Luis sits at a computer working with a program designed to teach him English. He is warm and accepting, still trusting despite what he has seen. But when the 11-year-old recalls his journey from Guanajuato, Mexico to Morganton, North Carolina, his round face darkens and his eyes contract with fear. It was a bad time.

“Walking through Texas, I think is very hard work to walk and run on the dirt. You can fall. It is so bad that it is enough to make one want to cry,” he said as he sat in Hillcrest Elementary School.

The trip took 15 days and the family was separated as they dodged federal authorities. His family traveled by bus from Guanajuato to the border and then waited in a hotel for their “coyote” to guide them. A coyote is someone who leads undocumented people into the country for a fee.

“At times we separate. Like, my father, goes off with another group, and my mother, with another, and I go with another. For ten days. That’s very sad.” Luis spent two days walking until authorities caught and returned them to the border. His family then walked for four days before being re-caught. On the third try, after eight days, they made it through.

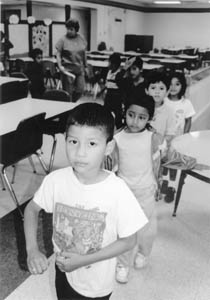

Luis’ family arrived in Morganton in January. They traveled hundreds of miles and risked their lives for the chance to cut chickens at the Case Farms poultry processing plant. They are not alone.

Immigrant workers and their families, many undocumented, are now settling in rural poultry and meat packing towns in North Carolina and other Southern states. Once coaxed by poultry processing worker incentives and industry recruitment, they are now drawn by a word-of-mouth pipeline that has pumped thousands of immigrant families where there once were few. The result has been a tremendous cultural and social impact on rural towns. Classrooms are the epicenter of this change.

“We have many places that had no immigrant children five, six years ago that now have those children,” said Fran Hoch, section chief for the Department of Public Instruction’s English-as-a Second Language program.

The population increase is straining local school systems that are desperate for ESL-certified teachers, materials, and space to accommodate these children. Schools also struggle with a myriad of social problems, placing the heaviest burden on ESL teachers. Compounding the problem, the state has been slow to provide funding. New accountability tests for schools and students may condemn immigrant students to repeat grades or failure. The amount needed to help may reach as high as $80 million statewide.

The impact of immigrant workers and their children began to be felt five years ago. But change was in the works years before.

The processing industry went through dramatic changes during the 1970s and 1980s. Processors adopted a disassembly line method, moved their plants to rural communities to smash unions, and gobbled up smaller companies. Poultry surpassed beef in meat consumption in the 1980s, spurring growth, said David Griffith, an associate professor of anthropology at East Carolina University. The demand for line labor also increased as chicken was sliced into ready-made dinners and deboned pieces, reducing the need for supermarket butchers.

These factors increased the demand for cheap labor and immigrant workers answered the call. Many meat and poultry processors turn a blind eye when it comes to the legal status of their workers.

A robust economy has increased the demand for workers. African-Americans, a traditional labor force for poultry, experienced the lowest levels of unemployment since the 1970s.

Companies began recruiting outside the country. Beef packers set up trailers along border towns in Texas to entice and recruit new workers. Others recruited inside the country, picking up migrant farm workers. Case Farms in Morganton, N.C. went to Florida to recruit Guatemalans. Tysons Foods relied on word of mouth and incentives for their recruitment.

“We had something called a buddy bonus that if you brought a new employee and they stayed x amount, you got x amount of dollars and a coupon,” said Barbara Berry, former human relations director of Tysons Foods. “We did a lot of innovative things trying to have people spread the word.”

That word has spread to the point that processors no longer need to actively recruit. Now families, like Luis’ make their way to Carolina del Norte for poultry jobs. Once there, they buy false papers, start work, and enroll their kids in school.

Stephanie Scarce stands against a locker at Chatham Middle School watching her last ESL class run to the yellow school buses. She is a magnet in the hall attracting Hispanic children who rush to her, hug her, clutch her. She throws her arms around them, returning their affection. She is a blur of energy.

Scarce came to Siler City, a small town in Chatham County that boasts two poultry plants, in January 1998, by chance. She was teaching Spanish at a local community college and the school was desperate for an ESL instructor.

“They couldn’t find anyone bilingual and they can’t find anyone who can teach ESL,” Scarce said. “They didn’t have anybody in the school who could speak Spanish. Nobody to handle the discipline problems. Nobody who could speak to the parents. Nobody to handle the counselor problems. It’s an enormous problem for Siler City and they are scrounging around to get things together.”

The Limited English Proficient student population in Chatham County increased from just 80 students in 1990 to 458 in 1998. Siler City Elementary is now more than 40 percent Hispanic. The kindergarten class is more than 50 percent Hispanic.

Chatham County is not alone. The state has been hit with an influx of LEP students and counties with poultry plants have seen the fastest growth. The state’s LEP population increased from 12,452 students in 1993-1994 to 28,704 students in 1997-1998, state LEP figures show.

These kinds of increases can be found throughout the state, especially in counties with poultry plants. In Burke County (260 percent), in Lee County (132 percent), in Bladen County (165 percent). The state’s LEP population has grown by 25 percent each year for the past five years, according to the state’s department of education.

Rural poultry counties saw their LEP populations increase from 3,994 students in 1993-1994 to 9,316 students in 1997-1998. And the rural poultry counties’ LEP population makes up almost one third, or 32 percent, of the entire LEP population in the state.

“Teachers were extremely frustrated because they didn’t know how to teach the students,” said Charles Johnson who directs the ESL program for Chatham County. “The population was growing at such a rate we didn’t have enough ESL teachers.”

Chatham currently has seven ESL teachers and four ESL assistants. But some ESL teachers do not have their ESL certificate and some have no teaching certificate.

“We have one like that now,” said Linda Higgins, director of special programs for Lee County Public Schools. Of the 13 ESL teachers, only five are certified. The majority are working toward certification.

Burke County has 11 ESL teachers. “We have about half that are certified and the other half working on it,” said Joel Hastings director of exceptional children and ESL for the schools. Bladen County has no ESL teachers and is relying on their Spanish teachers and high school students to pitch in. “It is just frustrating for the teacher to death,” said Ann Elks, assistant superintendent of curriculum for Bladen County Public Schools.

When asked what schools need to help these students the answer is unanimous: funding.

Last year, the General Assembly allocated $5 million in recurring funds for ESL personnel and materials. But the General Assembly had to be dragged, sued, and cajoled into doing it. That has changed.

“What we heard this time around is how much and when we can fully fund it,” said Higgins, who is also president-elect of Carolina Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages, which lobbies the legislature.

This year the General Assembly passed an additional $5 million in recurring funds. But is it enough?

“No, it’s not enough and I think everyone including members of the General Assembly recognize that,” said Greg Malhoit, executive director of the North Carolina Justice and Community Development Center. His organization sued the state in 1994 on behalf of LEP parents, charging it was not educating these students.

Both the justice center and Carolina TESOL are advocating $29 million or $1,000 per LEP child in recurring funds. But even the $29 million will not cover the state’s LEP population if it continues to grow another 25 percent in the coming year.

“We’re just making small baby steps, “ said state Senator Howard Lee who has spearheaded ESL funding efforts in the General Assembly.

The extra $5 million will be a help to counties with large LEP populations, but rural counties with small populations will have a tougher time and they may need the most help. Burke County received more than $250,000 this past school year, Chatham got $87,000, but small Bladen County only saw $14,000.

“What can you do with $14,000 with a hundred kids spread out over 14 different schools?” Elks said. “Fourteen thousand is about half enough to hire a teacher.”

Sen. Lee said that ESL funding is only part of picture. The state will need money to create and foster the supply of ESL teachers at universities and colleges. “In addition to putting money in to help local school districts, we now have to think about putting money in to assist the universities with identifying, recruiting, and training people or finding a way to provide incentives.” He said that adequate funding is $50 to $80 million.

North Carolina is not alone. Alabama and Missouri saw a 200 percent increase in their LEP population from 1992 to 1997. Arkansas had a 481 percent increase and Georgia had a 179 percent increase, according to a 1999 report released by the Southern Legislative Conference of the Council of State Governments in Atlanta.

Missouri has serious trouble. The state’s Department of Elementary and Secondary Education found that 775 students, or ten percent of the entire LEP population, are “either not being served or are receiving something other than services recognized as effective in developing English language proficiency.” Missouri’s increase occurred with the consolidation of smaller poultry companies by giants like Tysons and Cargill, which increased production. “Since that’s happened we’ve seen the growth,” said Joel Judd, Missouri’s ESL coordinator. He added they did not have enough ESL teachers— only 200 statewide to serve a population of 7,217.

The federal government has not been much help. The U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Bilingual Education and Minority Language Affairs gave North Carolina $2.2 million in fiscal year 1998. Missouri received $1.1. million. Georgia only saw $713,311.

As if these obstacles weren’t enough, the North Carolina General Assembly passed the ABCs of Public Education in 1996. It is an accountability model for schools and teachers based on the performance of their students on standardized tests.

The state sets standards for each school’s scores based on the previous year’s performance. Certified staffs in schools that show exemplary growth receive bonuses of $1,500. Low performing schools receive no bonus but get assistance from the state. A student accountability model is set to begin in two years that will hold students accountable for their scores. Low scores for these students mean holding students back or no high school diploma.

LEP students are exempt from these exams for two years. They are allowed to be tested in a separate room, given extra time, and can have teachers read the test aloud.

Many immigrant children have had little formal schooling and face high hurdles in learning a new language quickly and performing on tests. While they easily pick up social English, academic English can take seven years, or longer, to master.

It will be tough on schools with large LEP populations who want the incentive money and want to avoid the stigma of being a low-performing school.

“It’s not fair to the kids and it’s not fair to the school,” said Randy Johnson, principal of Siler City Elementary. Johnson believes the exemption period is too short. Siler City Elementary did not receive a good rating on its ABCs scores this year.

While the state allows LEP students to be promoted for two years for the student accountability tests, the period does not include graduation from high school.

Scarce is blunt about students’ chances. “They’re going to drop out when they reach high school,” she said. “That’s a fact. They can’t make it. If they move here at elementary and middle school level they have a chance.”

The number of LEP dropouts has increased every year since 1995-96 and this year the number reached 554 students. Despite the increasing numbers, the state said the percentage of LEP dropouts to the entire population has been decreasing. But it is not certain whether this is due to younger LEP children entering the system rather than of older students who are more likely to drop out.

Excluding LEP students from tests may also hurt them because the tests pressure schools and teachers to focus attention on them to do better.

But teachers and schools may already be exempting LEP students, or Hispanic students, in general, hiding them to raise scores and earn those bonuses.

The influx of immigrant’s children is causing other changes. When a charter school opened in Siler City two years ago, many white parents removed their children from the elementary school out of fears their children would receive less attention than the LEP kids.

That trend continues. At Siler City Elementary the white and black student population has been dropping due to transfers to other predominantly white schools. In 1997-98, there were 221 white students and 244 black students. As of September 1999, there are 150 white students and 215 blacks students. Students are not only ones leaving the school. Last year, the school lost 15 teachers who transferred elsewhere.

Frustrations and resentment toward the increasing Hispanic students and low ABC test scores finally erupted at a recent school board meeting when angry white and black parents blamed the Hispanic community for diminishing the school.

Kay Staley, a grandmother whose three grandchildren recently transferred out of Siler City Elementary, read a prepared statement. “Maybe they need their alternative schools until they learn English and then we’d be glad to have them come to this school system,” she said. “It’s not our place to have to do that. We paid for this school. Its from our taxes, not from the Hispanics.”

Relations between the children also appear to be cracking. The most telling sign can be found on the buses at Chatham Middle School. The children arrange themselves in neat order. The white kids sit in front, black children in the back and the Mexicans sit in the middle, related Nancy, 11.

Sally Scholle intersects the English-speaking world of Siler City and the Hispanic community. She even has two names, “Sally” in English and “Chelly” in Spanish.

“I’m the person the police call when there’s trouble with a kid,” she said. “The parents call me and the child has to go to the dentist. They call and ask about field trips-they don’t know what those are. Sometimes there is family violence.” Scholle is the only bilingual social worker in the system.

Many children from meat and poultry plant families arrive with terrible past living experiences, little formal schooling, native dialects. Some live in horrible housing conditions, sharing trailers, or live unsupervised in households with multiple families.

“Lead poisoning, rodent bites, pests, fire safety,” Scholle rattles off a list of problems. “We have kids who are depressed and violent.”

Dulce Maria, a mother of four, who lives in one of the more dilapidated trailer parks knows how living conditions affect children. Her middle-school aged son continues to wet the bed and has behavioral problems.

Many families have little experience with formal education and do not emphasize it. They expect their children to work.

“A lot of the older kids work and a lot drop out to work,” Scholle said. “We have had kids who worked the night shift at the poultry plant and come to school the next morning exhausted.”

Many children see their families struggling and want to quit school to go to work. Others despair, knowing that they do not have legal papers and have dim chances for a career.

“My oldest, Juan, says ‘I don’t want to study. I’m going to work, to help you, ‘“ said Maria, who works for Gold Kist Inc., one of two poultry plants in town. When asked where he wants to work, the 11-year-old looks down and says, “Gold Kist, with my Dad and Mom.”

Scholle is going on maternity leave. Her absence will be felt greatly.

“We’ll get another social worker. The question is whether she’ll be bilingual,” said Larry Mabe, the county’s superintendent.

Lee County is seeking two bilingual social workers but the money is tight. There is little hope of getting state funds.

“We’re losing a lot of children,” Higgins said. “It’s increasing our dropout population and our girls are getting married, pregnant.”

The burden of inadequate staffing falls on the ESL teacher.

“Eventually you become a social worker,” said Daniel Gutierrez, an ESL teacher in Morganton where many Guatemalan families have come to work in the poultry plant. In addition to all the other problems, Gutierrez also has to teach children who do not speak Spanish but one of 25 native Guatemalan dialects. “Many of the ESL teachers feel a lot of pressure. The community looks to us for answers.”

No one looks to the poultry plants for answers.

“The fact that the community is making this place for them to bring their families and feel like they want to stay is essentially a subsidy for the chicken company,” Griffith said. Griffith, who studies the poultry industry in North Carolina, believes towns should hold companies responsible and companies should contribute to added costs. But local governments often do not stand up to a large employer. “They just roll over for these guys.”

The new Siler City Elementary school playground was constructed with donated materials and labor from Gold Kist Inc. The effort cost the company $6,000 to $7,000 in labor, according to Randy Johnson, the school’s principal, whose office sports a blue and yellow Gold Kist sign. In February, the company adopted the school where many of its workers’ children attend and permitted workers time off the line to tutor children in reading.

Gold Kist Inc. had annual sales of $1.65 billion in fiscal 1998 and employed more than 16,500 people. The company, which is owned by a cooperative of farmers and based in Atlanta, processes 14 million chickens per week at plants in Alabama, Georgia, Florida, and North and South Carolina.

While helping to build a new playground is beneficial, the school system is trying to raise $8 million for a new elementary school to relieve overcrowding at Siler City Elementary. The county has passed a $1,500 across the board impact fee for any new homebuyer or builder. The fee will hit the immigrant community, which is struggling to buy cheap single-wide mobile homes. The county also has raised taxes.

There is little hope that companies will chip in, said Sandy Tilden, executive director of Chatham Education Foundation. She said the attitude from industry is they pay their industrial tax and that is enough. “I think they do a lot individually with schools,” she said. “It’s not enough. It could certainly be a part of the solution.” She added that Townsends, Inc., the other poultry processing plant, contributes to the foundation and they in turn provided funds for ESL materials to the schools. Townsends contributed $600 this year to the foundation, according to Robert Gibson, the plant’s complex human resources manager.

Some companies have opened their doors to educators, allowing them to conduct surveys and interviews of their immigrant workers to help identify children of migrant families to provide them services.

“We use to just identify kids whose parents were field workers. But just recently we started going down to the poultry plants and the hog processing plants,” said Rachel Crawford, the state’s migrant consultant who oversees the program.

Migrant children whose parents work in the poultry or hog processing industry are eligible for services as long as the parents move within a three-year period to look for more work in agriculture, Crawford said. Local school districts like Chatham have also begun to identify migrant children in poultry plants to fund programs and services using federal assistance.

The state has relied upon the services of the Consortium Arrangement Identification Recruiting or CAIR whose mission is to help states identify migrant education children and provide them services. The organization is funded by some of the largest packers in the business including, Tysons, IBP, Cargill, Excell, Seneca Foods, Agrilinks, Smithfield, and Carolina Turkey. CAIR has helped the state conduct surveys at the Smithfield Company hog packing plant in Tar Heel and a Tysons poultry plant in Wilkesboro. Crawford said the state identified 43 migrant children from Smithfield and more than 100 at Tysons.

Paul Whitley, CAIR’s director, organized a recent meeting in Bladen County to help community leaders address the growing immigrant community and its problems. It was the first time Bladen officials sat down to discuss what was happening in their community.

“This is not going to change,” Whitley, a former Tysons vice president, told the group. “We need to create a situation where newcomers can discover how we live.”

Tysons Foods has sponsored multicultural centers and forums, provided citizenship preparation and life skills training. It is also co-sponsor of an ESL teacher accreditation program in Arkansas.

In a letter to employers, Donald “Buddy” Wray, president and chief operating officer for Tysons, revealed the purpose behind the educational support: “Our need for a better educated and higher skilled workforce continues to grow.”

Tysons’ record sales for fiscal year 1998 were $7.41 billion. Gross profits were $1.15 billion.

The meeting broke new ground for Bladen County. But the schools’ problems have not been solved and even the additional $5 million from the state will mean little to Bladen schools.

Elks knows the challenges for her county are large and permanent. “It’s here to stay. It’s something we’re going to have to deal with.”

©2000 Paul Cuadros

Paul Cuadros is living in rural North Carolina, examining the impact of immigrant meat and poultry workers throughout the South.