred miles away. The flow of most of the state’s water has been literally wrenched around: a raindrop that falls near the Oregon border and would normally go out to sea there ends up being pumped into an irrigation furrow at Los Banos, five hundred miles south; a creek tumbling down the Sierra’s east slope toward Nevada is diverted into the faucets of Los Angeles.

Battleground of Values

Yet the influx of people into California has been so great, the consumption of water so prodigious, and its waste and misuse so appalling, that the state’s water system has always seemed inadequate soon after being expanded. It has not been significantly enlarged in nearly a decade, and southern California is about to lose half of the water it draws from the Colorado River to Arizona, so, from the water developers’ point of view, the system urgently needs to be expanded again.

One hears talk of vastly enlarging some of the existing reservoirs, of building giant new dams on the last wild rivers in the state, of bringing water down from the Columbia River, and even-though few take the idea seriously anymore-of capturing the immense Canadian rivers that waste” into the Pacific Ocean. At the same time, one hears muted whispers about vastly increasing the price of water to encourage efficient use, about intentionally creating water shortages as a means of inhibiting growth (something which the community of Santa Barbara has recently elected to do), about taking marginal lands out of production and no longer growing rice in an a Mediterranean climate, and even about tearing down dams and allowing rivers to run free again.

What is occurring in California-and, for that matter, throughout much of the West-is a protracted clashing of interests on a battleground of values, and it will dominate western politics at least for the remainder of the century.

William Mulholland

When William Mulholland stepped off the boat from Ireland at San Pedro in 1877 and rode the twenty-two miles to Los Angeles, he saw a ramshackle of 15,000 people sucking its precarious life out of the Los Angeles River. It was a drought year, and the sense of despair was palpable. The grass was withered and brown, cattle and sheep were emaciated and dying, and people were talking about abandoning the city. “Whoever brings the water,” thought the bluff and pragmatic Mulholland, “Will bring the people.”

It was Mulholland, after he had become the city’s chief water engineer, who brought the water. He went 240 miles across the Mojave Desert to get it, into the Owens Valley of the southern Sierra Nevada, and he and the city boosters who helped him (some of whom, notably the Chandlers and Otises of the Los Angeles Times became enormously wealthy for their efforts) took it by ruse, intimidation, and connivance. After they began to drain the Owens River into the Los Angeles Aqueduct in 1913, destituting a thriving agricultural valley in the process, they had to post patrols along the conduit to prevent the enraged Owens Valley farmers from blowing it up, but they had their water. And then the people came. During the next twenty years the population of the Los Angeles area increased more than sevenfold, and, by the 1930’s, the city had run out of water again. So the largest municipal water agency in the world, the Metropolitan Water District, was formed to bring water from the Colorado River-not just to Los Angeles but to all of southern California. With the cooperation of the Bureau of Reclamation, which built the largest concrete arch dam in the world at Boulder Canyon, a giant reservoir, Lake Mead, was created to store two years’ flow of the river, the Colorado River Aqueduct was constructed, and the crisis was relieved.

But the population of southern California kept doubling every twenty years, and by the late 1950s another water shortage loomed ahead. So, in 1959, southern California provided the votes for and northern California provided the opposition to, the State Water Project. It was another exercise in California superlatives: longest aqueduct in the world, highest dam in the nation, a ditch wider than the Panama Canal which could carry the flow of the Susquehanna River, and, to finance it all, the largest state bond issue in U.S. history. When Governor Edmund (Pat) Brown set off the first dynamite blast for Oroville Dam, the centerpiece of the project, a dam only 34 feet shorter than the Pan Am building in New York City, he said, “We are going to build a river 500 miles long. We are going to build it to correct an accident of people and geography.” In 1971, the California Aqueduct was completed, and the “accident” was partially corrected: nearly one trillion additional gallons of water began flowing from the northern part of the state to the parched southland.

But it still wasn’t enough.

Farms in The Desert

Most people in the East, and quite a few in the West, think of the western water crisis as being a problem of bringing water to cities built in the desert, but most of the water projects in the West have actually been built to bring water to farms located in the desert. The Central Valley of California, the richest agricultural region in North America, is just that: a desert. Not a Sahara or a Gobi Desert, for there is some rainfall; about twenty inches per year in the northern end and six inches per year in the south. But this is too little for most varieties of crops which need at least three feet, and almost all of the rain in the valley comes between December and March, when there is too much frost danger to grow much of anything at all.

So the only way to farm the Central Valley has been through irrigation. Today, irrigated agriculture consumes 85 percent of all the water used in California; everything else-homes, lawns, factories, schools, offices, car washes, fountains -divides the rest.

Except for the development of an extraordinarily mobile society, which would be paralyzed without automobiles, the growth of irrigated agriculture forms the most significant chanter in the history of California. Only a century ago, the Central Valley was almost entirely dry farmed and planted in wheat -a sea of grain across which clanking mechanical harvesters glided like ships. But the land did not suffer dry farming well, and with the influx of population (and, later, the advent of refrigeration) farmers began to realize that they could grow much more valuable cash crops if they irrigated their land instead. They could do this in two ways: by pumping groundwater, or by forming irrigation districts to build dam, diversion, and reservoir projects. Often they did both, but groundwater was by far the most important source of supply (on the drier west side of the valley, it was for a long time the only source).

The Central Valley Project

By the 1920’s, irrigation had taken hold so tenaciously that California was one of the three most successful farming states in the nation, and the groundwater resource upon which its success depended was seriously depleted. There was no regulation whatsoever over groundwater pumping (there still isn’t today), and everyone expected everyone else to keep pumping even if they themselves held back, so it became obvious that the only way to save the state’s agricultural industry over the long term was to build a huge project to provide supplemental surface irrigation water for the Central Valley. The project was planned and mapped in detail in 1933, christened The Central Valley Project, approved by the voters-and then it died. The bond market during the Depression was as arid as the West, and the only security for payment of interest and principal on the immense project would be revenues from water and power sales arriving many years later.

The Bureau of Reclamation inherited this first great water project-not a mere dam, not a canal, but several huge dams and hundreds of miles of canals. It was a plan to play God with the waters of California, a plan which the Bureau itself hadn’t had the imagination to conceive. Fortunately for the Bureau and for California, its new commissioner under FDR, an aggressive, independently wealthy former public relations man named Michael Strauss, had the combination of vision and boldness and ego that his predecessors had lacked. Strauss was a mover, a doer; like his successor in spirit, Governor Edmund (Pat) Brown, he loved building things: and even if the Central Valley Project was a rescue project for California farmers, many of whom held thousands of acres and had no business receiving subsidized federal water at all, he was going to build it.

And he did, and so changed the West.

To The Rescue

From that point on, western landowners began to expect the Bureau to rescue them if they over-drafted groundwater, and the political importance of the Bureau quickly became obvious to western members of Congress. Before long the Bureau was practically run by a succession of powerful western Senators and Congressmen- Carl Hayden, Clinton Anderson, John McFall, Bizz Johnson, Wayne Aspinall, and others who encouraged it to build more and more projects (including ludicrously extravagant ones designed to benefit a few of their most cherished constituents) and who protected it, nurtured it, and fed it with the nation’s wealth, until the Bureau had grown into a huge, blind, bullying bureaucracy which was beyond the control of the Interior Department, the President, and, quite literally, the law.

Years later, when the Central Valley Project would amass a $10.4 billion cumulative deficit as a result of selling water in the desert for a penny a ton (the cheaper the water, the greater the demand, and the more projects the Bureau could build), people would ask how such a thing could have been allowed to happen.

With continuous additions to the original Central Valley Project, and the first deliveries of State Project water in the early 1970s, an additional two-and-one-half trillion gallons of surface water became available to the state. Most of it was immediately drained off by irrigators in the San Joaquin Valley, the arid southern half of the Central Valley. By the late 1970s, the total area of irrigated land in the state exceeded nine million acres, and California sat on its throne at the top of all the agricultural producing states in the nation. In 1978, agriculture pumped $10.4 billion into the state’s economy, an amount which exceeds the gross national product of many smaller nations. The future of agricultural industry, and of the state, looked comfortably secure.

But it isn’t. For California is beginning to discover (as it might have done long ago had it looked carefully into history) that the problems of irrigated agriculture are never really solved; they are merely alleviated. And when an irrigated empire such as California receives enormous quantities of heavily subsidized water and bases its future upon the assumption that an infinite quantity of cheap fossil fuels will always be available, it develops a complex set of internal irrationalities that make its future that much more precarious. This is irrigated agriculture in California today: a phenomenally successful, deeply subsidized industry, caught up in consumptive paralysis, and facing a strange set of problems which may prove to be its undoing -inflation, the exhaustion of oil, environmentalism, and salt.

Ed. Note: On May 24th, the Army Corps of Engineers decided to stop filling the New Melones Dam for the duration of the spring at the level requested by Mark Dubois.

©1979 Marc Reisner

Marc Reisner expects to write more about California’s water problems in our next issue.