For years, murals in Los Angeles have been documented and celebrated, but an even more popular street art—hand-lettered signs—largely exist under the radar.

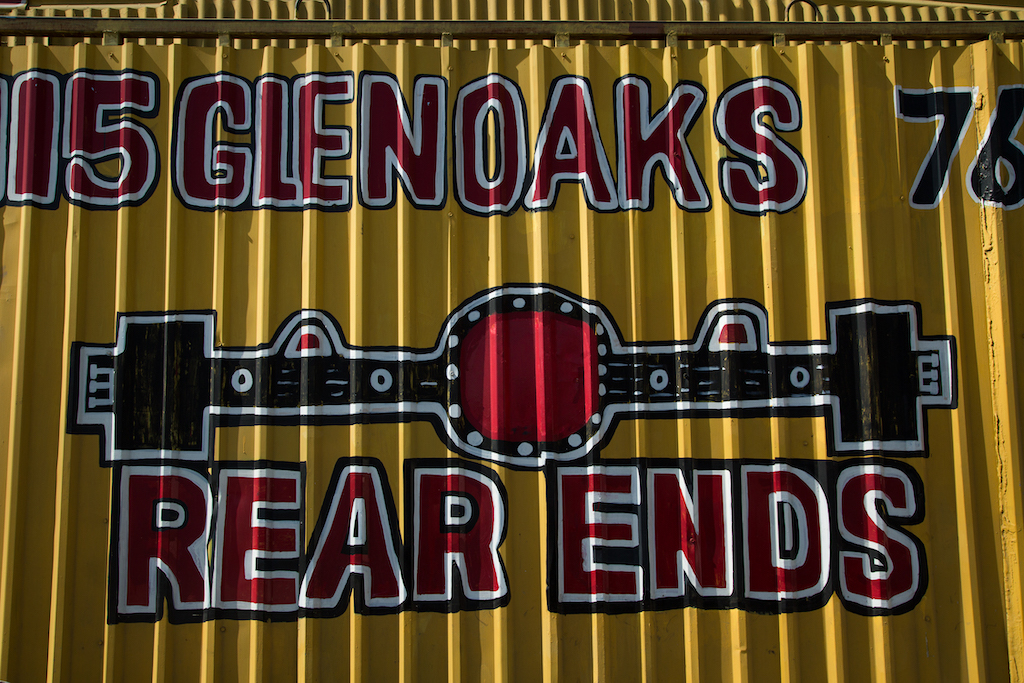

These advertisements have long flourished throughout this far-flung city and, happily, are enjoying a spirited renaissance. From car logos carefully painted on curvy, corrugated fences at body shops to playful food cartoons on restaurant façades to chatty slogans arrayed on the exterior walls of hardware stores, the city is awash in great hand-painted signs. Whether beautifully rendered by trained professionals or crudely drawn by amateurs, the signs are often witty and idiosyncratic—the antithesis of franchised sameness.

There are several reasons for the popularity of hand-lettered signs in Los Angeles. The city is home to the nation’s last remaining commercial sign-painting program at L.A. Trade Technical College. The Hollywood entertainment industry creates a steady demand for sign artists and scenic painters, and taggers, graffiti, and tattoo artists often pivot to sign painting or do it on the side. Los Angeles is also home to immigrant communities with itinerant sign painters who create signs anonymously for quick cash, and hipster shop owners, tired of the cold perfection of digital signs, who embrace the artistic flair of hand-painted advertisements for their storefronts.

The signs often reflect the flavor of a neighborhood. For example, several signs have nautical themes in Wilmington, near the Los Angeles harbor. In Latino neighborhoods, signs are commonly a mix of Spanish and English, sometimes with unexpected results. For example, at the Garcia Mini-Market in the historic South Central neighborhood, under the painted letters “PRODUCTOS CENTROAMERICANOS” are hand-drawn renderings of English language items: Bounty paper towels, Mazola oil, and a can of “oven grill cleaner.”

Freelance interpretations of brand-name products, from chewing gum to batteries, are seen on storefronts across the city, decorating the exteriors of food shops, dollar stores, and tire marts. Hipster neighborhoods favor less busy façades and spare lettering.

More commonly, painted signs reflect the personality of a store’s owner, sometimes literally. For example, in the Jefferson Park neighborhood, the Walter Goode Sports Academy was graced with an action shot of owner Walter Goode (“10th-degree black belt”) with his right leg kicking to the sky. At a mini market and party shop nearby, “Proverbs 16:3” was painted above the doorway, just under a depiction of a bottle of Clorox, a bunch of balloons, and the Muppet character Cookie Monster. Inside, owner Emilsa Del Cid, with her well-worn Bible, showed the passage she asked an itinerant painter to add to her store’s exterior. (“Commit your actions to the Lord, and your plans will succeed.”)

At their heart, hand-lettered signs are connected to people, and people are endlessly fascinating. Despite the velocity and scale of a flawed, overburdened metropolitan area of 13 million people, businesses and people have to differentiate themselves from everyone else. A business owner puts up a sign, a signal to say “I am here,” “This is me,” or “This is what I do.”

Signs are always in a language that the people around them understand, a language that includes not only words but symbols, color, texture, patina, and style. In time, these signs accumulate their histories and stories, and they become a mechanism by which to investigate and understand the city.

Doc Guthrie, who has been in the hand lettering business for half a century and led the sign graphics program at L.A. Trade Tech for 28 years, says most people entirely overlook the value of signage. He constantly challenged new students and lectured audiences by asking: “How did you get here today? What if there were no street signs, stop signs, or on-ramp signs? No hospital emergency room signs? No pizza signs and, more importantly, no liquor store signs? How would you get here?”

“They get it all of a sudden,” Guthrie adds. “We are indispensable. We are absolutely indispensable.”

However, professional sign painting schools are not an indispensable industry. These schools used to be found in all major cities and were as common as barbering colleges or cosmetology schools. But as vinyl stick-down and digital letters took over the market, even famous schools in Boston and Chicago closed their doors by the turn of the last century. There are now a few places offering workshops, but L.A. Trade Tech is the only school offering an extensive program of sign painting skills.

The sign graphics program is long and rigorous. It consists of four semesters (two years) of classes that meet from 7 a.m. until noon four days a week. Courses include the science of letter shapes, drawing and brushing, window signs, painting on glass, using 23-carat gold leaf, and advanced computer design.

Despite its long history since 1924 and numerous successful alumni, the Los Angeles program almost shuttered in the 1990s. Guthrie recalls recruiting students through the parole office and court system and enrolling graffiti offenders. He says one year, the program had only 14 new students registered, one short of the number needed to stay viable. So, he signed up a guy on the street to keep the doors open. Things started turning around in 2012, after a documentary, “Sign Painters,” was released. The documentary featured individual sign painters and included the L.A. Trade Tech program. As the film reached audiences, the program started getting students from across the globe.

Juan Carlos Aguilar has been teaching in the program for eight years and runs a sign painting company, El Sapo Studio, on the side. He graduated from the program in 1997. Although several students in class with him went straight into the tattoo industry, using the lettering skills they learned in the program, Aguilar has stayed with sign painting. He first worked at a few digital sign shops but didn’t like it. Digital inkjet printing is inexpensive, he notes, but printers lay down only a thin layer of ink. There’s a solid, thick layer of enamel paint with hand painting that lasts a long time. “I think businesses are starting to realize that digital prints don’t last,” he says.

He and Guthrie say they are encouraged by the recent interest in and appreciation of hand-crafted lettering. “Customers often can’t articulate it, but they innately know what looks cool and hand-painted and what looks digital,” Guthrie says. “I used to paint window signs, and if you get on the inside and the sun is passing, you see all the brushstrokes. And people used to want me to paint a white cover on it. Now, they say, ‘No, no, no, I want to see the strokes. It’s authentic.’ Oh, they love it when they see brushstrokes now.”

Noé Montes is based in Southern California and creates documentary work around a social issue or geographic location. He uses the work as a tool for community engagement through exhibits, workshops, and community dialogues. During his Patterson fellowship, Noé examined the lives of farm workers in the Coachella Valley.