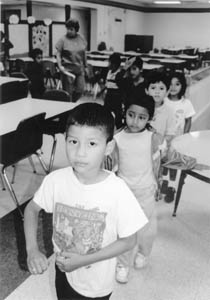

Everyone’s time is set to four thirty in the afternoon in Siler City, North Carolina. It’s the hour when everyone comes home. Children come home from school and toss their backpacks on the floor. Parents come home from the chicken plants and leave their black boots on the doorstep. And Maria comes home and picks up her nine-month old daughter from the babysitter next door.

Before she steps into the shower to wash the day’s chicken grease and smell from her body, she prepares her baby’s bottle. The bottles and formula are laid out with care on the kitchen table in her single-wide trailer. The mobile home is neat and clean. There are two large sofas and a giant black television in the living room. The walls are wood paneled making the room dark and quiet.

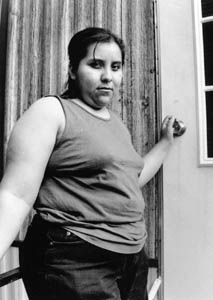

Maria puts her blue helmet away and pulls off the hair net. She cradles her baby. She is shy and unaccustomed to talking about herself. She does not smile as much as offer a sly little girl grin, her head tilted, her brown eyes coming around their corners.

Maria, like many immigrant mothers working in the poultry industry, does not breast feed her baby. She does not have the time. “What happens is, because you have to go to work, it’s harder to breast feed her and she gets used to it,” Maria says peering through a single black brush stroke of hair covering her face.

Maria and her baby have gotten used to a lot of things because of her job at the poultry plant. She’s missed prenatal appointments so she could keep her job. She’s missed appointments when she couldn’t find a ride to the clinic. She’s missed appointments because she doesn’t make enough money. She’s been confused at the clinic because she could not speak English. And, finally, because she is undocumented, she’s worried she would not be able to claim the poultry company’s maternity benefits.

Maria and her baby are not alone in facing enormous barriers in the way of good, affordable health care. Recruited and coaxed by poultry plants, Hispanic immigrant families have flooded Southern rural counties in the past six years. Their increasing numbers and special needs have strained health care services in rural counties forcing health care providers to adapt the way they administer care.

But even though they are trying their best, the challenges are overwhelming.

Poultry workers, like Maria, face many barriers to seeing a doctor, including, for many, their undocumented status, expense, transportation, and not being able to speak English. Job conditions at poultry plants, such as limited sick leave and a demerit system for unexcused work absences, also conspire to frustrate access to care for workers. As a result, North Carolina’s Hispanic immigrants, at best, have only limited and conditional access to health care.

Of all the obstacles to health care for both patient and health care worker, none is more frustrating than not being able to communicate.

“Many other providers haven’t stepped up to the plate in providing Spanish-speaking providers,” said Dr. Barbara Rowland, medical director of Piedmont Health Services, Inc., which operates three community health centers, including one in Chatham County where Maria lives.

The lack of bilingual providers and interpreters forces many families to rely on their English-speaking children or travel long distances for health facilities that provide them.

“Any situation where a child is an interpreter is risky,” said Elia Sustaita, one of six on-call interpreter for Chatham Hospital in Siler City. “They may not understand what’s going or have the vocabulary to explain what the doctor is saying.”

“A lot of people will either move here or say they live here because we don’t charge for interpreters,” said Sue Fields, an obstetrics, gynecology nurse practitioner for the Chatham County Health Department’s clinic in Siler City. The clinic has two interpreters.

But many health departments offer no interpreters.

In a survey of 218 health providers in North Carolina, including all the state’s health departments, community and migrant health centers, rural health centers, and rural hospitals, 43 percent of the 168 providers who responded said they ask clients to bring their own interpreters.

The Office of Civil Rights of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services requires that any health care facility receiving federal funds offer free interpretation services. Despite receiving federal funds, half of the state’s 87 health departments ask clients to bring their own interpreters. The survey was conducted in 1999 by the North Carolina Center for Public Policy Research in its report, “Hispanic/Latino Health in North Carolina, Failure to Communicate?”

Private physicians are also feeling the need to provide interpreters or bilingual staff to facilitate communication and improve health care. Dr. James Schwankl, a pediatrician in Siler City, said his Spanish-speaking clientele has grown since adding a bilingual staff person.

But while interpreters help they do not solve all the communication problems.

“We miss the cultural context,” said Dr. Anuj Sharma, a family medicine doctor for the county health department and a physician at Chatham Primary Care, a University of North Carolina health care clinic in Siler City. She said there are certain words that cannot be translated. “I explain things, but I am never sure if they understand what’s going on.”

Confusion can be a problem for both the patient and the doctor who are unable to connect. “It’s hard to establish a relationship with a doctor through an interpreter,” Dr. Rowland said. Interpreters are also costly. “If you have to translate, then that takes time, and that reduces the number of people we can serve. We make money servicing.”

Dr. Rowland believes that bilingual providers are a better solution. Piedmont has three Spanish-speaking doctors at its Moncure Community Health Center in Chatham County. “If you have the bilingual staff, they will come.”

And come they have. Hispanics made up only two percent of Piedmont’s users in 1989 and now compose 27 percent. “Our pregnant women are 60, 65 percent Latina,” Dr. Rowland said. “That corresponds to a huge number of visits.”

But speaking Spanish is not enough. That’s because many poultry workers are undocumented and work at the plant under an alias.

The first thing Maria thought of when she found out she was pregnant was how was she going to keep her job. Maria had a problem. Maria is not Maria at the plant. She works under a different name there, her work name. How was she going to get maternity leave under her work name?

“I think everyone knows that the people work without their real name,” Maria says.

An unknown number of poultry workers are undocumented and find work using aliases and fraudulent documents. The different identities of workers and their fear of being discovered complicate and make administering care difficult. As a result, some health care providers will accept an alias or look the other way, and others will not. This puts up another roadblock for access to care for undocumented poultry workers who must find a health provider favorable to their situation. If they can’t, they could lose their job or not receive benefits like maternity leave. For pregnant women, the situation is even more dire because they want their babies to born with their real names, not their aliases.

Maria lost her first job at one of two poultry plants in town when her alias was discovered. After six months she found a new job at the other plant in town. Now she needed a doctor to write her a medical note saying she was pregnant so she could get maternity leave and not lose her job again. The doctor needed to put her work name on the note despite knowing her real name. She knew she couldn’t go to the health department.

“We, as a health department, have decided not to sign papers or fill out forms in another person’s name,” Fields said. “That applies to insurance papers like short term disability for being out of work or for maternity leave.” Fields added that workers can become so desperate that they have tried bribing interpreters at the Siler City clinic for $200 just for the note.

The only place, it seems, where Maria can get a medical note saying she’s pregnant under her work name is Piedmont’s Moncure Health Center, some 30 miles from where she lives in Siler City. The center is a community health care organization designed to serve underserved and poor populations. Pregnant and sick workers make the trip just to get that note.

“That’s why they all come to us from Siler City,” said Dr. Melissa Bishop, a family medicine and prenatal care physician for the center. “We see people coming here eight months into their pregnancy and getting the work note and they never come back. They want that work note.”

Dr. Rowland said it is not their job to verify the immigration status or identity of her clients. “Sue me.” she said. “My job is to provide health care.” She added that the poultry companies bear the responsibility for employing undocumented workers, not the health centers.

The health department sticks with whatever name the patient presents during the visit. But they will not falsify information if they learn of another name. “If they register under a certain name, that’s who they are,” said Wayne Sherman, director of the health department. “We felt, under a legal standard, that we would not falsify information.”

Even with the maternity excuse, female workers do not take their full leave. Maria says that the first poultry plant where she worked allowed 12 weeks for maternity leave, a month before delivery and two months afterwards. She went back to work early because the company only paid 60 percent of her salary. “I came away with $160 a week,” she says. She was making $365 with overtime.

Many poultry processing plants do not pay when their workers are sick. Victorino, a poultry worker in Chatham County, went two weeks without pay while doctors performed tests to determine if he had active tuberculosis.

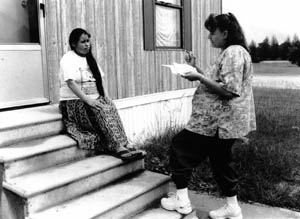

“A lot of Hispanics are afraid to miss work so they don’t come to the clinic until it is too late,” said Lisa Munoz, a health outreach worker for the Duplin County Health Department. She knows of one little girl who has partial hearing loss because her mother waited to bring her daughter in after an ear infection. “What happens is in the larger plants, the chickens, turkeys, hogs, is they are allotted three times to miss work. A lot of people do not want to use up their times even though they may have a terrible cold.”

When companies do provide sick leave, workers are reluctant to take it. “The women take it upon themselves not to come in because they don’t want to take two hours off,” Munoz said. “Everything falls back to, ‘I don’t want to miss work because of the money.’”

Workers are careful not to get medical notes in their real names for fear of forcing poultry plants to fire them. Plants would rather not know for certain.

“They know they’re illegal. Everyone knows,” Fields said. “But they only have to look at the identification they bring in. Once they know for sure someone is illegal, then they dismiss them. They have to.”

The alias issue has had a chilling effect on health providers who want to serve this population but are afraid of the legal issues.

“It makes me feel uncomfortable,” said Dr. Sharma. “In a way it’s fraud. I get a sense of uneasiness.”

“That’s what has a lot of doctors afraid to expand their services to immigrants,” said Bill Lail, chairman of the Chatham Family Resource Center in Siler City. The center is a non-profit agency that was created in 1994 by the health department to provide health and community education programs for immigrants.

The illegal status of the immigrants also affects how providers administer care and the quality of care.

“The clinic is busy and if we have to stop and screw around with names, that’s really time consuming,” Dr. Rowland said. “There are a lot of aliases. People are changing their names. We’ve got people with two or three charts. It’s awful.”

With so many aliases floating about, tracking patients can be a problem. Continuity of care also can suffer because doctors do not know what other doctors have prescribed for the same patient. Aliases also affect private physicians like Dr. Schwankl who said the different names makes filing histories difficult. “It’s an issue of confusion sometimes and frustration too,” he said.

Health care providers have learned to create systems around this problem.

“We can combine two charts,” Fields said. She said that workers who are screened at the poultry plant for TB under their work name come to the health department and use their real name. “So, we create one chart with two names in them.”

The undocumented status of workers also affects how they pay for services and how providers charge for service.

Maria received Medicaid during her first two months of pregnancy. Even though she is undocumented and thus does not qualify for the program, she was able to get two months of care covered. This is because Medicaid allows designated health providers to presume all pregnant women are eligible for two months so they can receive immediate care. This is called “presumptive eligibility.” After the two month period, women must apply to the program to receive full Medicaid benefits.

Many undocumented pregnant poultry workers receive Medicaid coverage under presumptive eligibility. Presumptive eligibility not only covers the patient but also reimburses the health provider with Medicaid funds for the costs of administering care.

An analysis of presumptive eligible recipients in North Carolina shows an explosive growth of Hispanic women using the program from 1992 to 1998.

In 1992, according to the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, there were 53 Hispanic women on presumptive eligibility compared to 18 white women and 9 black women. By 1998, the number of Hispanic women using presumptive eligibility increased to 3,046. The number of white women increased to 417, and the number of black women to 219. Hispanic women make up 83 percent of all women on presumptive eligibility in 1998. The total number of Hispanic women on full Medicaid has also increased from 2,452 in 1992 to 26,940 in 1998.

Rural counties with poultry plants have seen an increase of Hispanic women on presumptive eligibility from 37 in 1992 to 1,464 in 1998. Hispanic women in rural poultry counties make up almost half, 48 percent, of all Hispanic women on presumptive eligibility. And, Hispanic women in rural poultry counties account for 40 percent all women on presumptive eligibility in the state.

In Chatham County, there were only 4 Hispanic women on the program in 1992. By 1998, that number increased to 110. There were only 4 white women and 11 black women on presumptive eligibility that year.

In nearby Lee County, presumptive eligible Hispanic women jumped from 4 in 1992 to 138 in 1998. And in Duplin County, Hispanic women increased from 2 in 1992 to 112 in 1998.

Many county health departments did not offer presumptive eligibility to poor pregnant women because they normally qualified for full Medicaid benefits. But that changed when the Hispanic population began to increase and the number of undocumented pregnant women rose. Counties then began to ask the state to train them in presumptive eligibility.

“When they started seeing large numbers of undocumented folks and they knew those people might not be eligible if they made full application, they said, ‘come and do a refresher training because we want to start this presumptive eligibility,” said Lynda Dixon, the state’s Baby Love program coordinator which oversees Medicaid programs.

The vast majority of poor Hispanic pregnant women on presumptive eligibility are undocumented, an analysis of state Medicaid records shows, making them ineligible for full Medicaid coverage.

Of the 1,489 total Hispanic women whose income is equal to or less than 185 percent of poverty identified as receiving presumptive eligibility in fiscal 1999, 1,479 were later identified as being undocumented. The majority of Hispanic pregnant women in other social health service programs were also undocumented. A total of 1,518 Hispanic pregnant women or 85 percent were later identified as undocumented out of a total of 1,785 women in a variety of public assistance programs including Work First, and Medicaid for legal aliens. A closer look at Hispanic women and Medicaid programs, reveals that 1,723 Hispanic women, or 96 percent, were either initially or later identified as undocumented out of a total of 1,785 women in fiscal 1999.

The figures for Medicaid presumptive eligibility are the first to disclose how large the undocumented Hispanic population is in North Carolina. While it is not a full count of the number of undocumented people who have moved into the state, it does provide a glimpse of how large the undocumented population may be.

Dixon said that it is not the responsibility of health departments or other providers to determine legal resident status when it comes to presumptive eligibility. But many health departments and providers know this population is undocumented and not eligible to receive Medicaid. Presumptive eligibility is a federal loophole that has helped thousands of pregnant undocumented women receive care and offset costs for struggling health providers, if for a short time.

The impact of the increase in this population has been felt hardest by county health departments and other community health providers. They have seen their Medicaid eligible population fall and their undocumented or ineligible population rise. The result is they must absorb the cost of an increasing population with no federal reimbursements.

“Health departments are left with the people who have no eligibility for Medicaid which is the undocumented population, and in some counties, that’s all that’s left,” Dixon said. “That’s a problem for them as how to continue to serve them with no reimbursement.”

Health departments and community providers have had to become creative with the reimbursements they do receive for undocumented pregnant women under presumptive eligibility.

Different health providers bill presumptively for Medicaid at different times during a woman’s pregnancy to maximize benefits and care.

The Chatham County Health Department waits until the last two months of pregnancy before they bill presumptively for Medicaid. “We get more money because they come in every week the last two months,” Fields said.

Typically, if they have no health insurance, poultry workers pay a sliding scale fee at the health department. Most of the patients fall between 0 and 40 percent on the sliding scale, said Cynthia Joyce, director of nursing for the department.

Presumptive eligibility helps the provider recover costs associated with prenatal care. The health department could use the help. It has seen revenues fall. “We’ve seen a decrease in Medicaid eligible clients as we’ve seen an increase in our non-Medicaid eligible clients,” Joyce said. She added that the Medicaid system is partly responsible for this as more private providers are accepting Medicaid. The drop in Medicaid eligible clients and rise in non-eligible clients mirrors the drop in African Americans clients and the increase in Hispanic clients.

Moncure Health Center also bills presumptively for pregnant workers. “Our system is to do it when they first show up and pay for their labs and possibly their ultrasounds because a lot of women need ultrasounds in the first trimester,” Dr. Rowland said. She said the ultrasound could be expensive because it is performed at a hospital. “We try to time it around the ultrasound which is usually around sixteen to eighteen weeks,” she said. “It’s more expensive for the patients because it’s not done at our clinic, it’s done at a hospital and they get billed, there is no sliding fee scale.”

Moncure sees a great number of undocumented pregnant workers and the number of presumptive eligibiles has increased. While the clinic is reimbursed for its costs, it is not getting ahead.

“This is small potatoes money to us,” Dr. Rowland said. “I might see them once, maybe twice on presumptive eligibility. It would be a big drop in the bucket if you could plan so that they could have their presumptive eligibility when they had surgery or something.” She added that it also costs the clinic money to bill this way.

The health department and the center make out when the children are born. They qualify for Medicaid and are placed in the program for 13 months.

“While the mother may never be on Medicaid, her baby will and then there’s a lot of visits for that newborn,” Dr. Rowland said.

Hispanics only make up 11 percent of the Medicaid population in Chatham County, according to the Chatham County Social Services. The vast majority, 92 percent, are 18 and under. Women between 18 and 44 make up the next biggest group at 6.5 percent. The largest group on Medicaid in the county is whites who make up 44.5 percent of all recipients. White women are the largest single group of Medicaid recipients.

Even though the babies are put on Medicaid when they are born, they don’t stay on it for long. Many Hispanic parents do not reapply for Medicaid after the 13 months.

Many more poultry workers are now receiving health insurance benefits from their employers. But an unknown number are unable to access insurance because of their alias even though they pay for it.

“Although they have health insurance at work, they’re working under a different name,” Joyce said. “When we access it and we see a different name, we can’t use their insurance. They (the insurance company) could get us for fraud.”

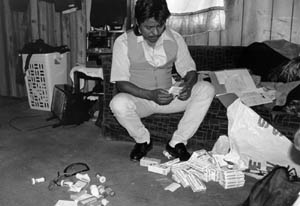

Juan will never be the same after the accident. A cleaner at a chicken plant in Chatham County, he slipped and fell, spilling four buckets of cleaning chemicals and mixing them into a dangerous gas.

“I didn’t feel anything,” he says. “I was going to throw water on it when someone said, ‘run!’ because it’s dangerous gas.” Juan didn’t make it far. He got dizzy and collapsed. He woke in the hospital. The August spill forced the evacuation of the entire plant just as the first shift was starting. In all, 29 people were sent to the hospital.

“My head hurts a lot, day and night,” he says. There is blood in his urine, he can’t stand up for more than a few minutes without becoming dizzy, and he has headaches. He has not worked or been paid since the accident. He is two months behind on his rent and friends bring him food to eat. He has since filed for worker’s compensation but he doesn’t care about the money. He just wants to get better. He partially blames the company for not properly labeling the contents of the buckets. He didn’t know they contained deadly chemicals when mixed.

Worker injury is a problem in the meat and poultry processing industry. It is a dangerous job. Workers can get hurt through slips and falls, cuts, and through repetitive motion injuries like carpal tunnel syndrome. Many workers suffer from terrible foot fungus. When workers do get hurt, the system is stacked against them, especially if they’re undocumented.

“Usually when a worker gets injured they try and soft peddle the situation,” said Robert Willis, an attorney who handles worker’s compensation claims. “They steer you towards the short term disability program, a non-worker compensation insurance program. Then they’ll have you fill out a form that says the injury is not work related. And there goes your case.”

Companies use the system to keep a worker working despite his or her injury. A person who may be totally disabled with carpal tunnel syndrome is sent to a place like the box room where they can keep working until the statute of limitations for worker’s compensation runs out. Then they’re told to go back to the cutting line. When they can’t work, they’re fired.

“Time works against anybody in a poultry plant,” Willis said. “If you get a work limitation they’re always chipping away at the limitation.” Raquel received a work limitation when she slipped and fell in a chicken plant in Siler City. She ruptured a disk in her spine. The doctor told her to work half the day sitting and half standing. The company agreed to the limitation, but when Raquel sat down, a supervisor told her to keep working standing up. Eventually, she was fired for insubordination.

While there are many barriers to health care for the Hispanic immigrant population, sometimes just getting to the doctor can be the toughest obstacle.

Rosa Maria lives on hope these days. She is alone. She lives in a trailer with five men who work for Carolina Turkey in Duplin County. She cooks and cleans the trailer for them. In return, they let her stay in the trailer, which the company manages.

She came to Duplin County in search of a new life. But she didn’t know she was pregnant when she crossed the border. Now, she can’t find a job.

Rosa Maria has no idea how she will get to the hospital to deliver her baby. She is relying on the good will of her neighbors in the trailer park.

“Well, my plan is to ask for a ride around here,” she says. The trailer park is isolated and located far from the nearest hospital in Kenansville. When pressed that it may be difficult to ask for a ride when in labor she responds, “Some people around here, they work during the day, and some work at night, and the ones who work at night can give me a ride because it’s only a half hour.”

She is a small woman. Her dark straight hair is long, falling to her waist. She has small eyes and a wide mouth with gold capped teeth in the front in a jaw that juts forward. She smiles and laughs easily despite her predicament. The men will not allow her to stay once the baby comes.

Transportation to health care facilities can be nonexistent for some food processing workers and their families. Women and children will miss appointments or delay going to the doctor because there is no one to take them. Many women do not know how to drive.

“The women don’t want to be burden on the men,” said Lucia Merino, a social worker and former maternity care coordinator in Chatham County. “They don’t drive and the men don’t teach them.” She said that even if a facility provides transportation, the family might not have a phone to call them.

Some health care providers have responded to this problem by creating their own transportation service. Moncure Health Center has a van that will pick clients up in the morning and drop them off in the afternoon.

Rosa Maria had her baby at the hospital in Kenansville. She was lucky enough to find a ride that day.

©2001 Paul Cuadros

Paul Cuadros, a writer with the Center for Public Integrity, in Washington, D.C., is researching the changing fabric of Southern poultry towns.