Brooklyn, NY — It was one of those New York City summer days when the heat bounced back and forth between buildings and the asphalt seemed to sweat. The temperature alone was cause for irritation.

The police department’s timing could not have been worse. Convinced that a murder suspect was hiding in an East Flatbush neighborhood, several patrolmen blocked off the busy intersection of Nostrand Avenue and Beverly Road and randomly stopped and checked cars.

On any other day, residents of this bustling Haitian immigrant enclave might have considered the searches just another inconvenience of urban life. But this was no ordinary day. It was June 8, 1999 and the mixed and controversial verdicts had just been announced in a federal court case involving several police officers accused of brutally beating and torturing a Haitian immigrant. One officer was convicted and three were acquitted.

Many people out on the street that day saw a different motive in what the New York City Police Department says was a routine operation.

“They did this to harass us,” one highly offended resident commented. “They’re getting even with the Haitian people.”

“They are afraid we’re going to riot,” someone else sneered.

Officer Ivan Pierrelouis was inundated with questions that day as he canvassed the neighborhood. People demanded to know why the NYPD would choose that day, of all days, to show up in such force.

“I had to go around and explain that the checkpoint had nothing to do with the verdicts,” he said, “and that we were not harassing them or provoking them and that this is something we do everyday. But the Haitian people were convinced it was because of the verdicts.”

For days afterward, Pierrelouis, a Haitian native himself and, at the time, the police department’s liaison to the city’s Caribbean immigrant community, was flooded with telephone calls about the barricades.

“Eventually, they started to believe me,” he said. “But it wasn’t easy.”

Things had not been easy since the night in August 1997 when an Haitian immigrant named Abner Louima was arrested outside a neighborhood nightclub, beaten by New York City police officers and sodomized with a broomstick inside the stationhouse bathroom.

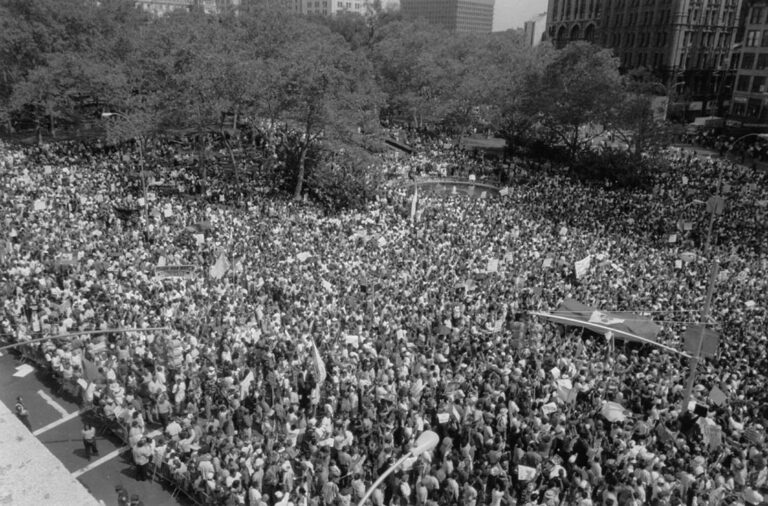

The incident became a symbolic point of contention in New York’s community of Haitian exiles and an important test of the political potency of the 250,000 Haitian-Americans living in the city, the majority in Brooklyn. Galvanized, they quickly organized protests, enlisted the help of leaders from other ethnic groups, and formed coalitions with diverse religious and civil rights organizations.

Abner Louima’s beating completely undermined the NYPD’s earlier efforts to win over a people with a deep distrust of law enforcement and entrenched memories of police brutality in their native country where corrupt officers worked alongside the crooked military to prop up a 29-year dictatorship. Distinct uneasiness about the police was replaced by outright disgust.

Thousands of Haitian-Americans, some holding plungers aloft to symbolize what was originally believed to be the instrument used to sodomize Louima, descended on City Hall and in front of the 70th precinct in Flatbush, where the assault took place.

The NYPD hurriedly responded. Meetings were arranged between the police commissioner and Haitian community leaders. Precincts were reshuffled and ranking police supervisors reassigned. Haitian community members were invited to observe police training programs and to conduct tutorials on Haitian culture for officers. There was a sense in the Haitian community that their anger was being channeled into something bigger, that they were gaining political power. This time their complaints were not dismissed as minority group whining but embraced by people of various races and political affiliations whose collective revulsion over the Louima beating lent support to their calls for accountability by the NYPD.

“They were able to mobilize around this case unlike any other group has been able to do,” said Gary Pierre-Pierre, editor of The Haitian Times, a national English language newspaper based in Brooklyn. “There have been equally disturbing events in the Latin community but they were unable to muster the kind of public display of anger that the Haitians were able to do.”

Still, five years later, Haitian-Americans are still measuring the long-term effects of their struggle with the NYPD and are still debating among themselves how much political clout they gained as a result. Last November, five Haitian-Americans ran for New York City Council seats and two ran for the New Jersey State Assembly and none were elected. It was a disappointing outcome for the half million Haitian-Americans in the New York and New Jersey region. They make up the largest population of Haitians in the United States but have yet to define themselves as a potent voting block, as their compatriots in South Florida have successfully done.

This illustrates the challenges the community faces in turning major political issues in their communities into lasting political benefits.

“While those who rallied around the issue of police brutality were successful in raising the issues, they were lacking in the political skills needed to work behind the scenes to achieve the real, tangible results that would eventually empower the community,” Pierre-Pierre said.

Still, the activists kept the pressure on at a crucial time as the NYPD struggled to reshape its image in the eyes of Haitians and other increasingly politically astute immigrant groups. In a department that had already been roiled by accusations of police brutality by other ethnic groups — notably African-Americans and Latinos — the negative media coverage of the Louima beating was a public relations disaster. And it happened during the time the city was trumpeting its falling crime rates and improved quality of life.

Mayor Rudolph Giuliani was being castigated in newspaper editorials as a bully with a police force run amok. The damage had to be repaired or Haitians here would forever link the NYPD to the same violence they fled back home, making good working relations all but impossible.

“When a Haitian sees a police officer, instead of thinking this is someone there to protect them or serve them, they think this is someone to be careful around, to stay away from as much as possible,” said Manfred Antoine, president of the Alliance of Haitian Émigrés.

For Haitians, especially those who can’t speak English or are living in this country illegally, that fear is amplified because they feel more susceptible to abuse.

And they aren’t alone. The city is home to people of 178 nationalities who speak 200 languages and live in widely distinct neighborhoods. The NYPD clearly had its work cut out.

“We felt very strongly that if we were going to forge relationships with these diverse communities, there had to be a real, working understanding of these communities, their language and their culture,” said Yolanda Jimenez, the department’s former Deputy Commissioner of Community Affairs. Last January she was appointed Commissioner of the Mayor’s Office to Combat Domestic Violence.

To help better understand those communities, the NYPD developed the “Streetwise” program to teach recent graduates of the police academy basic knowledge of language and culture as a policing tool in immigrant communities. Designed in conjunction with City University of New York, the program has been tailored for Chinese, Haitian, Hispanic and Russian and South Asian communities.

So far 5,000 new officers of the academy have received the training and the department is now planning to train veterans with five to 10 years of experience.

“This is a skill we know officers will need and utilize,” said Ms. Jimenez, a Colombian immigrant who came to New York at age three.

That’s where Pierrelouis, the department’s self-proclaimed “diplomatic liaison” came in. The NYPD has 12 such liaisons for various immigrant groups in the city.

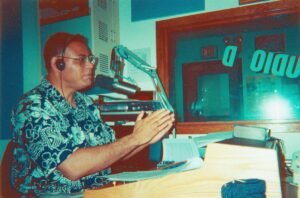

Pierrelouis, 40, a father of three, immigrated to the United States as a teenager in 1974. He is now a detective working in the police department’s intelligence division. When he was a liaison officer, he worked the streets of East Flatbush visiting Haitian record shops, Jamaican restaurants and Trinidadian grocery stores to pass out informational police department flyers written in English and Haitian Creole. He spoke at neighborhood association meetings and urged residents to join their local police precinct community councils. He took questions on Haitian radio call-in programs. At his desk at NYPD headquarters, he fielded calls from community members and Creole language media.

In some neighborhoods, he was such a familiar presence that residents often called out, “Hey Pierrelouis, sak passe?” (“What’s up?”)

The NYPD also made sure non-Haitian officers were more visible in Haitian neighborhoods.

Raymond Joseph, editor and co-publisher of the Haiti Observateur newspaper, said people in the community noticed.

“We see policemen at special church programs. We see them coming to the community centers. We see them at block parties playing with the kids. They are definitely trying to present a different image,” said Joseph, who was on the Mayoral Police/Community Relations Task Force, created two weeks after the Louima beating.

Jocelyne Mayas, a veteran Haitian activist who started the Queens Empowerment Center for Haitian Immigrants, was not as easily convinced the department was trying to do better. She stayed angry at the police department until she and other Haitian activists took part in a 14-week course at the NYPD’s so-called Citizens Police Academy designed to give civilians a better understanding of police work.

“It is not the whole institution, or all the police department, it is certain individuals,” said Ms. Mayas, who now works at the New York State Citizenship Unit, the agency charged with helping new immigrants to the city. “Were it not for these classes, I would still hate them.”

It also helped that she met some of the city’s Haitian-American police officers. “They are a real bunch of gentlemen,” she said.

Ms. Mayas’ comments illustrate that though Haitians may look askance at the 40,000 police force in general, that feeling doesn’t always extend to the Haitian-American officers on the force. In fact, the officers were a source of pride in the community when 25 of them, including Pierrelouis, volunteered to go to Haiti in 1996 as part of a U.S. State Department program that used a team of international police officers to train the fledging democracy’s new police recruits.

The irony of the training mission was not lost on Pierrelouis, a proud, 12-year veteran of the department: here he was teaching his countrymen to respect civil and human rights while back in New York cops were violating Haitian civilians.

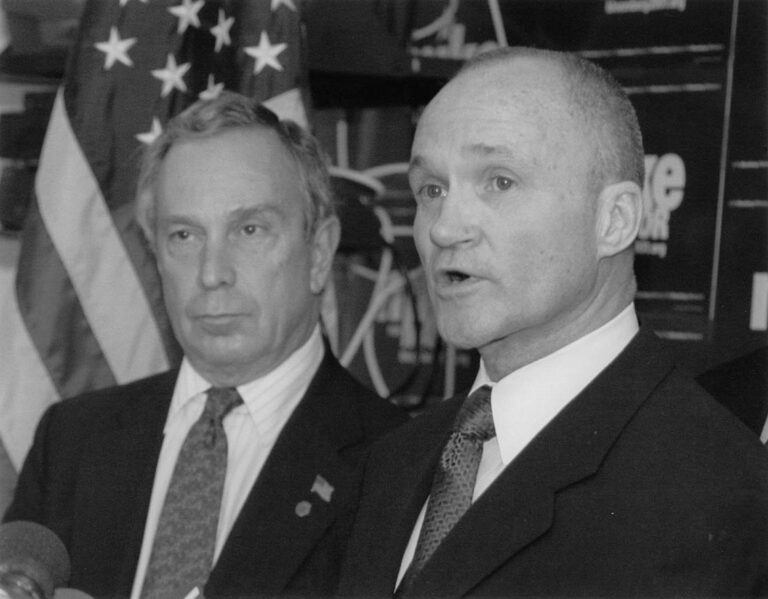

This January, the city’s new mayor, Michael Bloomberg, hired former NYPD commissioner Raymond Kelly for his old job. After leaving the commissioner post in 1994, Kelly oversaw the police training program in Haiti.

After the last of the officers had returned from Haiti in June 1998, they formed the Haitian American Law Enforcement Fraternal Organization, or HALEFO, to foster understanding between the police department and Haitian immigrants. “We are not a political organization,” said Sgt. Guy Cethoute, a HALEFO member who also spent time in Haiti, “but with Abner Louima came all these other issues that needed to be addressed in law enforcement within the Haitian community.”

The Louima beating took place on the weekend Det. Pierrelouis returned from his nine-month tour of duty in Haiti. He learned about it while riding the Long Island Railroad headed to his first day back at work. “Oh no,” he mumbled to himself as he read the news spread across the front page of a New York tabloid. “This is huge.”

By the time the train pulled into Penn Station at 6:30 a.m., his stomach was in knots. He called his supervisor at home.

“’Captain, we have a problem,’” he recalled telling his boss. “’We have to do something.’”

Pierrelouis arrived at One Police Plaza and immediately began working the phones. He called Haitian community leaders and clergy throughout Brooklyn and invited them to meet with the mayor and police commissioner.

By 5 p.m. that day, 50 people were meeting with Mayor Gulianni and Howard Safir, who was the police commissioner at the time.

“The mayor and commissioner spoke honestly and explicitly to the group,” Pierrelouis recalled.

Every morning thereafter, Pierrelouis wrote summary reports of the ongoing investigation and faxed them to local Haitian radio stations for their broadcasts.

“I wanted to make sure the Haitian community understood what was going on,” he said.

The quick damage control was crucial in keeping the lines of communication open. Several more meetings between Haitian groups and the department followed. One meeting drew some 500 people.

“The police department is asking us to work with them but they have to give us something back,” Serge Demorcy, a Haitian community activist from Crown Heights, said at one such meeting.

Police officials say they have given back. Some recommendations made by Haitian political leaders were adopted. Haitian clergy and organization heads now conduct sensitivity training seminars for officers. Each precinct now has a lieutenant on desk duty instead of a sergeant.

Pierre-Pierre, who covered the Louima story when he was a New York Times reporter, said the changes were minor and largely symbolic.

“Those efforts benefited the image of the police department but didn’t necessarily help the Haitian community,” he said. “It was good for the entire city, but the Haitian community’s gain was limited.”

Two proposals made by Haitian leaders that would have had more impact were never implemented. They wanted the NYPD to institute a residency requirement for new cops and for the state legislature to repeal the so-called “48 Hour Rule” which allows officers accused of a crime to refuse questioning by authorities for two days.

What’s more, the Louima incident was followed three years later by another controversial confrontation between a Haitian immigrant and New York City police. Patrick Dorismond, an unarmed security guard, was shot dead after being mistaken for a drug dealer by undercover police. In that case, Commissioner Safir and Mayor Gulianni vigorously defended the officers involved and initially refused to apologize to the dead man’s family.

Tensions have since cooled between the two sides and their relationship, like the Haitian community’s political standing, is still evolving.

“I would say the relationship is fair,” said Pierrelouis. “I think it will improve under Raymond Kelly. The Haitian people love him. They think he’s the kind of guy they can trust and that he did a good job in Haiti and laid the foundations there for a better, less abusive police force.”

©2002 Marjorie Valbrun

Marjorie Valbrun, a reporter for the Wall Street Journal, is researching Haitian immigrants’ emerging American identity.