Millinocket, Maine–For 85 years, all roads around Millinocket have led to the two Great Northern Paper Company’s pulp and paper mills that sit at the edge of Maine’s huge North Woods. Four generations have enjoyed high-paying, cradle-to-grave jobs. Unrestricted hunting and fishing on the company’s 2.1 million acres have been a bonus for the workers’ isolated existence.

But almost overnight, the guarantee of’ “the good life” has evaporated. Great Northern, the largest papermaker in Maine’s largest industry, has been clobbered by foreign competition and is shrinking in size to survive. High-cost paper machines are being shut down, as production is being cut by one quarter. At least 1,300 of its 3,900 employees, with an average base salary of $25,000 a year, will lose their jobs by 1989, according to current company projections.

The economic shock threatens to unravel the stability of the mill-dependent towns of Millinocket, East Millinocket, and Medway (total population 11,800). Papermaking in a climate of exceptional job security has defined these communities’ entire existence. Like Jung’s archetypal father-provider, Great Northern was expected by the towns to protect the captive workforce in return for its unwavering loyalty.

Charles Roundy, director of the Katahdin Regional Development Council, calls the paper mills’ contraction “the single most adverse economic event to happen to the state in 30 years.” Adds University of Maine political science professor Ed Laverty, a Millinocket native, “People will find that life here won’t be the warm and cuddly ‘family situation’ it has always been.”

The shock to the three towns is a textbook illustration of the impact of the international market on domestic manufacturing. It’s similar to that felt in dying steel, shoe, and textile-dependent towns but is more dramatic here. First, the tri-town area has been such a significant enclave of affluence that its projected decline will have a ripple effect throughout the state; Great Northern has infused $300 million a year into the Maine economy. Secondly, there is no economic diversity around Millinocket to provide comparable job alternatives. Thirdly, being 75 miles north of the nearest city of Bangor, the area’s geography limits its attractiveness to new business investors.

“For the first time in their lives, the people here aren’t going to have the Great White Father [Great Northern Paper] looking out for them and planning their future,” says Wakine Tanous, a prominent local attorney and former state senator. “They are facing all kinds of changes foisted upon them. Most of them, especially the younger people, will have no choice but to move. It’s very scary.”

Great Northern Paper president Robert F. Bartlett has claimed that the company is fighting for its life. He said the new global marketplace has turned most paper markets into “worldwide auctions in which the high-cost mills will not survive.” Great Northern, with a reputation for over-hiring, is rushing to streamline and update itself to salvage its eroding share of the markets for newsprint and uncoated groundwood papers (lower cost printing paper). Partly because of Great Northern Paper’s problems, corporate parent Great Northern Nekoosa’s net income dropped 61.5 percent in 1985, from $119.9 million in 1984 to $46.2 million.

Cost cutting at its different mills, including Great Northern Paper, has helped Nekoosa make a dramatic comeback in recent months, rebounding from a $300,000 loss in the second quarter of 1985 to a $12.4-million profit for the first three months of 1986. Salomon Brothers Inc. paper company analyst Sherman Chao said the paper production cutbacks in Maine will result in a loss in earnings power of about 10 cents per share in 1986 and 1987, but savings from job cutbacks will more than make up for the short-term earnings drop. Over the next several years, Great Northern Paper will realize labor savings of about $36 million per year, which Chao said will amount to nearly 80 cents per share.

The recent earnings improvement has caused some Wall Street analysts to be more favorable toward Nekoosa stock, despite the problems in the Maine operations.

Those 2,600 employees Great Northern says it will keep on the job are facing major changes in work rules that would result in additional savings. The company is demanding contract revisions with the mills’ 14 trades and papermakers’ unions that would give management unprecedented flexibility in making job assignments. They are the kinds of wrenching changes that led to labor strikes against Boise Cascade Corporation’s Rumford, Maine, mill and the Maine Central Railroad this summer.

John Pinette, a 64-year-old second generation papermaker who worked for Great Northern for 46 years, observed that “the whole Great Northern situation boils down to return on investment. They haven’t been getting what they need. If they can’t get it so they can afford to modernize, the mills will be shut down. It’s nothing personal, as I see it, but I don’t think Great Northern Nekoosa honestly cares if Millinocket continues to exist.”

In the last year, the return on investment (on total assets) in the Maine mills was only three to four percent, according to Merrill Lynch analyst Evadna Lynn. For corporate America, the return was 13 percent. Great Northern Nekoosa earned four percent return on equity in 1985, Lynn said, compared to nine percent for the paper industry. Nekoosa, owned primarily by institutional investors, is the eighth largest paper company in the U.S. in terms of capacity. Besides Great Northern Paper, the Nekoosa family includes Great Southern Paper (containerboard), Nekoosa Papers (business papers), and Leaf River Forest Products (bleached kraft pulp). Most recently acquired was J & J Corrugated Box Corporation of Fall River, Massachusetts, the largest independent corrugated box manufacturer in the U.S.

The first wave of job cuts affecting 475 Great Northern Paper workers came this past summer. Cuts are being made on the basis of seniority. A number of the younger papermakers quickly lost their homes and new cars, and moved away. Property values for older “starter homes” and house trailers started dropping and retail trade is slowing. The tax bill for the average homeowner in Millinocket, with 7,500 residents, has already increased to make up for the $191,000 in “lost revenue” resulting from the dismantling of mill machinery and equipment. Widespread “severe hardships” will be felt when the second round of layoffs comes this fall or winter, Katahdin Council director Roundy predicts. “People are living on the hope ‘it won’t be me’ eliminated,” said Arthur Owen, president of Local 37 of the United Papermakers International Union.

As the economic dislocation sets in, local and state officials are searching for answers: What becomes of an area that for a century has been accustomed to the highest standard of living in the state and essentially full employment? Leaders are worried about the future of town services, since Great Northern has paid 70 percent and 80 percent of the taxes raised in Millinocket and East Millinocket respectively. (In tiny Medway, population 1,871, Great Northern pays 22 percent of the taxes.)

“There won’t be a quick fix,” in the opinion of Roundy, whose new office was created to find new businesses willing to locate in the area. “This economy has lived off Great Northern since 1900. Besides having no alternative industries, the towns don’t even have the infrastructure necessary to support business diversity,” he said. “And the people don’t even know how to compete for other kinds of jobs; they’ve never had to develop those job-hunting skills.” It was traditional until several years ago that Great Northern sent in a personnel officer to the high school at each graduation and hired all male seniors on the spot.

Roundy and University of Maine labor economist John Hanson believe that any new employer would probably pay no more than half the starting $11-an-hour average wage at Great Northern. Many paperworkers are earning $30,000 to $40,000 a year (compared to the average $15,400 per capita in Maine), and a lot of them won’t settle for a $5- or $6-an-hour job, Roundy guessed. The area’s unemployment rate is projected to jump from just a few percentage points to a whopping 24 percent by late 1987, he said. Millinocket tax collector Jeanne Bernard said that “everybody has started talking about tightening the town’s belt” on services, but that issue won’t be confronted until early next year when the 1987 budget decisions are made.

Instead of essentially one prosperous middle class, “we’re looking at the creation of a new low-income class here,” Roundy said. “It’s swapping a $30,000 job for 26 weeks of unemployment and food stamps. It will be an alien experience for most.” Attorney Tanous observed the irony in the turn of events, given “the pride” he said Great Northern had in keeping out other industry that would have competed for the paper company’s workforce. Years ago, a shoe factory was interested in locating in Millinocket to capitalize on the female labor available. (At the time, women weren’t allowed to work in the mills.) But Great Northern, which owns all the vacant land in town, reportedly declined to sell or lease property to the business, according to Tanous.

Papermaker Bill Burnette, who believes his job is secure because of his 23 years with Great Northern, said many co-workers are coping badly with the situation. “They’re denying what’s coming.” Real estate agent Joan Carr elaborated, “A lot of people are acting a little like kids. Great Northern had made everyone complacent [about their well-being], and now people are acting like babies being forcibly weaned.”

John DiCentes, president of Machinists Local 156 in Millinocket, believes workers are having trouble adjusting because so many are up in the air about their future. Great Northern won’t say exactly what’s going on and who’s going to be affected. “After the first workers where let go, a number of them were called back to work part-time at $28-an-hour wages and overtime, and it bolstered the hope that everything would return to normal”, Bill Burnette said. Great Northern has declined to be precise about the timing of the next cuts, saying it will depend on evolving economic conditions.

To Great Northern watchers in political circles, the difficulty the workers are having with coping underscores how unusual the company/employee relationship has been. Under the circumstances, it would be expected that the connection would be symbiotic but not like a “family relationship,” according to one high-placed official who is knowledgeable about the company. “It’s bizarre.”

Meanwhile, the company has contracted with a firm to help fired workers cope with “career transition.” But Charles O’Leary, president of the Maine AFL-CIO, said that Great Northern “is playing games” with the workers by not being candid: their best bet for a new job is to move. Also, he doesn’t believe that Great Northern is uncertain about its operating plan for the future. “I can’t believe a corporation as big as Great Northern is unsure where it’s going or what it’s going to do. I think they have made the decision on those job cuts, as well as whether they are going to modernize or sell parts of their empire and make some money.”

A $155 million modernization of two newsprint machines at the East Millinocket mill is currently underway, but updating the antiquated flagship mill at Millinocket is the key to the viability of Great Northern Paper. Without full modernization, the company has said it can’t hold up against its arch competitors–eastern Canada in newsprint and Champion International Corporation and Madison Paper in uncoated papers. But to obtain modernization capital from Nekoosa, Great Northern Paper president Bartlett said it must reduce labor, wood, and energy costs. However, Great Northern has been unwilling to formally commit to modernization in exchange for an agreement with the unions on work rules.

Even if Great Northern doesn’t modernize and the mill closes, Millinocket townspeople believe some other company would buy it and run it, given the enormous resources of plant, timberland, and the largest industrial hydropower facilities in the Northeast. “This place won’t end up like a ghost town,” attorney Tanous said. “I think the population will drop down by half, to the level it was when I came here in the 1950s.”

Union leaders believe that if Nekoosa continues to own the mills, eventually they will run only two state-of-the-art paper machines in each plant, compared to the 11 largely outdated machines operating now. According to after-hours pub chatter, just having four machines would require a lot more job cuts that the 40 percent reduction Great Northern has announced. There are modern paper machines that require only two workers per shift to operate, compared to the five per shift currently working on Great Northern machines.

Some people say they saw the writing on the wall three years ago, when the company stopped hiring high school seniors for summer jobs that paid $4,000 to $5,000. “The common talk on the street was that things didn’t look good for the Northern,” said Bill Burnette. Workers blamed the downturn on the 1970 merger of Great Northern with the Nekoosa-Edwards Paper Company. They believe the parent corporation began siphoning off profits from the highly productive but aging Maine operations for new expansions in the South, generally perceived by the industry as a better investment location because trees there have a longer growing season, labor is cheaper, and unions are not as entrenched. “Company headquarters moved from Millinocket to Stamford, Connecticut, talk centered around the big corporation and the board room, and workers began to feel they were at the mercy of someone else who could write them off as a loss,” said AFL-CIO leader O’Leary.

Workers’ fears were realized when president Bartlett announced on January 31, 1985, that the company was in financial jeopardy. Besides the job cuts, he said that the unions would have to compromise away many of their hard-won work rules that Bartlett characterized as costly and archaic. He said Great Northern must, like competitors, move to greater labor efficiencies through multi-craft, team concepts and flexible work assignments to reduce the labor costs of producing paper. Bartlett said Great Northern’s man-hours per ton was 5.8 in 1985, compared to 5 for Quebec, 4 for the U.S. South, and 3.7 for Finland. “With salaries and wages comprising 40 percent of all our costs, there is no way we can survive unless we address this problem,” he said.

To the unions, who have one of the oldest contractual relationships with management in the country (pre-National Labor Relations Act), it smacked of a sell-out of almost 85 years of “good faith collective bargaining,” according to Dale Hartford, chairman of the Trades Negotiation Committee and a district representative of the Machinists’ Union. The unions saw the company’s move as a power grab by management, especially because of its refusal to accept the union proposal to tie worker concessions to modernizing the Millinocket mill.

Ed Laverty is critical of the weekly Katahdin Times’ failure to inform the communities that “what is good for the company is not necessarily good for the community. The paper has always followed the party line.” With the unions’ unusual complacency and their hand-in-glove relationship with the company, a questioning voice would have been a “tremendous service to the people who needed to understand the differing interests,” Laverty said. “Frankly, we really haven’t had a free press in Millinocket. It’s been as captive as the workforce.”

Although the newspaper is now writing articles on the impact of the job cuts and encouraging readers to share (even anonymously) their stories of life after Great Northern, the Times hasn’t explored the issues underlying the company’s restructuring. Townspeople’s questions of “how did this happen to us” are left to speculation at coffee shops and bars.

At Jo and Mary’s Restaurant or the Heritage Motel bar in Millinocket, it’s commonplace to hear arguments over who’s to blame. Some workers can see that the unions had a strong role in featherbedding at the mills and fostering the illusion that there would always be jobs for everyone. But most blame Great Northern management for not forcing streamlining and updating the plants, as other company leaders were doing years ago in response to increased competition. “I think there’s been a lot of mismanagement,” said trades union leader Dicentes. “I’ve worked for the company for 27 years, and I’ve seen management capability erode. It has never been as bad as it has been in the last two years, from line foreman to the top.”

In the early 1960s, when times were good, “you started seeing all these new jobs created, and that’s the way it’s gone ever since,” said attorney Tanous. The company “hired more and more people, making room for anyone in a family. Girls wanted jobs, and they found something for them. But anyone living here knew the company had no new machines. It was just that paternalistic pattern established years ago. The unions pushed it, enjoyed the prestige of getting more people hired. Neither the unions or management seemed to grasp the fact that there were going to be big bills to pay in the good and bad years. You take 15 to 20 years of concessions [to labor], and it’s too much. The balloon had to burst at some time. The profit picture couldn’t take that.”

Great Northern not only got squeezed by spiraling labor costs but a drop in product prices due to an oversupply of paper, and a new market emphasis on quality, not quantity. The company found itself too big and inefficient in an industry headed the other way toward leanness and modernization. Complicating the company’s situation in the 1970s was the massive infestation of spruce budworm disease that attacked the spruce and fir trees used to make paper. Before the announced cutbacks, Great Northern was facing a projected shortfall of 300,000 cords of wood, according to woodlands manager Bart Harvey. But the planned 200,000-ton reduction in capacity down to 647,000 tons in 1987 may erase the negative effect a timber shortage could have.

In 1901, Millinocket was carved out of a wilderness as wild as the old West. Its avenues of development were laid out grid style, four miles by four miles, and the speed at which the town was built caused it to be dubbed “The Magic City.” Although today it is on the fringe of a commercialized forest, and not a wilderness, Millinocket still retains the flavor of isolationism and spirit of a frontier town far from the mainstream of life. Until recently, Joan Carr was fond of saying, “Anything the rest of the world has, give Millinocket 10 years.” Now, she says, “I think it’s three.” The town is so isolated that Carr said people’s “idea of fun is McDonald’s on a rainy Sunday morning.”

What is so striking about Millinocket is the absence of architectural attractiveness. Strict utilitarianism is the rule, and while it may not be a pretty town, it is well kept. There are no housing slums, thanks to Great Northern’s role as the de facto zoning board.

The mill stacks towering over Millinocket and East Millinocket are symbols of the dominance of Great Northern Paper. The sprawling plant complexes cover dozens and dozens of acres, and the company owns virtually all of the undeveloped land for miles around. The mills consume 1.1 million cords of wood per year, half cut from Great Northern’s lands and half from woodlots of independent owners.

Company founder Garrett Schenck wanted Millinocket to avoid the seedy rowhouse construction of textile towns, so he insisted that the company retain control of new home building, therefore obviating the town’s need for local zoning. Great Northern sold land to workers for a couple hundred dollars, approved building plans down to the size of lawns and length of driveways and lent bulldozers and graders to prepare sites.

While the town has no frills, such as downtown landscaping, the people have spent lavishly on themselves. The well-paid Great Northern workers are known throughout the state for the number of “toys” in their backyards–snowmobiles, trucks, cars, boats, motors, canoes, and campers. They enjoy color televisions, VCRs, microwave ovens, shopping sprees to Bangor, summer lake cottages, and vacations to foreign places. Easy credit has always been available from the four banks in Millinocket, although that is apparently changing. One missed mortgage payment now generates a phone call from the bank.

The new financial realities have caused a number of people to put their houses on the market. The “for sale” signs are the most visible marks of the area’s dismal economic prospects. Joan Carr, a real estate agent, said she and her husband, Lawrence, manager of the Millinocket Foundry, have borne the brunt of criticism by friends and neighbors because they put their home and summer cottage on the market shortly after the jobs cutbacks notice.

Because the Carrs acted as if they were scared, “people got mad at us,” she said. “They didn’t want us to let the cat out of the bag [to outsiders] that things are really bad.” She pointed out that people have put most of their earnings in their homes and other personal property, and are afraid they won’t be able to sell and get out.

Stuck in the Woods

Like some of their neighbors have already done, the Carrs are planning to move to the more populous southern Maine coast, now undergoing an economic boom and soaring real estate values. In fact, going to a starkly different situation is exciting just to consider, she said, given the years of “being stuck in the woods.” But for Carr, it won’t be an easy exodus from the place she grew up. “It’s been a good life.” Four generations of her family have worked in the mills, and all have lived in proximity to each other. “There has been a real closeness,” she said, “and a son in the Army in the Mediterranean cried when he heard we were selling. He ‘Mom, is our family falling apart? Is the town falling apart?’ “

When the Millinocket facility was built in 1898-1899, it was the world’s largest paper mill. Great Northern chose the site because of the timber base and water power. It was able to purchase 2.1 million acres (10 percent of the state) for $2.70 to $13.70 an acre, and in time it built six hydro and 13 storage dams on the Penobscot River capable of generating 80,000 kilowatts of electricity.

For 70 years, Great Northern drove logs down the Penobscot to the mill at Millinocket, and then to the plant built a few miles down the road in East Millinocket in 1907. The river drives stopped in 1971, and Great Northern built 3,000 miles of roads into the forest to haul the wood to the mills.

The recreational opportunity for fishing, hunting, and canoeing on company lands was valued highly because of the hard, often dangerous, working conditions at the mills. Some of the most physically demanding jobs led to the loss of life, limb, hearing, and complaints of illnesses, ranging from asthma to cancer. Before air quality laws clamped down on mill pollution, sulfur dioxide emissions were so strong they caused paint to peel off houses downwind of the mills.

Papermakers organized a papermakers local 27 union in 1901; it was one of the first in the nation. In its first year, the union won an eight-hour day for its members–a first in American industry. Thirty nine years later, they got one-week paid vacations, another industry first. Then a few years later, fringe benefits were added to worker’s compensation. Samuel Gompers’ one-word definition of organized labor’s aims–”More”–became the watchword, and the company continued to give the unions much of what they wanted, as long as profits were high. It was the same strategy that auto, steel, and railroad companies followed when times were good.

It wasn’t until 1978 that the mill was shut down by a modern-day strike over wages and benefits. It bruised the “family relationship” for awhile, but with the strike over in days, the close-knit relationship seemed restored. Today, union leader Dicentes said the “working hand in hand” is definitely over, that the “family feeling” is gone. “The men up here feel like they are just a number, and the company just wants to use you up and let you go.”

Although much of the recent focus has been the union’s response to the proposed work rules changes and extension of current contracts from 1987 to 1990, the bottom line worry is modernization of the Millinocket mill. “We have no indication of what the future is,” said DiCentes.

Retired worker John Pinette said the big mill is “in terrible, terrible shape and is falling down.” He says it would take $500 million to make it state-of-the-art but others have guessed it would take $250 million. Nekoosa said firmly that unless Great Northern Paper can become more efficient, it will not get the improvement capital it needs, according to company public affairs spokesman Gordon Manuel.

There is some suspicion among workers that the desperateness with which Great Northern presents the modernization issue is an attempt “to jerk us around” over the contract, according to papermaker Bill Burnette. The trade unions initially rejected Great Northern’s proposal to change the work rules, take away Sunday and holiday time off, remove the prohibition against using non-union subcontractors, and extend the current labor agreement through July 31, 1990. But they fell in line and approved the revised contract, following acceptance by the papermakers union.

There’s a feeling among some Great Northern workers that the strength of their union locals will never be the same again, especially in light of the new trend for management to replace recalcitrant employees. During the 10-week strike at Boise Cascade, 342 production workers were substituted with men and women off the street attracted by the high-paying wages.

Boise’s hard line is not lost on the unions at Great Northern. They view what happened at Boise as “setting the tone” for the other major mills in Maine–International Paper, Champion International, Georgia-Pacific, and Scott Paper. Given what went on at Boise, “we’ll have to play hard ball again next year,” said union leader O’Leary. “It will be awful, and I think there’s danger in some of these [paper mill] communities.”

But John Pinette said that management’s demands are “the modern way.…Boise put it to the test. [Great Northern] can afford to beat the unions. “Living the way they have on credit,” they are helpless to fight back. They owe their soul to ‘the company store.’ “

©1987 Phyllis Austin

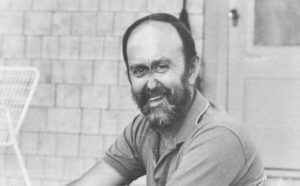

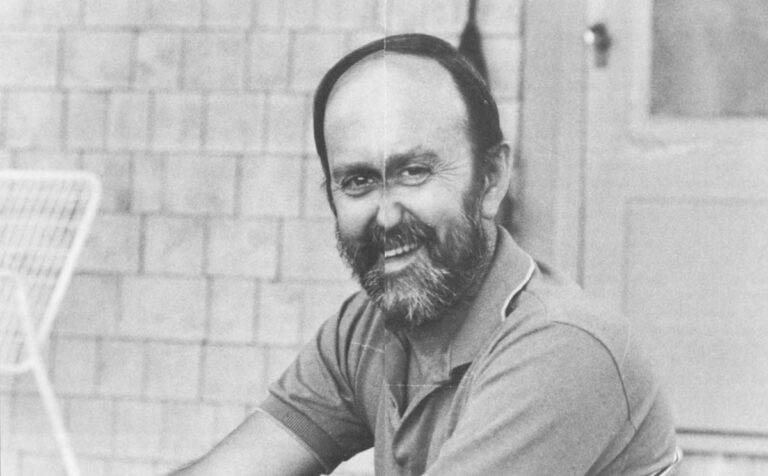

Phyllis Austin, a reporter on leave from the Maine Times, is investigating how the pulp and paper industry has fostered the crisis in the Maine woods.