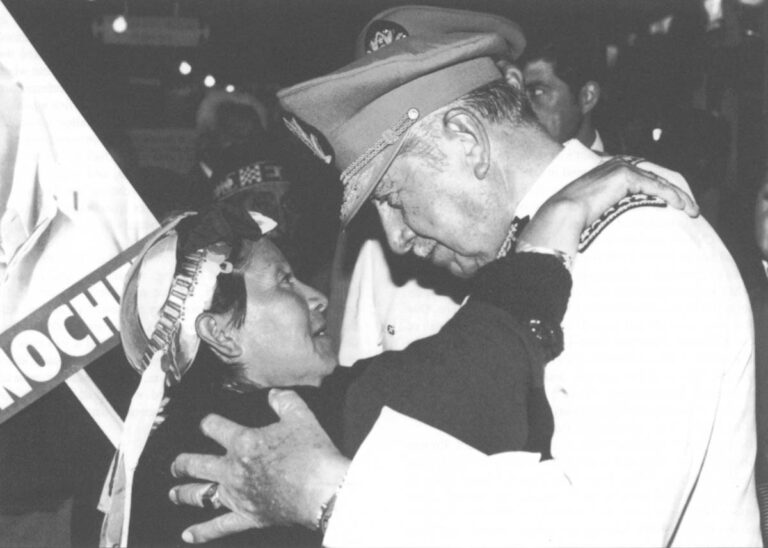

On September 30, 1988, Augusto Pinochet Ugarte was in majestic fighting form. Chile’s barrel-chested, 72-year-old dictator had just nominated himself for president, with the concurrence of his three fellow military commanders, and officials were gathered in a cavernous hall for his acceptance speech. Resplendent in white dress tunic and tri-colored sash, the general rose from a red velvet throne.

In thundering tones, he recalled the “glorious” act that had freed Chile from Soviet “tyranny” with the military coup of September 11, 1973, and the armed forces’ 15 years of dedication to rebuilding society. But he warned that Chileans have “still not freed ourselves from the destructive and dissolute presence of Marxism,” and that his firm guidance was needed to complete the task. “Liberty,” he declared, “must not become the instrument of its own destruction!”

There was no question in the general’s mind that he would be elected in the “yes-no” presidential referendum. Crowds cheered him at rallies, aides had assured him the people were grateful for his sacrifice, and nightly campaign ads contrasted bustling scenes of farms and schools with terrifying images of marauding Marxist thugs. “What is truly at stake,” Pinochet warned in a final campaign speech, “is the freedom of Chile.”

But on October 5th, something went terribly wrong. Waiting patiently in long polling lines, the voters chose, by a solid 56 to 43 percent, to end Pinochet’s reign and hold open elections. The general who had overthrown the world’s first elected Marxist government, then amassed a degree of personal power rare even among Third World dictators, was defeated by an unarmed populace acting within the very legal framework he had designed to perpetuate his rule.

Stunned and fuming in his palace, Pinochet raged that he had been deceived by his advisers and betrayed by the people. But there was nothing he could do. The next night, he appeared on television. Gone was the confident, grandfatherly candidate; in his place was a haggard, aging warrior. “In consonance with my invariable norms of conduct as the chief of state,” he said grimly, “I recognize and accept the verdict expressed by a majority of citizens.”

In victory and in defeat, Augusto Pinochet was the quintessential product of his military breeding: rigid, commanding, fervently anti-communist. But he was also a product of absolute power: isolated, messianic, blind to reality. One set of qualities helped him build and sustain autocratic control over a once-democratic society-the other set ultimately helped topple him from power.

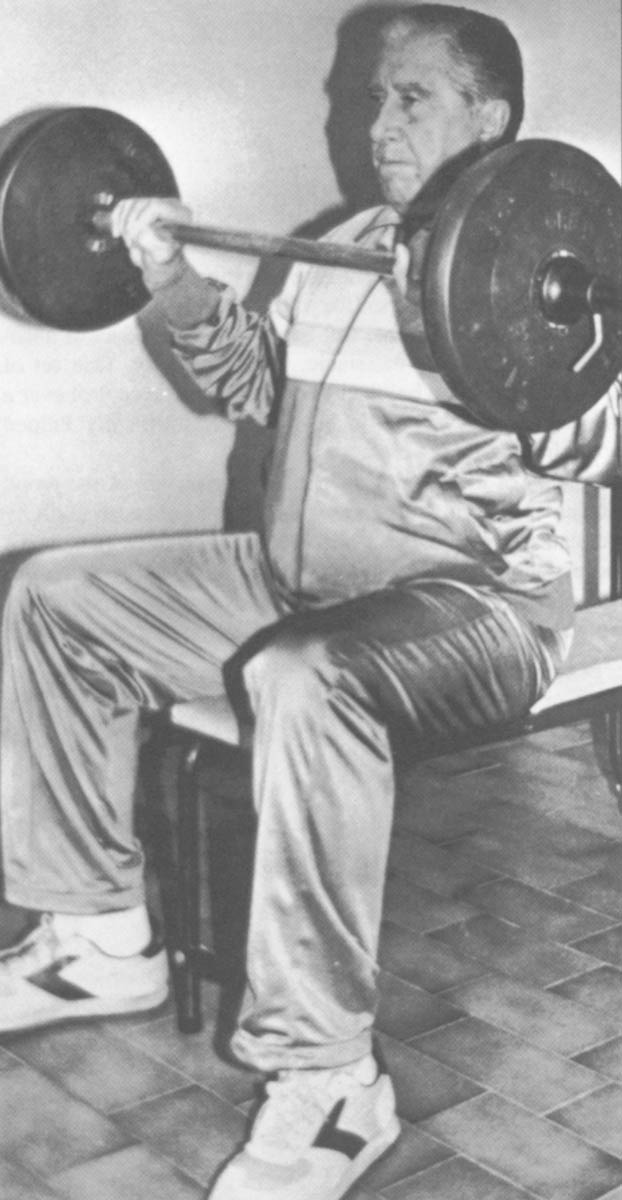

A study of the dictator’s character must begin in the proud Chilean army, which he entered as a teenaged cadet. Built by Prussian trainers in the 19th century, it features parades of goose-stepping soldiers in tasseled helmets, and a system of rigid obedience to superiors. Pinochet was taught that military life was a noble, self- sacrificing vocation, and throughout his career he maintained an aura of Spartan invincibility. On his 70th birthday, he called in photographers to snap him jogging and lifting weights. One former aide described him as “a veritable tank.”

But there was another side to this noble calling. Trained for war, Pinochet viewed the world as a battlefield where political contests were struggles to the death and critics were traitors. “I’m a soldier…for me what is white is white and what is black is black,” he said in 1984. These values were incubated in isolated barracks, cut off from the civilian elites who regarded soldiers as an inferior class. Once he was in charge, Pinochet’s resentment of this comfortable world burst forth. He railed against ‘privileged minorities” and dismissed civilian leaders as unfit to rule. “We are not a vacuum cleaner that swept out Marxism to give back power to those Mr. Politicians,” he declared.

Pinochet’s fervid anti-communism, a political cudgel he used to justify harsh repression as president, also was forged from early military experiences. In the 1940s, the young officer was sent north to guard imprisoned communist “agitators,” then south to investigate party organizing in the coal mines. He described the activists he met as fanatics bent on spreading violence and hatred among the poor. “It was not just another party,” he wrote, “it was a system that transformed them without leaving any belief or faith.”

When President Salvador Allende was elected in 1970, his socialist government brought many Chileans a dream of equality and change. But to others, it brought a nightmare of strikes, slogans and property takeovers. By 1973, many civilians were begging the military to intervene. “We felt the desperation of impotence,” Pinochet recalled. “I felt inhibited from acting, because the instigator of chaos was the very government…to which I owed obedience.”

While Pinochet may have harbored such frustrations, he hid them well from his superiors and colleagues. Allende viewed the taciturn general as unquestionably loyal and named him army commander to stave off rebelliousness in the ranks. At the time, Pinochet later asserted, he was secretly plotting against the government. Officers who spearheaded the coup dispute his account, saying he remained noncommittal until two days beforehand. But once the uprising was underway, the general turned against his government with a fury.

As tanks surrounded La Moneda palace, Pinochet repeatedly demanded Allende’s surrender, then ordered the palace bombed. Striding through the streets in combat gear, he commanded troops as if they were an occupation force. By 6 p.m. a four-man junta was in power, and Pinochet, as head of the oldest military branch, was named its president. Soon, he was describing the coup as a divinely-inspired blow against “Marxist dictatorship,” and the regime’s mission as “extirpating the root of evil from Chile.”

In pursuit of that goal, thousands of Allende’s supporters were herded into sports arenas and interrogated; dozens were shot. Congress was dissolved and newspapers were shut down. A new secret police agency, known as the DINA, began seizing and toturing hundreds of leftists. But when foreigners condemned human rights abuses, Pinochet merely intensified his warnings against Marxist terrorism and dissmissed critics as tools of a Soviet conspiracy against Chile. Many well-to-do citizens, grateful for their “liberation” from Allende’s revolution, ignored persistent reports of repression by a government they believed was defending a holy cause.

At first, the four junta members agreed to rotate the presidency among themselves, and Pinochet asserted, “I don’t want to appear to be an irreplaceable person. I have no aspiration but to serve my country.” But soon his ideological mission began acquiring tinges of personal ambition. Arguing that Chileans needed a single leader, Pinochet persuaded his colleagues to make him the executive, while they would act as legislature. By late 1974, he also maneuvered them into naming him Supreme Chief and President of the Republic.

With a flair for the dramatic and a keen instinct for the power of symbols, Pinochet ordered a presidential sash designed and asked the President of the Supreme Court to bestow it on him. The other junta members were informed minutes before the ceremony. As cameras whirred, Pinochet donned the sash and thanked the judge for an honor “I had never imagined, much less sought.” His colleagues stalked out of the room.

No one in Chile expected the junta to remain in control more than a few years, and by 1978 the other junta members were pressing Pinochet to make plans for the return to democracy. To fend them off, he called a national referendum, without voter registration or pollwatchers. The ballot statement read, “Faced with international aggression launched against our country, I support President Pinochet in his defense of the dignity of Chile and reaffirm the legitimacy of the government.” That night, the government declared a majority had answered, “yes.”

The referendum strengthened Pinochet’s hand against his only rival on the junta, Air Force Commander Gustavo Leigh. After Leigh began publicly criticizing him, Pinochet persuaded the navy and police commanders he had to be dismissed. When Leigh refused to resign, Pinochet ordered him declared “incompetent.” The next day, the air force general found the doors to his office locked, army troops stationed outside, and his colleagues waiting to sign his dismissal. Pinochet’s control of the junta was complete.

The general’s military credentials provided him with more than discipline and muscle. As head of a large army with a tradition of absolute loyalty, he commanded both awesome firepower and iron support. To reinforce his position, he created a new maximum rank of Captain General for his own use, and gradually retired the generals who had engineered the coup or who behaved too independently. In their places, he promoted younger officers and rewarded them with ambassadorships, positions on state corporations, and a vastly improved standard of living.

A second important asset was his stable of civilian aides, mostly conservative lawyers and economists, whom he manipulated and kept off-guard by rotating jobs and creating an overlapping web of advisory panels. A team of legal experts poured out decrees, building a juridical edifice of broad repressive powers and adapting law-abiding Chileans to authoritarian rule. A group of brash young technocrats, dazzling Pinochet with a bold scheme for building an efficient, free-market economy, generated strong support for the regime within the business community.

Finally, Pinochet relied on the vast intelligence apparatus of the DINA, whose director developed files on thousands of individuals and became his closest confidant. Eventually the DINA’s tentacles reached too far, and an inter-national scandal erupted in 1976 when it was linked to the assassination in Washington, D.C. of Orlando Letelier, an official of Allende’s government. Pinochet was forced to rein in and re-name the agency, but its successor continued to practice selective state terror through the 1980s.

As his power grew, Pinochet’s behavior became increasingly autocratic. He rarely appeared in public except for staged ceremonies that gave his regime a feeling of majesty and bounty, filled with cheering recipients of government subsidies. In 1981, with great fanfare, he moved into La Moneda, home to Chilean presidents since 1846. Lavishly restored to erase all traces of the 1973 bombing, it became the ultimate symbol of Pinochet’s pretensions to legitimacy.

While depicting himself as a champion of democracy, Pinochet often expressed admiration for authoritarian rulers. One of his few trips abroad was to attend the 1975 funeral of Spain’s General Francisco Franco, and one former colleague said Pinochet “fancies himself the Franco of Chile.” He also identified with mightier powers, describing his authority as having come from heaven. “I am a man fighting for a just cause: the fight between Christianity…and Marxism,” he said in 1984. “I get my strength from God.”

Despite tense relations with officials of Chile’s Roman Catholic church, Pinochet worked assiduously to manipulate religious symbols. When Pope John Paul II visited Chile in 1987, he infuriated the general by praying for victims of repression. But once John Paul entered La Moneda, Pinochet was in charge. While touring the palace chapel, the Pope turned to find Pinochet and his wife kneeling, and raised his hand. Within hours, photographs of the Holy Father blessing the First Couple covered the afternoon tabloids.

But Pinochet’s exalted notion of himself was accompanied by deep insecurity. He often exploded in rage at subordinates, and if colleagues shone too brightly, he abruptly pushed them from the limelight. His country accent and stiff uniform were easy to lampoon, and he was commonly referred to as “Pinocho” (Spanish for the puppet Pinocchio), but he sternly forbade the press from caricaturing him. “It is a profound error to ridicule my image,” he said. “The Chilean people always respect the figure of the President.”

In his growing isolation. Pinochet trusted no one except a few military aides and relatives, and he surrounded himself with elaborate security measures. Where former Chilean presidents had strolled to work, Pinochet was whisked between appointments in convoys of bullet-proof Mercedes Benz. On September 7, 1986, his paranoia was vindicated when leftist commandos ambushed his motorcade, killing five guards. The general, who escaped with a bruised wrist, declared a state of siege. Hundreds of activists were arrested and four leftist party members were kidnapped and killed, their bullet-ridden bodies dumped beside deserted roads.

Pinochet’s ambitions extended even farther than the desire to rule indefinitely. With Chile’s old political order in ruins, the general sought to create a new one, purged of partisan vices and shielded from communism. The vehicle for this “protected’ democracy was a new constitution, completed in 1980, that banned Marxist parties and ensured the armed forces a permanent role in politics. Pinochet also wanted the charter to consecrate him in office for 16 more years, but when colleagues objected, he agreed to allow a public referendum after eight years-as long as he could run for office again.

To legitimize his constitution, Pinochet called a second referendum. Again, there was no voter registration, and municipal officials controlled the polls. The ballot simply said, “New political constitution” yes or no, and authorities announced that 67 per cent of voters had chosen yes. From then on, whenever his right to rule was questioned, Pinochet flaunted this added mantle of respectability as if its origins were above all reproach.

For more than a decade, Augusto Pinochet controlled Chile through a combination of cunning, ruthlessness and manipulation of economic policy. By the mid-1980s, however, his command began to slip. Spurred by economic recession, students, laborers and housewives took to the streets demanding democracy. Within the regime, officials hinted it was time for change. Pinochet, whose ambitions had become totally intertwined with his ideological mission, ordered student protests quelled with tear gas and ignored widespread demands for open elections or a civilian, “consensus” candidate.

But the general, insulated in his palace and surrounded by flattering aides, made a fatal mistake: he under-estimated the democratic determination of the Chilean people. Pledges of economic prosperity and anti-communist scare-tactics had worn thin, and most voters were far more drawn to opposition leaders’ calls for dignity and democracy. Many of Pinochet’s aides knew he was going to lose, but no one dared report the bad news back up the Prussian chain of command. No one dared to tell the emperor he had no clothes.

Since his defeat, Pinochet–who is scheduled to turn power over to a civilian successor in March of 1989–has argued that his very acceptance of the voters’ verdict was proof of his democratic intentions. Others suggest it was hardly a defeat at all, since he can remain army commander until 1997. But the aging general, blinded by his messianic vision and cornered by his own constitution, has become a tragic figure. The man who hoped to be immortalized as the savior of Chilean democracy was finally outflanked by his true adversary–the people of Chile.

©1989 Pamela Constable

Pamela Constable, on leave from the Boston Globe, is examining the impact of Pinochet’s dictatorship on Chile.