The ecological concern Pope Francis has sparked among Catholics –and resistance to it– reflect how the faithful are split over the climate emergency, the role of capitalism, and where 1.3 billion global Catholics should put their money and clout.

Powerful detractors say Pope Francis’s attention to climate change comes close to paganism, an attempt to turn environmentalism into a religion. Supporters steer money away from fossil fuels, taking a moral stand against destruction of the earth.

Francis’s planned attendance at the November U.N. climate change conference in Glasgow, COP26, is only the most recent example of his environmental focus. The first encyclical written entirely by the pope, Laudato Si’, On Care for Our Common Home (2015), addressed “to every living person on this planet, linked human beings with all of creation, describing a God-given interconnectedness that obligates people to make decisions in light of protecting the earth, while preserving human dignity. He criticized the belief that science and technology alone will save the world from destruction. And he called “all people” to an “ecological conversion” that recognizes connections to each other, to other forms of life and to the sacred. Unfettered capitalism and consumerism, he said, harm the planet in ways that may be irreversible.

Francis wrote the encyclical with an interfaith panel of global experts in science and economic development just in time for international meetings on sustainable development goals, and the summit (COP21) that produced the Paris Accords, which legally binds nations to limit greenhouse gasses. In the words of scholar Irene Burke, a fellow of the Liechtenstein Institute on Self-Determination at Princeton University, the encyclical and experts’ work contributed to “political cooperation leading up to pivotal international agreements.” Ahead of Glasgow, scientists and leaders of the world’s religions will meet in a Vatican conclave, “Faith and Science: towards COP26,” to draft a document directed to global leaders.

Detractors of the pope– some avoid his title by referring to him as “Bergolio,” his surname, or “the Argentine,” referring to his homeland — consider his environmental stand as another example of what they regard as the prelate’s infelicitous governance of the 2000-year old institution. In their eyes, he violates Church norms with his openness to people of different faiths, homosexuals, and divorced Catholics. An adherent to the spirit of Vatican II (1962-1965), the landmark conference to bring the Church into the modern world, the pope is not traditional enough for Catholic conservatives, and his stand on ecology is a target.

Cardinal Raymond Burke, who has led the dioceses of St. Louis and La Crosse, and serves as patron of the Sovereign Military Order of Malta in Rome, is a leading voice among traditionalists. “With regard to ‘ecological conversion,’ what I see behind this is a push for worship of ‘Mother Earth,’” he said in an interview with The Wanderer. Burke called ecological conversion “insidious,” tantamount to “idolatry.”

In an address expressing solidarity at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic, Pope Francis said that before the virus hit, people had “carried on thinking we would stay healthy” in a world that was “sick” from wars, injustice, and failure to “listen to the cry of the poor or of our ailing planet.” Former papal envoy to the United States Archbishop Carlo Maria Vigano said that Francis should have laid the blame for COVID instead on “the righteous wrath of God offended by the countless sins of humanity.”

“I would like to emphasize that attributing a personal identity to nature, almost endowed with intellect and will, is a prelude to her divinization,” warned Vigano in an address to an October, 2020 conference.

In 2019, Catholic conservatives, and the rightist Catholic media that echo them, attempted to undermine the public perception of the pope’s goals. They managed to grab the spotlight during the time of the Pan-Amazon Synod in Rome, called to put Catholic environmental thinking into concrete terms in a region that spreads across nine countries. Conservatives mocked the appearance of invited native leaders who wore traditional feathers and body paint, incorrectly branding their ancestral beliefs as “pantheism.” (Francis considers the Indigenous to be protagonists of conservation of the places they live and respects their spirituality.)

![Luis Torres, a member of the Ticuna Indigenous tribe, administers the social pastoral outreach office at Our Lady of Peace Cathedral in Leticia, Colombia. As the 2019 Amazon Synod took place in Rome, 6,000 miles away, he said, "The Church will never leave its structures. But the Amazon is my Mother Earth. The Church here must have an Indigenous face. It must dialogue more [with the Indigenous], must listen harder." Photo by APF fellow Mary Jo McConahay.](https://aliciapatterson.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Pope_McConahay05.jpeg)

During the Synod, conservative Catholic media, multiplied by Twitter and YouTube, focused on an Austrian named Alexander Tschugguel, making him a hero of radical traditional Catholics (“rad-trads”) for sneaking into a Roman chapel at night, stealing hand-carved figures that had been a gift to the pope, including one of an unclothed pregnant native Amazon woman. He spirited them to a bridge on the Tiber and – as a companion filmed – hurled them into the water. The media called it “the splash heard round the world.” Ironically, Tschugguel was an anti-abortion activist, and the female figurine was a symbol of fertility to fast-disappearing Amazon natives. Retrieved by carabinieri, the statue was honored with a place in the Synod hall while bishops deliberated, but damage had been done. The oxygen around the event was sucked into the colorful episode, diminishing public attention to key preoccupations of the pope: the sacredness of the natural world; the lives of the poor, in this case Amazon natives and migrants looking for work, and the struggle between preserving natural resources and human greed.

On the side of the Catholic divide which honors the reforms of Vatican II, environmental activism rejects the “magical conception of the market,” as Francis calls it, to solve issues of poverty and environmental destruction. Instead, following Laudato Si’, the Catholic environmentalists advocate decreasing the pace of production and consumption, which amounts to a challenge to laissez faire capitalism. This puts the Church in a delicate position with some of its most conservative – and generous – members, who support think tanks and youth groups.

Prosperous Catholics including pro-life Domino’s Pizza magnate Thomas Monaghan or anti-gay activist and resort mogul Timothy Busch, donate to anti-abortion efforts and ballot measures such as those against same-sex marriage. Busch’s annual week-long Napa Institute hosts a Who’s Who of prominent Catholic speakers and wealthy conservatives, who share worship, contacts and wine tastings. Money also comes to Catholic conservative causes from non-Catholics aware of the sway of the Church in secular affairs. Oil billionaire Charles Koch, together with Busch and other wealthy individuals, cobbled together a $47 million donation for a business school at the Catholic University of America in Washington D.C. Busch told the Washington Business Journal he was proud to support the school’s “vision for an educational program that shows how capitalism and Catholicism can work hand in hand.”

By connecting environmental awareness to demands for attention to the impoverished, who are affected first and most grievously by climate change, Francis extends Catholic environmental ethics to include the “preferential option for the poor,” a driving force of the revolutionary Liberation Theology born more than fifty years ago in his Latin American homeland. A social and political movement that spread after Vatican II, Liberation Theology interprets the Gospel through the lived experiences of the oppressed. It describes “structural sin” built into many societies that limits opportunities for marginalized people. As an Argentine cleric, Jorge Mario Bergolio practiced a version called teologia del pueblo(theology of the people). The earth, he says in Laudato Si’, is “the most abandoned and maltreated of our poor.”

Bergolio studied science as a young man, and worked as a chemist at a food science laboratory in Buenos Aires before he became a priest. He clearly links climate change to human action, and respect for science is prominent in his thinking. In 2014, in his first address to the Pontifical Academy of Science, as Pope Francis, he said, “The approach of the Christian scientist is that of investigating the future of humanity and the earth, and, as a free and responsible being, to contribute to preparing it, to preserve it, and to eliminate any risks to the environment, both natural and manmade.”

In 2019, before a meeting of lawyers and jurists in the Vatican, Francis introduced the concept of “ecological sin,” adding that he might include it in the Catholic catechism. Certain Catholic media had a field day attacking the concept, which the pope defined as an act or omission “against future generations…manifested in the acts and habits of pollution and destruction of the harmony of the environment.” The conservative Life-Site News quoted “top Catholic thinkers” who blasted the pope’s theology, averring that people cannot sin against the earth, only against God or other people.

The U.S. Catholic Conference of Bishops (USCCB) expressed concern for the environment in the early 1980s. But more recently, since ecological destruction has become known as an issue reflecting the worldview of Pope Francis, linked with his critique of neoliberalism and free-market capitalism, the conservative conference has neglected environmental advocacy and put its energy primarily into campaigns over abortion and denying Holy Communion to politicians, including President Joe Biden. Researchers at Creighton University have found that most Catholics learned about the pope’s environmental thinking in public media, not Church media, and that around the time of Laudato Si’’s publication only one percent of diocesan media, all under the purview of bishops, mentioned climate change or global warming. With some exceptions, bishops remain little involved in promoting “ecological conversion,” or criticizing unbridled capitalism as a factor in the climate crisis.

But care for “our common home,” as Francis calls it, has caught fire among many ordinary Catholics.

“I realized how much faith is part of environmental awareness, of creation,” 22-year-old Kyle Rosenthal of Rochester, New York, told me by telephone. A recent graduate of Boston College, Rosenthal is coordinator of the Catholic Divestment Network, an environmental activist network of 27 Jesuit colleges. He lobbies his university administration to take its investments out of the fossil fuel industry, so far unsuccessfully, despite Pope Francis’s call for Catholic institutions to do so. As a personal project, Rosenthal is urging change in the USCCB investment guidelines, which haven’t been updated since 2003.

“It’s not just the youth, but the bulk of people are frustrated that the environment is not prioritized,” said Rosenthal. “The bishops’ ‘pre-eminent’ issue is abortion, while environmental destruction is actively killing people daily. They can hold multiple issues in mind.”

The U.S. Catholic Climate Covenant, begun in 2006, provides videos, webinars, “homily helps” and other resources for mobilizations with partner colleges, universities and religious orders. The Laudato Si’ Movement (formerly the Global Catholic Climate Movement), which advocates lobbying, public organizing, and lifestyle changes to support the pope’s call, claims one million members in 90 countries. The number of its Laudato Si’ Circles, small groups where members “make the words [of the encyclical] come to life,” as one participant put it, grew 279 per cent between 2019 to late 2020, from 47 to 178 circles on six continents.

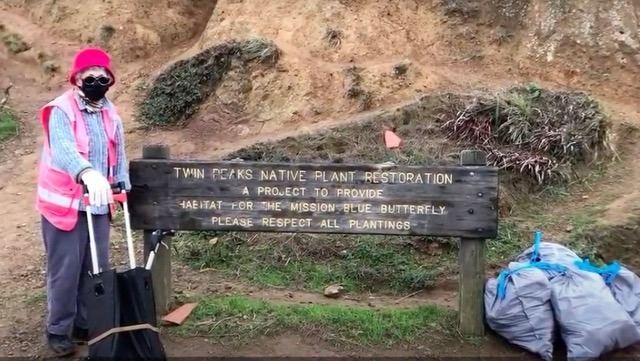

Mary Klipp, a retired medical social worker, joined her parish’s Laudato Si’ Circle when it began in 2019, she said in an interview at her apartment overlooking San Francisco Bay. Circle members pray, reflect, share information, change their consumer habits, plant food gardens, organize beach and river clean-ups, and lobby government representatives on issues like destructive mining. Klipp regularly climbs a hill near home to a 64-acre park with a gorgeous view to collect trash like coffee cups and candy wrappers people have left behind, giving wildflowers room to breathe, likening the activity to prayer. Her son, Josh Klipp, an accessibility consultant, filmed his mother’s rounds one day so she could present a video by Zoom at her parish’s hospitality hour during a pandemic lockdown. She walks among trees, spears flotsam from bushes and from the ground where it has been tossed, puts it in a bag to take away. As she works in the open air, we hear her say, “One can sense the Earth, the Earth Spirit, the Sky Spirit, the Creation Spirit that was the joy of St. Francis,” the patron saint of animals and ecology. She tells the flowers, “May you never be taken for granted!”

Mary Rose LeBaron, 48, a sales professional, spent six weeks online with others from the Philippines, Sweden, Germany and India, learning to be a Laudato Si’ Circle animator for the group to which Klipp belongs. Since then, LeBaron has met monthly with about eighteen members, an encounter that “has been definitely an opportunity to deepen my faith life.”

“Essentially it’s an awakening,” said LeBaron. “We realize, ‘I’ve been enjoying the status quo. Is this sustainable? Am I caring for my fellow human beings?’” A by-product of meetings is “learning the importance of community,” she said, “what was concerning them the most, what mattered to them.” In individual encounters, people spoke to her of their grandchildren, she said, wondering whether there would be a future for them.

“I saw tears welling up in their eyes,” she said.

Mary Jo McConahay examined the role of women in the Catholic Church during her fellowship year. Her work contributed to her latest book, “Playing God, American Catholic Bishops and the Far Right.” (Penguin/Random House).