Everyone in Siler City, NC, knows about North Chatham Avenue. They know the street the way one knows a dark secret. Both whites and blacks shake their heads at its mention. Even though the town feels shame about the dilapidated homes that line North Chatham, little has been done. It is accepted like an illegal dump. Nobody likes to see it, but who is going to clean it up? North Chatham Avenue is neglected despite the black eye it gives the town — once the model for The Andy Griffith Show — because it is now home to a growing community of Hispanic immigrant poultry workers.

Finding Candelaria Bahena’s house is difficult because it is tucked behind a side street on North Chatham Avenue. Tall gray slats fence off the dilapidated house she shares with another family. Despite the cold morning, Candi is dressed in jeans, sandals, and a pink T-shirt. Her two little girls cling to her. Candi and her husband both work at the local poultry plant.

“We’ve been here a month,” she says throwing a wave of hair across her back. “Before I lived in a house, but my husband had problems with the landlord.” The family of six was paying $450 a month for a house where the toilet constantly overflowed, the floors were soft, and there was no heat or hot water in the winter. The landlord never made any repairs and when the Bahena family complained, he threw them out with one day’s notice. They found themselves huddled together in a living room in a house on North Chatham, sleeping on the floor as squatters. “Here I am because we can’t find a place to live,” she says.

The large influx of meat and poultry processing workers and their families is creating a high demand for decent affordable housing. Rural communities are failing to meet this growing need. The result is that near slums and ghettos are being formed throughout the South where workers are settling. The meat and poultry industries, for the most part, have been indifferent to pleas from workers and others for better living conditions.

The lack of affordable housing affects workers’ health, safety, and family stability. Because good housing is so scarce, it is not uncommon to find several families or groups of men living in one ramshackle house, each paying rent for conditions few Americans would tolerate. Even under these conditions, some Hispanic workers are buying their first homes, creating a housing boom in some poultry towns.

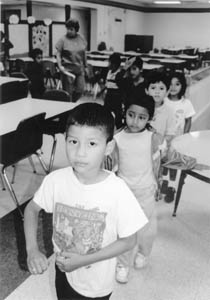

“Housing is a huge crisis and most aren’t eligible for public housing,” says Sally Scholle, a social worker for Chatham County Public Schools. “People are afraid to complain about their living conditions.” Scholle says that housing conditions affect children’s ability to learn. “Children will be tired,” she says. “They have little space especially when getting homework done.”

Housing conditions also can pose a safety issue for children.

“We had a kid who was electrocuted,” says Dr. Susan Pitts, a pediatrician at Moncure Community Health Center. “He had a metal bed with a metal post and the bed was on top of a live wire.” Pitts says the child was shocked when he went to lie down. The child escaped death. This incident happened at a crowded trailer park known as Dreamland in Sanford, NC.

The scarcity of housing leaves families like the Bahenas waiting for something better.

“Housing in Chatham County is pretty non-existent,” says Gloria Sanchez, the Basic Needs coordinator for the schools. “There is no affordable housing and no homeless shelter.” Sanchez’ program helps families who need housing.

With a small budget she can offer families clothes, food, water, and in some cases heating units. But the main problem is finding a place to live. “A lot of families come and they say, ‘Can you find us housing? Can you find us a trailer?’”

The Chatham County Affordable Housing Coalition has tried to get better housing code enforcement in Siler City but quickly found out that enforcement meant condemnations with families being put out, says Andrea Hickle, a coalition member.

As bad as North Chatham Avenue is, the worst housing for poultry workers is an abandoned gas station in Duplin County, Rose Hill, NC.

“Buenas días” Lisa Muñoz says as she raps on the white door of the gas station. There is no answer. Lisa is a minority outreach worker for the Duplin County Health Department. The station, which still has the remnants of the pumping island, has been converted into apartments for poultry workers. Across the two-lane highway, behind chain-link battlements, looms the House of Raeford Farms, Inc., chicken plant. The red and black House of Raeford corporate symbol, fashioned after a medieval crest, hangs on the front gate.

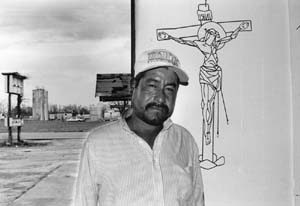

Someone finally answers. Agustin is a short wiry man. He wears a plain white T-shirt and a University of North Carolina Tar Heels cap. He sports a long dark mustache and says he is 35 but looks 45. He is not happy to see us. Muñoz puts him at ease and explains she is from the health department. She wants to know if the people living in the station are okay.

Agustin leads us into the station. It is dark. There is a large living room with an old couch. The cement floor is bare and there are two large plywood panels with padlocks on them. Agustin explains these are their rooms but we can’t go in because there are men sleeping. The kitchen is just a dark hallway. Lisa asks if they have a stove. The answer is no; they don’t need one. “We pay for someone to cook. We’re just men here,” Agustin says. Off to the right are two open rooms. They are bathrooms, the old men and women’s rooms for the gas station. Agustin and his companions pay $60 each in rent, a total of $240 per month.

Agustin is from Zacatecas, Mexico and has been in the U.S. since 1991. He works at the Nash-Johnson chicken plant down the highway catching chickens on the night shift.

He catches eight chickens in each hand, putting a chicken between each finger, two between the first and second and four between his forefinger and thumb. “Seven chickens at times when they take it easy,” he says. He is paid per thousand chickens he picks up from the floor. He says he makes $300 a week, depending on the number of nights he works. I ask him if his hands hurt.

“My hands do hurt, but on me, they hurt here,” he says pointing to the fleshy part between his thumb and finger. “My shoulders hurt too.” He holds his hands out and they are trembling. He cannot keep them still.

Every Friday night, las ninas malas cruise North Chatham Avenue in search of “nice Latin boys.” The women are between 18 and 22-years-old, white, and addicted to crack cocaine. Some are high school grads. They are looking to pull a “straight twenty” to buy a rock of crack, but they’ll take what they can get. Some get so hard up they’ll put out for the change in a man’s pocket. Las ninas malas know which doors they can knock on–the ones where five or more men or boys live alone. They stay away from homes where there are families.

It’s Friday night, payday at the chicken plant, and the “little bad girls” are looking for that first high of the evening. They know enough Spanish to get by, phrases like “Viente dolares, todos sus amigos?” “Twenty dollars, all of your friends?” The teenage boys are away from mama for the first time, the men away from their wives and girlfriends in Mexico. They are lonely and bored. Not much to do but drink lots of beer and open the door when someone knocks.

“The girls love the Hispanics,” says Heidi Farrell, the communicable disease coordinator for the Chatham County Health Department. “They say they make pretty babies. Plus, I think the Hispanic men treat them nicely.”

Chatham County and Siler City in particular are in the midst of a syphilis outbreak because of drug-addicted prostitutes. In 1996, there were only four reported cases of syphilis for the county. By August 1999, that number had risen to 54. Most of these cases were in the white and black communities. The health department is worried about the Hispanic community because the prostitutes said they target those neighborhoods. The department has received more than 300 reported contacts in those areas.

On August 13, 1999, the department and state responded with an intervention program aimed at North Chatham Avenue and other predominantly Hispanic neighborhoods such as Snipes Trailer Park.

“We are spending a lot of time, energy, and money because we know they’re victims,” Farrell says. “They are being preyed upon.”

The intervention had mixed results and the health department still is concerned about syphilis infection in the Hispanic community.

Hispanic poultry workers are vulnerable to other health troubles because of their living situations.

Depression disproportionately strikes females hard. “They’re separated from home, they don’t know the language, they don’t have transportation,” says Maria Lapetina, Ph.D., the only bilingual, bicultural therapist in the county. “They don’t have a support system and they lose their identity.” Many women have left their children in their native land to work at U.S. plants and send money home to support them. “I’m seeing a woman right now. Her husband left her, and she came here and left her kids alone,” Lapetina said.

Many men suffer from anxiety attacks, says Dr. Anju Sharma, who practices family medicine for the health department. He has treated four such men. They complain of chest pains, sweatiness, and panic. “It is pretty uncommon to see that in men in the American community,” he says. “I have two patients who can’t hold a job because of these attacks.”

Domestic violence also is high in the immigrant community. “The majority of women when I ask, ‘Have you been abused,’ they say, ‘Not yet, thank God.’ But a lot of women are abused,” says Dr. Melissa Bishop, a physician at Moncure Community Health Center.

Women are unable to leave violent situations because of the lack of affordable housing. “Because the housing market is so tight, the victims have less options,” says Christy Koch, family peace coordinator for the Coalition for Family Peace in Siler City. The coalition provides domestic violence services, prevention and community awareness programs in Spanish. Koch notes that Hispanic women are hesitant, culturally, to use domestic violence shelters.

But, community awareness of domestic violence has grown and more women are seeking help. The number of new Hispanic clients the coalition has helped has doubled since it began in 1997, Koch says. “Now people talk about it.”

An unknown number of men and women are not married but “juntado,” or hooked up informally. A woman will hook up with a man for financial reasons, lack of housing, or because it is expected for her to be with a man. A man will hook up with a woman in his native country and bring her to the U.S. to take care of him. Many have other wives and children back home. Traditional Hispanic culture centers around the family. The trend of juntados runs against the grain, threatening the stability of families in poultry towns.

The state doesn’t make it easy for couples that are juntado to get married. The state requires a social security number to complete a marriage license application. Couples are afraid their undocumented status will be revealed and so do not get married. Rev. Daniel Quackenbush of St. Julia’s Catholic Church in Siler City, has driven couples across state lines into South Carolina to be married.

Juan Jimenez knows all about North Chatham Avenue. He, his wife Ofelia, and their three daughters, have lived in a dilapidated house there for years. “If you were to see where I was living before,” he says shaking his head. “Here, we’re in the glory, but before, I lived with nothing.” Today, he lives in his own house with a $550 monthly mortgage.

Juan is one of many poultry workers who are increasing home values and interest rates in Siler City. This is good for old-time residents wanting to sell, but prevents immigrants from buying.

Three years ago, a two bedroom, one bathroom house sold for about $39,000, according to Holly Kozelsky, a bilingual agent for Dowd & Harris Realty, Inc., the county’s largest real estate firm. Today, that house would sell for $59,000.

In the spring of 1999, interest rates were 6.76 percent. Today, they hover at 8.5 percent. A poultry worker making $7.50 an hour, or a yearly income of $14,400, cannot afford a house at 8.5 percent, according to Kozelsky.

“Last year, I was selling to single family breadwinners, and now, they’re finding they can’t afford a house on just one income,” Kozelsky says. “Two income families may even be stuck with a two bedroom house when they need three bedrooms.”

Hispanic families have responded to higher interest rates by doubling or tripling up on a home purchase. This makes it harder for single-family breadwinners to buy a home. “The solution is part of the problem with housing,” Kozelsky says. “Prices have been rising astronomically and they’re priced out.”

Juan considers himself lucky to have bought his home. “We’d still be living on North Chatham Avenue,” he says picking up his daughter. “This is a dream.”

When Candi was dreaming of owning a home, she and her oldest boy, Nelson, 11, who speaks English, inquired about renting a mobile home. The owner of the trailer refused to rent to her because she has too many children. He struck a cruel deal.

“The man said, ‘Sell two of your children and then you’ll only be left with two and I’ll rent you the trailer.’ But he said that smiling at the air, like a joke. I feel bad because they’re my children and I won’t give them away or sell them.…”

I asked Nelson how he felt translating the “joke.” He shrugged his small shoulders and turned away.

Candi and her family finally moved from North Chatham Avenue a few months later. They had no furniture and the house was not in good shape. The floors were cracked, peeling, and uneven. The yard was just dirt. At least the toilet worked. But the house was theirs and they were far away from North Chatham Avenue.

©2001 Paul Cuadros

Paul Cuadros, a freelance writer, is living in North Carolina while examining the impact of Hispanic workers on Southern meat and poultry towns.